Related

Topics

Guests

- Ian Millhisersenior fellow at the Center for American Progress Action Fund and the editor of ThinkProgress Justice. His latest piece is headlined “The Simply Breathtaking Consequences of Justice Scalia’s Death.” He is the author of the book Injustices: The Supreme Court’s History of Comforting the Comfortable and Afflicting the Afflicted.

- Linda Hirshmanlawyer and historian. She’s the author of Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World.

- Scott Hortonhuman rights attorney and contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine. He is also a lecturer at Columbia Law School.

Nearly 30 years ago, Antonin Scalia was approved by the Senate in a unanimous vote. Analysts are projecting a much tougher road for the next nominee. We look at four potential nominees: California Attorney General Kamala Harris, D.C. Circuit Judge Sri Srinivasan, Ninth Circuit Judge Paul Watford and Eighth Circuit Judge Jane Kelly.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Scott Horton, what about this issue of the—what happens from here on in, and also the choices that President Obama has? Does he name a more moderate justice and then really make it difficult for the Republicans to continue to block a nomination, or does he attempt to go to a more liberal justice and really sharpen, in the upcoming election, the choices that voters have when they’re electing a president?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, you know, to me, the political elements here have never been sharper for the Supreme Court. So I think we’re going to see this whole issue of the Supreme Court front and center in the election campaign for the new president. It’s always there in the final rounds of the election; we usually have candidate saying, “Who is selected now as president will determine the makeup of the Supreme Court.” And now we’re in the position where that literally is going to be true. So it will be central.

As for Obama’s options, it seems to me he’s going to be—he’s going to play a tactical game at this point, knowing what the position is of the Republican majority and their leader. And it seems to me the Republicans have put themselves in a position in which they’re going to be subject to ridicule based on their own conduct. I think it’s likely that Obama will put forward a nomination of a moderate with outstanding credentials, and probably someone who has recently been approved by the same Republican Senate by a strong vote, and watch them cope with that, because I think if their—if their tactic is simply to block, that’s not going to help them in the presidential election.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what would be some of those—who would be some of those potential folks that he might name?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, Sri Srinivasan, I think, is the most commonly cited figure right now, but I think we’ve got a group, principally, of court of appeals judges who were approved over his two terms as president, who have gotten substantial support, including support from Republicans. There are a half-dozen of them in the holding pen right now. Any of them may be put forward. But I doubt it’s going to be the left equivalent of a Nino Scalia. It’s going to be someone who is more of a moderate, more of a centrist, someone who in normal times would be able to count on Republican support.

AMY GOODMAN: Ian Millhiser, can you talk more about Sri Srinivasan, who he is and his significance?

IAN MILLHISER: Sure. I mean, Sri is—I’ve seen him argue cases before. He’s one of the most brilliant litigators of his generation, truly breathtaking intellect. He also, though, clerked for two Republican judges—for a Republican court of appeals judge and then for Sandra Day O’Connor on the Supreme Court. He spent many years of his careers at a major corporate law firm. So he’s very much perceived as a sort of middle-of-the-road moderate, the sort of candidate a Democrat would put up if they wanted to extend an olive branch and say, “Look, like, I’m going to meet you halfway here by picking someone who wouldn’t necessarily be a Democrat’s first choice, but someone who everyone agrees is an extraordinary intellect,” someone who was confirmed 97 to zero the first—when he was confirmed to his current job on the second-highest court on the land. And so I think Sri is going to be attractive to the White House.

There’s a—you know, there are some other candidates—Paul Watford on the Ninth Circuit—

AMY GOODMAN: Just on Sri Srinivasan, he would be the first Indian American. He’s young, he’s 48 years old.

IAN MILLHISER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Labor unions were not thrilled when he went up to this court, not feeling that his history of representing corporate clients would bode well for them.

IAN MILLHISER: Yeah, that’s right. I mean, what you’re looking at with Sri—and, you know, again, the fact that he had certain kinds of clients as a lawyer doesn’t necessarily predict how he’s going to act as a judge or a justice. But everything we know about him now tells us brilliance and centrism.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about Paul Watford?

IAN MILLHISER: Sure. Judge Watford is a judge on the Ninth Circuit. He has a similar résumé to Sri. He worked at a corporate law firm for many years. Unlike Sri, Judge Watford is—was a clerk for Justice Ginsburg. So he has a similar profile of someone who’s been at the top of the profession since the beginning of his career, a great intellect, someone who shouldn’t be perceived as a bomb thrower and should be perceived as more of an olive branch, because he spent most of his career not doing anything that’s really associated with liberalism, just, you know, going out there and making money as a lawyer. So, you know, if it’s Watford, if it’s Srinivasan, if it’s either of those judges, under normal circumstances, that would be an olive branch to the Republicans.

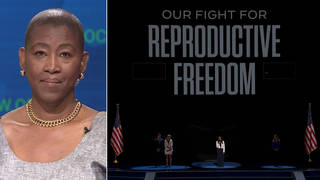

AMY GOODMAN: And, Linda Hirshman, can you talk about Kamala Harris, attorney general of California, running for Senate—

LINDA HIRSHMAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —to fill Barbara Boxer’s seat?

LINDA HIRSHMAN: Right. She would be my selection, if she’s—you know, if she passes the vetting process, because I would just love to see the next several months occupied with a bunch of old white male Republicans pounding on the first Asian-American, African-American attorney—female attorney general of the state of California.

But I think that it’s mostly about the optics. As I listen to my colleagues just now discussing the pros and cons of the olive branch possibilities and so forth, I think that none of this really matters at all, because the Republicans, as far as I’ve been able to observe, do not care about the universe of perfect logic. And the fact that Srinivasan was confirmed 97 to nothing just recently is an argument which reasonable people would make, but I don’t think it matters. I think that this is about power and optics. And if you are going to be realistic about what’s going to happen, then you have to think about who would make the most optically advantageous appointment. And I think Kamala Harris would be very high on my list of people who would do that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Another—

LINDA HIRSHMAN: That being said—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’m sorry. Another person who’s been mentioned is Jane Kelly from the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. Could you talk about her?

LINDA HIRSHMAN: I would be—I would be inclined more in the direction of an African-American woman like Kamala Harris. I don’t—I don’t think that it’s about the woman thing right now.

AMY GOODMAN: Because?

LINDA HIRSHMAN: Because I think that getting African Americans to go to the polls in sufficient numbers to elect a Democrat president of the United States is the critical political issue right now. Obama’s numbers from 2008 to 2012 went down among Hispanics and whites. And only a robust African-American vote was effective in 2012. So I’m thinking politically about this. The Republicans are looking at their red states. Arizona, for example, where I live in the winter, will be in the very liberal Ninth Circuit. They’re looking at their constituents living under the governance of very liberal blue circuits. And they are looking at a—I want them to look at the most attractive, politically attractive, possible nominee.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to ask Scott Horton, with the current split in the court—we’ve got all these big cases coming up this term, have to be decided by June—what is your sense of what the fallout will be on some of these cases, if any, that the court may go ahead with?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, I think labor unions can breathe a huge sigh of relief right now, because they were probably looking at a really powerful adverse ruling on the union dues issue coming in one major case. And one fundamental rule here is, it doesn’t matter how the justices voted in conference or the discussions that went on; the vote that’s taken has got to be the vote as it existed at the time the ruling is handed down. So, nothing that’s happened up to this point matters. We’re dealing with an eight-member court on all of these rulings.

But I think, coming back to what was—what Ian said at the beginning, we’re looking at a court that is likely simply to uphold the rulings below. So, in cases where—as in the immigration rights case and the voting rights cases coming out of Texas, where there is a conservative ruling from a conservative court of appeals, that’s likely to be sustained still, I think, and where it was a more progressive ruling, that will be upheld.

AMY GOODMAN: Ian Millhiser, before we go to break, if you could talk about what Justice Scalia is known for, whether we’re talking about his support for gun rights, his opposition to same-sex marriage and LGBTQ rights, whether we’re talking about abortion, talk about his history, this history of—

IAN MILLHISER: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: —a man who was appointed by Ronald Reagan.

IAN MILLHISER: Sure. I mean, I think that Justice Scalia is a very tragic figure. I mean, if you read a lot of his scholarship, he would articulate a theory of judicial restraint that I think is admirable, this notion that we should be cautious about courts getting too involved in our lives and that we are a democracy and democracy should rule. As a scholar, I think he made very interesting arguments. But as a judge, he often lacked the character or the self-control to live up to the arguments he made as a scholar.

So, you know, the two most—the two most striking examples of this are the two Obamacare cases, where in the first one he wrote a—or he joined a vicious dissent to his own opinion in another case called Raich, and then, in the second one, he attacked his own theory of judicial—of statutory interpretation that he laid out in a 2012 book. So, he was a great scholar. I think—I wish that he’d been able to live up to his own ideals. But unfortunately, all too often, I think he let ideology and partisanship get in the way of some of the more idealistic notions that he articulated as a scholar.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Scott, I’d like to ask you about the irony of Scalia being a proponent of originalism, of faithfulness to the letter of the Constitution, and yet now the Republican majority saying, well, the president should not really exercise the powers that the Constitution gives him to name the next Supreme Court justice.

SCOTT HORTON: Well, I think it is highly ironic. I mean, you know, this was a politically driven conservatism. And I think Scalia’s conservatism is unlike what we’ve seen through most of American history. He’s sort of a southern European throne-and-altar type of conservative and not the sort of more progressive conservative that embraces some liberal values we’ve seen through most of American history. And he came up with a formula that would sustain that, which was to try and freeze the country in time constitutionally at 1789, which was a framework that gave him more ballast for his arguments, but certainly didn’t help him win every case.

But I think, you know, his zeal—he undermined himself with his own zeal over and over again, you know, especially in the last few years. He would attack the majority on case after case, saying X, Y, Z is consequence of their opinion, and you’ll see—and, of course, that comment was then used by district courts to sustain a more radical interpretation of the majority’s opinion, and that hastened things along, like marriage equality.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, then come back to this discussion. I want to thank Ian Millhiser for joining us, editor of ThinkProgress Justice, author of Injustices. Linda Hirshman is staying with us, author of Sisters in Law, a very interesting book about Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg; the subtitle, How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World. And we’re joined by Scott Horton, human rights attorney and lecturer at Columbia Law School. Kimberlé Crenshaw will now be joining us, as well, from UCLA in California. This is Democracy Now! We’re talking about the death of Justice Scalia and what happens next. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: With Saturday’s death of Justice Antonin Scalia, the most important conservative voice on the court in decades, the nation may be heading into a constitutional crisis, Senate Republicans vowing to block President Obama from filling Justice Scalia’s seat. We’re joined by three guests. Linda Hirshman is still with us from Phoenix, Arizona, lawyer and historian, author of Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World. We’re joined here in New York by Scott Horton, human rights attorney and contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine, a lecturer at Columbia Law School. In a moment, we’ll be joined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, professor of law at UCLA and Columbia University. We’re going to turn, though, to Scott Horton.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Scott, I wanted to ask you about Scalia’s last decision, which was on a clean power case last Tuesday. He was the decisive vote on that, as well. Could you talk about that?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, I think it’s clear right now that that injunction that was issued by the Supreme Court would not have been—wouldn’t be issued today. His vote was essential to get it over the hump. And that was a radical move. There is really no precedent for the Supreme Court issuing an injunction staying pending argument in the Supreme Court regulations of general applicability of this sort.

AMY GOODMAN: But just to be clear, this was—struck down regulations of coal-powered plants, which was really the centerpiece of what—on the U.S. position at the U.N. climate summit in Paris.

SCOTT HORTON: Precisely. And, in fact, I think this decision got more attention overseas than it got in the United States, because we saw a number of European nations focused on the fact that it looked like the Supreme Court was going to block United States’ implementation of the Paris Accords, because these regulations were right at the core of it. And now there clearly is not the majority within the Supreme Court in support of that injunction. But we’re going to have to see—either there will have to be a motion for rehearing of the matter by the solicitor general, or we’ll have to await the final decision. But it’s no longer as clear that the situation is ominous for Barack Obama on these regulations.

Media Options