Related

Guests

- René Pérezco-founder of the Puerto Rican band, Calle 13. He is better known as “Residente.” The group has won 19 Latin Grammy Awards — a record — and have also won two Grammy Awards.

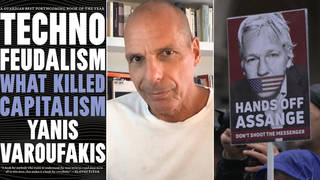

Calle 13, one of Latin America’s most popular bands, released a new song this week featuring an unlikely collaborator — WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. The song, “Multi_Viral,” also features Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine and the Palestinian singer Kamilya Jubran. To create the lyrics, Calle 13 lead singer and songwriter René Pérez asked followers on Twitter to express their social justice concerns in a live brainstorming session with Assange. This is not the first time Calle 13 has made headlines for its political work. In 2005, the group quickly recorded and released a song about Puerto Rican independence leader Filiberto Ojeda Ríos just hours after he was shot dead by the FBI. They have called for the release of independence activist Oscar López Rivera, who has spent more than 32 years in jail, and have spoken out about police brutality and government spying. We speak with Pérez, better known as “Residente.” His group has won a record 19 Latin Grammy Awards.

Haz click aqui para ver la entrevista en español (Watch the interview in Spanish).

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: One of Puerto Rico’s popular bands is out with a new song this week with an unlikely collaborator. On Wednesday, the band Calle 13 released their latest tune titled “Multi_Viral.” It features the voice of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

CALLE 13: Crece la ola, crece la espuma, cuando cada vez más gente se suma.

JULIAN ASSANGE: We live in the world that your propaganda made. Where you think you are strong, you are weak. Your lies tell us the truth we will use against you. Your secrecy shows us where we will strike. Your weapons reveal your fears for all to see. From Cairo to Quito, a new order is forming: the power of people armed with the truth.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: An excerpt from Calle 13’s new song “Multi_Viral,” or “Multi_Viral.” The song features Julian Assange, as well as Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine and the Palestinian singer Kamilya Jubran.

In recent years, Calle 13 has become one of the most popular acts in Latin America. The band has won a record 19 [Latin] Grammy Awards, as well as two Grammys.

AMY GOODMAN: So, 19 Latin Grammys, two overall Grammys. This is not the first time the band has tackled a pressing political issue. In 2005, Calle 13 made headlines when it quickly recorded and released a song about the Puerto Rican independence leader Filiberto Ojeda Ríos just after hours that he was shot dead by the FBI. More recently, the band called for the release of independence activist Oscar López Rivera, who has spent over 32 years in jail. The band has also been vocal about police brutality and government spying.

Joining us now, René Pérez, better known as Residente. He is the lead singer and songwriter of Calle 13.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

RENÉ PÉREZ: Thank you. Hi.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s great to have you with us. You’re here in New York recording a new album?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, I’m recording a new album with my brother. And I just got here. It’s super cold for me. But it’s nice. You know, I’m still writing and doing these kind of songs. And we make fusion. You know, our music is like, this song is going to be different from all the other songs, but we talk about different situations, the things that surround us—you know, political things, religion, sexual things, party, everything, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the making of “Multi_Viral,” “Multi_Viral,” with Julian Assange. How did this happen?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Well, it was a little bit difficult to get there at first. And—but at the end, we did it, and I met him, and he was a very cool guy, you know, like a nice guy. You know, because before I met him, I read the press, and they were saying that he was like arrogant or—I don’t know, but he was a nice guy. And he was very open to work with us. So we started working at the embassy, asking the people to—you know, asking questions to the people. And we started using those answers to write the song. At the end, I gave them like an email, and they sent us like words. And I used those words as a puzzle to construct the song. So, it’s like—you know, at the end, it’s like the voices of the people, you know, the lyrics. So that’s why the song also is for free, you know, because it’s for the people, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, from—you’ve had a—really, an amazing rise in terms of—your group—in popularity in a very short time. But you began from the very beginning with very political songs. Talk a little bit about why you felt the need to have so much politics in your lyrics.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Well, it’s pretty easy to—you know, I’m surrounded by politics. First of all, I come from Puerto Rico, and we are a colony of the U.S., so it’s easy to be into politics. Like, we are right away into politics because we’re a colony. So, yeah, our first song was called “Querido F.B.I.,” “Dear F.B.I.,” and it’s about the killing of Filiberto Ojeda Ríos. You know, I thought it was so wrong and unjust, and I just wrote it. But the key for our group and this tragedy was we mix like—we did “Atrévete,” that it’s like a fun song, and then we did, “Querido F.B.I.” So it’s—we have a balance. That way the people doesn’t put us in a—in a place, or all this—this all the time is about politics and—you know? So that way we can balance the whole thing, and people who doesn’t listen to social songs, they are into that, you know?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you call yourself “Residente,” and your brother, “Visitante.” Could you talk about how those titles—how you came to adopt those titles, and, for people who don’t know what life is like in Puerto Rico, how that arose?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, well, at first it started out as a joke. We were joking, and we didn’t thought that Calle 13 was going to be big. And that’s—you know, we used to live in the Calle 13, is Street 13, 13th Street. And every time that we wanted to go inside the neighborhood, we had to say our names, like “Residente Calle 13” or “Visitante Calle 13.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And that’s because, because of the crime level—

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —there’s so many gated communities in Puerto Rico, basically, with security guards, you have to be let in and out, right?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, they were robbing and assaulting a lot at that time. So, yeah, we had to say our names like—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: So you were the “Residente.”

RENÉ PÉREZ: Residente.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And he was the visitor, the “Visitante.”

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, because he used to—like, he’s my brother, but he—we are like from divorced families, so he used to come and visit every weekend. So, that’s why he’s the “Visitante.”

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to Filiberto Ojeda Ríos, the leading figure for the fight for Puerto Rican independence and against U.S. colonial rule, wanted by the FBI for his role in a 1983 bank heist. And in 2005 in Puerto Rico, he was killed by the FBI in a shooting, after agents surrounded the house where he was staying. According to the autopsy, Filiberto Ojeda Ríos bled to death after being hit with a single bullet. Officials didn’t enter his home until many hours after he was shot. He was 72 years old. He had founded the Armed Revolutionary Independence Movement, later a key organizer in the FALN, the Armed Forces for National Liberation. Can you talk about why that inspired you so much? This was really your breakout song. You had just cut a first album, right? And then you just put this online.

RENÉ PÉREZ: You’re talking about “Dear F.B.I.” or—

AMY GOODMAN: “Dear F.B.I.”

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah. Well, at that time, I was sad of the whole thing. And because also the day they—the day that the FBI chose to kill Filberto was the only day that we celebrate as our freedom, because we were free for eight hours, believe it or not, so we celebrate that. You know, some people celebrate that. So, they killed him that exact day, you know? And it was—I thought it was they were sending a message, you know: This is your eight hours’ freedom day, so we’re going to kill him in that day. And he’s going to die. And he died.

And nobody—over there, like a few people—like a few people cared. But the majority of the people, they thought, no, great, they kill a terrorist, or whatever. And that’s why, like, I was so mad. So I—and that same day, I wrote the song, and I just put it over the Internet, the same way I did “Multi_Viral.” And it was very difficult, because, you know, we did “Atrévete,” and we had—we were like right—we were going to sign a contract with an independent label at that time, and they got scared, you know, because nobody talks about it over there. Like, if you talk about the independence of Puerto Rico, you know, you’re just part of the 5 percent of the people, so you’re going to have like the 95 percent against you. But it was different, like the people liked it. In a way, it was the first time that in the barrio — I don’t know how you say that. You—yeah?

AMY GOODMAN: In the neighborhoods.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In the barrio.

RENÉ PÉREZ: In the neighborhoods. Yeah, but, you know, they started listening to those kind of songs. It was the first time that that happened. And I was—and I was happy about it, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You released it through Puerto Rico Indymedia?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In terms of the—we were just talking in the prior segment about the ACLU report on the brutality of the Puerto Rico police force. That’s also been a theme of your—of some of your songs. Could you talk about the police in Puerto Rico and the relationships with most, especially the poor, communities?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, well, you have good cops, you have—you have bad cops, you know, like everywhere. I have some friends, they are cops. And some of them, they are not cops. So I wrote a song about the police brutality also because I—one of my best friends got killed because of the police. They hit him 'til death, ’til he died. So, I wrote a song, and we started giving the song for free also in front of the police station, the most important one. We didn't want it to cause trouble; we just wanted to make people aware of what is happening over there. And it was nice also to do it. Like, I’m just doing the things that every artist can do and should do, I think, you know. These topics, the social topics, they are not the only topics that we talk about. But what we talk about it, it’s like in painting, you know, when every movement, they talk about the politics and war and everything.

AMY GOODMAN: According to news reports, documents provided by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden show that both the NSA and the CIA maintained a joint operation from the U.S. Navy’s old Sabana Seca base in Puerto Rico in a suburb of San Juan. The operation there worked to intercept satellite communications with other NSA teams in Brasília, in Bogotá, in Caracas, in Mexico City and Panama City. You’ve gotten very involved in this issue. In fact, you just tweeted out that you’d like to get a celebrity to donate a jet; you’d go pick up Edward Snowden and bring him to Latin America for asylum. Why is this so important to you? And what about Puerto Rico being used as a base for spying?

RENÉ PÉREZ: I feel ashamed as a Puerto Rican. I don’t want that to happen. They did it also with the president of Venezuela while he was flying over—he wanted to fly over Puerto Rico, and they didn’t give him permission. And they did it with also—

AMY GOODMAN: President Morales of Bolivia.

RENÉ PÉREZ: President Morales, yeah, and he couldn’t land. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Well, they forced him to land because they thought that he had Edward Snowden—

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, that he had Snowden. So that’s—

AMY GOODMAN: —coming from a Russia OPEC meeting.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, and so that’s why I came up with that tweet, because if—you know, if I had the opportunity to help them, I help him, you know? And I think it’s very important what he’s doing. Like for me, I’m a normal guy, like I don’t—I don’t have all the information of everything about everything, but I know a few. And with only knowing this few, I just want things to change. And I think that if we can do that in the whole Latin America, and I can translate what is happening with my songs from English to Spanish, you’re going to have like a lot of—he’s going to have a lot of supporters, you know?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Speaking of Latin America, you’ve increasingly been touring there, and your songs have been gathering followings there. Could you talk about the impact of the social movements in Latin America on your work and what you’re hearing when you go and play before audiences there?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Well, Latin America is a very busy continent in terms of movements and militants. That’s the way you say? Militants? Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Militantes.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Sorry about my English. Yeah, militantes, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Sí.

RENÉ PÉREZ: I speak way better in Spanish. So, you have like—you have a huge movement of student—student movements. Like, for example, you have in Chile a real huge movement, like in 2011, when did you have like Giorgio Jackson and Camila Vallejo. Like, they are like—they were like on top of the student movement. And it became viral, because then you had it in Colombia against the 30 law. And then you had it in—in Argentina, you always have that because there is a lot of movements there with students. And then it became viral. And, you know, Latin America is—right now is developing so fast that I’m—you know, I feel great.

AMY GOODMAN: René, you—your band, Calle 13, has won more Latin Grammys than any band, than any musical group—19—and also won two Grammys. Do you face pressure not to be political because you are so successful in the commercial world?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Sometimes, I just—but I just do whatever I feel. If I feel that something is wrong and I should talk about it, or if I feel about saying something, I just say it, you know? And some people—sometimes I feel a little bit of pressure, because the people come to me, and they start like—they send a lot of emails, like, “Talk about this issue, and talk about this issue.” And it’s like millions of emails, you know, at the end. But I—you know, I don’t feel that pressure, you know, and we maintain a good balance. We did this with Tom Morello, and we did a song with Shakira. So, it’s like—that’s the way to reach Shakira’s kind of fans, you know.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, and you’ve gotten so popular that a few years back, the pro-colonial or pro-commonwealth governor, Acevedo Vilá, invited you to play at the Fortaleza, because he said his children listen to your music all the time.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah, that was like way before we got censored in Puerto Rico for four years. We couldn’t perform over there, because of ex-Governor Fortuño and—well, not the governor, but the mayor of the city of San Juan. We couldn’t perform in San Juan, that is the major scene.

AMY GOODMAN: Because?

RENÉ PÉREZ: Because I said a few things in the MTV awards. I said pretty bad words to him. But also, I wanted to keep the attention of a huge strike for the workers, you know? Because he asked the people to vote for him, and he wasn’t going to fire anyone, and at the end he fired like 60,000 people. So I just—I just felt that way. And I was on the MTV, so I said it. And they censored me for four years. And now, like last year, we performed there, and it was great.

AMY GOODMAN: In the most recent song that you just put out with Julian Assange and Tom Morello, you have Spanish, you have English, you have Arabic. Talk about blending these languages.

RENÉ PÉREZ: It was fun. At first, I didn’t know, like, how I was going to do it. At the end, I started making a huge research of who can help us in the chorus, because I didn’t want to have it all in Spanish. And I thought about—I start making a research, and that way I found about Kamilya Jubran, that she’s from Israel, but her parents are from Palestine. So I thought it was a great mix. And I heard her voice, and she was amazing, so I contacted her, and I asked her, and she wanted to do it. And I put like a little bit of French, pas à pas and coude-à-coude. So, yeah, I just was trying—I was trying—I wanted to put all the languages that I could. I hope that for the next song I can put more languages, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the relationship between the United States and Latin America, both culturally and politically? Where do you see it going?

RENÉ PÉREZ: I don’t know. You have countries like Venezuela, for example, that they’re very—like, they defend their ideals, and they are very strong, a very strong country, and they are very connected. You have Brazil, that they don’t feel like—they are not enemies, but they are not—they are not in favor of the things that this government do, of course. And you have Uruguay, that you have Mujica. That is great, and also he’s not part of. You have Colombia maybe. Colombia is—and Mexico, maybe they are more into—not the Mexicans, but the government over there, maybe is more into the United States. But almost every country in Latin America, they don’t like that, you know, what is happening with the government and what they do.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to ask you about the future for young people in Puerto Rico, because obviously Puerto Rico, over the last decade, lost population. Because the economic situation is so bad, many of the young people, especially when they graduate from college, are leaving, going to the United States or going to other countries. Your sense of what the future for young people on the island is with the still-unresolved status issue of where—what will be the permanent status of Puerto Rico?

RENÉ PÉREZ: I think there is a lot of young people, and they’re getting aware of what is happening and our political situation. But a lot of people, they don’t care. And they—I feel like they are like sleeping. But it’s because we have been like for 100 years a colony, and the education, our education, is—in terms of history, is just the history of the United States. Like, we don’t take the history of Puerto Rico, maybe a little bit. But it’s a way to make you dependiente — how you say? Dependent.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Dependent, yes.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Or dependiente.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: O dependiente, yeah.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yeah. So, I think right now it’s going to be difficult. If we can connect Puerto Rico with Latin America more and more and more, maybe they wake up, you know? Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you for being with us. We’re going to do part two after the show. I shouldn’t say we, because it’s just going to be Juan, interviewing you in Spanish.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Oh, thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: A Puerto Rican conversation.

RENÉ PÉREZ: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: This is—and we’ll post it online at democracynow.org. René Pérez, also known as “Residente,” with us, co-founder of the Puerto Rican band, Calle 13. The group has won 19 Latin Grammy Awards, a record, also two Grammy Awards. He is cutting a new record here in New York. And we hope to be the ones to premiere it here on Democracy Now! This is Democracy Now! So, go to democracynow.org to watch the interview in Spanish. But next, we’ll go down to Salvador. Stay with us.

Media Options