Related

Guests

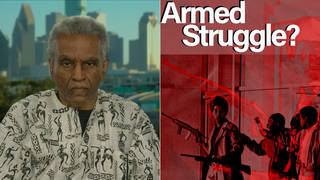

- Johnny Spainmember of the San Quentin Six, friend George Jackson, Black Panther and author of Soledad Brother.

- Lori Andrewsauthor of Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain.

Twenty-five years after Black Panther George Jackson was shot and killed by guards during an escape attempt from San Quentin Prison, we speak with Johnny Spain, the only member of the San Quentin Six convicted of conspiracy, and with Lori Andrews, author of a new book called “Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re listening to Democracy Now! I’m joined now by Pacifica national affairs correspondent Larry Bensky and Salim Muwakkil in Chicago. Twenty-five years ago today, Black Panther George Jackson tried to escape from San Quentin Prison and was gunned down in the prison yard. Here’s an excerpt of an interview with George Jackson.

GEORGE JACKSON: My job is to build, or help build, the prison movement. And like I said, the objective of this movement is to prove to the state that the concentration camp theory won’t work on us, the strategic hamlet theory won’t work on us, and that it’s impossible to concentration camp resisters. The people, the entire joint, the convict class, have related to the idea 100%. And we’ve moved from — not “we,” but I, myself, I’ve always been internationalist. I’ve always been materialist.

AMY GOODMAN: The killing of George Jackson ultimately sparked a number of events, including the bombings of corrections offices in San Francisco and New York and the uprising at Attica prison in New York. The man who was running alongside George Jackson and survived, although survival is a relative term in California’s prisons, was Johnny Spain, the only member of the so-called San Quentin Six convicted in a highly controversial and celebrated political trial. Johnny Spain spent more than two decades behind bars. And now the story of his life has been written in a new book called Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain. It’s by Lori Andrews. And just having finished it, I feel like I’ve been in the bowels of the California prison system for many, many hours. Lori Andrews joins us from Chicago. Johnny Spain is at our studios in Berkeley. Larry?

LARRY BENSKY: Johnny Spain, the events that are recounted so vividly and so effectively, I believe, in this book, Black Power, White Blood, of course, fell most heavily on you. And I was most struck in this book by something that I had not appreciated at the time, having covered this story, as you probably know, and broadcast a lot about it, which was the physical endurance — the physical endurance — that you had to show to survive that period. Maybe we could begin by getting you to tell our listeners what it was like even to come to trial during the trial that ensued from the events of that day 25 years ago physically for you.

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, I think, in terms of just the sheer pain of having metal on your body 15, 16, 17 hours a day and in the form of chains, and having also additional chains attached to you to secure you to a chair that’s secured to the floor, the sheer pain of it was something that you eventually — you never get used to it, but you devise ways to just endure it. And I never thought of myself as someone who would become obsessed or have obsessive behavior, and yet I had become so obsessed with getting those chains removed that I really lost track of significant portions of the trial. And that was — I used to say we were chained up like animals. And then I asked myself, “Well, what animal is chained up like this?” And, in fact, no animal is chained the way we were.

LARRY BENSKY: I attended the trial and saw you in those chains and had no idea, first of all, how heavy they were and how onerous they were and what an effect they were having on your body and, ultimately, on your mind. Lori Andrews, what was the pretext under which the state of California was chaining people in a courtroom, which was surrounded by some of the heaviest security — in fact, I say the heaviest security I’d ever seen?

LORI ANDREWS: Yeah, when you think about it, this was totally unprecedented to have each of the defendants in 25 pounds’ worth of chains, to have choke collars, where they were chained to each other in a line, where guards can pull at their necks when they were brought into the courtroom. And before the trial would begin each day, they would be put in a room alongside of it, where their chains would be attached to hooks in the floor, as you do with elephants at a circus, and that would not allow any of these men to stand erect.

Well, this was unprecedented. There were a lot of other trials going on that were very volatile in California at the time, if you think of the Charles Manson trial and so forth. But, you know, none of the defendants in these other trials had been involved in a Black radical group, as Johnny had with the Black Panthers. And this, I think, was seen as so incredibly threatening that even though there was no evidence that Johnny had actually physically harmed anybody during the breakout attempt at San Quentin, he nonetheless was bound in this way, in a way that made him lose 50 pounds and develop all sorts of back problems. Some days he would have to be shot in the back with a painkiller before he could even make it out of his cell. And so, I think that there was actually very little pretense, other than this incredible worry that J. Edgar Hoover had created about the power of the Black Panthers and the fact that even though there was bulletproof glass in the courtroom and guards with machine guns, that there might be some attempt to free these men as leaders in the Black Panther Party.

AMY GOODMAN: Salim?

SALIM MUWAKKIL: What I was wondering, Lori, is: What’s a nice, soft-spoken attorney like yourself doing consorting with Black Panthers? What drew you to this story?

LORI ANDREWS: Well, actually, my consorting began much earlier. I was raised in the Chicago area in really a biracial environment and, in fact, knew Fred Hampton, who was the leader of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers and had been shot by the FBI when an FBI informant provided the location —

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Floor plan.

LORI ANDREWS: The floor plan — and remember, as a young woman, you know, just seeing what that did in the Chicago community, where at first the local police said that there had been a lot of — they were acting in self-defense and a lot of shots had been fired out of the door, when, actually, you know, people in the neighborhood went to look at it, and it turned out that there were hundreds of shots in and one out. And so, that was a backdrop. My first year in law school was the year that Johnny was on trial in chains. And to see these men chained like slaves at auction, I came back upon the issue in the case, even though the Panthers had fallen out of the news, in 1988, when I realized that, 17 years after the breakout attempt, Johnny’s case was still on appeal, that somehow the courts had not come to terms with the fact that this violated the presumption of innocence. So I got into it as an interest in the legal issues and stayed involved because of his incredible personal story.

LARRY BENSKY: We should maybe bring the listeners up to date, those who weren’t alive then, who don’t remember it, about exactly what happened on August 21st, 1971, 25 years ago today. Somehow or other, George Jackson, who was a leader of the revolutionary African American prisoners in California and had written a famous book Soledad Brother, got a gun and got out into the yard at San Quentin Prison with this gun. And I want to ask you, Johnny Spain, a question which I’ve had occasion to ask two of the other members of the San Quentin Six, as the people who were on trial for this event came to be known, and I’ve never really gotten a complete answer. What was he doing? Was there really a sense, do you think, that he thought that he could get out of such a heavily guarded situation with just a handgun?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, I think, number one, many people, certainly on the West Coast, are still asking the question: Well, was George trying to escape? And I’ve advised those people, they should really pay attention to what George himself said only weeks earlier in The New York Times, that, when asked how would he get out of prison, he says, “Well, I’m going to escape from San Quentin.” So, there was no question in his mind that he needed to try and escape. However, I don’t believe — and I think a real close look at the events at San Quentin on August 21st, 1971, would tell you — that was not the day he planned to escape. However, he had been discovered — the weapon had been discovered, and he had no alternative but to do something. And he didn’t choose to give the weapon up and surrender, so he ran outside.

AMY GOODMAN: Why don’t you tell your portion of the story, how you got involved with this attempted jailbreak?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, being in the adjustment center, which is solitary confinement, along with 29 other prisoners, who never come out on a tier together — no two prisoners are ever allowed on a tier together. And on August 21st, 1971, all the prisoners were out on the floor. And for me, that was a pretty frightening experience in that all the people in the adjustment center were not political prisoners, per se, or had not been locked up for political reasons, and I didn’t know the people. So I wanted to get out of the adjustment center, because the guards were no longer in control. They had been taken hostage. And basically, I found a key and opened the door and got out of there. And as soon as I ran out the door, as the door came open, George followed. And so, I don’t — you know, I don’t believe — the original question, I don’t believe George intended to escape that day.

LARRY BENSKY: Lori Andrews, you cite a note that we’ve known about for some years now, which came to light, which indicates that this whole thing might have been a setup on the part of the FBI or COINTELPRO to actually get George Jackson killed.

LORI ANDREWS: Yeah. George Jackson was corresponding with someone on the outside, James Carr, and describing his escape plan, that he wanted to bring in explosives, which he in fact had visitors bring in to him, that he wanted a gun brought in. And the FBI actually found that letter in a pair of pants at a cleaners, took it out, copied it, told prison authorities about it, gave them a copy and put it back in. Nonetheless, you know, George Jackson was allowed to have visitors in a room where the screen wasn’t put down and where, with other of their prisoners from the adjustment center, they would keep the screen down so there would be no passing back and forth of things. So, it does look like — I mean, clearly, there was advance knowledge of the prison about his escape attempt, not only The New York Times interview, but this letter detailing how it would be done, and yet it seems as if the prison allowed it to go forward, perhaps on the pretext of having the chance to kill George Jackson. In fact, one of the grand jurors who was investigating conditions at the prison, as soon as he heard about this on the radio, went over there, and one of the wardens said to him, you know, “There’s only one good thing that happened today: We killed George Jackson.”

AMY GOODMAN: What were your thoughts, Johnny Spain, when you read that letter that was found by a dry cleaner, that was George Jackson laying out his plans for the escape, that you knew the FBI had before he did escape.

JOHNNY SPAIN: When I became aware of that letter was, of course, during the trial. And it was just — it was an ironic point in the entire proceeding, as far as I was concerned, because there was never evidence put on at trial suggesting that I was a part of the — or saying that I was part of a conspiracy to escape, and yet the prison officials, the local sheriff and the FBI all knew about the escape attempt. And I didn’t see any of them on trial. And I thought that was ironic that — and, ultimately, I was convicted in that case.

LARRY BENSKY: Ironic or infuriating?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, at the time, I mean, along with other things that were happening, it was just another irony. But still, I mean, here I’m on trial for escape, and there’s no evidence put on against me validating that. And yet, the prison is admitting they knew about an escape attempt, and they didn’t do anything to attempt to stop that.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnny Spain, we’re going to come back to this conversation in just a minute. He is the subject of a new book called Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain by Lori Andrews, who joins us, as well. I’m Amy Goodman, with Salim Muwakkil and Larry Bensky. We’ll be back in 60 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, Pacifica Radio’s daily grassroots election show. I’m Amy Goodman, with Larry Bensky and Salim Muwakkil.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Bob Dylan, singing “The Ballad of George Jackson,” on Democracy Now! Jackson was a Black Panther who was shot and killed by prison guards during an escape attempt from San Quentin Prison 25 years ago today, on August 21st, 1971. Johnny Spain was at his side. He was the only member of the San Quentin Six convicted of conspiracy. He joins us from Berkeley, and Lori Andrews joins us from Chicago. Andrews has just written a book called Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain. Salim?

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Lori Andrews, the title of the book, Black Power, White Blood, why did you choose that title, and what does it mean?

LORI ANDREWS: Well, the “Black Power” is rather obvious, because of the efforts of the Black Panthers to take control of communities, to take political power, to reinforce notions of Black pride. The “White Blood” is a little more subtle, and we can think about it both in terms of the killing of a white man, which is essentially what got Johnny put into prison at the age of 17 to begin with, but also the fact of his own white blood. And as I said, I got interested in this area because of the legal case, but then really got involved with writing more about it because of his personal case and the fact that he had been at every stage in which there was a social landmark around race in America — the Deep South in the late ’40s, Watts at the times of the Watts riots, and in the Black Panther Party.

His white mother was married to a white man, had had an affair with a Black man. Her white husband beat her. Her Black lover introduced her to poetry. And yet, because of laws on the books in Mississippi at the time that forbid Blacks and whites from marrying, she was unable to continue her relationship and instead passed off Johnny, within her own home, with her white husband, as white. As Johnny got a little older, his physical appearance changed. Neighbors started burning crosses on the lawn. And when he was 6 years old, his mother made a very tough decision, and she put him on a train in Jackson, Mississippi, essentially as having been raised as a white boy. And he got off two days later to be adopted by a Black couple in South-Central L.A. And so, I think that part of the incredible nature of his story is how he came to terms with his own racial diversity and what lessons that might have for a larger social look at those issues.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Well, it’s kind of — it’s kind of difficult talking about someone when that person is available to answer that question. Johnny, how did it affect you? I mean, how do you square coming to terms with your white blood and the fact that you had been culturally — raised culturally, until that time, as a white boy, and so now you’re suddenly Black? What insights did you gain from that experience?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, at the time, at 6 years old, I don’t think I was aware of any insights that I might have gained, basically because my entire world had been cut off. Everything I had known for the first six years of life had been just eliminated. And I went through periods of anger with my mom, through extraordinary pain of having been given away. And I don’t know that there’s necessarily a psychological distinction between abandonment and what I describe, but I thought what I went through was worse because my mother kept my brothers and sisters, and it’s like I was left with this feeling that I wasn’t good enough to keep. And that set me on a course of trying, of course, to prove something. I wasn’t quite sure what it was I was trying to prove as a kid, but I was trying to belong. And that pushed me usually over the edge of most social circumstances that I came in contact with. It was a horrible feeling. I mean, you don’t come to terms with —

SALIM MUWAKKIL: When you it pushed you over the edge, what do you mean by that?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, I was introduced to sports when I arrived in California, and that was an area that I poured a lot of energy into. And coaches in the later years knew that — some coaches knew that there were some things going on inside of me. They weren’t sure what they were. But I was motivated beyond some instances of things. And there was a world-class athlete, an Olympic gold medalist, Ulis Williams, who said of me as a kid that he had never seen another person in life as competitive as I was. And I just — I didn’t settle for doing things well. I couldn’t be just good at something. I had to be the best. And I would usually push over right over that — excuse me — right over that line, at the expense sometimes of people’s safety. I was trying to fit somewhere so badly that I had a total disregard for other people’s safety — as a kid playing sports is one example.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Do you see any part of that as the motivation driving you toward the Black Panther Party?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, it wasn’t until I actually met George, and he and I became friends — George Jackson — that someone in my life had said to me, when I had disclosed that my mother was white and my father was Black — George said, “Wow! That’s great! That’s really cool!” And it’s the first time anybody had said something positive about it. And, of course, I had lived my entire life feeling horrible about it. And he explained that I had an opportunity to live on both sides. And that was the first time, as a young adult, that I had really ever looked at the benefit here of having lived on both sides.

AMY GOODMAN: And as a leader, to speak to both sides.

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, that’s — ultimately, it became a tool, a big tool, that I used in the prison system to kind of bridge the relationships in there.

LARRY BENSKY: But in between the sports and the prison came another experience, which in fact got you into prison, and that was the gang experience.

JOHNNY SPAIN: Right, right. That was — it’s interesting, because someone asked me a few weeks ago, “Well, wasn’t the gang in fact sort of your surrogate family, or wasn’t this your move toward a family?” And it might have been, somewhere within me, a part of a desire of mine to have that gang as my family, but I didn’t feel close to them, either. And basically, I was just this kid who was out there alone and pretty much trying to figure out from day to day what was going on, how I could best survive this day. But the gang certainly was an outlet, and I gravitated toward it.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Johnny Spain, who has a book written about him, brand-new book out, called Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain. Johnny Spain joins us from California. Lori Andrews, the author of this book, an attorney, is with us from Chicago. Salim Muwakkil and Larry Bensky and I, Amy Goodman, are here in the studios in Chicago and in Washington.

LARRY BENSKY: You know, when I was reading this book — you read about historical injustices and atrocities, and it’s nice to be able to say to yourself sometimes, “Well, you know, fortunately, we’ve gone beyond all that. This could never happen again.” But as I read this book, I had the really chilling feeling that exactly the same thing could be happening right now, that somebody who had been persecuted for racial reasons fell into gang behavior, into an act of violence, into a criminally oriented prison system of all kinds of violence and injustice. We haven’t really gone beyond that at all, have we, Johnny Spain?

JOHNNY SPAIN: You know, I don’t believe we have. And one of the things that Lori has pointed out from time to time is that the laws that were on the books in Mississippi disallowing Black and white people to marry was only erased in 1988. And even then, 47% of the voters there were in favor of keeping that law. And that’s just on one definable level. Basically, I think people — that racism is a lot worse now than even back in the '50s and ’60s, because things are not so clear in terms of where people stand as to racial attitudes or race consciousness attitudes. And people are a lot more sophisticated now, and they're not as overt, so it’s much harder to detect. And yet, some of the same debilitating consequences that arrive from — that come from racism and racist practices are still with us.

And they’re with us to — I mean, looking at my very own — my case, I was one of 130-some kids who committed the same crime in a 10-year period. And basically, that is a felony murder. And as a youth offender, one-third of those kids were minority, whose victims were minority, were tried as youth and sent to youth authority. And one-third of them were white, and they were tried as youth and sent to youth authority. And the other third, which I happened to be a part of, were minorities whose victims were white, and every single one of us was tried as an adult and sent to state prison. Now, you know, that’s — I don’t say that to excuse the action, the crime at 17 years old. That’s not excusable. However, we don’t have a system that equally distributes justice. It just doesn’t exist.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnny Spain, you know, at your trial, your attorney, Charles Garry, said, “A famous writer once said that you can test the values of a nation by the type of prisons it has. Our prisons are hellholes. I wonder how many more San Quentins there are going to be, how many more Soledads, how many more Atticas.” And I wanted to go back to that time, before we take on the issue of prisons in America today, which is something in this election year both the Republicans and the Democrats have basically the same feelings about. But before we do that, I wanted to go back to that time of the trial, because this is a time when people did feel that the state was down upon them, that there was a movement. There was SDS. There was the Black Panthers. There was the underground. And I wanted to get, actually, all of our guests’ perspectives at that time — Larry, who was there at the trial covering it; you, of course, Johnny Spain, who were the subject of this trial; and Salim, what you were doing at this time, in 1976.

LARRY BENSKY: Let’s start with Salim.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Well, I, too, had been a member of the Black Panther Party, but this was in the early — well, ’69 and ’70, the New Jersey branch, which had kind of — began following Eldridge Cleaver after the split between him and Huey. So, I have spent some of that time dealing with these — some of the very same issues that Johnny Spain and the West Coast branch were dealing with. By ’76, I had gone through the Panther Party. I had become a member of the Nation of Islam and gone through that, as well, in my search. So, the turmoil of the era is virtually embodied in my biography.

LARRY BENSKY: Lori? I want to go last. You can tell that.

LORI ANDREWS: Well, I imagine I was in law school at the time. And one of the things that was the most difficult in writing this book was recreating a sense of that time, when revolution seemed possible, when there was a lot of skepticism about government, and people are willing to, as the term of the times was, “by any means necessary” try to right the injustices. As I tracked down people who were very active in that era — Angela Davis, Ericka Huggins, who was on trial with Bobby Seale as part of the New Haven Black Panther trial — I realized that many of them were working for a better world today in different ways. Ericka Huggins, I met her at her ashram, for example. And yet, there aren’t the same institutionalized groups or mechanisms to come together and discuss as there were for young lawyers at that time, you know, different economic systems, ways in which radical change could be made. And I was worried about even writing about it, in terms of it sounding dated or impossible or not being able to really reach this generation of potential activists.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnny Spain, at this point, it seems to be one of the lowest points of your life, and I’d like to know if you actually felt any hope, although the story does not seem to suggest some at this point. I mean, you had Black Panthers who were either assassinated at this point or in prison, most of them. What about your feelings as you went to trial?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, I really thought at the time, in the early '70s, given everything that was happening in the larger society, with the antiwar movement, Black Power movement and what have you, that this trial, in a way, was — it was a mockery of justice. I mean, that was first in my mind. It was just a mockery. You cannot bring human being — present human beings in this fashion and say that there's a presumption of innocence. And yet, at the same time, it was a way of exposing what was going on, so there was sort of hope in the very terror of it. And it’s strange how people grasp really peculiar things to hold onto for hope, but, given that time, I didn’t feel — I actually felt that there were — we were close to having tanks in the street, you know? So — and a lot of people in prison who did not have some of the perspective — in fact, there were people on the street who actually thought that time was coming where there was going to be real radical social transformation in the society. And maintaining hope wasn’t something that was isolated from me, outside of just the sheer horror of that experience. I mean, I can’t tell people how it makes you feel to be chained in that fashion every day and to go to a court of law, where justice is blind, and it’s like, “Wait a minute. Somebody had the blindfold off here.”

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain what the chains were, how exactly your body was chained up?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, first of all, there was a waist chain that was put around your waist and padlocked in the back. And attached to this waist chain were two maybe eight-inch links, link extensions, with a handcuff on each one at the sides. And they would put the handcuff on you, and then they would padlock the first link of the handcuff chain to the belt, the the waist chain, on both sides. Then they would take another singular long chain, padlock it at your back, put it through your legs, bring it up to the front and then padlock that to the front of your waist chain. Then they would loop that, the rest of the length of that chain, around your neck — and, literally, around your neck — and down the back side, which they would padlock that to the back of the waist chain. And then that’s — and then they would put leg shackles on you.

LARRY BENSKY: Salim, that made me think of the Middle Passage, really. I’ve read about slave ships and seen drawings of slave ships where people are chained like that.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: It’s really strange you should say that, because there are some people — you know, the 13th Amendment, when it abolished slavery, it did it for all but inmates. In other words, it took slavery out of the hands of entrepreneurs, private entrepreneurs, and put it into the hands of the state, because the state — often what happened right after slavery was abolished is that people in the South, the Southern states, created offenses so that Blacks who formerly — who were officially free would be re-enslaved as prisoners. So, there’s a very strong connection between the institution of slavery and the incarceration complex that we now have in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to break. When we come back, we’ll continue this discussion. The book we’re talking about and the life we’re talking about is Johnny Spain’s, the book Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain by Lori Andrews, who joins us from Chicago, Johnny Spain from Berkeley. And we’re joined by Larry Bensky and Salim Muwakkil, my co-hosts. I’m Amy Goodman. We’ll be back in 60 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Salim Muwakkil, senior editor at In These Times in Chicago. Larry Bensky, our national affairs correspondent, is joining me in Washington. Our guests are Johnny Spain. A new book is out on his life, Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain. It’s written by attorney Lori Andrews, who joins us from Chicago. Larry, we’ve gone through everyone else. At the time of this trial, you were there. In fact, we were just trying to see a picture right now of George Jackson’s funeral to see if we could find you with your microphone capturing Huey Newton.

LARRY BENSKY: Yes, I was. I was outside the church that day. I did not cover the trial very often, Amy. At KPFA in Berkeley, we had at least six or eight people who were working on this whole constellation of things — antiwar protests, the Black Panthers, COINTELPRO. And I did some of the reporting on it, but I did record Huey Newton outside of the funeral that day in West Oakland.

HUEY NEWTON: George Jackson had every right, every right to do everything possible to preserve his life and the life of his comrades, the life of the people. George Jackson, even after his death, is a legendary figure and a hero — he must be — to the oppressor. This is true. I know it’s true because of the words of the oppressor. To cover their murder, they say that George Jackson killed five people, five oppressors, wounded three, in the run of 30 seconds. You know, I don’t try to look — sometimes I like to look over the fact that it’s physically impossible. But, after all, George Jackson is my hero, and I would like to think that it was possible. I would like to be very happy that George Jackson had the strength. He must of had to be — he’s a superman. Of course, my hero would have to be a superman. And we will raise our children to be like George Jackson, to live like George Jackson and to fight for freedom as George Jackson fought for freedom.

LARRY BENSKY: I had had quite a bit of experience by that time with the Black Panthers. I helped Bobby Seale write his book, A Lonely Rage. I was international chair of the Free Eldridge Cleaver Committee. I was someone who worked on the Black Panther paper on Fillmore Street in San Francisco in 1968 and '69. I knew all these players. And just to bring up what Johnny was saying before about the mood of the times, it's very difficult to recreate it now and to explain to people that many of us did think that revolutionary change was — although it was going to be very difficult, and it wasn’t going to happen immediately, was possible, that there was tremendous amount of organizing. I believe at one point the Black Panther Party newspaper was selling over 100,000 copies, until COINTELPRO started to kill some of the people selling it on the East Coast, and including a friend of mine named Sam Napier, who was assassinated when he came back here to Queens. But it was a very enervating time. And one of the things I have to tell you, Johnny Spain, is, although until I read this book I did not get a sense of what you had physically gone through, there were many of us on the outside who were doing what we did because we knew, basically, that people like you were being tortured and that the society at large did not know about it. And then, as now, there were very few places you could talk about it, KPFA, Pacifica, being one of them.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnny Spain, after you were convicted, while the others were acquitted, convicted of conspiracy to kill the guards that were killed on that day, and you went on to serve your prison sentence, can you talk about the journey you took until you eventually got out in 1988? It came out that Patricia Fagan, one of the jurors, actually, her friend had been, she believed, killed by Geronimo Pratt, a Black Panther. She talked about mulattoes, not during the trial, but afterwards, and how violent they were, and she called you a mulatto. What about that journey until you were eventually freed?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, it’s really interesting. When the verdict — excuse me — when the verdict in the San Quentin trial came down, they read one of the other defendants first, and then, when they called my name, one of the jurors started crying. And I knew what had happened. Just somehow I knew. And I said to myself, “These people have convicted me of this? This is insane.” And I wrote her a letter or note and said, “You know, I really think that you probably did the very best you could, given the circumstances. I know all of the information in this trial was not provided to you. And you need to understand that you didn’t have as much control over the conditions here as you think you might have.”

And that, for me, was saying how serious do I take this conviction. I was already in prison on a life sentence, and they were going to give me additional life sentences. And I always wondered what that means. What? Do you live one sentence and die, and then you come back and you do another one? I don’t know. But I do believe that the prison administration, after the San Quentin trial, publicly stated that I was the most dangerous prisoner in the state of California. And I always loved that one, you know? It’s like the most dangerous person in something. And yet, a year or so after that statement, being that I was an electrician, I finally did get to one of the main lines, maybe a couple years later, and I was issued all sorts of tools — and, you know, hacksaws and screwdrivers and hammers. And it’s just an ironic thing to give the most dangerous person in the state of California prison system a hacksaw and a hammer.

So, I didn’t — and I say that to say I didn’t take too serious the conviction, because that wasn’t the measure that I was going to operate my life from. I knew, I believed in Dennis Riordan and Richard Zitrin and people who were working on — attorneys who were working on that case. I believed they were going to get that case off the books and get me a new trial, a fair trial, and that that would — I believed that fairness would prevail at some point. The other real measure for me was, of course, not merely surviving the prison experience, but trying to find ways to grow while I was in there. And that was very difficult, given that people around me were pretty much invested in being prisoners and being caught up in that prison culture.

LARRY BENSKY: Why don’t you explain to people who haven’t read your book, or who don’t know much about it, what it was like to be in the isolation unit, which Lori Andrews wrote about so vividly? What is that, the hole?

JOHNNY SPAIN: Basically, there’s nothing in that cell. There’s just a five-by-eight concrete room that has a hole in the floor where you go to the bathroom. And they can lock an outer door to even shut it off more, more so, so they can actually cut off the daylight from you. And I just remember that I’ve seen people who had been four or five months in the hole, who had come out pretty destroyed. And I knew that these people were going to try and keep me in this place as long as possible. And I had to just immediately devise a way to make this experience OK for me.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Lori Andrews, what Larry, Larry Bensky, pointed out, as well as Johnny, that there were people on the outside who seemed to be much more concerned about the lives of political prisoners than we seem to be today. Do you see that as the case?

LORI ANDREWS: I see it absolutely as the case. And I think that Johnny’s own cases, own legal actions, and the attorneys, like Dennis Riordan and Fay Stender, working on his behalf, changed some of these oppressive conditions in prison — for example, at least got it so you could only be put for a month in the hole instead of six months, because people were destroyed. There was an incident, shortly before Johnny was put in the hole, where guards threw tear gas in the hole with someone and then closed that door in front of the bars, and the person died, because you can’t be in that small a space in that situation. And so, there were a variety of ways in which there was at least an interest at that time in getting some of this changed, in terms of, for example, getting reading materials in to prisoners.

And what I see now, particularly over the past year — and, as Amy mentioned, it’s an issue in the election — is this return to the horrible conditions that the cases had challenged. Five states have reinstated chain gangs, for example. You’re seeing a lot of the educational programs being stopped in the prisons in order to make room for more beds, and so forth. And there’s this selling of prison, where it’s become this incredible industry in America — the third-largest industry in California, for example — where you’re seeing companies that used to get fat contracts out of the military — that’s dried out — now going into the, quote, “prison services industry.” And, you know, the three-strikes laws, the longer sentences, all this in light of 90 years’ worth of studies that have shown that that has no effect on recidivism except for white-collar crime. So, I’m not only seeing less of a social interest in doing something about it; I’m seeing us fooling ourselves by thinking we can take care of crime by these measures and by reinstating in superprisons, as in Maryland and in Pelican Bay in California, some of the very worst conditions that Johnny and others had to live through in that era.

AMY GOODMAN: Lori Andrews, you and Salim are in Chicago, where the Democratic convention will be taking place next week, and it seems that the Democrats can’t do enough to outdo the Republicans around the issue of prisons and their version of law and order. Johnny Spain, you’re now a community activist, out for, what, around eight years now, free for eight years, at least from prison. What are your thoughts on prisons today? And are you involved with prison activism?

JOHNNY SPAIN: I’ve taught criminal justice courses at Stanford and UC Berkeley. And I chose that avenue because I felt that there would be social scientists and young attorneys who could deal more effectively and who would be needed to assist in dealing with the prison system phenomenon that certainly is going on in California. But, for me, it’s very clear in my mind, when people talk about criminal justice, that they are not provided all of the facts or the necessary facts to make intelligent decisions about what to do in terms of trying to impact public safety, for instance. People — you cannot get elected these days unless you take a hard stance against crime. And that’s unfortunate, because the hard stance against crime has developed to a point where it is actually contributing to the problems we are facing in terms of public safety and crime itself.

And I say that because, nationally, we release 95% of all the people we send to prison, and when we snatch education opportunities, vocational opportunities, therapeutic endeavors in prison — snatch those away from prisoners, under some guise of babying the prisoners, all of that sounds great, except we’re going to release that person. And that person will ride the bus with us, walk down the street. So, we can beat them every day, if we choose to, but they’re still going to walk down the street with us. And I think, just as a very basic survival question for each person: Do you want to walk down the street with ex-offenders who are educated and have been through therapy and who have vocations and who have developed communication skills and conflict resolution skills, or do you want to walk down the street with someone who’s been beaten every day or abused and dehumanized by his circumstance? And the choice is — it really is ours. But politicians are certainly not providing us with a clear picture of that choice. In fact, they’re saying, “Build more prisons.” In California alone, which is five times over capacity in its prison system, is building more prisons every day, and yet still releasing 95% of the people. And what the politicians do not tell you is that our entire criminal justice system in California only deals with 9.7% of the reported crime. I mean, when you think about — I mean, you think about that, you know, like, what are two new prisons going to do? What are 10, 20 new prisons going to do in the face of that kind of statistic?

LORI ANDREWS: Well, Johnny, I’ll tell you they’re going to do. The RAND Corporation says that — that just did a study, released in June, about California prisons, and they say that if they keep going this rate, it’s going to undermine the whole state university system by the year 2002 and the whole state economy by 2005. I mean, they’ve essentially gone in the past 10 years from 4% of the budget going to the Department of Corrections to over 8, while higher education in California has dropped considerably. And so, we’re heading on a path that just won’t work.

LARRY BENSKY: To Johnny Spain, then, what does society do about the type of person Johnny Spain was when he was 17? Alienate — [no audio]

JOHNNY SPAIN: Well, I think a different, more effective way would be to take into account how a person arrived at a particular point in their life where they committed a horrible action. Absent that, we don’t know why people are doing what they’re doing. And to continue to pour money into an endeavor that is making the problem worse, in that our prison system is clearly conditioning people not to be able to be law-abiding citizens upon their release — now, there’s no question that we cannot have 17-year-olds running around society shooting people. There’s no question about that. And in those cases, or whoever, whatever age they happen to be, those people are going to have to be isolated at some point. But if we’re going to release that person at a rate of 95%, even people who shoot people, if we’re going to release that person, we need to ask ourselves a basic question: How do we want that person to — you know, where do we want to influence the chances of that person’s predictable behavior? And basically, I say take into account how that person developed the way they did, not to excuse the action, but rather to inform us as a society. Maybe there are some things socially going on, some conditions, that we need to address. For instance, 91% of the people on California’s death row came from foster care. And we are constantly pulling more money away from foster care, away from those kinds of efforts that help kids adjust through those difficult times, and putting it into the other end: “Let’s pour billions of dollars into the execution end of it.” I guess I’m saying that we need to focus more on a rebuilding of community. I don’t know that I have the answer. I know we need to rebuild community, and not in terms of community policing.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Johnny Spain, I want to thank you very much for joining us, and Lori Andrews, author of the book Black Power, White Blood: The Life and Times of Johnny Spain. And Larry Bensky and Salim Muwakkil have been with us from Chicago and here in Washington. Julie Drizin has produced Democracy Now! It is engineered by Kenneth Mason at WPFW. Thanks to Errol Maitland, Bernard White and Elombe Brath of WBAI and Jim Bennett of KPFA. If you’d like a copy of today’s show, you can call 1-800-735-0230 — that’s 1-800-735-0230 — or call our comment line and leave your thoughts at 202-588-0999 extension 313. That’s 202-588-0999 extension 313. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for listening to another edition of Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now!

Media Options