Topics

Today is a national holiday commemorating July 4, when American colonies declared their independence from England in 1776. While many in the U.S. hang flags, attend parades and watch fireworks, Independence Day is not a cause of celebration for everyone.

For Native Americans it is a bitter reminder of colonialism, which brought disease, genocide and the destruction of their culture and way of life.

For African Americans, Independence Day did not extend to them. While white colonists were declaring their freedom from the crown, that liberation was not shared with millions of Africans who were captured, beaten, separated from their families and forced into slavery thousands of miles from home.

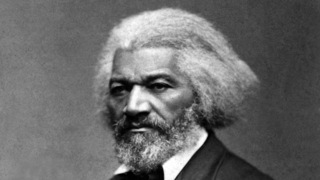

Today we will go back more than 150 years to hear one of the most powerful voices of the abolition movement: Frederick Douglass. Born a slave in Maryland in 1818, Douglas escaped from slavery in the 1830s and became a leader in the growing abolition campaign through lectures and his anti-slavery newspaper, The North Star. He would become a major civil rights leader in the United States. Douglass gave his Independence Day oration in 1852.

Today we’ll hear excerpts of that speech as part of a dramatic reading of Howard Zinn’s classic work: A People’s History of the United States.

The great historian gathered with actors and writers several months ago at the 92nd Street Y in New York.

The cast included Alfre Woodard, Danny Glover, Marisa Tomei, Kurt Vonnegut, James Earl Jones and others.

- Howard Zinn, author, A People’s History of the United States.

- James Earl Jones, actor.

- Harris Yulin, actor.

- Andre Gregory, actor.

- Jeff Zinn, Howard Zinn’s son.

- Marisa Tomei, actress.

- Danny Glover, actor.

- Kurt Vonnegut, author.

- Alfre Woodard, actress.

- Alice Walker, author, novelist and essayist.

Archived Democracy Now! Programs Featuring Howard Zinn<-> Democracy Now! Interviews Alice Walker__

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today is a national holiday commemorating July 4th, when American colonies declared their independence from England, 1776. While many in the U.S. hang flags, attend parades and watch fireworks, Independence Day is cause of celebration not for everyone. For Native Americans, it’s a bitter reminder of colonialism, which brought disease, genocide and the destruction of their culture and way of life. For African Americans, Independence Day did not extend to them. While white colonists were declaring their freedom from the crown, that liberation was not shared with millions of Africans captured, beaten, separated from their families and forced into slavery thousands of miles from home.

Today, we will go back more than 150 years to hear one of the most powerful voices of the abolition movement, Frederick Douglass, born a slave in Maryland in 1818. Douglass escaped from slavery in the 1830s and became a leader in the growing campaign against slavery through lectures and his anti-slavery newspaper, The North Star. Douglass gave his Independence Day oration in 1852. He would become a major civil rights leader in the United States.

Today we’ll hear excerpts of that speech as part of a dramatic reading of Howard Zinn’s classic work, A People’s History of the United States. The great historian gathered with actors and writers several months ago at the 92nd Street Y in New York. He gathered with Alice Walker, Alfre Woodard, Danny Glover, Kurt Vonnegut, James Earl Jones and others for that reading. We begin with James Earl Jones reading from Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States.

HOWARD ZINN: [read by James Earl Jones] My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals a fierce conflict of interest. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, is not to be on the side of the executioners.

Thus, in that inevitable taking of sides which comes from selection and emphasis in history, I prefer to tell the story of the discovery of America from the viewpoint of the Arawaks, of the Constitution from the standpoint of the slaves, of the rise of industrialism as seen by the young women in the Lowell textile mills, the conquest of the Philippines as seen by black soldiers on Luzon, the postwar American empire as seen by peons in Latin America. And so on, to the limited extent that any one person, however he or she strains, can “see” history from the standpoint of others.

My point is not to grieve for the victims and denounce the executioners. Those tears, that anger, cast into the past, deplete our moral energy for the present. And the lines are not always clear. In the long run, the oppressor is also a victim. In the short run, the victims, themselves desperate and tainted with the culture that oppresses them, turn on other victims.

Still, understanding the complexities, this book will be skeptical of governments and their attempts, through politics and culture, to ensnare ordinary people in a giant web of nationhood pretending to a common interest. I will try not to overlook the cruelties that victims inflict on one another as they are jammed together in the boxcars of the system. I don’t want to romanticize them. But I do remember (in rough paraphrase) a statement I once heard: “The cry of the poor is not always just, but if you don’t listen to it, you will never know what justice is.”

HOWARD ZINN: Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the islands, beaches, and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. Columbus later wrote of this in his log:

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS: [read by Harris Yulin] They … brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells. They willingly traded everything they owned … They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features. … They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane … They would make fine servants. … With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

HOWARD ZINN: We have no Indian voices to speak for the men and women of Hispaniola, but we have the volumes written by the Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas, who was an eyewitness to what happened after Columbus came.

BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS: [read by Andre Gregory] These people are by nature the most humble, patient, and peaceable, holding no grudges, free from embroilments, neither excitable nor quarrelsome. These people are the most devoid of rancors, hatred or desire for vengeance of any people in the world. …

Yet into this sheepfold … there came some Spaniards, who immediately behaved like ravening wild beasts, wolves, tigers, or lions that had been starved for many days. And Spaniards have behaved in no other way during the past forty years, down to the present time, for they are still acting like ravening beasts, killing, terrorizing, afflicting, torturing, and destroying the native peoples, doing all of this with the strangest and most varied new methods of cruelty, never seen or heard of before, and to such a degree that this Island of Hispaniola, once so populous (having a population that I estimated to be more than three millions) has now a population of barely two hundred persons.

HOWARD ZINN: Our political leaders like to pretend that there are no classes in this country, that all of us have the same interest—Exxon and me, George Bush and you. But we’ve always had classes in this country, class conflict, class struggle. Before the American Revolution, there were riots of the poor against the rich, of tenants against landlords, flour riots and food riots. During the Revolution, in George Washington’s army, there were mutinies of soldiers who resented the privileges of the officer class and the way they themselves were treated. And they mutinied, and then Washington ordered the execution of some of them, execution done by their fellow mutineers. After the war, veterans who had been given small amounts of land found themselves so heavily taxed they couldn’t meet their payments. In western Massachusetts, thousands of farmers surrounded the courthouses where their farms were being auctioned off and refused to allow the courts to proceed. Eventually Shays’ Rebellion, as it was called, was crushed, but it put a scare into the Founding Fathers, and when they met in 1787, a year later, to create a Constitution, they made sure to set up a government strong enough to put down the uprisings of the poor. These are the words of one of the participants in Shays’ Rebellion, a man named Plough Jogger.

PLOUGH JOGGER: [read by Jeff Zinn] I’ve labored hard all my days and fared hard. I have been greatly abused, have been obliged to do more than my part in the war; been loaded with class rates, town rates, province rates, Continental rates, and all rates … been pulled and hauled by sheriffs, constables and collectors, and had my cattle sold for less than they were worth.

I have been obliged to pay and nobody will pay me. I have lost a great deal by this man and that man and t’other man, and the great men are going to get all we have, and I think it is time for us to rise and put a stop to it, and have no more courts, nor sheriffs, nor collectors, nor lawyers, and I know that we are the biggest party, let them say what they will. … We’ve come to relieve the distresses of the people. There will be no court until they have redress of their grievances.

HOWARD ZINN: What is too often overlooked in the triumphal story of the growth of American industry in the nineteenth century is the human cost of that triumph: the lives cut short, the maimed bodies of the men and women who worked in the factories, the mills. In the Lowell, Massachusetts, textile mills of 1836, where girls went to work at the age of twelve and often died by the time they were twenty-five, one of the first strikes of mill girls took place. It is described by one of them, Harriet Hanson.

HARRIET HANSON: [read by Marisa Tomei] When it was announced that wages were to be cut down, great indignation was felt, and it was decided to strike, en masse. This was done. The mills were shut down, and the girls went in procession from their several corporations to the “grove” on Chapel Hill, and listened to “incendiary” speeches. …

One of the girls stood on a pump, and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience. …

My own recollection of this first strike (or “turn out” as it was called) is very vivid. I worked in a lower room, where I had heard the proposed strike fully, if not vehemently, discussed; I had been an ardent listener to what was said against this attempt at “oppression” on the part of the corporation, and naturally I took sides with the strikers. When the day came on which the girls were to turn out, those in the upper rooms started first, and so many of them left that our mill was at once shut down. Then, when the girls in my room stood irresolute, uncertain what to do, asking each other, “Would you?” or “Shall we turn out?” and not one of them having the courage to lead off, I, who began to think they would not go out, after all their talk, became impatient, and started on ahead, saying, with childish bravado, “I don’t care what you do, I am going to turn out, whether any one else does or not;” and I marched out, and was followed by the others.

As I looked back at the long line that followed me, I was more proud than I have ever been at any success I may have achieved.

HOWARD ZINN: As part of the long process of driving the Indians off their native lands, Andrew Jackson in 1830s signed an order to remove by force the Five Civilized Tribes from their territory in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, and drive them westward across the Mississippi. There followed what became known as The Trail of Tears, in which sixteen thousand men, women, and children, surrounded by the United States Army, made the long trip westward, and four thousand of them died. The Cherokees and Seminoles resisted, and here they speak to the government of the United States.

THE CHEROKEES: [read by Danny Glover] We are aware that some persons suppose it will be for our advantage to remove beyond the Mississippi. We think otherwise. Our people universally think otherwise. … We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to remain without interruption or molestation. The treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursuance of treaties, guarantee our residence and our privileges and secure us against intruders. Our only request is, that these treaties be fulfilled, and these laws executed.

We entreat those to whom the foregoing paragraph are addressed, to remember the great law of love: “Do to other as ye would that others would do to you.” We pray them to remember that, for the sake of principle, their forefathers were compelled to leave, therefore driven from the old world, and that the winds of persecution wafted them over the great waters and landed them on the shores of the new world, when the Indian was the sole lord and proprietor of these extensive domains. Let them remember in what way they were received by the savage of America, when the power was in his hand. …

We were all made by the same Great Father, and are all alike His Children. We all come from the same Mother, and were suckled at the same breast. Therefore we are brothers, and as brothers, should treat together in an amicable way.

THE SEMINOLES: [read by Danny Glover] Your talk is a good one, but my people cannot say they will go. We are not willing to do so. If suddenly we tear our hearts from the homes around which they are twined, our heartstrings will snap.

HOWARD ZINN: Women, black and white, played a critical part in the building of the antislavery movement in the United States. They worked in antislavery societies all over the country, gathering thousands of petitions to Congress. But when, in 1840, a World Anti-Slavery Society convention met in London, there was a fierce argument about whether women could attend. The final vote was that they could only attend meetings in a curtained enclosure. They sat in silent protest in the gallery, and when they returned to the United States they began to lay the basis for the first Women’s Rights Convention in history. It was held at Seneca Falls, New York, where Elizabeth Cady Stanton lived as a mother, a housewife, full of resentment at her condition, declaring: “A woman is a nobody. A wife is everything.” The convention was attended by three hundred women and some men, who adopted a Declaration of Principles, making use of the language and rhythm of the Declaration of Independence.

DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS AND RESOLUTIONS: [read by Myla Pitt] We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. …

When a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled. …

[Man] has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation—in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: Read by Myla Pitt. Back to Howard Zinn, in this Democracy Now! special.

HOWARD ZINN: Frederick Douglass, once a slave, became a brilliant and powerful leader of the anti-slavery movement. In 1852, he was asked to speak in celebration of the Fourth of July.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: [read by James Earl Jones] Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? And am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you this day rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?

What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is a constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes that would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation of the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of these United States at this very hour.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour forth a stream, a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and the crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

HOWARD ZINN: John Brown, more than any other white American, devoted his life, and finally sacrificed it, on behalf of freedom for the slave. His plan, impossible and courageous, was to seize the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with a band of black and white abolitionists and set off a revolt of slaves throughout the South. The plan failed.

Some of his men, including two of his own sons, were killed. John Brown was wounded, captured, sentenced to death by hanging by the state of Virginia, and with the enthusiastic approval of the government of the United States. When he was put to death, Ralph Waldo Emerson said, he will make the gallows holy as the cross.

Here, John Brown addresses the court that ordered his hanging.

JOHN BROWN: [read by Harris Yulin] Had I interfered in the manner which I admit … had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, [either] father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right, and every man in this Court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This Court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or, at least, the New Testament. That teaches me that all things “whatsoever I would that men should do unto me, I should do even so to them.” […] I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done, in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children, and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit: so let it be done!

HOWARD ZINN: Twenty-two years later, in 1881, Frederick Douglass was asked to speak at a college in Harpers Ferry.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: [read by James Earl Jones] If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery. If we look over the dates, places and men for which this honor is claimed, we shall find that not Carolina, but Virginia, not Fort Sumter, but Harpers Ferry and the arsenal, not Colonel Anderson, but John Brown, began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free republic. Until that blow was struck, the prospect of freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises. When John Brown stretched forth his arm, the sky was cleared.

HOWARD ZINN: After the Civil War, with the federal government enforcing the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, guaranteeing the right to vote to black people, African Americans were elected to governing bodies throughout the South. But after a few years of what might be called “Radical Reconstruction,” the political and business interests of the North made a deal with those of the South, to withdraw federal power and allow the white South to have its way. Henry McNeal Turner, elected to the state legislature of Georgia, was expelled by that body in 1872, but before he left, he addressed his colleagues.

HENRY McNEAL TURNER: [read by Danny Glover] Mr. Speaker, I wish the members of this House to understand the position that I take. I hold that I am a member of this body. Therefore, sir, I shall neither fawn or cringe before any party, nor stoop to beg them for my rights. … I am here to demand my rights, and to hurl thunderbolts at the men who would dare to cross the threshold of my manhood. …

The scene presented in this House, today, is one unparalleled in the history of the world. … Never, in the history of the world, has a man been arraigned before a body clothed with legislative, judicial or executive functions, charged with the offense of being of a darker hue than his fellow-men. … [I]t has remained for the State of Georgia, in the very heart of the nineteenth century, to call a man before the bar, and there charge him with an act for which he is no more responsible than for the head which he carries upon his shoulders. The Anglo-Saxon race, sir, is a most surprising one. … I was not aware that there was in the character of that race so much cowardice, or so much pusillanimity. … I tell you, sir, that this is a question which will not die today. This event shall be remembered by posterity for ages yet to come, and while the sun shall continue to climb the hills of heaven. …

[W]e are told that if black men want to speak, they must speak through white trumpets; if black men want their sentiments expressed, they must be adulterated and sent through white messengers, who will quibble, and equivocate, and evade, as rapidly as the pendulum of a clock. …

The great question, sir, is this: Am I a man? If I am such, I claim the rights of a man. …

Why, sir, though we are not white, we have accomplished much. We have pioneered civilization here; we have built up your country; we have worked in your fields, and garnered your harvests, for two hundred and fifty years! And what do we ask of you in return? Do we ask you for compensation for the sweat our fathers bore for you, for the tears you have caused, and the hearts you have broken, and the lives you have curtailed, and the blood you have spilled? Do we ask retaliation? We ask it not. We are willing to let the dead past bury its dead; but we ask you now for our RIGHTS.

HOWARD ZINN: The orthodox texts in American history pay much attention to what was called “a splendid little war,” the victory of the United States in the three-month-long Spanish-American War of 1898. But these texts slide quickly over the bloody conquest of the Philippines that went on for years, which President McKinley said was necessary to “civilize and Christianize” the Filipinos, and which Theodore Roosevelt hailed as the newest outpost of the American Empire. Roosevelt loved war and militarism, and when the Army massacred 600 Moros on a southern Island in the Philippines in 1906, Roosevelt congratulated the commanding general. Here is Mark Twain’s response:

MARK TWAIN: [read by Kurt Vonnegut] This incident burst upon the world last Friday in an official cablegram from the commander of our forces in the Philippines to our Government at Washington. The substance of it was as follows: A tribe of Moros, dark-skinned savages, had fortified themselves in the bowl of an extinct crater not many miles from Jolo; and as they were hostiles, and bitter against us because we have been trying for eight years to take their liberties away from them, their presence in that position was a menace.

Our commander, Gen. Leonard Wood, ordered a reconnaissance. It was found that the Moros numbered six hundred, counting women and children; that their crater bowl was in the summit of a peak or mountain 2,200 feet above sea level, and very difficult of access for Christian troops and artillery. Then General Wood ordered a surprise, and went along himself to see the order carried out.

Gen. Wood’s order was, “Kill or capture the six hundred.” There, with 600 engaged on each side, we lost 15 men killed outright, and we had 32 wounded—counting that nose and that elbow. The enemy numbered 600—including women and children—and we abolished them utterly, leaving not even a baby alive to cry for its dead mother. This is incomparably the greatest victory that was ever achieved by the Christian soldiers of the United States.

So far as I can find out, there was only one person among our eighty millions who allowed himself the privilege of a public remark on this great occasion—that was the President of the United States. All day Friday, he was as studiously silent as the rest. But on Saturday, he recognized that his duty required him to say something, and he took his pen and performed that duty. This is what he said:

Washington, March 10. Wood, Manila: I congratulate you and the officers and men of your command upon the brilliant feat of arms wherein you and they so well upheld the honor of the American flag. (Signed) Theodore Roosevelt.

I have read carefully the treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.

HOWARD ZINN: The IWW, Industrial Workers of the World, was a radical labor organization of the early twentieth century. It organized all workers—black, white, men, women, native-born, foreign, skilled, unskilled—which the American Federation of Labor refused to do. Its goal was revolutionary: to take over the industrial system and run it for the benefit of the people. When immigrant women in the textile mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts, went on strike in 1912, they were met with police violence and judicial intimidation. The IWW poet and organizer Arturo Giovannitti was arrested on spurious charges for murder. Here is his speech to the jury, which found him innocent.

ARTURO GIOVANNITTI: [read by Jeff Zinn] Mr. Foreman and gentlemen of the Jury: It is the first time in my life that I speak publicly in your wonderful language, and it is the most solemn moment in my life. …

There has been brought only one side of this great industrial question, only the method and only the tactics. But what about … the ethical pan of this question? … What about the better and nobler humanity where there shall be no more slaves, where no man will ever be obliged to go on strike in order to obtain fifty cents a week more, where children will not have to starve any more, where women no more will have to go and prostitute themselves … where at last there will not be any more slaves, any more masters, but just one great family of friends and brothers.

They say you are free in this great and wonderful country. I say that politically you are, and my best compliments and congratulations … But I say you cannot be half free and half slave, and economically all the working class in the United States are as much slaves now as the Negroes were forty and fifty years ago; because the man that owns the tool wherewith another man works, the man that owns the house where this man lives, the man that owns the factory where this man wants to go to work—that man owns and controls the bread that that man eats and therefore owns and controls his mind, his body, his heart and his soul. …

I am twenty-nine years old—not quite … I have a woman that loves me and that I love. I have a mother and father that are waiting for me. I have an ideal that is dearer to me than can be expressed or understood. And life has so many allurements and it is so nice and so bright and so wonderful that I feel the passion of living in my heart and I do want to live. …

Whichever way you judge, gentlemen of the jury, I thank you.

HOWARD ZINN: In the year 1914, a thousand miners, with wives and children, who had gone on strike against the Rockefeller-owned coal mines in southern Colorado, were holding out in a tent colony near the tiny hamlet of Ludlow. One day in April, the National Guard, financed by Rockefeller, began pouring machine-gun fire into the tent colony, and then came down from the hills and set fire to the tents. The next day the bodies of eleven children and two women were found, suffocated and burned to death. This became known as the Ludlow Massacre. Mother Mary Jones, eighty-two-year-old organizer for the mine workers, had come to Colorado to support the miners, and on the eve of their strike, as they gathered in the Opera House in Trinidad, she spoke to them.

MOTHER MARY JONES: [read by Alfre Woodard] What would the coal in the mines be worth if you did not work to take it out? The time is ripe for you to stand like men. I know something about strikes. I didn’t go into them yesterday. I was carried eighty-four miles and landed in jail by a United States marshal in the night because I was talking to a miners’ meeting. The next morning I was brought to court and the judge said to me, “Did you read my injunction? Did you understand that the injunction told you not to look at the miners?” “As long as the Judge who is higher than you leaves me sight, I will look at anything I want to,” said I. The old judge died soon after that and the injunction died with him. At another time when in the courtroom the bailiff said to me, “When you are addressing the court you must say 'Your Honor.'” “I don’t know whether he has any or not,” said I. Someone said to me, “You don’t believe in charity work Mother.” No I don’t believe in charity; it is a vice. We need the upbuilding of justice to mankind; we don’t need your charity, all we need is an opportunity to live like men and women in this country. I want you to pledge yourselves in this convention to stand as one solid army against the foes of human labor. Think of the thousands who are killed every day and there is no redress for it. We will fight until the mines are made secure and human life valued more than props. Look things in the face. Don’t fear a governor; don’t fear anybody. You pay the governor; he has the right to protect you. You are the biggest part of the population in the state. You create its wealth, so I say, “let the fight go on; if nobody else will keep on, I will.”

HOWARD ZINN: In the summer of 1964, black men and women in Mississippi, joined by a thousand young volunteers from the North, formed the Freedom Democratic Party, in defiance of the all-white Democratic Party of Mississippi. When the Democratic National Convention met in Atlantic City, black activists in the Freedom Democratic Party traveled by bus from Mississippi to demand that black people, who were 40 percent of the population in Mississippi, should get 40 percent of the seats at the convention. Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper from Mississippi, spoke to the credentials committee, citing her own experience about what happened to black people in Mississippi who tried to vote. Her eloquence on this occasion, nationally televised, so worried President Lyndon Johnson that he issued a White House announcement to interrupt her testimony. The Democratic Party refused to seat the black delegates, instead offering them two non-voting seats, which they refused. Here is a portion of Mrs. Hamer’s testimony.

FANNIE LOU HAMER: [read by Alfre Woodard] Mr. Chairman, and the Credentials Committee, my name is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, and I live at 626 East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi, Sunflower County, the home of Senator James O. Eastland, and Senator Stennis.

It was the 31st of August in 1962 that 18 of us traveled 26 miles to the country courthouse in Indianola to try to register to [vote] to become first-class citizens. … [T]he plantation owner came, and said, “Fannie Lou, if you don’t go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave … because we are not ready for that in Mississippi.” And I addressed him and told him and said, “I didn’t [go down there] to register for you. I [went down] to register for myself.”

I had to leave that same night. …

And in June the 9th, 1963, I had attended a voter registration workshop, was

returning back to Mississippi. Ten of us was traveling by the Continental Trailway bus. When we got to Winona, Mississippi, … it was a State Highway Patrolman and a Chief of Police ordered us out. …

When they found out who I was, they said, “You nigger bitch, we’re gonna make you wish you were dead.” They made me lay on my face, and they ordered two Negro prisoners to beat me with a blackjack. That was unbearable. The first prisoner beat me until he was exhausted, and then the second Negro began to beat me. … They beat me until my body was hard, until I couldn’t bend my fingers or get up when they told me to. …

All of this on account that we wanted to register to vote, to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings—in America? I thank you.

HOWARD ZINN: In the struggle for racial equality, not all black people accepted Martin Luther King’s message of love and nonviolence. Soon after the 1963 March on Washington, in which King spoke of his “dream,” four black girls were killed in the bombing of a Birmingham church. For Malcolm X, who grew up in a northern ghetto, spent time in prison, became a Muslim, this pointed up the limitations of the civil rights movement. That fall, he addressed a meeting in Detroit. Two years later, he would be assassinated.

MALCOLM X: [read by James Earl Jones] As long as the white man sent you to Korea, you bled. He sent you to Germany, you bled. He sent you to the South Pacific to fight the Japanese, you bled. You bleed for the white man, but when it comes time to seeing your own churches being bombed, and little black girls murdered, you haven’t got any blood. You bleed when the white man says bleed, you bite when the white man says bite, and you bark when the white man says bark. I hate to say this about us, but it’s true. How are you going to be nonviolent in Mississippi, and violent, as you were, in Korea? How can you justify being nonviolent in Mississippi and Alabama, when your churches are being bombed, and your little girls are being murdered?

If violence is wrong in America, violence is wrong abroad. If it is wrong to be violent defending black women and black children and black babies and black men, then it is wrong for America to draft us and make us violent abroad to defend her. And if it is right for America to draft us, and teach us how to be violent in defense of her, then it is right for you and me to do whatever is necessary to defend our own people right here in this country.

Right at that time Birmingham had exploded … that’s when Kennedy sent in the troops, down in Birmingham. After that, Kennedy got on the television and said, “This is a moral issue.” That’s when he said he was going to put out a civil rights bill. And when he mentioned civil rights bill and the Southern crackers started talking about how they were going to boycott and filibuster it, then the Negroes started talking about how they were going to march on Washington, march on the Senate, march on the White House, march on the Congress, tie it up, bring it to a halt, not let the government proceed. They even said they were going out to the airport and lie down on the runway and not let any airplanes land. I’m telling you what they said. That was revolution. That was revolution. That was the black revolution.

It was the grassroots out there in the street. It scared the white man to death, scared the white power structure in Washington, D.C., to death. I was there. When they found out this black steamroller was going to come down on the capital, they called in those national Negro leaders that you respect and said, “Call it off.” Kennedy said, “Look, you’re letting this thing go too far.” And Old Tom said, “Boss, I can’t stop it, because I didn’t start it.” I’m telling you what they said. They said, “I’m not even in it, much less at the head of it.” They said, “These Negroes are doing things on their own.”

HOWARD ZINN: Many of the national leaders of the civil rights movement thought they should not speak out about the war in Vietnam, that this would hurt the cause of black people. But Martin Luther King Jr. decided he could not be silent. April 4th, 1967, he spoke at the Riverside Church in New York.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: [read by Danny Glover] I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice. … “A time comes when silence is betrayal.” That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam. …

In 1957 when a group of us formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, we chose as our motto: “To save the soul of America.” … In a way we were agreeing with Langston Hughes, that black bard of Harlem, who had written earlier:

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath —

America will be! …

Somehow this madness must cease. We must stop now. I speak as a child of God and brother to the suffering poor of Vietnam. I speak for those whose land is being laid waste, whose homes are being destroyed, whose culture is being subverted. I speak for the poor of America who are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home and death and corruption in Vietnam. I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken. I speak as an American to the leaders of my own nation. The great initiative in this war is ours. The initiative to stop it must be ours. …

I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a “thing-oriented” society to a “person-oriented” society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered. …

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. … The Western arrogance of feeling that it has everything to teach others and nothing to learn from them is not just. A true revolution of values will lay hands on the world order and say of war: “This way of settling differences is not just.” This business of burning human beings with napalm, of filling our nation’s homes with orphans and widows, of injecting poisonous drugs of hate into veins of people normally humane, of sending men home from dark and bloody battlefields physically handicapped and psychologically deranged, cannot be reconciled with wisdom, justice and love. A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death. …

Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter—but beautiful—struggle for a new world.

AMY GOODMAN: Danny Glover, reading Dr. Martin Luther King. Today, on this Independence Day special of Democracy Now!, a reading of excerpts of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, with Alice Walker, Myla Pitt, Jeff Zinn, Howard’s son, Marisa Tomei, James Earl Jones, Danny Glover, Yulin Harris, Kurt Vonnegut and others, read at the 92nd Street Y.

Media Options