Topics

On the first anniversary of the coup in Haiti, we look back at Democracy Now!'s exclusive broadcast when President Jean-Bertrand Aristide went on camera for the first time to charge the U.S. kidnapped him and overthrew his government. We also broadcast the interview of his bodyguard Franz Gabriel who describes the events surrounding Aristide's ouster. [includes rush transcript]

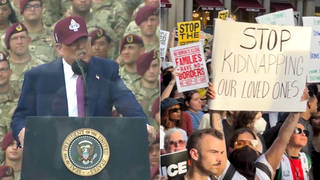

Before we hear from Aristide, we wanted to go back to those days and listen to how the Bush administration was spinning the ouster.

On March 1, Democracy Now! broke the story that Aristide was directly accusing the US of overthrowing him in a coup, kidnapping him and taking him by force to the Central African Republic. That day US official after US official was asked about Aristide’s charge. Let’s listen to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of State Colin Powell and White House Secretary Scott McClellan.

- Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld

- Secretary of State Colin Powell

- White House Press Secretary Scott McClellan

In my talks with President Aristide on board the plane Monday, I asked him if he had resigned— as the Bush administration continues to allege.

PRESIDENT ARISTIDE: No, I didn’t resign. What some people call “resignation” is a “new coup d’etat,” or “modern kidnapping.”

Because the circumstances under which Aristide was removed from Haiti continue to be a source of great international controversy, we felt we needed to get as comprehensive a version of events as possible from President Aristide. I asked him why he calls his removal from Haiti a coup and a kidnapping.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: When the reporters brought the question to the Pentagon, they questioned Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and asked if it was true what Pacifica was reporting. Donald Rumsfeld:

DONALD RUMSFELD: The idea that someone was abducted is just totally inconsistent with everything I heard or saw or am aware of. So I think that — that I do not believe he is saying what you say — are saying he is saying.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. Here is Secretary of State Colin Powell speaking on March 1 of last year.

COLIN POWELL: He was not kidnapped. We did not force him onto the airplane. He went onto the airplane willingly, and that’s the truth.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, White House Press Secretary, Scott McClellan.

SCOTT McCLELLAN: Conspiracy theories like that do nothing to help the Haitian people realize the future that they aspire to, which is a better future, a more free future and a more prosperous future. We took steps to protect Mr. Aristide. We took steps to protect his family as they departed Haiti. It was Mr. Aristide’s decision to resign, and he spelled out his reasons why.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Scott McClellan. Because this issue of the circumstances under which Aristide was removed from Haiti continues to be a source of great international controversy, we felt we needed to get as comprehensive a version of events as possible from President Aristide. In a moment, we’ll hear from Franz Gabriel, Aristide’s personal bodyguard, who was with him in the palace in the night of February 28-29 and was also taken to the Central African Republic. But first we are going to begin with President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. I talked to him after a U.S. delegation led by U.S. Congress member Maxine Waters, the founder of TransAfrica, Randall Robinson, a member of the Jamaican parliament Sharon Hay Webster, Aristide’s attorney Ira Kurzban chartered a small plane and traveled to the Central African Republic to retrieve the Aristides in the second week of March 2004. I traveled as the only broadcast journalist to document this trip with Peter Eisner of The Washington Post. We went from Miami through Barbados to Dakar, Senegal, to the Central African Republic. There, the delegation negotiated with the dictator of the Central African Republic, Bozize, for many hours through the night. As Bozize would go away to consider the request to free the Aristides, President Aristide told me he was actually going to get his marching orders from the U.S. and France, that the dictator was. Finally, the dictator said that the Aristides could leave. The small delegation had called the bluff of the most powerful country on earth and said, if the Aristides had gone freely, they should be able to leave freely. And so, they made their way back and as we were traveling from Dakar, Senegal, to the Cape Verde islands, then flew over the Atlantic, President Aristide described what had happened to him two weeks before, the night of February 28, the morning of February 29. This is president Aristide’s version of what took place one year ago today.

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: They broke the constitutional order by using force to have me out of the country the way it happened.

AMY GOODMAN: How did it happen?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: I will not go into details, maybe next time. But as I said, they used force. When you have militaries coming from abroad, surrounding your house, taking control of the airport, surrounding the national palace, being in the streets, and taking you from your house to put you in a plane where you have to spend 20 hours without knowing where they were going to go with you, without talking about details, which I already did somehow on other occasions, it was using force to take an elected president out of his country.

AMY GOODMAN: And was that U.S. military that took you out?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: There were U.S. military, and I suspect it could be also completed with the presence of other militaries from other countries.

AMY GOODMAN: When they came to your house, in the early morning of February 29, was it U.S. military that came?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: There were diplomats. There were U.S. military. There were U.S. people.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did they tell you?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: Well, as I said, I prefer to not go into details right now, because I have already talked about in in details on other occasions, and it’s also one good opportunity for me to help the people focusing on the results of that kidnapping, because actually, they still continue to kill Haitians in Haiti, and Haitians continue to flee Haiti by boat people. Others have to go to hiding. Others courageously went to the streets to demonstrate in a peaceful way, asking for my return, and when we know what happened to those they killed, we have concerns about what may happen to those who peacefully demonstrate for my return.

AMY GOODMAN: The Bush administration said that when you — after you got on the plane, when you were leaving, you spoke with CARICOM leaders. Is this true?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: They lied. I never had any opportunity from February 28 at night, when they started, to the minute I arrived in car, I never had any conversation with anyone from CARICOM within that frame of time.

AMY GOODMAN: How many U.S. military were on the plane with you?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: I cannot know how many were there, but I know it is the plane with 55 seats. Among them we had 19 American agents from Steele Foundation, which is a U.S. company providing security to the President and First Lady, V.I.P. people, based on an agreement which was signed between the government of Haiti and that U.S. company called Steele Foundation. So, they put those 19 American agents in that plane, and there were five, my side — there were two Haitian ladies, wives of two American agents, plus a baby, one year and a half. The rest, they were American militaries.

AMY GOODMAN: Were they dressed in military uniform?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: There were not only dressed in — with their uniform, it was like if they were going to war. For the first period of time on the ground, when we went to the plane, after the plane took off, that’s the way they were. Then they changed, moving from the uniform to other kind of clothes.

AMY GOODMAN: Civilian clothing?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And did they go with you all the way to the Central African Republic?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: They did, without telling me where they were taking me, without telling me how long it would take us to be there. And the most cynical happened with that baby, one year-and-a-half old, because when they wanted — when the father wanted to get outwith him, based on what I heard, they told him no. So that little baby had to spend all this time sitting in the military plane, arriving in the car. He and his father had to go back with the same plane. So, only God knows the kind of suffering he went through.

AMY GOODMAN: Did these people ever get off the plane in the Central African Republic, all the military and security?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: I cannot tell you, because once I got out of the plane, I was well received by five members — five ministers of the government of President Francois Bozize. So being with them at that time, I don’t know how they managed after I left.

AMY GOODMAN: Did the Stele Foundation bring in reinforcements when the situation got more dangerous?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: No. because Saturday night, when they came to me, they told me: (a), the U.S. officials ordered them to leave and to leave immediately; (b), the 25 American agents they were supposed to welcome the day after, February 29, to reinforce the team, couldn’t leave the U.S. to join them in Haiti. So, that was a very strong message to them and to us.

AMY GOODMAN: Could you repeat that? What were the regulations?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: Please, I don’t get the question?

AMY GOODMAN: Could you repeat that? What happened — what happened with the Steele Foundation employees? What you just said about the reinforcements.

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: I said that Saturday, 29 — 28 at night, when they came to me, they told me that: (a) they ordered them to leave, and immediately, (b), the day after, February 29, they were supposed to welcome another team of 25 American agents to reinforce them on the ground, and U.S. officials prevented those 25 to leave the United States to go to Haiti to join them.

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s what the Steele Foundation told you?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: Did they say why the U.S. said that?

JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE: Well, I didn’t go into details with them, but it was obvious in my mind, that was part of the global plan. The global plan was to kidnap me through a coup d’etat. Of course, that represented one piece of the picture.

AMY GOODMAN: Jean-Bertrand Aristide describing the events of February 28-29, 2004, when he says he was overthrown in a U.S. coup. We spoke in a plane going over the Atlantic, coming back from the Central African Republic. But while there, I had a chance to speak with another person who witnessed firsthand the events of that night. He is Franz Gabriel, Aristide’s personal bodyguard. I spoke with him inside the presidential palace in Bengi as President Aristide was meeting with the president of the Central African Republic, General Francois Bozize. He provided further details on the role of the United States in Arisitide’s removal, in particular the role of the deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Haiti, Luis Moreno. Peter Eisner of The Washington Post was also in the room. During the interview, Gabriel’s mobile telephone rang many times. I began by asking him to describe his last night in Haiti.

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well I was at the house at 5:00 a.m., when I saw some U.S. personnel from the Embassy, of which I recognized Mr. Moreno. They came in to tell the president that they were going to organize a press conference at the Embassy, and for him to be ready to accompany them. The president called Mildred, and we boarded the vehicles to go to the Embassy, and as we were heading towards the Embassy, you know, passing by the airport, we ended up making a right inside the airport, and that’s when I realized that we were not going to the Embassy.

PETER EISNER: And the president also didn’t know that — he also thought he was going to a press conference at the Embassy?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Yes. That’s what Mr. Moreno had invited him to do. And as we were at the end of the runway’s threshold, we saw a plane pull in, and just parked there. And then we saw some military personnel.

AMY GOODMAN: What was the press conference supposed to be about?

FRANZ GABRIEL: The press conference was probably going to be about his leaving of power.

AMY GOODMAN: Whether he would leave power?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Whether he would leave power, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: So what happened when you saw the plane? What happened next?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well, I saw a deployment of U.S. Marines everywhere. And that’s when I realized that, you know, it was something serious. I saw a white plane with a U.S. flag at the tail of the aircraft, and it looked strange because there was no markings on it. And as the plane stopped, they had us board. Everybody boarded the plane. And all the Steele Foundation agents that were on contract with the government to give the president security, boarded the plane also.

AMY GOODMAN: Are you with Steele Foundation?

FRANZ GABRIEL: I’m not with Steele, I’m with President Aristide. And we all boarded the plane. They sat us down. They didn’t tell us where we were going. And then they closed the door, didn’t even want us to pull the shades up. And nothing. We just sat there and waited. They sat us down and then we just — they closed up the gate of the plane, and then we took off.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you know where you were going?

FRANZ GABRIEL: No, we never knew where we were going.

AMY GOODMAN: For how long?

FRANZ GABRIEL: When we landed in Antigua, that’s what they told us, we landed in Antigua. And in Antigua, we — they told us that there is a possibility that we might be going to South Africa. But he was talking — I mean, the person that was relating the information was relating it to one of the Steele Foundation agents. And I overheard it when he said it. As we were sitting down, they started taking our names down. And they asked the Steele Foundation people, you know, where they were going.

PETER EISNER: Who is “they?”

FRANZ GABRIEL: The guys that were part of the crew of the airplane.

PETER EISNER: They didn’t identify themselves? They were military —- do you know if they were military -—?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well, they boarded the plane dressed as military. But as soon as they boarded the plane, they changed clothes to civilian. They were, you know, they had baseball hats and regular civilian clothes. So they no longer appeared as military.

AMY GOODMAN: And they were who, these people that changed their clothes?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well, they boarded the plane. You know, they were dressed in full military gear.

AMY GOODMAN: U.S. Military?

FRANZ GABRIEL: U.S. Military.

AMY GOODMAN: And so you left Antigua, overhearing that you might be going to South Africa, but not knowing.

FRANZ GABRIEL: Yes. I left Antigua thinking that we might be going to South Africa because that’s what they said. As we were on the plane, we landed in an island called Asuncion. Asuncion, and that’s when they told us that South Africa would not accept us and that they didn’t know where we were going because they didn’t have a country that would accept us at this time. So, therefore…

AMY GOODMAN: Had the president applied to these countries?

FRANZ GABRIEL: The president didn’t even know where he was going.

AMY GOODMAN: Franz Gabriel, the security advisor, bodyguard of President Aristide, speaking in the palace at the Central African Republic on March 14, 2004, two weeks after the ouster of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. When we come back, I ask Franz Gabriel if he thinks this was a kidnapping, as President Aristide has described it. We’ll be back with that response, then we’ll talk about the privatization of intelligence in Iraq. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: On this first anniversary of the ouster of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, we return now to the interview with President Aristide’s personal bodyguard, Franz Gabriel, done in the Central African Republic just after Aristide was ousted and sent there on a U.S. plane. I ask Gabriel if he agreed that Aristide had been kidnapped.

FRANZ GABRIEL: I would say so. I would say that it is a kidnapping.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you have — you talked about the U.S. presence at the airport taking him to the airport. What were the other evidences of U.S. involvement? What was the other evidence of U.S. involvement?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well, a plane that shows up at quarter to six in the morning, out of nowhere. You know, the tower is not even open. There’s a big flag in the middle of the vertical fin, a big U.S. flag in the middle of the vertical fin. A big plane, you know, coming in at quarter to six in the morning shows that, you know, there’s some kind of involvement.

AMY GOODMAN: How many U.S. military left with you on the plane?

FRANZ GABRIEL: 20.

AMY GOODMAN: And how many security from Steele Foundation?

FRANZ GABRIEL: About 18.

AMY GOODMAN: And were they all U.S.?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was 38 U.S. security and military?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Mm-hmm. And there’s — some Steele guys had their wives with them, and a baby that was probably a year old.

AMY GOODMAN: So they had to figure this out very fast if they wanted to get to the airport and get their families to the airport. How did they get their families to the airport?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Well, it happened very fast, because somehow between the U.S. Embassy and some of the Steele guys, there was some communication.

AMY GOODMAN: So they knew before the president, that the president was being taken to the airport?

FRANZ GABRIEL: Yes. That is the only thing I can…

AMY GOODMAN: And what happened to everyone? Did they all come here?

FRANZ GABRIEL: They all came here and left. None of them disembarked the plane.

AMY GOODMAN: Franz Gabriel, the personal security advisor of President Aristide in the Central African Republic last March 14, two weeks after Aristide’s ouster. Aristide was brought back to Jamaica, with his wife, the first lady of Haiti, Mildred Aristide, and then ultimately, they and their children went to South Africa, where they are today. President Aristide now is saying that he does remain the President of Haiti and is confident that he will one day return to his homeland. If you want to see all our coverage in those last days and the days after the coup in Haiti, you can go to democracynow.org.

Media Options