Topics

Guests

- Howard Zinnlegendary historian, author, professor, playwright and activist. His classic book is A People’s History of the United States.

We speak with legendary historian Howard Zinn, author of one of the most popular books on American History, “A People’s History of the United States.” In his youth, Zinn was a bombardier in World War II and participated in the Napalm bombing in France. He went on to dedicate his life to opposing wars of all kind. He was an active fighter in Civil Rights Movement and served as an advisor to the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. In the late 1960s, he traveled to Vietnam with Father Dan Berrigan during intensive US attacks and negotiated the release of US POWs. In fact, Howard Zinn was a part of most struggles for social justice in this country during his lifetime. He joins us in our firehouse studio. [includes rush transcript]

Following his life is like taking a journey through the major struggles of the 20th Century. We spend the rest of the hour with the legendary historian Howard Zinn. In his youth, he was a bombardier in WWII and participated in the Napalm bombing in France. He went on to dedicate his life to opposing wars of all kind. He was an active fighter in Civil Rights Movement and served as an advisor to the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. In the late 1960s, he traveled to Vietnam with Father Dan Berrigan during intensive US attacks and negotiated the release of US POWs. In fact, Howard Zinn was a part of most struggles for social justice in this country during his lifetime. He was a professor for seven years at the historically black college for women, Spelman College. Eventually he was fired for insubordination. He is a historian and the author of one of the most popular books on American History, “A People’s History of the United States.”

But before we go to him, we are going to go to an excerpt of a new film that chronicles his life. It is titled, “You can’t be Neutral on a Moving Train” which is the title of his autobiography. The film is produced by First Run Features and is narrated by Zinn’s next-door neighbor, actor Matt Damon.

- “You can’t be Neutral on a Moving Train,” documentary produced by First Run Features.

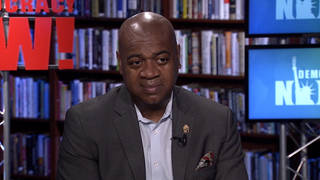

- Howard Zinn, joins us in our firehouse studio.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: He is an historian and author of one of the most popular books on American history, A People’s History of the United States. But before we go to him, we’re turning to an excerpt of a new film that chronicles his life. It’s titled, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, which is also the title of his autobiography. The film is produced by First Run Features. It’s narrated by Howard Zinn’s next door neighbor, actor Matt Damon.

HOWARD ZINN: We grow up in a controlled society. And so we thought, if one person kills another person, that is murder. But if the government kills 100,000 persons, that is patriotism. And they’ll say we’re disturbing the peace, but there is no peace. What really bothers them is that we’re disturbing the war.

MATT DAMON: [from The Zinn ReaderI start from the supposition that the world is topsy turvy, that things are all wrong, that the wrong people are in jail, and the wrong people are out of jail, that the wrong people are in power, and the wrong people are out of power. I start from the supposition that we don’t have to say too much about this, because all we have to do is think about the state of the world today and realize that things are all upside-down.

HOWARD ZINN: History is important. If you don’t know history, it’s as if you were born yesterday. And if you were born yesterday, anybody up there in a position of power can tell you anything, and you have no way of checking up on it.

HOWARD ZINN: It’s exactly when you’re in the midst of a war or about to go into a war that you need your freedom of speech. Lives are at stake. If you are put in fear of speaking out, then democracy has been severely crippled.

FRIEND: When you think of people like Howard, you think of the person who really stands up to authority and understands radicalism in its basic meaning, that is, going to go the root of problems and demanding that those problems be confronted.

FRIEND: A life of political engagement is so much more interesting and so much more joyful and comradely than a life of private disengagement and private consumption.

HOWARD ZINN: I don’t believe it’s possible to be neutral. The world is already moving in certain directions. And to be neutral, to be passive in a situation like that is to collaborate with whatever is going on. And I, as a teacher, do not want to be a collaborator with whatever is happening in the world. I want myself, as a teacher, and I want you as students, to intercede with whatever is happening in the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Howard Zinn, from the new film about his life called, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, the same title as his autobiography. And he joins us in the studio today. Welcome to Democracy Now!

HOWARD ZINN: Thank you, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: It is great to have you with us.

HOWARD ZINN: Well, it’s nice of you to invite me. I was worried.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you just came from Bedford Hills Correctional Facility?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, actually, yesterday afternoon I spoke at the Bedford Hills, euphemistically called, Correctional Facility — they hardly correct anything, but — spoke to prisoners there, women prisoners, mostly prisoners of color. I spoke to them yesterday afternoon before I gave this talk last night at Manhattanville College.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did you talk about with the women?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, they had been using my book. They have classes. They’re using my book, A People’s History of the United States. And I talked to them about history, about doing history, about why I did history the way I did, why I did unneutral history and how I came to do it. And I told them something about my life, and, of course, I always like to talk about that, you know.

And then they asked a lot of questions, a very lively, enthusiastic, excited group. I mean, if every teacher in the country had a class like that, you know, they would be inspired. And it’s wonderful — and I’ve always found this to be true — wonderful and always amazing when you talk to prisoners, who should be the last ones to be up and optimistic and in good spirits, but it’s always there. It’s actually encouraging, you know, and, of course, troubling to know that these people, these remarkable people, are being kept in prison, you know, very often, most of the time, for nonviolent crimes, and kept there for long periods of time. It’s a sort of sad commentary on American society that we have people in Washington who are free, and these people are in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Howard Zinn, we have to break and then we’re going to come back to the legendary historian to continue on this hour.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: I’m Amy Goodman here with historian Howard Zinn. He has written many books, among them People’s History of the United States, and one of his most recent is now a companion volume called Voices of a People’s History of the United States. You talked about being a teacher, but, Howard Zinn, the places you were — where you did teach — well, Spelman, you were fired, and Boston University, you were almost fired.

HOWARD ZINN: Oh, are you trying to make me out as a troublemaker?

AMY GOODMAN: What happened to you at Spelman?

HOWARD ZINN: At Spelman, I got involved with my students in the actions that were going on in the South, the sit-ins, the demonstrations, the picket lines. I was supporting my students. And this was the first Black president of Spelman College, a very conservative institution. He wasn’t happy about me joining the students in all of these things, wasn’t happy about a lot of things that they did. But he couldn’t do anything about it. But when I — the students came back from, you might say, from jail and then rebelled against the campus regulations and the restrictions on them, and I supported them, that was too much.

AMY GOODMAN: During the civil rights years?

HOWARD ZINN: This was — yeah, these were during the civil rights years. And so, you know, he was very unhappy with the fact that I was supporting the students who were rebelling against the paternalism and the authoritarianism on that campus.

AMY GOODMAN: They were women students?

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah, these were Black women students. And, you know, the movement brought them out of this little sort of convent-like atmosphere of Spelman College and out into the world.

AMY GOODMAN: The author Alice Walker was one of those students?

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah, Alice Walker was one of my students. Marian Wright Edelman, the head of the Children’s Defense Fund now in Washington, she was one of my students. I’m very proud of those students I had at Spelman. And yeah, Marian Wright Edelman was in jail, and Alice Walker was in jail. And yeah, it was a great moment.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Boston University was many years later. Why did you almost get thrown out of there?

HOWARD ZINN: Why did I almost get thrown out of Boston University? We had a strike. Faculty went on strike. Secretaries went on strike. They settled with the faculty after what was a successful strike, but not with the secretaries. And so, I and some other faculty refused to cross the secretaries’ picket line. And five of us who refused to do that were threatened with firing, even though all of us had tenure. And so it was a long struggle, but we won.

AMY GOODMAN: Going back before both of your tenures as professor, you were a bombardier in World War II.

HOWARD ZINN: That’s true, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And you talk about your final bombing run, not over Japan, not over Germany, but over France.

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah. Well, we thought our bombing missions were over. The war was about to come to an end. This was in April of 1945. You may remember the war ended in early May 1945. This was a few weeks before the war was going to be over, and everybody knew it was going to be over, and our armies were past France into Germany, but there was a little pocket of German soldiers hanging around this little town of Royan on the Atlantic coast of France, and the Air Force decided to bomb them — 1,200 heavy bombers, and I was in one of them, flew over this little town of Royan and dropped napalm — first use of napalm in the European theater.

And we don’t know how many people we killed, how many people were terribly burned as a result of what we did. But I did it, like most soldiers do, unthinkingly, mechanically, thinking we’re on the right side, they’re on the wrong side, and therefore we can do whatever we want, and it’s OK. And only afterward, only really after the war, did I — when I was reading about Hiroshima from John Hersey and reading the stories of the survivors of Hiroshima and what they went through, only then did I begin to think about the human effects of bombing. Only then did I begin to think about what it meant to human beings on the ground when bombs were dropped on them, because as a bombardier, I was flying at 30,000 feet, six miles high, couldn’t hear screams, couldn’t see blood. And this is modern warfare.

In modern warfare, soldiers fire, they drop bombs, and they have no notion, really, of what is happening to the human beings that they’re firing on. Everything is done at a distance. This enables terrible atrocities to take place. And I think, reflecting back on that bombing raid, and thinking of that in Hiroshima and all the other raids on civilian cities and the killing of huge numbers of civilians in German and Japanese cities, the killing of 100,000 people in Tokyo in one night of firebombing, all of that made me realize war, even so-called good wars against fascism, like World War II, wars don’t solve any fundamental problems, and they always poison everybody on both sides. They poison the minds and souls of everybody on both sides. We’re seeing that now in Iraq, where the minds of our soldiers are being poisoned by being an occupying army in a land where they are not wanted. And the results are terrible.

AMY GOODMAN: You learned you dropped napalm on this French village?

HOWARD ZINN: You say?

AMY GOODMAN: Napalm?

HOWARD ZINN: Napalm. Well, we didn’t — actually didn’t know what it was. They said, “Oh, you’re not going to have the usually 500-pound demolition bombs. You’re going to carry one — you’re going to carry 30 100-pound canisters of jellied gasoline.” We had no idea what that was, but it was napalm.

AMY GOODMAN: You went to that village later?

HOWARD ZINN: Later, I went, yeah. Later, I visited that village, about 10 years after the war. And I went to the library, which had been destroyed and which was now rebuilt, and I dug out records of the survivors and what they had written about the bombing. And I wrote a kind of essay about the bombing of Royan, which appears — where does it appear? — it appears in my book The Zinn Reader and also in my book The Politics of History. But it was — for me, it was a very important experience, a very great sobering lesson about so-called good wars.

AMY GOODMAN: You learned when you were there on the ground many years later who had died?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, I — you know, I spoke to people who had survived that and whose family members had died. And they were very bitter about the bombing. And, you know, they attributed it to all sorts of things, the desire to try out a new weapon. It’s amazing how many things are done in a war just to try out new weapons. You know, maybe one of the reasons for dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were to see what this does to human beings. Human beings become sacrifices in the desire to develop new military technology. And I think that was one of those instances.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to historian Howard Zinn, here in our firehouse studio in Chinatown, just blocks from where the towers of the World Trade Center once stood. You went to Vietnam, to North Vietnam, with Dan Berrigan?

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Why?

HOWARD ZINN: Why? Well, this was early 1968. This was the time of the Tet Offensive, also the time of the Tet holiday, the Vietnamese holiday. And the North Vietnamese decided they wanted to release the first three airmen prisoners who had been shot down over North Vietnam. And they wanted to release them in the custody of not the American government, but the peace movement. So Daniel Berrigan, poet, priest, whom I had never met before, he and I traveled together to Hanoi, to North Vietnam, to pick up these three American airmen who were being released by the North Vietnamese.

And then we spent some time in Hanoi and in the surrounding area, visited bombed-out areas, visited little villages that had been jet bombed in the middle of the night, a million miles from any possible military target. And that — we were being bombed — Vietnam was being bombed every night. Every day we were going into air raid shelters. Every night Daniel Berrigan would write a poem about what had happened that day. And, you know —

AMY GOODMAN: What do you say to those, then and now, before the invasion, who would go to Iraq, those who went to North Vietnam, when they would be called traitors, giving comfort to the enemy?

HOWARD ZINN: You mean Americans who went to North Vietnam? You mean like Jane Fonda and so many others who went to North Vietnam?

AMY GOODMAN: And Iraq before. I mean even people like Congress member McDermott of Seattle, reporters saying that they should resign.

HOWARD ZINN: Oh, people have gone to Iraq. And, I mean, what about — you know, there’s people in Voices in the Wilderness, Americans who went to Iraq and violating the U.S. sanctions, bringing food and medicine, you know. And the whole business of being traitors, you know, I think there’s a whole — there’s somehow some wrongheaded notion of what treason is and what patriotism is, and there’s some notion that if you disobey the orders of your government or the laws of your government, you’re being treasonous. But I believe the government is being treasonous and the government is being unpatriotic when the government violates the fundamental rights of human beings, when the government invades another country, a country that has not attacked it, a country that has not threatened it. When our government invades another country and drops bombs and kills huge numbers of people, and then Americans have the guts to go to that country and bring people food and medicine or go to see what is going on, as many Americans did when they went to Vietnam, I think these are the most patriotic Americans.

And, you know, if you define patriotism as obedience to the government, then you are, I think, following a kind of totalitarian principle, because that’s the principle of a totalitarian state, that you do what the government tells you to do. And democracy means that the government is an instrument of the people. This is the Declaration of Independence. Governments are artificial entities set up in order to preserve the rights, equal right to life, liberty, pursuit of happiness of people. When the government violates those rights, it is the duty of people to defy that government. That is patriotism.

AMY GOODMAN: Howard Zinn, you called your autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train. Why?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, it came from — I stole it from myself. That is, I used to say that to my classes at the beginning of every class. I wanted to be honest with them about the fact that they were not entering a class where the teacher would be neutral. It was not going to be a class where the teacher spent a half a year or year with the students, and they would have no idea where the teacher stood on the important issues. This is not going to be a neutral class, I said. I don’t believe in neutrality. I believe neutrality is impossible, because the world is already moving in certain directions. Wars are going on. Children are starving. And to be neutral, to pretend to neutrality, to not take a stand in a situation like that, is to collaborate with whatever is going on, to allow it to happen. I did not want to be a collaborator with what was happening. I wanted to enter into history. I wanted to play a role. I wanted my students to play a role. I wanted us to intercede. I wanted my history to intercede and to take a stand on behalf of peace, on behalf of a racial equality or sexual equality. And so I wanted my students to know that right from the beginning, know you can’t be neutral on a moving train.

AMY GOODMAN: Were your surprised by the election of President Bush, November 2004?

HOWARD ZINN: A little. A little. That is, I thought that maybe by then, perhaps there would be enough understanding about the deception, the hypocrisy of the US government, just enough to dethrone Bush, but I say only a little surprised, because on the other hand, I knew that John Kerry was not the candidate to represent the feelings of the American people. By then, by the time of the election, at least half of the American people were already against the war. Now they faced an election where 100% of the candidates were for the war. So, they had nobody to vote for. And so I — with nobody to vote for, with no real alternative, of course, 40% of the voting population did not vote. And people ought to remember this. You know, Bush did not win overwhelmingly. You know, he won by one or two percentage points. And if you consider how many people voted for him against the voting population, you know, he got, you know, maybe 30% of the voting population. But it was a commentary on the pitiful showing of the Democratic Party, its failure to be a true opposition party in this country, and I think maybe a wake-up call to Americans to try to create a new political alternative to a political system that is really a one-party system, and it is quite corrupt.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see that movement developing now? Outside of the two parties?

HOWARD ZINN: I hope so.

AMY GOODMAN: Or within one of the parties?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, there is some movement within the Democratic Party. And I think it will take work within and work without. That is, it will take people in the Democratic Party to demand a change in the Democratic Party. I notice that the Democratic Party in California has just had a convention in which they voted for the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq. And this is a good sign, and if Democratic Party groups around the country would demand that the National Democratic Party call for an end to this war and an end to the occupation, that would be a sign that the Democratic Party is changing and moving in the right direction. But it will not do that, I think, unless there are groups outside of the Democratic Party that create a movement that puts pressure on the Democratic Party.

AMY GOODMAN: Last question, Howard Zinn, you’re going back to Spelman College to give the commencement address and receive an honorary degree from the school you were fired from.

HOWARD ZINN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: On May 15.

HOWARD ZINN: Yeah. It’s — 40 years after I was fired, I am invited back. Well, there’s a new president, a very progressive African American woman, Beverly Tatum, a scholar of race relations in this country, and she sent me an invitation to give me an honorary degree and to deliver the commencement address, and she wrote at the bottom of her letter, “It’s about time.” That was nice.

AMY GOODMAN: You feel vindicated?

HOWARD ZINN: Well, I felt vindicated one minute after I was fired. But this is good. It’s a good feeling, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You have your first sentence prepared, what you are going to say as you return to this college?

HOWARD ZINN: Oh, you have made me realize I should prepare my first sentence. I’m working on it. I’ll spend a few days working on my first sentence.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much for joining us. Howard Zinn, among many other accomplishments, is 82 years old.

HOWARD ZINN: You consider that an accomplishment?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, sure. I just saw a friend who said she celebrated her 106th birthday with her grandmother, and her grandmother said to her, “Oh, to be 100 again.” Looking forward to the next decades with you, Howard Zinn.

HOWARD ZINN: Thanks, Amy.

Media Options