Topics

New Orleans judge Arthur Hunter has pledged to begin releasing prisoners today whose cases have been delayed since Hurricane Katrina. Many prisoners jailed in New Orleans for over a year haven’t talked to a lawyer or had a day in court. Some have yet to be charged with a crime. We speak with Katherine Mattes of Tulane University’s Criminal Law Clinic. [includes rush transcript]

We take a look at the breakdown in the New Orleans criminal justice system. A New Orleans judge has pledged to begin releasing prisoners today whose cases have been delayed since Hurricane Katrina.

Many prisoners jailed in New Orleans for over a year haven’t talked to a lawyer or had a day in court. Some have yet to be charged with a crime. Judge Arthur Hunter announced last month he will begin reviewing prisoners today on a case-by-case basis. Arthur said, “It’s something the entire country should be concerned about…If we’re still part of the United States, and the Constitution still means something, why is the New Orleans criminal justice system still in shambles?”

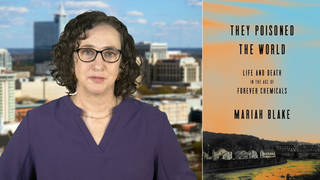

- Katherine Mattes, law professor at Tulane University and the deputy director of the university’s Criminal Law Clinic.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re also joined today by a law professor, as we look at the criminal justice system, also joining us from public television station WLAE in New Orleans. A New Orleans judge has pledged to begin releasing prisoners today, whose cases have been delayed since Hurricane Katrina. Many prisoners jailed in New Orleans for over a year haven’t talked to a lawyer or had a day in court. Some have yet to be charged with a crime. Judge Arthur Hunter announced last month he’ll begin reviewing prisoners today on a case-by-case basis. Judge Arthur said, quote, “It’s something the entire country should be concerned about…If we’re still part of the United States and the Constitution still means something, why is the New Orleans criminal justice system still in shambles?” That’s the question of the judge.

Well, Katherine Mattes joins us now from New Orleans. She’s a law professor at Tulane University and deputy director of the university’s Criminal Law Clinic. What is the state of the criminal justice system in New Orleans right now, Professor Mattes?

KATHERINE MATTES: Good morning, Amy. Unfortunately, the devastation that occurred that devastated the criminal justice system at Katrina is continued to this day. We have, as you mentioned and as Judge Hunter identified, we have people who have been in custody before Katrina and remain in custody and have to this day never spoken to a lawyer, have never been in court. What happened is we had a system that was, prior to Katrina, a system that was barely functioning. And when Katrina hit, all the systems that composed the criminal justice system — the sheriffs, the district attorneys, the courts, the public defenders — all those systems failed, and that failure continues today.

Unfortunately, during the hurricane, the inmates of the prison system here in New Orleans were not evacuated. They remained in custody at the jails in the central city part of New Orleans, which was flooded. The conditions that they remained in were horrendous. When they finally were evacuated, they were evacuated throughout the state. Those inmates remain throughout the state. When they were evacuated, their records were not taken with them. They were taken to different facilities throughout the state, Department of Correction facilities, as well as local parish facilities, local jails and their — who they were, where they were, what charges they were being held on, all that information was lost. It was not transported with them.

So, unfortunately, what’s happened is those people still remain out throughout the state of Louisiana, and we are still finding people every day who have not yet been to court, who have no lawyer representing them, whose interests have not been protected. They have been through horrendous experiences, both in the evacuation — they have no idea where their families are, many of them. Their families don’t know where they are. And what’s unfortunate is, a year later, this situation still exists.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the number of public defenders?

KATHERINE MATTES: Well, what you have to understand is, pre-Katrina the public defenders system was inadequate. We had a system of approximately 42 public defenders, who are part-time public defenders. They were funded largely from funds that were assessed from convictions, particularly traffic convictions. Judge Hunter, as well as Judge Johnson, have ruled that the statute that provided that funding is an unconstitutional statute. That case and that situation still has to be presented before the Supreme Court. But what happened was, once again, the funding was, if you were arrested and you were convicted or pled guilty to a charge, you were assessed a fee. And that fee then funded the public defenders’ office. The majority of those fees came from traffic tickets. And, of course, after Katrina, there were no traffic tickets, so there was no money.

And so, the public defenders’ office went from an office of approximately 42 part-time public defenders to an office of four. You’re talking about an office of four lawyers, who in theory represent all the indigent criminal defendants in Orleans Parish. And that number, the number of people in the jail, when it was evacuated, was approximately 6,500 people. So you’re talking about four attorneys who are representing 6,500 people. And what was particularly distressing is, because the public defenders’ office prior to Katrina was poorly organized, poorly staffed, inadequately staffed — they didn’t have enough lawyers doing enough full-time work — but also they had no system to know who their clients were, who they represented.

So when these people were disbursed throughout the state of Louisiana, there was no one to say, “Ah, you know, this is my list of clients. This is the office’s list of clients. Let’s find out where these people are. Let’s find out if they don’t belong in jail, if their sentences are over, or if they have served more time than the maximum sentence for the charge they were arrested, let’s make sure that they are released.” And that never happened. Currently what’s — the public defenders’ office has gotten some funding, and they have hired more public defenders, but they are still far below, far below, the levels of representation that’s required to serve the people who are in custody today.

AMY GOODMAN: Katherine Mattes, I want to thank you for joining us, law professor at Tulane, and Tracie Washington, for joining us, as well, a longtime New Orleans resident and civil rights attorney, director of the NAACP Gulf Coast Advocacy Center. As we end with the words of a person who had to flee, because of Hurricane Katrina — not New Orleans, but Mobile, Alabama — and she hasn’t been able to return. Her name is Joetta Rogers. She spoke out last night in New York.

JOETTA ROGERS: I spent two days standing in Salvation Army waiting area in Mobile, Alabama, begging and pleading for some help, and was confronted by a social worker with an attitude problem toward those of us in need, and she made us suffer by handling and treating us like we were poison and contagious or nothing.

And then, I went to Red Cross for assistance and had them to tell me that because of the zip code that I lived in, and there were only houses in my area that sustained severe damage, they could not help me.

Then I came to New York with only a dollar and 55 cents in my pocket, after riding 32 hours on a bus and being stuck at Port Authority for seven hours and having a Red Cross worker tell me that she wanted me to walk from 42nd and 8th Avenue to 66th and Amsterdam for some help.

And sixth, and my final thing was, from November 'til May, it took me just that long, talking to about 200 FEMA operators to get okayed for room assistance. And I want you to know something about the FEMA operators on their [inaudible], they are the most rudest people. They talk to us like we dogs. You understand? They talk to us like that's their money. Now, I want to tell you something. I’m mad. And the reason why I’m mad, and I’m really, really ready to fight is because, why should I have to go back to FEMA and ask them —

AMY GOODMAN: The words of Joetta Rogers. She couldn’t return yet to her home.

Media Options