Guests

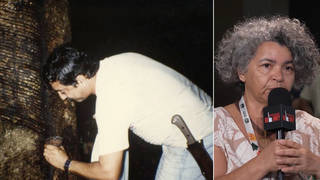

- Kathy Kellyexecutive director of Voices for Creative Nonviolence. She is a veteran peace activist who has worked extensively with Iraqi refugees in Amman, Jordan.

- David Smith-Ferripoet and peace activist. His latest collection of poetry is titled Battlefield Without Borders.

As the United Nations reveals that 2,000 Iraqis are still fleeing their homes each day because of the continuing violence, peace activists Kathy Kelly and David Smith-Ferri join us to talk about their work with Iraq’s displaced. Kathy Kelly is the executive director of Voices for Creative Nonviolence and founder of Voices in the Wilderness. David Smith-Ferri is a poet and peace activist. His latest collection of poetry is titled “Battlefield Without Borders.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The United Nations revealed this week that 2,000 Iraqis are still fleeing their homes each day because of the continuing violence. The U.N. refugee agency estimates that over 4.4 million Iraqis have been displaced. Some groups put the estimate even higher. More than 2.2 million of the Iraqi refugees are living in Syria and Jordan. The U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq has created the largest refugee crisis in the Middle East since the creation of Israel in 1948, when more than half the Palestinian population was driven off of their homeland.

We end today’s show with two peace activists who have spent time in Jordan working with Iraqi refugees. Kathy Kelly is the executive director of Voices for Creative Nonviolence. She is a veteran peace activist and the founder of Voices in the Wilderness. Earlier this year she also helped organize the Occupation Project to oppose continued funding of the Iraq war. David Smith-Ferri is a poet and peace activist. His latest collection of poetry is titled Battlefield Without Borders.

Kathy Kelly and David Smith-Ferri are in New York as part of a speaking tour. Welcome, both of you, to Democracy Now!

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: Thank you.

KATHY KELLY: Thank you, Juan.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Kathy, talk to us about the refugee crisis. Recently, the Syrian government tried to close the border, at least in terms of folks coming in and out of that country. Could you talk to us on what’s going on with the Iraqi refugees?

KATHY KELLY: Certainly people that feel they have no choice but to flee are caught literally trapped, and I think we can understand why neighboring countries might be saying, “Look, we didn’t start this war. This was a war of choice that the United States waged. And what responsibility do U.S. people have to bear some of the consequence?” I think it’s understandable, and yet there is a humanitarian catastrophe, and it ought to be labeled as nothing less than that and dealt with by, I believe, the United Nations and other countries, but the United States has a huge responsibility to contribute financial reparation for the suffering caused. And yet, we see the United States government repeatedly saying we’re not going to engage in negotiation, we’re not going to engage in dialogue, and we’re not going to help the people who have fled from the crisis that we’ve caused.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: So how are the governments in Jordan and Syria and other countries — how are they financing whatever work they do with the refugees?

KATHY KELLY: Well, in Jordan, Jordan is an ally of the United States, and there has been some aid that has come, to the extent that the king of Jordan said that for the first time in three years children, Iraqi children, living in Jordan could start to enter into the school system. There is some U.N. aid that comes through the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, but there’s nothing commensurate to the need.

I mean, if we’re going to talk about where the financial priorities of the United States government have been, it’s been in pouring money into the buildup for war making, for weapon making. It’s a pittance, according to Dr. Rafiq Tschannen of International Organization for Migration. 0.01 percent of the money spent on the military every day is spent for any kind of aid or assistance to refugees. And we were told that as many as 7,000 Iraqis would be admitted into the United States this year. Well, they’re certainly not going to meet that goal at the rate that they’re going now. We’ve seen dozens come in weekly, but, as you mentioned, 2,000 every day are fleeing from Iraq.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: David Smith-Ferri, talk to us about what you saw when you were there.

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: Well, we met a wide range of Iraqis, right, from all classes of society, many of them highly trained, highly educated, and, in almost every case, very reduced in their circumstances in Jordan as a result of having to flee and leave their livelihood, their homes, their communities. And certainly we met people who have suffered from, you know, from actual missile attacks and roadside bombs. And in every case, you’re meeting people whose situation is compounded by psychological trauma, by poverty, by displacement and the trauma of having to leave everything that, you know, your life is built upon.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you’ve produced a book of poetry, and the proceeds will go to assist refugees?

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: That’s right. We started a program, actually, called the Direct Aid Initiative, and it’s very much run by Iraqis on the ground who coordinate the services and identify the most needy medical cases. And all but $2, which covers just the printing of the book, are — from the sale of the book — are going to urgent medical needs of Iraqis in Damascus and in Syria.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the refugees, are there attempts to integrate them into the overall society, or are you seeing the rise of huge refugee camps, as well, throughout the countries there?

KATHY KELLY: Well, you wouldn’t speak of camps. There are neighborhoods that are maybe, I guess we’d say, low-income neighborhoods, and people have tried to fit themselves into healthcare and any kind of education that might be made available. But it’s very, very difficult. There is a lot of exclusion.

I mean, I see some people coping, and I’m in great admiration. I know one boy who had been kidnapped, and he was tortured while he was kidnapped. He was hung from a ceiling by an ankle chain, and his tormentors used electric prods. And so, he worked himself into the local soccer team, and he said, “I lost control over my life completely while I was kidnapped, but I’m in control out on the soccer field.” I know young girls who — they’re just ravenous to study English, and that’s what they’ve done for three years, while they’ve been excluded from the school system. You see people who are sending their children out to be laborers, and the children are proud, you know, because they’re the ones who are bringing some income into the family. So, people try to cope.

But there is a great deal of frustration and anger and bewilderment. I mean, I suppose it was a matter pride. One woman said to me, “Well, we didn’t really expect your country to do so much for us, because we saw what happened after Hurricane Katrina.” And is that how we want to be viewed? I mean, it doesn’t help our security to have other people looking at us as though, you know, we’re a stingy and a criminal country.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you started the Occupation Project both with the Congress, and now you’re talking about expanding it to the Presidential Occupation Project. Could you tell our audience what that’s about?

KATHY KELLY: Well, we think aspiring presidential candidates need to hear from people who have strong views about the war. I’m sure on October 27th it will be crucial to have swelling numbers of people in cities all across the country, as will happen. But then, you know, on the following days, I hope people will form affinity groups and decide how it is that they can really be involved in the primary process and go — for instance, we’re inviting people to come to Des Moines, Iowa, November 7th and 8th, and go to the offices, to the headquarters, to the campaign events of aspiring presidential candidates and say, “We’re going to occupy your office until you tell us what’s your plan to bring these troops home, bring them home alive and begin to pay reparations for the suffering we’ve caused in Iraq, but bring this war to an end.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what’s been the response in Congress to the Occupation Project?

KATHY KELLY: Well, I think, actually, a lot of the staffers in these offices agree with us. And if we begin to sing the names or read the names of people who have been killed, they feel deeply troubled. But they’re afraid, they’re frightened there. I think many feel that they don’t want to go up against the major weapon-making corporations, and they don’t want to be saddled with what might happen if there is rising violence in Iraq following withdrawal of troops. But pouring more weapons and more ammunition into this very volatile situation can’t possibly contribute toward security and peacemaking.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, David, can I ask you, in the last moments that we have, if you might be able to read a poem from your book, Battlefield Without Borders.

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: I’d be glad to. This is a poem about a young man named Moustafa that we know in Iraq, who was injured in the first days of the war. He lived in Baghdad, and he was — wanted to get information about the invasion as it approached Baghdad, and he went to his television. It didn’t work. He went up on the roof to get information — to fix the antenna. And the concussion of a missile threw him off the roof. He said, “It felt like the air kicked me.” This is called “If Irony Were Justice.”

Somewhere, Moustafa knows, he has a twin brother,

an American soldier with wheels for legs

a man who stands for nothing,

a man who is no longer a man

who urinates through a tube into a bag,

an American digging into the bureaucratic rubble of his government

trying to unearth something human,

trying to locate a surgeon’s fingers to reset the clock of his life

and point him forward.

If irony were iron,

Moustafa’s back would have held

when four years ago

the force of a US missile swept him like a branch from his roof

and dropped him two stories below in his garden.

If irony were bread,

a small round of dough, pounded, stretched, flattened

and thrown on a fire,

a bowl of hummus dribbled with olive oil,

a cool yogurt and cucumber salad,

Moustafa would never be hungry here in Amman.

For three years he rolled his chair through Baghdad —

one more broken body bent to its wheel —

and along concrete and barbed wire barriers that line the “Green Zone”

seeking reparation for his injuries.

I left no door unknocked, he says.

If irony were justice,

the U.S. military would have given him more than a letter:

Moustafa Samir Hassan was injured

when a missile exploded near his home

in the Karrada neighborhood of Baghdad on April 1st, 2003 …

It would instead have given him:

anesthesia, scalpels, transfusions, trained fingers, aftercare.

Somewhere, Moustafa knows, there is a clinic

with doctors who can repair his back,

who can reorient his life toward the future.

But for now, he is still trying to learn about this war from his television,

still climbing a ladder to fix an antenna on his house in Baghdad,

still falling

like a long-stemmed glass

to hard ground.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: How long —- we’ve got just a few seconds -—

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: Sure, sure.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: How long would the American people — if they’ve seen what you saw when you traveled there, what do you think would be their reaction, in terms of the war?

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: Well, I think people carry a lot of grief about this war locked up inside of them. And I think that the personal relationships that you can develop with individuals and with their stories would be a source of both strength and motivation for people to really be more active here. That’s what I think would happen.

Juan, perhaps people would like to know that I have a website for the book. It’s just —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yes.

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: It’s simply the title of the book, battlefieldwithoutborders.org, and people can learn about the book and about the assistance we’re providing and purchase it there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the proceeds go to help the Iraqi refugees.

DAVID SMITH-FERRI: Right, people like Moustafa, for example. Sure.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I want to thank both of you for being with us: Kathy Kelly, the executive director of Voices for Creative Nonviolence, and David Smith-Ferri, a poet and peace activist, his latest collection of poetry is titled Battlefield Without Borders.

Media Options