Guests

- Manning Marableprofessor and founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University. He is author of many books, including Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America’s Racial Future and helped edit The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero’s Life and Legacy Revealed Through His Writings, Letters, and Speeches.

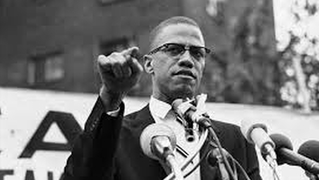

Today we spend the hour examining the life of Malcolm X — one of the most influential political figures of the 20th century. Saturday would have been his 82nd birthday. We broadcast excerpts of Malcolm X in his own words and speak to Columbia University professor Manning Marable, who is working on a major biography titled, “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention” to be published in 2009. Marable is the founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, we spend the hour examining the life and death of Malcolm X, one of the most influential political figures of the 20th century. Saturday would have been Malcolm X’s 82nd birthday. This is Malcolm X speaking a week before he was assassinated in 1965.

MALCOLM X: My house was bombed. It was bombed by the Black Muslim movement upon the orders of Elijah Muhammad. Now, they had come around to — they had planned to do it from the front and the back so that I couldn’t get out. They covered the front completely, the front door. Then they had come to the back, but instead of getting directly in back of the house and throwing it this way, they stood at a 45-degree angle and tossed it at the window so it glanced and went onto the ground. And the fire hit the window, and it woke up my second-oldest baby. And then it — but the fire burned on the outside of the house.

But had that fire — had that one gone through that window, it would have fallen on a six-year-old girl, a four-year-old girl and a two-year-old girl. And I’m going to tell you, if it had done it, I’d taken my rifle and gone after anybody in sight. I would not wait, ’cause in — and I said that because of this: The police know the criminal operation of the Black Muslim movement because they have thoroughly infiltrated it.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Malcolm X speaking at a rally of the newly formed Organization of Afro-American Unity, February 15, 1965. A week later he was shot dead at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem.

Today, we spend the hour with Professor Manning Marable and hear more clips of Malcolm X. Professor Marable, one of the leading experts on the life and legacy of Malcolm X, a professor at Columbia University, close to completing an important new biography called Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. It will be published in 2009. Welcome to Democracy Now!

MANNING MARABLE: Thank you, Amy. It’s great to be back.

AMY GOODMAN: It is great to have you with us. It was six days after he was speaking about the forces that were infiltrating that Malcolm X was gunned down.

MANNING MARABLE: That’s right, although there were pivotal decisions that were made after this address. Malcolm met with the key members of the two organizations that he had established: Muslim Mosque Incorporated, MMI, which was largely a group of former Nation of Islam members who left the NOI out of loyalty to Malcolm; and second, OAAU, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, which was a secular organization of African-American middle-class and working-class activists who joined Malcolm in building a more radical black nationalist movement in the mid-’60s.

The debate was, what do we do regarding the security of Malcolm X? The organization made two decisions that were highly contentious that evening: one, that none of Malcolm’s bodyguards, usually provided by Muslim Mosque Incorporated, would wear guns on the day of the big rally, which was scheduled on Sunday afternoon at the Audubon on the 21st of February; and secondly, no one would be searched, which actually was the standard protocol over the last several months at the Audubon, because Malcolm did not want to frighten off middle-class Negroes who were coming around and joining his movement.

But Malcolm’s own home had been firebombed the Sunday night before. I talked with James 67X Shabazz, who was Malcolm’s chief of staff, and others who eyewitnessed the assassination, and I challenged them personally and said, “How could you in good conscience have permitted Malcolm — even though he was the leader of the organization, nevertheless, there is a process of consultation. You were a his right-hand men and women. How could you have allowed him to do this?” And they said to me, “Brother Manning, you just didn’t know Brother Malcolm.” Then Malcolm insisted upon it.

So one of the riddles that I’m trying to solve in the autobiography is, why did Malcolm permit the context of the absence of security to occur on that particular day, especially at a time when the NYPD, the New York Police Department, and the FBI clearly set into motion decisions that facilitated the assassination on that day?

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain exactly what happened on February 21, 1965, from the time, actually six days before, that we just heard this clip.

MANNING MARABLE: Yes. To the best of our knowledge, the assassination conspiracy is directly at odds with what the New York District Attorney’s Office came up with in the murder trial of 1966. According to the New York prosecutors and the NYPD, there were three people who were responsible for the murder of Malcolm X: Talmadge Hayer, Thomas Johnson and Norman Butler. These three men were affiliated with the Nation of Islam. They were prosecuted and convicted of first-degree murder. At the time, New York state did not have a death penalty. They were sent to prison for a quarter of a century.

It is very clear to me that Butler and Johnson were not at the Audubon that day of the assassination. Talmadge Hayer was. He was shot by Reuben Francis, the chief bodyguard of Malcolm X. But the circumstances of the murder and all of the evidence that we have points to six men, not three, who were involved in the assassination; that the assassination was carefully planned for weeks; that, indeed, the day before the Audubon rally that Malcolm X and the OAAU held, that there was a one-hour walk-through that night of the killers.

And what’s curious were the actions of the NYPD and also the FBI. The NYPD ubiquitously followed Malcolm around wherever he spoke in the last year. They always had one to two dozen police officers. On this day, they pulled back the police guard. Many writers have already talked about this. But there were only two police officers in the Audubon at the time of the actual killing. And these two were assigned to the furthest end of the building, away from where the 400 people had gathered in the main ballroom. There were no cops outside. Usually, there were more than one or two dozen. So the police knew in advance something was going to occur that day.

AMY GOODMAN: The two men who you say weren’t there, where were they?

MANNING MARABLE: They were miles away doing other things, but they were not at the physical ballroom.

AMY GOODMAN: Have you spoken with them?

MANNING MARABLE: I’ve talked with one, Thomas Johnson. We did a three-and-a-half-hour interview. And what’s curious about it is that Johnson says to me, “You know, I hated Malcolm X. I still hate Malcolm X to this day,” and that “I tried to kill him. I was involved in a murder plot in Philadelphia several weeks before. Had I been ordered by Elijah Muhammad to kill Malcolm X that day, I would have gladly done it.” This was the content of his interview with me.

AMY GOODMAN: How would he try to kill him in Philadelphia?

MANNING MARABLE: They had conspired to carry out a shooting of Malcolm at the Philadelphia mosque. Malcolm was quite close to the people in Philadelphia, because of his close personal friendship and spiritual friendship with Wallace Muhammad, who was the head of the mosque, one of the younger sons of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who ultimately inherits the mantle of leadership. Today, he is Warith Muhammad, who is a leading figure in the American Muslim community.

Malcolm was targeted by elements within the NOI. But I think that what’s clear is there were three different groups that had an interest in silencing the new message of Malcolm X: law enforcement, and that includes the NYPD and the FBI; elements within the Nation of Islam, and by elements, I’m not entirely convinced that there was unanimity within the Nation of Islam — perhaps Elijah Muhammad took the view, not unlike Henry II, in Thomas a Becket, that “Will somebody rid me of this priest?” that I’m not sure if Elijah Muhammad gave the direct order — I haven’t come to that conclusion, but what is clear is that elements within the NOI, independently of Elijah Muhammad, clearly had set into motion the actions of murdering Malcolm; and then, finally, there were dissidents within Malcolm’s own entourage, especially within the MMI, who were extremely unhappy with the progressive movements of Malcolm in the last six to nine months of his life.

Those who had loyally left the Nation of Islam, who had given up everything that they knew and owned to join with this brother they deeply believed in personally, charismatically, then were shocked to discover Malcolm’s denouncing of racism in all its forms and, more importantly, Malcolm’s new emphasis, especially toward the end of 1964, on women leadership within the black freedom struggle. Lynn Shiflet, a key activist and leader of the OAAU, was directly at odds with James 67X, the head of MMI, these two groups Malcolm had created, one secular black nationalist progressive, one conservative and largely socialized by the tenets of the Nation of Islam.

So Malcolm, himself, felt torn. Malcolm, in his autobiography, describes himself trying to turn a corner, metaphorically, and that the people who had given up so much to elevate him, he did not want to leave behind, but at the same time history was pushing him toward a new kind of direction. We see this in only three weeks before the assassination, down in Alabama, where Malcolm goes to Selma, and he joins with Dr. King and John Lewis and SNCC in the struggle of the Selma march. And Malcolm reassures Coretta. He says, “I am not here to disrupt the effort to register African Americans to vote or to mobilize against structural racism in the heart of the Black Belt. I’m here because I want to lend my support to the struggle and the fight of Dr. King.” Malcolm was deeply committed to broadening the basis of the black freedom movement beyond the principles of integration and nonviolence of King, but not to destroy or disrupt the legitimacy of King’s role. Malcolm makes that very clear to Coretta. So Malcolm is moving in some new directions. This caused great consternation within the FBI, and it caused great consternation within Malcolm’s own entourage.

AMY GOODMAN: Where was Louis Farrakhan at this time?

MANNING MARABLE: Louis X was the head of the Boston mosque. One must remember he was Malcolm’s protégé. Indeed, Malcolm — the saying within the NOI by the late '50s was that they were Malcolm's ministers. There were about seven to 10 young men who idealized Malcolm. And while everyone was nominally loyal to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, nevertheless Malcolm’s ministers were charismatic, they were articulate, they were individuals, like himself, who joined the Nation of Islam because it was the only formation out there that spoke a black nationalist-oriented agenda and gave hope and pride and self-respect to African Americans. And they used the strategies of reaching out, of what they called, metaphorically, fishing. Farrakhan was the most brilliant and articulate of these ministers.

In 1963, when it became general knowledge that Elijah Muhammad had slept with a number of his secretaries and impregnated women within the Nation, this was anathema. Any other minister would have been tossed out, certainly silenced for at least 90 days. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad rolled on. And so, this hypocrisy bothered Malcolm. He consulted with the ministers. Farrakhan had a choice to make, and he decided to side with Elijah Muhammad. But it was a difficult choice for him.

I’ve interviewed Louis, as well, on several occasions. Farrakhan told me a striking story about when the two men last met in Malcolm’s automobile one night in early 1964, where Malcolm said to Farrakhan, “The things that are all happening to me right now, when they happen to you, the isolation, the opposition of all of the ministers, that will happen to you one day.” And Farrakhan looked at me and said, “And that was exactly what the brother had predicted.” Ten years later, that is what he faced, as well. Farrakhan is a riddle, and I haven’t made up my mind, but one of the great things, Amy, about writing history is that you don’t have to make up your mind right away. I’m doing more research on it now. In about two years from now, I’ll give you a more definitive conclusion.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Professor Manning Marable of Columbia University, writing the biography of Malcolm X. His new book, though, now is Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America’s Racial Future. We’ll be back with more excerpts of speeches of Malcolm X and more from Professor Marable. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now — continue to talk about Malcolm X. He would have been 82 years old this past Saturday. He was born on May 19, 1925. This is Malcolm X speaking out against the war in Vietnam. It’s August 10, 1963, at the Black Front Unity rally.

MALCOLM X: We believe that we who declared ourselves to be righteous Muslims should not participate in wars which take the lives of humans. As Muslims, we don’t go to war. We don’t get drafted. We don’t join anybody’s army. We don’t teach you not to go, because they’d put us in jail for sedition. I would never tell you not to go. I wouldn’t be that dumb. But I sure will tell you, if you’re dumb enough to go, that’s up to you. If you’re dumb enough to fight for someone who means you no good; if you’re dumb enough to fight for something that you have never gotten; if you are dumb enough to be as dumb as your other brothers who went into Korea and came back and still caught hell; if you’re dumb enough to follow in the footsteps of your older brothers during World War II, who fought all over the South Pacific, like Isaac Woodard, who came back here to this country and got his eyes punched out by police right here in this country; if you are dumb enough behind what you know about the white man today to let him stick his uniform on you and send you overseas to fight, well, you go the hell on and fight.

But I’m not that dumb. For me — and I can only speak for myself — I’ll go to jail. I’ll go to prison. Stick me in jail. Let me go to prison. But don’t give me your uniform, and don’t give me your rifle, because I might use it on someone that you don’t intend on me to use it. Don’t never put me in your airplane and fill it with bombs and tell me to go bomb the enemy. Why, I don’t have far to go to find that enemy. No.

We do not believe that this nation should force us to take part in such wars, for we have nothing to gain from it, unless America agrees to give us necessary territory, wherein we may then have something to fight for. Give us part of this country, and then if it’s attacked, we got something to fight for. But the days are gone when you think you can draft this little black man who’s sitting up here in the slums and ghetto of Harlem, who receives nothing but the worst schools and the worst education, who can’t even get a decent job, why, that cracker is out of his mind if he thinks our people are dumb enough to running after him today into some kind of war that he’s going to instigate and start for his own mercenary benefit. Those days are over.

AMY GOODMAN: Malcolm X, August 10, 1963. Professor Marable?

MANNING MARABLE: One of the themes in my biography-in-progress is trying to answer a critique that now predominates in Malcolm X literature, the argument that Malcolm X continued to change. And if you look at his life superficially, you see all of these changes, these lives of reinvention. He begins life as Malcolm Little. He becomes Detroit Red, a notorious gangster in Boston’s Roxbury and in Harlem, New York. He becomes Malcolm X when he joins the Nation of Islam. Malik El-Hajj El-Shabazz —

AMY GOODMAN: Served time in prison during his gangster days.

MANNING MARABLE: That’s right, serves seven — that’s right. He leaves. He joins the Nation of Islam. And then he becomes El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

And the tendency from those especially close to those of orthodox Sunni Islam and the integrationist perspective of Alex Haley, who was the co-author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, is to frame Malcolm as a kind of evolving integrationist. Well, clearly, that’s just false. Malcolm was a committed internationalist at the end of his life, but he was also a black nationalist, in the sense that he fought for and died for the concept of self-determination for the people of African-American descent in this continent and fought for the right of that population to determine for itself what it wished to become. But what I find in my own research is greater continuity than discontinuity.

What I see in Malcolm is that his father Earl Little and Louise Little were committed Garveyites, advocates of black nationalism and Pan-Africanism in Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, joined in the 19-teens and '20s; that Earl Little was the leader of the UNIA chapter branch in Omaha, Nebraska, then in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in East Chicago, Indiana, and then finally in Lansing — in Detroit, Michigan; that there was a long legacy and a foundation of Malcolm's evolving politics that —

AMY GOODMAN: And his father’s death?

MANNING MARABLE: And his father’s very tragic death in 1931 and his mother’s institutionalization in a mental hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in January 1939. All of these events tragically framed Malcolm and made his youth terribly tragic. But if we focus on the gifts that his parents gave him, it gave him a kind of political and cultural foundation, and especially the closeness and the kinship that he felt toward Wilfred, Philbert, Hilda and the other siblings in the Little family, the other seven children. And Malcolm is often seen as a kind of a lone ranger, that he did not have the kind of family or sibling contact that provided support for him, that he was kind of a lost child. That simply is not true. And so, we need to see greater continuity.

If you listen to the '63 speech clip we just heard, he's still a member of the Nation of Islam, but he’s hitting themes that 80 percent of which are directly in concert with what he’s talking about a year and a half later after he’s left the Nation. And so, I don’t think that it’s fair to Malcolm to say that Malcolm was simply an inconsistent weather vane, but rather, we need to look at the organic evolution of his mind and how he struggled to find different ways to empower people of African descent by any means necessary.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, it’s interesting. August 10, 1963, that’s right before the March on Washington, and here is Malcolm speaking out vehemently against the Vietnam War.

MANNING MARABLE: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. King, the famous speech he gave against the war was April 4, 1967.

MANNING MARABLE: That’s right. But that just shows you that Malcolm was cutting-edge, that Malcolm was the first prominent African American, arguably the first prominent American leader, to come out against the Vietnam War. And this was even during the time that he was in the Nation of Islam. It was Malcolm X who said that we had to go beyond civil rights to human rights. It was Malcolm X who said we don’t appeal to the U.S. Congress to interrogate structural racism inside the United States; we take that to the United Nations. Three years later, it was Dr. King that followed out a path that Malcolm had clearly chartered for him, so that the internationalization and the Pan-Africanism of Malcolm that he advocated in 1964, all of that forms the foundation of what becomes Black Power and Pan-Africanism of Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panther Party three, four years later. Malcolm was the forerunner to the explosion of the black liberation struggle throughout the globe and black consciousness in South Africa and in the Caribbean. And so — but that organically grew out of, not a rupture from his past, but a growth from the foundations that his parents and others had established before, many years before.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me go to another clip of Malcolm X.

MALCOLM X: Who are you? You don’t know. Don’t tell me “Negro.” That’s nothing. What were you before the white man named you a Negro? And where were you? And what did you have? What was yours? What language did you speak then? What was your name? It couldn’t have been Smith or Jones or Burch or Powell. That wasn’t your name. They don’t have those kind of names where you and I came from. No, what was your name? And why don’t you now know what your name was then? Where did it go? Where did you lose it? Who took it? And how did he take it? What tongue did you speak? How did the man take your tongue? Where is your history? How did the man wipe out your history?

AMY GOODMAN: That was Malcolm X.

MANNING MARABLE: That clip was about five years before his death. And Malcolm, at a time when in the Nation of Islam Malcolm ironically was one of the most prominent speakers of African-American descent in the United States, within his own organization he was — he found himself under fire. During 1962 and early '63, Malcolm — the Nation of Islam's major newspaper that Malcolm had co-founded, Muhammad Speaks, refused to run a single story about him. And so, the goal Malcolm had in collaborating with journalist Alex Haley in the writing of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, the original goal he had was to appeal to Elijah Muhammad, to win his good graces back, that Malcolm was under fire by those — a coterie of lieutenants around Elijah, and he wanted to show the world the emancipatory power of the vision and creed of the Nation of Islam. That was the purpose of writing the book, the original purpose.

Haley had an entirely different agenda. He was a Republican. He despised Malcolm X’s black nationalist creed. But he was a journalist, and he understood the power of charisma.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the missing three chapters? We’ve talked about it on this broadcast before. But talk more about Alex Haley, and talk about the FBI.

MANNING MARABLE: In late 1961, Alex Haley and white journalist Alfred Balk were approached by the Chicago office of the FBI to funnel misinformation that was critical of the Nation of Islam into a magazine article that would be read nationwide. They did so. It was called “The Black Merchants of Hate,” published in The Saturday Evening Post in late February 1962. In effect, Haley played the role of a misinformation agent of the FBI. Ironically, since the article said the Nation of Islam hates white people, they think they’re devils, and they don’t want anything to do with integration, Elijah Muhammad loved the article. He thought it was great. And so, that helped to create that bridge that led several months later to Malcolm and Haley negotiating an agreement where they would write an autobiography together.

The problem with the autobiography: It’s a magnificent work of literature, but it is highly misleading. It’s really three books, not one. The bulk of the book, from chapters one to about 14, serves the original purposes of Malcolm. It’s a book that emphasizes, not unlike Saint Augustine, the early Christian leader who wanted to show the degradations of his own personal life and the emancipatory power of Christ — this is not unlike what Malcolm was writing, and he was familiar with that text. Malcolm wanted to tell a tale of transformation and hope within the NOI ideology and creed. But after he broke with the Nation of Islam, the second part of the book, the last five chapters, then swings in a very different direction. He wants to tell the story of going to Mecca, of the power of epiphany, and then being liberated from a creed of racism.

But how much is that a spiritual journey and how much of that is political necessity? My analysis of Malcolm in '64 says that it's really both. Malcolm wants to be directly involved in the leadership of the black freedom struggle, the civil rights movement. He wants to redefine that movement. But to do that, he must be engaged with the actual leadership. He actually goes, when he returns to the U.S. from Saudi Arabia and Ghana, and apologizes to James Farmer, the head of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, a man he had bitterly debated, and two other civil rights leaders, because he wants to be involved in that movement. He goes down to Selma, Alabama, in early ’65. He brings Fanny Lou Hamer and representatives of SNCC to the stage at the Audubon in late 1964. So he is actively trying to build a broad-based black united front.

In the missing chapters of the autobiography, he spells out what that front is going to look like.

AMY GOODMAN: So, they were written.

MANNING MARABLE: Oh, yes. And in those chapters, which are largely written, my estimation, is roughly between September '63 to January ’64, Malcolm spells out a program. You know, for years, I've always read the autobiography and sensed something’s missing here. Malcolm was a consummate political actor, and in his defining document of his life, there’s no political program, there is no economic or educational or social program? Where is it? And the answer is, is that it gets largely taken out.

Now, according to Haley, after Malcolm’s assassination, it gets taken out because Malcolm agreed to it after his return from Mecca. That may be true. But what we do know that is true is that when Malcolm is assassinated on February 21, 1965, within two-and-a-half weeks the original publisher, Doubleday, exes the deal on the book. And in early March '65, they cancel the contract. That's why the book is published at the end of the year by Grove, not Doubleday. It was the most disastrous decision in corporate publishing history. They lost millions of dollars on this. Serves them right.

AMY GOODMAN: When we come back, you saw these chapters, or you saw an excerpt —

MANNING MARABLE: Very briefly.

AMY GOODMAN: — very briefly. They’re being held in a safe. And we’re going to talk about that in a minute and also talk about what happens to leaders like Malcolm X, to their writings, what happens to their possessions. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. We’re speaking with Professor Manning Marable, biographer of Malcolm X. He’s a professor at Columbia University. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Our guest is Columbia University professor Manning Marable, biographer of Malcolm X — the biography will come out in two years — his most recent book, Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America’s Racial Future. Very quickly, what you got to see of these three chapters of The Autobiography of Malcolm X that most people have never seen.

MANNING MARABLE: The chapters were excised from the original manuscript, not published in 1965. Those fragments were sold off in an auction in January 1993 to an attorney in Detroit, Gregory Reed, who purchased them. Several years ago, as I was writing Living Black History — and I describe the episode in the book — I flew to Detroit to meet with Mr. Reed to see these chapters. He gave me a generous 15 minutes to look at the text. That’s not long, but that’s enough for me, since I’ve read so many speeches by Malcolm and writings that I could within a few minutes pretty much identify when he wrote those texts. They were written in late ’63, early ’64.

Malcolm was trying to find a way to create what we would have, in the '90s, called the Million Man March, a broad-based, eclectic ideologically black united front, from the Republicans to communists within the African-American community, around building strong black institutions and black leadership. And I think that it's really imperative for black America to study and understand those missing elements of Malcolm to understand the full man. We still have an active suppression of the full range of his speeches and writings. And that, more than anything else, needs to be brought out to the public.

Living Black History and the book that I did just prior to that, The Autobiography of Medgar Evers, speaks about another issue: the deliberate suppression by white institutions of any evidence of either genocide against African Americans or the physical elimination of black leadership. In the cases of both Malcolm X and Medgar Evers, there has been a real suppression of the quality of their thought and also their dynamic leadership in two different phases of the black freedom struggle in the 1960s.

AMY GOODMAN: Medgar Evers, the leader who was born just a few months after Malcolm X, contemporaries, also assassinated in his front yard.

MANNING MARABLE: That’s right. They were born only a few months apart. Myrlie Evers-Williams, just a legend in the civil rights community, and I collaborated a year and a half ago to write The Autobiography of Medgar Evers. It’s the first book that — it’s now available — combines the speeches and writings and key documents that explain the history of this man. I’m trying to, by preserving the life and thought of those in the black freedom struggle, like Brother El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz and Medgar Evers, to make all Americans aware that if you do not preserve the history of struggling for democracy, you can lose, not just that heritage, but can you lose democracy itself. That is, we destroyed Medgar Evers’s material from the NAACP after his assassination. Three-fourths of it was thrown into the garbage, literally, and destroyed. And many of the materials I used in that book were only saved from the garbage bin just by accident.

AMY GOODMAN: Before I ask you about presidential politics today — then we’re going to play a major clip of Malcolm X — very quickly, Yolanda King just died, 51 years old, eldest daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King. You taught her at Smith?

MANNING MARABLE: She was not in my classroom formally, but I knew her well. My first job getting out of grad school was for two years as a lecturer at Smith College, and that’s where I met Yoki. She was a wonderful person, a great individual. Over the more recent years, I had really lost touch with her. But my heart goes out to her family. It’s a real tragedy.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Marable, today, politics today. And we only have a minute to talk about it, but just your thoughts, informed by the work that you have done for so many years?

MANNING MARABLE: There’s a link between history and politics. And the link is, is that — the irony is that in our historical work we can frame a black intellectual agenda. Where is the black political agenda for 2008? It’s radically disappearing. The Congressional Black Caucus from 15 years ago was an assertive independent voice for change in the first Bush administration around the anti-apartheid struggle two decades ago. Where is that voice today? The NAACP, the Urban League, civil rights organizations are now corporatized. They either reach into the ranks of corporate America to find its leadership, or they’re funded by corporations. And so, I think that there needs to be a critical examination of whither the black left, and more generally, the American left, because without an effective, articulate Democratic left voice in this country, the liberals will never be accountable to even their own politics. And that’s what’s missing in ’08.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Professor Marable, we’re going to turn now to a voice of the past. “By Any Means Necessary” was the name of Malcolm X’s speech. This is Malcolm X speaking June 28, 1964.

MALCOLM X: As many of you know, last March, when it was announced that I was no longer in the Black Muslim movement, it was pointed out that it was my intention to work among the 22 million non-Muslim Afro-Americans and to try and form some type of organization or create a situation where the young people, our young people, the students and others, could study the problems of our people for a period of time and then come up with a new analysis and give us some new ideas and some new suggestions as to how to approach a problem that too many other people have been playing around with for too long, and that we would have some kind of meeting and determine at a later date whether to form a black nationalist party or a black nationalist army.

There have been many of our people across the country from all walks of life who have taken it upon themselves to try and pool their ideas and to come up with some kind of solution to the problem that confronts all of our people. And tonight, we are here to try and get an understanding of what it is they’ve come up with.

Also, recently, when I was blessed to make a trip or a pilgrimage, a religious pilgrimage, to the holy city of Mecca, where I met many people from all over the world, plus spent many weeks in Africa trying to broaden my own scope and get more of an open mind to look at the problem as it actually is, one of the things that I realized, and I realized this even before going over there, was that our African brothers have gained their independence faster than you and I here in America have. They’ve also gained recognition and respect as human beings much faster than you and I.

Just 10 years ago on the African continent, our people were colonized. They were suffering all forms of colonization, oppression, exploitation, degradation, humiliation, discrimination, and every other kind of -ation. And in a short time, they have gained more independence, more recognition, more respect as human beings than you and I have. And you and I live in a country which is supposed to be the citadel of education, freedom, justice, democracy, and all of those other pretty-sounding words.

So it was our intention to try and find out what was our African brothers doing to get results, so that you and I could study what they had done and perhaps gain from that study or benefit from their experiences. And my traveling over there was designed to help to find out how.

One of the first things that the independent African nations did was to form an organization called the Organization of African Unity. […] The purpose of our […] Organization of Afro-American Unity, which has the same aim and objective to fight whoever gets in our way, to bring about the complete independence of people of African descent here in the Western hemisphere, and first here in the United States, and bring about the freedom of these people by any means necessary. That’s our motto. […]

The purpose of our organization is to start right here in Harlem, which has the largest concentration of people of African descent that exists anywhere on this Earth. There are more Africans here in Harlem than exist in any city on the African continent, because that’s what you and I are: Africans. […]

The Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights are the principles in which we believe, and that these documents, if put into practice, represent the essence of mankind’s hopes and good intentions; desirous that all Afro-American people and organizations should henceforth unite so that the welfare and well-being of our people will be assured; we are resolved to reinforce the common bond of purpose between our people by submerging all of our differences and establishing a nonsectarian, constructive program for human rights; we hereby present this charter:

I. The Establishment.

The Organization of Afro-American Unity shall include all people of African descent in the Western hemisphere […] In essence what it is saying, instead of you and me running around here seeking allies in our struggle for freedom in the Irish neighborhood or the Jewish neighborhood or the Italian neighborhood, we need to seek some allies among people who look something like we do. And once we get their allies. It’s time now for you and me to stop running away from the wolf right into the arms of the fox, looking for some kind of help. That’s a drag.

II. Self-Defense.

Since self-preservation is the first law of nature, we assert the Afro-American’s right to self-defense.

The Constitution of the United States of America clearly affirms the right of every American citizen to bear arms. And as Americans, we will not give up a single right guaranteed under the Constitution. The history of unpunished violence against our people clearly indicates that we must be prepared to defend ourselves or we will continue to be a defenseless people at the mercy of a ruthless and violent racist mob.

AMY GOODMAN: Malcolm X, June 28, 1964, at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, where he was gunned down about half a year later. If he were alive today, he would be 82 years old.

Media Options