Topics

Guests

- Jon Michael Turnerformer Marine with the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines.

- Jason Hurdin 2004 he was deployed to central Baghdad with Tennessee’s 278th Regimental Combat Team.

US veterans gathered in Maryland this past weekend to testify at Winter Soldier, an eyewitness indictment of atrocities committed by US troops during the ongoing occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soldiers spoke of free-fire zones, the shootings and beatings of innocent civilians, racism at the highest levels of the military, sexual harassment and assault within the military, and the torturing of prisoners. While the corporate media ignored the story, we broadcast their voices. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

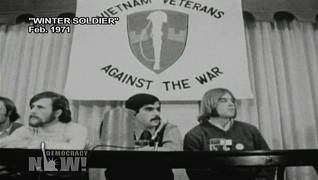

AMY GOODMAN: Iraq and Afghanistan veterans gathered in Maryland this past weekend to testify at Winter Soldier, an eyewitness indictment of atrocities committed by US troops during the ongoing occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Organized by Iraq Veterans Against the War, the event was modeled after the historic 1971 Winter Soldier hearings held during the Vietnam War.

Over the weekend, war veterans spoke of free-fire zones, the shootings and beatings of innocent civilians, racism at the highest levels of the military, sexual harassment and assault within the military, and the torturing of prisoners.

Although Winter Soldier was held just outside the nation’s capital, it was almost entirely ignored by the American corporate media. A search on the Lexis database found that no major television network or cable news network even mentioned Winter Soldier over the weekend, neither did the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times or most other major newspapers in the country. The editors of the Washington Post chose to cover Winter Soldier but placed the article in the local section.

On Friday, Democracy Now! broadcast from Winter Soldier. This week, we play excerpts from the proceedings. We begin with Jon Michael Turner, who fought with the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines.

JON MICHAEL TURNER: Good afternoon. My name is Jon Michael Turner. I currently reside in Burlington, Vermont. I served with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines as an automatic machine gunner. There’s a term, “Once a Marine, always a Marine.” But there’s also the term, “Eat the apple, F the corps, I don’t work for you no more.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was Jon Michael Turner, stripping his medals and ribbons from his chest and throwing them into the audience to the applause of attendees at Winter Soldier. Turner then went on to describe some of his time in Iraq.

JON MICHAEL TURNER: On April 18, 2006, I had my first confirmed killed. This man was innocent. I don’t know his name. I called him “the fat man.” He was walking back to his house, and I shot him in front of his friend and his father. The first round didn’t kill him, after I had hit him up here in his neck area. And afterwards he started screaming and looked right into my eyes. So I looked at my friend, who I was on post with, and I said, “Well, I can’t let that happen.” So I took another shot and took him out. He was then carried away by the rest of his family. It took seven people to carry his body away.

We were all congratulated after we had our first kills, and that happened to have been mine. My company commander personally congratulated me, as he did everyone else in our company. This is the same individual who had stated that whoever gets their first kill by stabbing them to death will get a four-day pass when we return from Iraq.

There was one incident, where we got into a firefight just south of the government center about 2,000 meters. We had no idea where the fire was coming from. And the way our rules of engagement were, pinpoint where the fire is coming from and throw a rocket at it. So, at that being said, we still didn’t know where the fire was coming from, and an eighty-four-millimeter rocket was shot into a house. I do not know if there was anyone in it. We do not know if that’s where the fire was coming from. But that’s what was done.

Please go to the next image. This man right here was my third confirmed killed. As you can see, he was riding his bicycle. Later on in the day, we went ahead, and we had CBS’s Lara Logan with us, but she was with the other squad, and so she wasn’t with us. So, myself and two other people went ahead and took out some individuals, because we were excited about the firefight we had just gotten into, and we didn’t have a cameraman or woman with us. With that being said, any time we did have embedded reporters with us, our actions would change drastically. We never acted the same. We were always on key with everything, did everything by the books. The man on the bicycle, he was left in the street for about ten minutes until we realized that we needed to leave where we were. And his body was dragged about ten feet to the right of him, where his body was thrown behind a rock wall and his bicycle was thrown on top of him.

Another thing that we used to do a lot was recon by fire, where we would go ahead and try to start a firefight if we felt threatened in any way, shape or form. There was one particular incident where we were working with the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi Special Forces in downtown Ramadi, and with our squad and the Iraqi Army there was also lieutenant colonels, majors, first sergeants and sergeant majors — sorry, sergeants major. With that being said, the Iraqi Army would go into the house, kick in the doors and then go ahead and shoot. And there were loud bursts of machinegun fire. We thought we were taking fire, but then we later found out that it was them.

House raids — because we were a grunt battalion, we were responsible for going on several patrols. A lot of the raids and patrols we did were at night around 3:00 in the morning, around there. And what we would do is just kick in the doors and terrorize the families. That was an image taken around 3:00 in the morning through night vision goggles. And that is the segregation of the women and children and the men. If the men of the household were giving us problems, we’d go ahead and take care of them anyway we felt necessary, whether it be choking them or slamming their head against the walls. If you go back to that one picture, that was one man that wasn’t taking — that was taken care of in a very bad way, because of all the wiring that he had. We considered it IED-making material.

On my wrist, there’s Arabic for “F you.” I got that put on my wrist just two weeks before we went to Iraq, because that was my choking hand, and any time I felt the need to take out aggression, I would go ahead and use it.

Please go to the next picture. Next, there’s an instance of detainees and how they were treated in a nice manner.

Next, that is the Fatima Mosque minaret. As you can see, it is ridden with bullet holes and holes in the top of it. Those were from mortars. And the next video that I’m going to show you is a tank round that went into that minaret, where we weren’t sure if we were taking fire or not. Actually, I’ll talk about this one. This is after one of the guys in a weapons company had gotten shot. This is a way that we would take out our aggression. For those of you who don’t know, it is illegal to shoot into a mosque, unless you were taking fire from it. There was no fire that was taken from that mosque. It was shot into because we were angry.

Can you please play the next video?

- [clip] We are on [inaudible], trying to suppress the blue-and-white minaret named Madinat al-Zahra. Hellraiser, Hellraiser, go ahead. You can move the tank around that door over — at that mosque door. Another round Kilo Two.

Next image. That — OK, with that being said, there’s many more stories and incidents for me to talk about, although we don’t have the time to. But this just goes to show you that that was the aftereffect of the tank round. This just goes to show you that everyone sitting up here has these stories, and there’s been over a million trips that have gone in and out of Iraq, so the possibilities are endless.

Next image, please. The reason I am doing this today is not only for myself and for the rest of society to hear, but it’s for all those who can’t be here to talk about the things that we went through, talk about the things that we did.

Next image. Those four crosses and this memorial service were for the five guys in Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines that we lost. Throughout our unit, we had eighteen that got killed. With that being said, that is my testimony. I just want to say that I am sorry for the hate and destruction that I have inflicted on innocent people, and I’m sorry for the hate and destruction that others have inflicted on innocent people. At one point, it was OK. But reality has shown that it’s not and that this is happening and that until people hear about what is going on with this war, it will continue to happen and people will continue to die. I am sorry for the things that I did. I am no longer the monster that I once was. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Marine, Jon Michael Turner, fought with the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines. The videos and photos the soldier showed can be seen at our website, democracynow.org. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return now to our coverage of Winter Soldier, Iraq and Afghanistan.

JASON HURD: My name is Jason Hurd. I recently completed ten years of honorable service to my country in both the US Army and the Tennessee National Guard. I served in central Baghdad from November of ’04 to November of ’05. I’m from a little place nestled in the mountains of East Tennessee called Kingsport, and hence the mountain man beard. People don’t really trust you if you’re clean-shaven there. Kingsport is truly small-town America. There is a Baptist church on every street corner, and even the high-class restaurants serve biscuits and gravy.

My father, Carl C. Hurd, who died in 2000 — he was seventy-six years old — he was a Marine during World War II. Obviously, I was a latecomer in his life; he didn’t have me until his late fifties. As a matter of fact, when he died, shortly after that, I have the two World War II battles he participated in tattooed on my arm, and my father had the same tattoo. He was in the Pacific campaign and participated in the battles of Tarawa and Guadalcanal, which were some of the bloodiest occurrences of that war.

I decided to join the military in 1997. I was seventeen years old. I had just graduated from high school, and I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do with my life. My father was adamantly opposed to me serving in the military. My father was one of the most warmongering, gun-loving people you could ever meet, but he didn’t feel that way when it came to his son, because he knew the negative psychological consequences of combat service. Looking back — looking back, I know for a fact that my father had post-traumatic stress disorder. He had the rage, he had the nightmares, and he had the flashbacks.

AMY GOODMAN: Jason Hurd went on to describe his time in Iraq. In 2004, he was deployed to central Baghdad with Tennessee’s 278th Regimental Combat Team.

JASON HURD: One of the observation points that overlooked the Tigris River looked out at the old Republican Guard barracks, which were across the river. And there was one of those buildings that was sort of dilapidated; however, we knew that squatters had taken this building over, and we actually used to make jokes that this place looked like a crack house and that they were running drugs out of there. We had no evidence of that; it was just joking.

One day, Iraqi police got into an exchange of gunfire with some unknown individuals around that building. Some of the stray rounds came across the Tigris River and hit the shield of one of our Hummers. The gunner atop that Hummer decided to open fire with his fifty-caliber machinegun into that building. He expended about a case and a half of ammunition. And I’m no weapons expert — I’m a medic — but I talked to some of my colleagues just the other night, and to put this into perspective for you all, each case of fifty-cal ammunition holds about 150 rounds. A case and a half is well over 200 rounds. Over 200 rounds of fifty-caliber ammunition could take out just about every single person in this room. We fired indiscriminately and unnecessarily at this building. We never got a body count, we never got a casualty count afterwards. Another unit came through and swept up that mess.

Ladies and gentleman, things like that happen every day in Iraq. We react out of fear, fear for our lives, and we cause complete and utter destruction.

After we finished the mission manning those observation points, we moved on. My platoon specifically was tasked with running security escort for two explosive ordnance teams, one US Navy and one Australian EOD team. On day one, the US Navy team took us all aside for some specialized training. They took us aside and said, “Look, EOD teams are some of the most highly targeted entities in Iraq. The reason being is because, hey, we’re the guys that go out and we disarm car bombs, we mess up the tactics and the operations of the insurgency. That’s why we’re highly targeted. So you guys have to use more aggressive tactics to protect us.”

And they explained to us that what we were to do is keep a fifty-meter perimeter, a fifty-meter bubble around our trucks at all times, whether we were driving down the road or whether we’re stationary. And if anything comes in that fifty-meter bubble, we’re to get it out immediately. If it doesn’t want to move, we use what are called levels of aggression. Your first option is to try to push it out by using hand signals, hand and arm signals. Your next option is to fire a warning shot into the ground. And from there on, you walk bullets up the car. And your last option is to shoot the person driving the car. This is for our own protection. Car bombs are a real danger in Iraq. In fact, that’s the vast majority of what I saw in Baghdad, is car bombings. My unit adhered strictly to these guidelines for a few weeks.

But as time went on and the absurdity of war set in, they started taking things too far. Individuals from my unit indiscriminately and unnecessarily opened fire on innocent civilians as they’re driving down the road on their own streets. My unit — individuals from my platoon would fire into the grills of these cars and then come back in the evenings after missions were done and brag about it. They would say, “Hey, did you guys see that car I shot at? It spewed radiator fluid all over the ground. Wasn’t that cool?” I remember thinking back on that and how appalled I was that we were bragging about these things, that we were laughing, but that’s what you do in a combat zone. That is your reality. That is how you deal with that predicament.

After we finished the EOD escort missions, we moved on to another mission: patrolling the Kindi Street area, which is right outside of the Green Zone. Kindi Street is a relatively upscale neighborhood. Some of the houses in the Kindi area would cost well over $1 million here in America. This area, from what we were told, had no violent activity at all, up until the point we started patrolling this area. We were the first US military to do so on any regular basis. So we went in. We started doing patrols through the streets. We started getting out and meeting and greeting the local population, trying to figure out what sort of issues they had, how we could resolve those issues.

I remember we were out on a patrol one day, a dismounted patrol, and we were walking by a woman’s house. She was outside in her garden doing some work. We had our interpreter with us, and our interpreter threw up his hand and said “Salaam aleikum,” which is their greeting in Iraq. It means “Peace of God be with you.” And he translated back to us what she said. She said, “No. No peace of God be with you.” She was angry, and she was frustrated. And so, we stopped, and our interpreter said, “Well, what’s the matter? Why are you so angry? We’re here protecting you. We’re here to ensure your safety.”

And that woman began to tell us a story. Just a few months prior to this, her husband had been shot and killed by a United States convoy, because he got too close to their convoy. He was not an insurgent; he was not a terrorist. He was merely a working man trying to make a living for his family. To make matters worse, a few weeks later, there was a Special Forces team who operated in the Kindi area. And as you know, Special Forces do clandestine operations. And so, even though this was my unit’s area of operation, we didn’t know what the Special Forces teams were actually doing there. They holed up in a building there in the Kindi Street area and made a compound out of it. A few weeks after this man died, the Special Forces team got some intelligence that this woman was supporting the insurgency. And so, they conducted a raid on her home, zip-tied her and her two children, threw them on the floor. And I guess her son was old enough to be perceived as a possible threat, so they detained him and took him away. For the next two weeks, this woman had no idea whether her son was alive, dead or worse. At the end of that two weeks, the Special Forces team rolled up, dropped her son off and, without so much as an apology, drove off. It turns out they had found they had acted on bad intelligence. Ladies and gentleman, things like that happen every day in Iraq. We’re harassing these people, we’re disrupting their lives.

I want to tell you a very personal story, and I want you all to bear with me, because this is always difficult for me to tell. One day, we were on another dismounted patrol through the Kindi Street area. We were walking past an area we called “the garden center,” because it was literally a fenced-off garden. As is policy, we are to keep all cars and individuals away from our formation. And so, a car was approaching us from the front. I was at the rear of the formation, because I was the medic and the medics hang out at the back with the platoon sergeant in case anything happens up front so you can respond. They waved the car off down a side street, so that it would not come near our formation.

As I made it up to that side street, the car had turned around and was coming back towards us, because the street was blocked off by a concrete T barrier at the other end. So I began doing my levels of aggression. I held up my hand, trying to get the car to stop. The car sped up. And I thought to myself, oh, my god, this is it. This is someone who is trying to hurt us. And so, instead of doing what I should have done according to policy and raising my weapon, instead, I did what you should never do, and I took my hands off of my weapon altogether and began jumping up and down, waving my hands back and forth, trying to get this car to stop and see me. The car kept coming. And so, I raised my weapon, and the car kept coming. I pulled my selector switch off of safe, and the car kept coming.

I was applying pressure to my trigger, getting ready to fire on the vehicle, and out of nowhere, a man came off of the side of the road, flagged the car down and got it to pull over. He walked around to the driver’s side door, opened it up, and out popped an eighty-year-old woman. Come to find out, this woman was a highly respected figure in the community, and I don’t have a clue what would have happened had I opened fire on this woman. I would imagine a riot.

Ladies and gentlemen, I hate guns. I spent ten years in the military, and I carried two of them on my side in Iraq, but I think they should be melted down and turned into jewelry. To this day, that is the worst thing that I have ever done in my life. I am a peaceful person, but yet in Iraq I drew down on an eighty-year-old geriatric woman who could not see me, because I was in front of a desert-colored vehicle —- or, excuse me, desert-colored building wearing desert-colored camouflage.

Another personal story from my experience, the next mission that we got was to man the main checkpoint that entered into the Green Zone. We called this checkpoint Slaughterhouse 11, because the very first day we got into country, a car bomb went off in that checkpoint. We were a couple of blocks away at the time, and none of us knew what it was, so we were asking around, “What was that? What was that?” Oh, that’s the car bomb that goes off every single morning at checkpoint 11. And that’s where the name Slaughterhouse 11 comes from. You could literally set your watch by the time a car bomb would explode in that checkpoint every day.

Towards the end of my tour, we got the mission to take that checkpoint over. And my unit said, “What is the matter with you people? We’re getting ready to go home in just a couple of months. Why are you giving us Slaughterhouse 11? Are you wanting us to die?”

Day one that we took that checkpoint over and ran it ourselves, a car bomb drove into it and exploded. We found out that there was over a thousand pounds of explosives in that car afterwards. Luckily, it did not hurt any of my guys. My guys were able to find cover, and it didn’t hurt them. But it killed untold numbers of Iraqi civilians in queue to come into the checkpoint and injured so many more. I treated five people that day myself, and I would imagine twenty or thirty others got carted off into civilian ambulances before I could get to them.

But I have an image that is burned into my mind to this very day. And I remember a man running towards me at the front of the checkpoint, carrying a young seventeen— or eighteen-year-old Iraqi guy, very thin, very sort of pale. He came running to me with this guy and laid him at my feet. I looked down at him, and the guy was missing from here to here of his arm, and his forearm was only held on by a small flap of skin. The bones were protruding, and it was bleeding profusely. He had shrapnel wounds all over his torso. And when I log-rolled him onto his side to check his rear for wounds, I noticed that his entire left butt cheek was missing, and it was bleeding profusely, and it was pooling blood. And to this day, I have that image burned in my mind’s eye. Almost every couple of days, I will get a flash of red color in my mind’s eye, and it won’t have any shape, no form, just a flash of red. And every time, I associate it with that instance. So not only are we disrupting the lives of Iraqi civilians, we’re disrupting the lives of our veterans with this occupation.

You know, conservative statistics say that the majority of Iraqis support attacks against coalition forces, the majority of Iraqis support us leaving immediately, and the majority of Iraqis see us as the main contributors to the violence in Iraq. This gives us a view at the prevailing sentiment in Iraq. And I’d like to explain it to everyone this way, especially in the South, because it rings with some semblance of truth to people down there. If a foreign occupying force came here to the United States, and regardless of what they told us, whether they told us they were here to free us, to liberate us and to give us democracy, do you not think that every person that owns a shotgun would not come out of the hills and fight for their right to self-determination?

And I’d like to sum it up like this: the prevailing sentiment in Iraq is this — another time that I was out on patrol in the Kindi Street area — as I said, part of our mission was to meet and greet the local population and find out what their problems were — and so, I approached a man with my interpreter on the side of the road, and I asked him, I said, “Look, are your lives better because we’re here? Are you safer? Do you feel more secure? Do you feel like we are liberating you?” And that man looked at me straight in the eye, and he said, “Mister, we Iraqis know that you have good intentions here. But the fact of the matter is, before America invaded, we didn’t have to worry about car bombs in our neighborhoods, we didn’t have to worry about the safety of our own children as they walked to school, and we didn’t have to worry about US soldiers shooting at us as we drive up and down our own streets.”

Ladies and gentlemen, the suffering in Iraq is tearing that country apart. And ending that suffering begins with a complete and immediate withdrawal of all of our troops. Thank you very much.

AMY GOODMAN: Jason Hurd was with Tennessee’s 278th Regimental Combat Team in Iraq. He testified at the Winter Soldier hearings this weekend at the National Labor College in Silver Spring, Maryland, joining hundreds of other active-duty and veterans from both Afghanistan and Iraq. The Winter Soldier hearings were modeled on what happened thirty-seven years ago in Detroit, Michigan, the Winter Soldier Investigation, where soldiers from Vietnam came back and described atrocities they themselves had been involved with. We will continue to run these testimony throughout the week on this fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq.

Media Options