Topics

Guests

- Renée FeltzDemocracy Now! producer.

- Ramsey Clarka lawyer and former U.S. attorney general. He is urging the federal government to grant Lynne Stewart compassionate release from prison as she fights advanced stage cancer.

Support is growing for imprisoned attorney Lynne Stewart to be released early from prison due to her worsening health. Stewart’s prison warden has recommended to the Justice Department that she be released to the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. The 73-year-old imprisoned grandmother is fighting stage IV cancer that has metastasized, spreading to her lymph nodes, shoulder, bones and lungs. Stewart is serving a 10-year sentence in a federal prison near Fort Worth, Texas. In 2005, she was found guilty of distributing press releases on behalf of her jailed client, Egyptian cleric Omar Abdel-Rahman, also known as the “Blind Sheikh,” who is now serving a life sentence for conspiring to blow up New York City landmarks in 1995. We speak to former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark and Democracy Now! producer Renée Feltz, who is just back from Texas where she interviewed Lynne Stewart in federal prison, the first face-to-face interview granted to a reporter. The call for Stewart comes at a time when the Federal Bureau of Prisons is facing increasing criticism for refusing to release terminally ill prisoners. A recent report from the Justice Department’s inspector general found the bureau’s compassionate release program is “poorly managed and implemented inconsistently, likely resulting in eligible inmates not being considered for release and terminally ill inmates dying before their requests were decided.”

Transcript

AARON MATÉ: The Federal Bureau of Prisons is facing increasing criticism for refusing to release terminally ill prisoners. A recent report from the Justice Department’s inspector general found the bureau’s compassionate release program is, quote, “poorly managed and implemented inconsistently, likely resulting in eligible inmates not being considered for release and in terminally ill inmates dying before their requests were decided.” Over the past two decades, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has given compassionate release to about 500 prisoners, an average of about two dozen a year.

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show looking at the case of one prisoner seeking compassionate release: the longtime civil rights attorney Lynne Stewart. The 73-year-old imprisoned grandmother is fighting stage IV cancer that’s metastasized, spreading to her lymph nodes, shoulder, bones and lungs. She’s serving a 10-year sentence in a federal prison near Fort Worth, Texas.

Stewart was found guilty in 2005 of distributing press releases on behalf of her jailed client, Egyptian cleric Omar Abdel-Rahman, also known as the “Blind Sheikh,” who is now serving a life sentence for conspiring to blow up New York City landmarks in 1995.

In a minute, we’ll be joined by two guests to talk about Stewart’s health and a major update about her request for compassionate release. But first let’s hear from Lynne Stewart in her own words. This is a clip from 2009, when she spoke to Democracy Now! in her last broadcast interview before beginning her prison sentence. Lynne Stewart explained the background to the case and why she had been charged.

LYNNE STEWART: I represented Sheikh Omar at trial—that was in 1995—along with Ramsey Clark and Abdeen Jabara. I was lead trial counsel. He was convicted in September of ’95, sentenced to a life prison plus a hundred years, or some sort—one of the usual outlandish sentences. We continued, all three of us, to visit him while he was in jail—he was a political client; that means that he is targeted by the government—and because it is so important to prisoners to be able to have access to their lawyers.

Sometime in 1998, I think maybe it was, they imposed severe restrictions on him. That is, his ability to communicate with the outside world, to have interviews, to be able to even call his family, was limited by something called special administrative measures. The lawyers were asked to sign on for these special administrative measures and warned that if these measures were not adhered to, they could indeed lose contact with their client—in other words, be removed from his case.

In 2000, I visited the sheikh, and he asked me to make a press release. This press release had to do with the current status of an organization that at that point was basically defunct, the Gama’a al-Islamiyya. And I agreed to do that. In May of—maybe it was later than that. Sometime in 2000, I made the press release.

Interestingly enough, we found out later that the Clinton administration, under Janet Reno, had the option to prosecute me, and they declined to do so, based on the notion that without lawyers like me or the late Bill Kunstler or many that I could name, the cause of justice is not well served. They need the gadflies.

So, at any rate, they made me sign onto the agreement again not to do this. They did not stop me from representing him. I continued to represent him.

And it was only after 9/11, in April of 2002, that John Ashcroft came to New York, announced the indictment of me, my paralegal and the interpreter for the case, on grounds of materially aiding a terrorist organization. One of the footnotes to the case, of course, is that Ashcroft also appeared on nationwide television with Letterman that night ballyhooing the great work of Bush’s Justice Department in indicting.

AMY GOODMAN: Longtime civil rights lawyer Lynne Stewart. That was Lynne Stewart speaking on Democracy Now! in 2009 just before she began her 10-year prison sentence.

For more, we’re joined by two guests. Ramsey Clark, the former attorney general of the United States, he is urging the federal government to grant Lynne Stewart compassionate release from prison as she fights advanced stage cancer. Also joining us is Democracy Now!'s Renée Feltz. She's just back from Texas, where on Friday she was the first reporter to interview Lynne Stewart in person at the Federal Medical Center, Carswell, a federal prison located on the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base in Fort Worth.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Ramsey Clark, you just received a call from the Bureau of Prisons about Lynne Stewart?

RAMSEY CLARK: Yes. The general counsel for the bureau in Washington called yesterday to say that they had received the recommendation of the warden of the prison for compassionate release for Lynne. So that leaves it up to the director and Judge Koeltl, the judge. If all—if those join in the recommendation for her compassionate release, she’ll be released. And, of course, it’s an urgent matter because of advanced stage of cancer, which she’ll go straight to Sloan-Kettering.

AMY GOODMAN: Renée Feltz, you just saw Lynne Stewart on Friday. Can you talk about your meeting? Talk about her condition, how she looked.

RENÉE FELTZ: Well, Amy, to me, this is literally a story of life and death. This is a story of a woman we saw earlier in the show who was feisty, a little bit overweight, and full of life and vigor. When I saw Lynne approaching me when I first entered the federal prison on Friday for a pen-and-paper interview—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, “pen-and-paper”?

RENÉE FELTZ: Well, we had requested, because we’re a television and radio program, to do an on-camera interview or, at the very least, a recorded telephone interview. And we were told that for security reasons that request was denied. We’re currently appealing that. So, when I went to see her, I was only allowed to take in a notepad, and she wasn’t allowed to take in any notes herself, which she’s used to doing because, of course, she’s a lawyer and used to meeting with clients in prison and being able to refer to her notes.

But in terms of what I observed about her health, compared to previous people who have visited her, she seems to be going downhill rapidly. Like I was saying, this feisty woman that we’ve seen earlier in the show today in these clips, when I saw her, was now a 73-year-old woman who was thinner, who was wearing a knit cap because she had gone bald from former chemo treatments, and was using a walker to slowly approach me, and told me that basically she has to nap for an hour or so even to do something as simple as take a shower. She’s been telling her supporters that she won’t be able to reply to their letters right away because she’s needing to rest. And, in fact, she was wearing—she has been put into, originally, her own hospital room, because she had to be isolated from general population because of her low white blood cell count, if this indicates anything about her condition since receiving chemo.

The other thing that Lynne told me when I saw her on Friday about her health is that she has finished four chemo treatments. She didn’t actually begin those chemo treatments until about four months after she was told that her cancer had come back from remission. She originally had breast cancer in remission, and now it’s come back in two places in each—one place in each lung, in her back and then under her left armpit and her lymph node. And the chemo treatments she received were successful with the lymph node and the back, but her lung cancer did not respond to it. And so she still seemed pretty weak. And according to her, her physician is not even clear exactly what the next steps will be for her in terms of her treatment.

AARON MATÉ: Ramsey Clark, you’ve known Lynne Stewart for a long time, and you in fact brought this case to her about two decades ago?

RAMSEY CLARK: 1994.

AARON MATÉ: So tell us about this background. Why was this case important to you?

RAMSEY CLARK: Well, it was a major case in international terms. A internationally famous Islamic scholar, Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, had been indicted in the United States, and it was imperative that both the appearance and the fact of effective representation in court be made. Some people had come to me and asked me to do it or to find counsel. And over a period of time, I talked to people and finally thought of Lynne and thought it would be wonderful if a woman could do it.

She came in on a Saturday afternoon, and her husband Ralph came with her, said, “Don’t do it, Lynne,” prophetically. And she said, “I’ll do it if the judge will give more time,” because the case was set for about—it was a big case with 17 defendants—was set for about three months from this time, if the judge will give more time and if, on meeting the sheikh, he would accept her. The judge gave more time, and the sheikh met with her, and they became fast friends, actually. He accepted her.

AMY GOODMAN: And then talk about why Lynne Stewart is in jail. The sheikh was convicted.

RAMSEY CLARK: The government has introduced something called SAMs, special administrative measures, that prohibit or seek to prohibit an attorney from effective representation of a client by requiring confidentiality and prohibiting release of information, passing out statements from a client. And Lynne was charged with passing messages from the sheikh to the world through the media.

AARON MATÉ: And then later on her sentence was increased. After civil rights lawyer Lynne Stewart was convicted, she was sentenced to 28 months in prison. She was released pending appeal. Then she made a comment during a press conference outside the courthouse that seems to have played a key role in her sentence later being increased to 10 years in prison.

LYNNE STEWART: I don’t think anybody would say that going to jail for two years is something you look forward to, but as my clients have said to me, I can do that standing on my head.

AARON MATÉ: So there she is, speaking outside the courtroom, and so this added on, Ramsey Clark, 10 years to her sentence?

RAMSEY CLARK: It didn’t add on 10; it took the 28 months up to 10 years. They resentenced her. The court of appeals directed the district court that does the sentencing to reconsider the sentence, and a 10-year sentence was imposed.

AMY GOODMAN: How unusual is that, for a comment she made outside the courthouse?

RAMSEY CLARK: Well, I’ve been practicing law for longer than you want to hear about, and I’ve never heard of it happening before. But the SAMs, these special administrative measures, are a unique restriction on effective representation of counsel. They prohibit counsel from doing things that counsel are used to doing in defense of their clients.

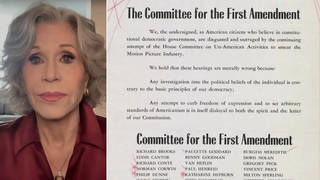

AMY GOODMAN: In addition to calling for her compassionate release from prison, Lynne Stewart’s defense team has filed a cert petition asking the Supreme Court to hear her case. It reads in part, “Freedom of speech does not exist in the abstract. It can only flourish in an effective forum. For, in reality, free speech is found in a multitude of circumstances. Not long ago it was young people, with long hair, tramping around a federal courthouse chanting, 'No. No. We won't go!’ It is an American flag sewn to a pair of old blue jeans. It’s all this and much more that defy description. It is indivisible. We cannot save it for one person and deny it to another. It must exist for all of us, or there is a real risk that, someday, it may not exist for any of us. And, so, it must exist for Lynne Stewart along with everyone else because her words are entitled to the same protection from prosecution as other political speech. Under no circumstances should her words and beliefs subject her to eight more years of imprisonment,” her defense team wrote. Your response, Renée Feltz, as you look at this case? And then talk about the government’s own report on compassionate release.

RENÉE FELTZ: Well, so, in addition to Lynne’s pending request for compassionate release, which I think has reached a major turning point based on the call that Ramsey Clark received on Monday, she has a—what they call a cert petition pending before the U.S. Supreme Court. And that’s basically arguing a First Amendment issue of free speech, as we just mentioned in that quote. And the crux of it is: Can someone who says something after they’re convicted outside of the courthouse—can that be used to then up their sentence after the sentence has already been issued? And there’s another argument that’s a little complicated and we won’t get into, but the government has asked for an extended period of time to reply to this cert petition, and until they do so, it won’t actually go before the U.S. Supreme Court. And based on Lynne’s lawyer Jill Shellow’s analysis, it probably won’t actually get to the court until later this fall. So, really, the compassionate release is what people are focusing on.

And in regards to this inspector general report that came out from the Department of Justice, essentially it’s arguing that the safety valve that exists for people who face extraordinary and compelling circumstances, such as a terminal illness like Lynne has, stage IV cancer in several parts of her body since the breast cancer has metastasized, in these cases, the Department of Justice found that the Bureau of Prisons is not responding promptly. They’re barely tracking the requests that they do receive. And they’re also basically having a mixed message in terms of what standards one has to meet.

Originally, Lynne had asked for compassionate release and was denied. She, in a short way of saying it, wasn’t close enough to death. Now, the warden at the prison where she’s being held has granted that, and it’s anybody’s guess exactly what criteria she really met. Since the Department of Justice issued this report, the Bureau of Prisons has since come out and said 18 months is the cutoff point. You have to be 18 months close to dying, essentially, in order for them to consider whether or not you’re eligible.

And one interesting thing, as a reporter, that I found is they don’t actually track the number of requests they receive or how long it takes them to go through the system. And apparently the Department of Justice has convinced the Bureau of Prisons to consider tracking that, so journalists like myself can see how many of these cases have actually been acknowledged. As we mentioned in the lede into this story, Human Rights Watch did a report in 2012 that found about 24 cases a year are acknowledged out of a population of about 200,000 people being held in Bureau of Prisons, so that’s a really low ratio of people having their requests for compassionate release granted. And finally, many of the requests have been taking so long to be processed that people die before they’re granted.

AMY GOODMAN: Ramsey Clark, you’re the former attorney general of the United States. When we called the prison, both Renée and I talked to the prison officials there Renée asked if she could go in and film Lynne Stewart, and they said, “No, that would be a security risk.” She could only take in a pen and paper, could not take in a camera. For our TV viewers, we’re showing images of Lynne, but that’s a prison photographer, and that wasn’t offered to us. When I called to ask if we could record the phone conversation—Renée had originally put in that request—they said, “Yes,” so that we would hear Lynne Stewart’s voice. But then they called me back and said, no, they’re sorry that we would not be able to record it. We could have a conversation, but we couldn’t record it. So, we wouldn’t be able to show Lynne, and obviously she’s very sick. We wouldn’t be able to broadcast her voice. What is the security issue here? I asked them—you know, we’re on the telephone—”What could possibly be the security issue?” And they said the warden had turned it down. Is it to not be able to hear a prisoner’s voice or see them?

RAMSEY CLARK: It just sounds like arbitrary and bureaucratic decision making. There’s no security risk that I can imagine. I don’t think anybody else can imagine one. You just—

AMY GOODMAN: Except that people would see, people would hear her, and that would what? Drum up sympathy?

RAMSEY CLARK: Well, that’s not a security risk. But it—nothing wrong with human sympathy. I’m all for it.

AARON MATÉ: What’s your assessment of her prospects to win this compassionate release?

RAMSEY CLARK: I think she’ll get compassionate release. There are two more stages in the process: the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons and Judge Koeltl, the district judge who initially sentenced her and resentenced her on the insistence of the court of appeals. And I see no reason for it not going through rapidly. It’s an urgent matter, obviously, because her health is tragically precarious.

RENÉE FELTZ: I would just add to that, briefly, Amy, since Lynne has entered prison, it’s estimated she has lost about 60 pounds. She’s strikingly thinner. She has sort of an ashen, a loss of color, look about her skin.

And as far as her prospects go, I spoke with her husband Ralph, and he mentioned something interesting to me. You know, when Lynne was convicted, she was disbarred, and she’s no longer able to practice law. While she’s been in prison, the prisoners there know that she’s been a lawyer in the past and occasionally ask her for advice. And while she tells them that she cannot offer advice as a lawyer, she sometimes answers some questions, does a spell check and things like this, tells them where to look in a law book. And for that, she may have received some demerits. And apparently, her husband told me that she was also helping a woman on dialysis to get more access to iron, vitamins and food, using her commissary, and this is against the rules, and that might also be a demerit. And, you know, Ralph’s question was: You know, is Lynne going to be punished for essentially helping others, and would this hurt her case for compassionate release? So, it remains to be seen how some of that is handled.

And in the meantime, essentially, I wanted to add one other thing from Jill’s lawyer—from Lynne’s lawyer, Jill Shellow. She noted that, you know, Lynne was sentenced originally to two-plus years in prison and then to 10 years, but she wasn’t sentenced to die in prison. And during her court case, Lynne’s lawyer asked the judge, “Do you want to see Lynne Stewart die in prison?” And the judge said, “No.” And I believe that that’s the same judge that’s now going to review this pending appeal for compassionate release.

Media Options