Guests

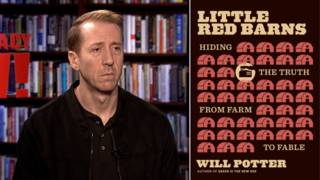

- Matthew Farwella writer for Rolling Stone magazine and an Afghan War veteran. He helped the late Michael Hastings write the 2012 article on Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl titled “America’s Last Prisoner of War.”

As the controversy over the prisoner swap grows, new information has emerged about Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl’s time in Afghanistan. On Thursday, administration officials said Bergdahl’s life could have been in danger if details of the prisoner swap had been leaked. While some in the media have speculated that Bergdahl became sympathetic to his captors, new reports reveal Bergdahl actually escaped from his captors on at least two occasions, once in the fall of 2011 and again sometime in 2012. In another development, The New York Times reveals a classified military report concluded Bergdahl most likely walked away from his Army outpost in June 2009 on his own free will, but it stops short of concluding that there is solid evidence that he intended to permanently desert. The report also revealed that Bergdahl had wandered away from assigned areas while in the Army at least twice before, prior to the day he was captured, including once in Afghanistan. We speak to Matthew Farwell, a journalist and veteran of the Afghan War who has been following the Bergdahl story for years. He helped the late Michael Hastings write his 2012 Rolling Stone article, “America’s Last Prisoner of War.” Farwell came to know Bergdahl’s parents after they attended the funeral of his brother, who served and in Iraq and Afghanistan and died in a helicopter accident in Germany.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: President Barack Obama said Thursday he would make, quote, “no apologies” for agreeing to a prisoner swap to free Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl in exchange for five Guantánamo detainees.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: I’m never surprised by controversies that are whipped up in Washington. Alright, that’s—that’s par for the course. But I’ll repeat what I said two days ago. We have a basic principle: We do not leave anybody wearing the American uniform behind. We had a prisoner of war whose health had deteriorated, and we were deeply concerned about it, and we saw an opportunity, and we seized it. And I make no apologies for that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The rescue of Bergdahl has touched off a political firestorm. On Thursday, administration officials said Bergdahl’s life could have been in danger if details of the prisoner swap had been leaked. Bergdahl had been held captive by the Haqqani Network for five years. While some in the media have speculated that Bergdahl became sympathetic to his captors, new reports reveal Bergdahl actually escaped from them on at least two occasions—once in the fall of 2011 and again sometime in 2012. According to The Daily Beast, in his first escape, Afghan sources said he avoided capture for three days and two nights before searchers finally found him, exhausted and hiding in a shallow trench he had dug with his own hands and covered with leaves.

AMY GOODMAN: In another development, The New York Times reveals a classified military report concluded Bowe Bergdahl most likely walked away from his Army outpost in June 2009 of his own free will, but it stopped short of concluding there is solid evidence he intended to permanently desert. The report also revealed Bergdahl had wandered away from assigned areas while in the Army at least twice before, prior to the day he was captured, including once in Afghanistan.

Well, we’re joined right now by Matthew Farwell. He’s a journalist and a veteran of the Afghan War who’s been following the Bergdahl story for years. He helped the late reporter Michael Hastings write his 2012 Rolling Stone piece headlined “America’s Last Prisoner of War.” Matthew Farwell came to know Bergdahl’s parents after they attended the funeral of his brother, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan and died in an accident in Germany.

Matthew Farwell, thank you so much for joining us.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Thank you for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: So why don’t you talk about how you met Bowe Bergdahl’s parents, Bob and Jani?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, I didn’t really meet them. I was up giving the eulogy for my brother and looked back in the back of the church and saw two people that I thought I recognized, and it was Bob and Jani Bergdahl.

AMY GOODMAN: Because you are from Idaho.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Because I was—my parents are from Idaho, and I had been following the news so closely.

AMY GOODMAN: What year was this?

MATTHEW FARWELL: This was 2010, ma’am, February 3rd.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, how did you then come to know them?

MATTHEW FARWELL: After that, I kept in touch with them a little bit, because I thought that was a classy gesture. And then Michael and I did the story, and I’ve stayed in touch.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in terms of the story with Michael, how did you decide to focus on the Bergdahl story and begin gathering the information, which is really the definitive work on the Bergdahl saga?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, you know, the FBI actually investigated how that came to be. So I’ve got to keep some trade secrets on it. But—

AMY GOODMAN: No, explain for a moment. I mean, this is a side story, but Michael died in a fiery car crash, and he had said at the time that he was being investigated by the FBI.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yes, and then a Freedom of Information Act request was done by a great journalist named Jason Shapiro. And it came back, and he sent it up to me, and I saw all the redacted portions and said, “Holy cow, they’re talking about me right here!” And so I put through a Privacy Act request, got it back, and, sure enough, they were looking into our, quote-unquote, “controversial” reporting on the story, which I think is a little unusual the FBI is reading Rolling Stone on the job. But I give them credit.

AMY GOODMAN: So tell us about Bowe Bergdahl and what you learned.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, you know, Bowe is an interesting guy. And I’m very conflicted myself about how I feel about him and his case. But he was a young man; homeschooled; grew up in Sun Valley, Idaho; from all accounts, very intelligent. He did a lot of traveling prior to joining the Army.

AMY GOODMAN: His parents came from California?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yes, ma’am. They came from California to Sun Valley, I think, the year before his older sister was born. And they stayed there ever since. His dad was the Sun Valley UPS man for 30 years. It’s hard to get more American than they are.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And as your story in Rolling Stone details, early on, he grew dissatisfied with being at home, being homeschooled, and decided he wanted to pursue a life of adventure. Could you talk about that?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right. I mean, you know, it seems he went up and worked as a commercial fisherman in Alaska. He traveled around the States on a motorcycle, you know, just all the sorts of things that young men who are seeking something seem to do.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the French Foreign Legion, too?

MATTHEW FARWELL: And, yeah, and his father said that he had tried to join the French Foreign Legion and was disqualified for eyesight.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what that is, the French Foreign Legion.

MATTHEW FARWELL: The French Foreign Legion is France’s force of essentially foreign mercenaries, who can come from any walk of life. A lot of them are hardened criminals or refugees currently from Eastern Europe. And once you join, you acquire a nom de guerre, you know, a fake name that you get for them.

AMY GOODMAN: Bowe was known around town in Hailey, Idaho. He worked at Zaney’s coffee house. He took up ballet, and many had seen his performances.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yes, ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how does he end up in the U.S. military? How does he end up in Afghanistan?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, he didn’t just end up in the U.S. military. He ended up in the U.S. Army Parachute Infantry. And so, it’s—you know, the military, about 90 percent are support personnel; about 10 percent are the actual war fighters and trigger pullers. And so he was in that 10 percent. And it seems he just came back one day and said, “Hey, dad, I’m thinking about joining the Army.” And as we said in the story, “Are you thinking about joining the Army, or did you already sign up?” And Bowe kind of admitted, “Well, yeah, I already signed up.” And so, it’s a path, you know, a lot of young men take. I took it, dropped out of the University of Virginia to join the infantry. And aside from that, I don’t know.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But now, your article paints a not very flattering portrait of the unit that he was assigned to and of the problems he had with the lack of discipline and the lack of actual fighting capacity of the unit that he was in, in an outpost, really, in Afghanistan. Could you describe some of those problems?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, you know, it seems—from the video that Sean Smith of The Guardian shot after embedding with them for about a month, it seemed to me, as a former infantryman who served in that exact area and knows that ground very, very well, that the unit wasn’t operating with the same level of professionalism that’s required to stay on your game there and keep your men alive and keep your men, apparently, from walking off.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to Sean Smith’s—a clip of Sean Smith’s first film. He’s The Guardian reporter, and he was embedded with Bowe’s unit. And then, because he had come to know this unit, the Bergdahls said he could come to Idaho, and he did a 12-minute piece about Bob Bergdahl.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let me go to that piece right now, just a clip of Sean Smith. He is talking to—not Bowe, but it’s other soldiers who are talking here.

SOLDIER 1: These people just want to be left alone.

SOLDIER 2: Yeah, they got dicked with—they got dicked with from the Russians for 17 years, and then now we’re here.

SOLDIER 1: Same thing in Iraq when I was there. These people just want to be left alone, have their crops, weddings, stuff like that. That’s it, man.

SOLDIER 2: I’m glad they leave them alone.

SEAN SMITH: A few weeks later, Bowe Bergdahl, pictured in this photo, disappeared. The circumstances are unclear.

AMY GOODMAN: That, a report from The Guardian from Sean Smith, embedded with Bowe Bergdahl’s unit. Now, according to your piece, the piece that you wrote with Michael Hastings in Rolling Stone, Matthew, Bowe sent a final email to his parents on June 27, three days before he was captured in 2009. He wrote, quote, “The future is too good to waste on lies. … And life is way too short to care for the damnation of others, as well as to spend it helping fools with their ideas that are wrong. I have seen their ideas and I am ashamed to even be american. The horror of the self-righteous arrogance that they thrive in. Is is all revolting. I am sorry for everything here. … These people need help, yet what they get is the most conceited country in the world telling them that they are nothing and that they are stupid, that they have no idea how to live. The horror that is america is disgusting.” He also saw a U.S. military vehicle roll over an Afghan baby. Matthew Farwell?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, I mean, I think that pretty much speaks for itself. The guy was clearly not happy where he was, not happy with the people he was serving with. And, you know, that area is a bad, bad area that he walked off from. And it’s just difficult for me to comprehend what must have been going through his mind when he made that decision, because I’ve been through there, and I was scared out of my mind, you know, walking through that town. And some of the guys that were with, you know, intelligence units always told us, “Hey, watch yourself when you’re in Yahya Kheyl.”

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s be clear: He had packed up his stuff, sent it to his parents, and left his gun, his body armor, everything at the outpost, and then he went and left.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right. From what we’ve heard, he only took a bottle—couple bottles of water, his books, and—I’m trying to think what else—a knife and his camera. And some of the reports that came through the WikiLeaks disclosures indicate that that’s what the Afghan villagers saw when they saw him, you know, walking by himself. And the Afghan villagers thought that was crazy.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you were—as you say, you were in the same area of Afghanistan. What is your sense of the level of the kind of disillusionment that Bowe Bergdahl expressed here? How prevalent was that, or is that an isolated situation, or was there a sharp degree of disconnect between what the soldiers came there thinking they were going to do versus what they ended up doing?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, you know, like I’ve said, the area was a very difficult area to operate in, you think. It’s crushing poverty, zero percent female literacy, literally no toilets in the entire province, except for American toilets. And so, a lot of the men in my platoon—I was there two years prior to Bowe being there, and a lot of the men in my platoon, myself included, came back with tremendous cases of PTSD from what we were doing there, because it was simply a difficult place to fight a war in. And I think everyone from Alexander the Great up to the Soviets to us have learned that fact the hard way.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break and then come back to this discussion. We’re talking with Matthew Farwell. He is a writer for Rolling Stone magazine, an Afghan War veteran, helped the late Michael Hastings write the 2012 article on Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl that’s become the definitive piece on him, called “America’s Last Prisoner of War.” Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. And our guest is Matthew Farwell. He served in the military in Afghanistan, like Bowe, two years before him. He met the Bergdahls when they came to his brother’s funeral, who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan and died in service in Germany. We’re going to turn now to the media’s focus on the Bergdahl family, particularly his father Bob. I wanted to turn to comments made by MSNBC host Joe Scarborough on his show on Thursday, responding to the email exchange between Bowe Bergdahl and his father, published in Michael Hastings’ and Matthew Farwell’s piece in Rolling Stone.

JOE SCARBOROUGH: If my son—I’ve got a 26-year-old son, and if my son is out on the wire, and he is out there with fellow troops, and he writes me up and says he hates America and he’s thinking about deserting and he’s thinking about leaving his post, I can tell you, as a father of that 26-year-old or 23-year-old son, I’d say, “Joey, you stay the hell right there.” I would call his commander. I would say, “Get my son. He is not well. Get him to a military base in Germany.” I would not say, “Follow your conscience, son!” I would not reach out to the voice of jihad!

AMY GOODMAN: Can you respond to this, Matthew Farwell, if you could understand it? It’s Joe Scarborough shouting at the MSNBC reporter Chuck Todd.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yeah, I’m stunned by that. That’s the first time I’ve seen that clip. And I—you know, I was doing a lot of press yesterday about this, and I’m just astounded that all these people that, you know, didn’t know a thing about this case for the past five years have all of a sudden become experts, you know? No one cares until there’s something to politicize and a soundbite to be made.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about this—the whole issue of the criticism that has been leveled against Bowe Bergdahl by his former fellow soldiers. As your article points out, the military, for years, insisted that no one talk about his case—

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —and no one say anything public about this case. And now, suddenly, you’re getting this enormous outpouring of comments, a lot of it orchestrated by a Republican operative who has been producing some of these soldiers for the media.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yeah, and, you know, that was one of the biggest things that disturbed me so much about this whole story and that really got me thinking it must be something, is it’s unprecedented to have an entire brigade—3,500 people have to sign a nondisclosure agreement about pretty much their entire tour in Afghanistan when they come back home. And so, these guys have bottled up this emotion. I’ve spoken with them.

AMY GOODMAN: But explain that, signing a confidentiality agreement to protect? I mean, what was the reason given?

MATTHEW FARWELL: The official reasons was that if they said anything about Bowe Bergdahl, it could, you know, hurt him or possibly cause him to be further mistreated by the Taliban or the Haqqani Network. But, to me, having served in the Army both as a trigger puller and then as a desk jockey at a four-star general’s headquarters, it seemed like it was an exercise in covering the Army’s butt and, you know, trying to not make themselves and this war look as bad as it was.

AMY GOODMAN: You talk about the soldiers being told not to say anything—

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: —having to sign confidentiality agreements. What about the media?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, that’s the other funny thing, is how complicit the media was with this. I’ve spoken with the White House official that was in charge of coordinating the media response and kind of ensuring that no one in the media spoke out or wrote about this. And frankly, you know, he managed to snow a lot of the people in the media, and that’s why I’ve got to give so many props to Michael Hastings, who I wish were sitting in this chair instead of me, and to Rolling Stone for have the guts to go after this story and to really tell it like it needed to be told.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to your media appearances. You were on CNN yesterday. And I wanted to go to this clip. This is when you were being interviewed by a CNN host, Carol Costello.

CAROL COSTELLO: Why did he grow his beard out?

MATTHEW FARWELL: So that he would have some sympathy with the people that were holding his kid hostage.

CAROL COSTELLO: And this was not really an attempt to become a member of the Taliban; it was more to convince them that, you know, hey, maybe I can see things your way so that my son will be released, but he didn’t really mean that? Is that the sort of thing that we’re talking about?

MATTHEW FARWELL: No, so that his son would be treated decently. I mean, remember, you’re talking about a family that every night goes to sleep thinking their son might be tortured every day. Can you imagine what that must be like? I can’t, and I’ve lost a brother in the war, and I’ve fought in the war.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s our guest today, Matthew Farwell, yesterday on CNN, a former soldier from Idaho who served in Afghanistan. At the end of the clip, the text on the screen read: “Bergdahl’s father accused of looking Muslim.” Now, you don’t see that because you’re just on air, but that’s what the lower third, as we call it, said: “Bergdahl’s father accused of looking Muslim.”

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, right, which I’m not sure when that became a crime in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, in any of these cases, you just replace it for your own religion, right? “Bergdahl’s father accused of looking Jewish. Bergdahl’s father accused of looking Catholic.”

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, it seems pretty racist to me.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk about the deleted email of Bob Bergdahl a few days before he—his son was released. The media has made something of this. He—just to say what that deleted tweet was that he said—I think it was a day or two before his son was released.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, I believe that tweet said something about still working to free all the prisoners in Guantánamo Bay, or something to that effect. And he’s really taken a lot of criticism for it. But, look, you’ve got to think about this. Bob and Jani Bergdahl have lived every day of their lives for the past five years thinking it might be their only son’s last day. You know, I think we, as Americans, can probably cut him a little bit of slack.

AMY GOODMAN: The tweet said, “I am still working to free all Guantanamo prisoners. God will repay for the death of every Afghan child, ameen!” he said, Arabic for “amen.” The tweet was subsequently deleted.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right. And so, you know, at that point, their son was still in captivity, and Bob was doing everything he could think of to try and get his kid back. You know, my own father, who is the most staunchly conservative person you’ll ever meet and who’s a wonderful guy, said he would shave his head, you know, and go skinny dip and then kiss the president’s rear to get me back if I ever went missing. And so, you know, that’s a father’s love for his son, and I think it’s unfair to judge somebody too harshly for that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to turn, if we can, to some of the comments by some of the former soldiers that were stationed in Afghanistan with Bergdahl. I think we have the comment of the team leader, Evan Buetow, who was interviewed and who said that—Buetow said that the intercepted communication days after his disappearance showed that Bergdahl actively sought to communicate with the Taliban.

EVAN BUETOW: The American is in Yahya Kheyl. He is looking for someone who speaks English so he can talk to the Taliban. And I heard it straight from the interpreter’s lips as he heard it over the radio. And at that point, it was like, this is—this is kind of snowballing out of control a little bit. There’s a lot more to this story than just a soldier walking away.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But we also have now reports from The Daily Beast that he tried to escape twice from the Taliban when he was in captivity. Your response to some of these statements now by some of his fellow soldiers?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, first of all, those—the comments that his team leader said, I can’t verify or, you know, confirm or deny them. I can say that they were not reflected in the documents I reviewed that were released by WikiLeaks, that said—and I read some of the same ones that seemed to have the same thing—that there’s an American, he’s looking for someone who speaks English, but there was no mention that he was looking to join the Taliban.

And, you know, these guys, they’ve been under enormous strain, too, for the past five years, because they haven’t been able to talk about what is probably one of the most defining moments of their lives: going to war as a young person. And the men that I’ve spoken with from this unit, I mean, they took the fact that Bergdahl left, and then the fact that they had to spend the rest of their deployment, they felt, looking for him—they took it really hard. And that’s entirely understandable. And, you know, I’m not sure how I would have taken it if somebody in my unit had walked off. And so, I think they’re, at this point, just unleashing as much of this pent-up frustration and emotion as they have. And they’ve earned every right to do that. And I applaud them for finally coming out and being able to talk.

AMY GOODMAN: And there were suggestions of mismanagement of the team, [Buetow], who we just saw, being the team leader. On Wednesday, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina questioned the motive and timing of Bowe Bergdahl’s release.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: You’ve got to understand what’s going on. They had a Rose Garden ceremony with the man’s parents. I think the White House was looking at a twofer: to announce in one week that we’re going to withdraw from Afghanistan, ending the longest war in U.S. history, and, oh, by the way, as commander-in-chief, I secured the last captive of that war, the only captive of that war. That was thought, in their mind, I think, to be a pretty good political story for that week. It blew up in their face. So the question is: Was this release designed to enhance the announcement, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, getting the one guy back, or was it based on a circumstance that was so compelling, this was the moment and only this moment? That’s what we need to investigate.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Senator Lindsey Graham. Your response?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, you know, I’ve got a couple of things to say about this. The first thing is, they could have gotten him back two years ago for the exact same terms, this exact same deal. And Congress dithered. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee dithered. And we wrote about that in the article. And second, I think it’s pretty clear that the White House blundered this. You know, I mean, they got Bowe back, which—he’s an American soldier. Regardless of anything else, he is our guy. We bring him back, and then we deal with him, as appropriate, after that. We don’t just leave him in the hands of the Taliban, as so many people on Capitol Hill seem willing to do for the sake of political expediency.

AMY GOODMAN: Why two years ago did they not follow through with this? Secretary of state was Hillary Clinton at the time.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Secretary of state was Hillary Clinton, and secretary of defense was Robert Gates. And it’s my feeling that both of them, who would legally have to sign off on the deal, didn’t want to do it. And I believe—you know, I don’t know Mrs. Clinton’s motivations for that, and I don’t know Robert Gates’s motivations for that, but I know they also faced some pressure from really some hard-line chickenhawks in Congress, like Senator Saxby Chambliss, that they encountered quite a bit of pushback.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, of course, the atmosphere in Congress—between the Congress and the White House has only become more poisoned and even more combative in the period since then. I think The New York Times, in their editorial today, essentially said President Obama will face criticism from Congress for whatever he does. He would have faced criticism if he didn’t succeed in bringing Bergdahl back, and he would—and now he’s facing criticism for bringing him back.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Yeah, it’s actually really interesting and disgusting, in the same way, how a lot of the same people that were loudly clamoring for his release, when it appeared to be to their political benefit to do this, are now loudly condemning it. And I read it—

AMY GOODMAN: Because then it was opposing President Obama.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, because then it was something to slam the White House with, and now it’s something, again, to slam the White House with.

AMY GOODMAN: And Senator McCain has been most astounding, because he has been on videotape, right—he’s been on the shows demanding Bowe Bergdahl’s release and saying he’d agree to a prisoner swap, and this was the same prisoner swap that was offered two years ago, and now criticizing that very thing.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you get the emails, Matthew?

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, again, that’s part of the sources and methods of being an investigative journalist, and I would rather not talk about that.

AMY GOODMAN: But you stand by those emails—

MATTHEW FARWELL: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: —that Bowe sent to his family.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was his family’s response? You’ve talked to his family.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: In this piece by Sean Smith, the video piece following Bob Bergdahl, Bowe’s dad, it’s a stunning piece as he follows him into the woods, where he makes a fire and says Bowe spent a lot of time here, and he’s listening to Dr. King give his speech against the war in Vietnam. You hear some of the call to prayer in the background. And his father was learning Pashto, as he showed in Boise, Idaho, when he addressed his son at what was called a news conference, though they didn’t take questions, and said, “Bowe, I am your father.”

MATTHEW FARWELL: Right, right. I mean, the family’s response has been really interesting and compelling for me to follow, because, you know, here are two people that are in one of the most beautiful places on Earth, Sun Valley, Idaho, where the billionaires go to ski and hang out, living a pretty idyllic life. And then overnight, it all changes. They find out that their son is a prisoner. We wrote in the story that, you know, Jani Bergdahl heard her dog barking outside, her dog named Rufus, and saw two men come up wearing Army uniforms. And, you know, my own parents know what that’s like. And her heart just sank. And they said, “Well, it’s not the worst news, but we can’t tell you alone yet. Let’s get you with your husband.” And they’ve been living in that same sense of just heartwrenching anxiety ever since. And I can’t imagine the hell they’ve gone through over the past five years.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Have you had a chance to talk with them since the news of the exchange broke?

MATTHEW FARWELL: I haven’t, no. No, I’ve reached out to them, and—you know, but I’m respecting their privacy for now, and I imagine they have a lot more important things to deal with than talking to me.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Matthew Farwell, we want to thank you for being with us. It’s an astounding piece that you did with Michael Hastings. I don’t even know if he was being called a POW by the U.S. government at the time that you wrote this.

MATTHEW FARWELL: Well, technically, anyone is called a—listed as missing/captured nowadays, so the designation POW is somewhat bureaucratically obsolete.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Matthew [Farwell] is also a writer for Rolling Stone magazine and an Afghan War veteran, his family from Idaho. He helped Michael Hastings write the 2012 article on Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl headlined “America’s Last Prisoner of War.” We’ll link to it at democracynow.org.

When we come back, we deal with the second controversy around Bowe Bergdahl’s release, and that is the controversy of the prisoner swap. We’ll speak with one of the lawyers for one of the five men who were just released to Qatar, and we’ll speak with a reporter who has been covering Guantánamo for years. Stay with us.

Media Options