Related

Guests

- Costas Panayotakisprofessor of sociology at the New York City College of Technology at CUNY. He is the author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.

After a historic victory in Greece, the leftist Syriza party’s finance minister has begun a tour of Europe to push an anti-austerity message. The former economist Yanis Varoufakis has promised “radical” change as his government seeks to renegotiate Greece’s huge debt obligations and to roll back key parts of its international bailout. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras says he is confident that Greece can reach a deal with creditors. We air an excerpt of our 2012 interview with Varoufakis and speak with Costas Panayotakis, a professor of sociology at CUNY and author of “Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.” Panayotakis lays out the Syriza party’s historic rise to power and the challenges it faces in trying to restructure Greece’s economy.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: After an historic victory in Greece one week ago, the leftist Syriza party’s finance minister has begun a tour of Europe to push an anti-austerity message. The former economist, Yanis Varoufakis, has promised radical change as his government seeks to renegotiate Greece’s huge debt obligations and to roll back key parts of its international bailout. After talks in France this weekend, he’s set to meet with his counterparts in London today and in Rome later this week. On Saturday, Varoufakis said he wants to wean his country off of loans.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS: Do I believe that Greece, as we are now, should be taking another tranche of loans? No. It’s not that we don’t need the money. We are desperate because of certain commitments and liabilities that we have. But my message to our European partners is that for the last five years Greece has been living for the next loan tranche. And as I said to Mr. Sapin, we have resembled drug addicts craving the next dose. What this government is all about is ending the addiction.

AMY GOODMAN: Varoufakis said Greece was, quote, “desperate” for money. But he insisted it would not seek a seven billion [euro] installment on its 240 billion euro bailout package, because that would require the country to adhere to austerity measures. This comes as the new Greek prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, said he was confident Greece could reach a deal with creditors. Meanwhile, on Sunday, President Obama made his first comments on Greece’s election outcome during an interview on CNN.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: You cannot keep on squeezing countries that are in the midst of a depression. At some point, there has to be a growth strategy in order for them to pay off their debts, to eliminate some of their deficits.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, for more on the historic developments in Greece and what they could mean for the rest of Europe, we’re joined by Costas Panayotakis, associate professor of sociology at New York City College of Technology at CUNY. He returned to Greece last week to vote in the election, has been following the developments closely. He’s the author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Costas. Can you talk about this election? You went back to Greece to vote?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I was there for the winter, before the election date had been set, and I extended my stay because it was a historic moment. For the first time in Greece, a party of the left had won power. And in Greece, this is a big deal, because Greece has had a civil war just, you know, after World War II, and the fact that many mainstream people, who traditionally have nothing to do with the left, actually voted for the first time for the left shows how dire the situation has become and how desperate the people have become for change.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it’s just a clear-cut vote against austerity?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think so. I think these people had had enough. It was—people said enough is enough. And the policies that have been followed made the conservative party, mainly, and the socialist party, lose the people in the middle class, which has been decimated by these policies, so they lost much of their base.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain what the Syriza party is, what even that word means?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah. Syriza is an acronym, which in Greek means “coalition of the radical left.” So, it’s a coalition that grew out of the anti-globalization movement in the late ’90s. The sort of—the most important component of the party goes back to the sort Eurocommunist movement of the 1970s. And over the time, it has become the voice against austerity in Greece. And in a matter of just, you know, three years, it rose meteorically from a small party that barely made it into Parliament to getting 36 percent of the vote in the recent election.

AMY GOODMAN: Is this their first victory?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, well, they won the European elections last May, but this is their first parliamentary—victory in parliamentary elections. This is the first time they will assume power.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain what they’ve promised to do.

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, what they want to do is basically to stop the austerity program that was imposed on Greece in 2010 and to roll back many of the structural changes that came with that, because this austerity program is not just about budget cuts and, you know, eliminating the budget deficit, it’s also about restructuring Greek society and Greek economy towards a sort of free-market, neoliberal model that basically has led to the crashes of 2008 around the world and that has led to, you know, increasing inequalities around the world and in Greece.

AMY GOODMAN: Greece’s new finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, is an economics professor who once described the EU-imposed austerity measures as “fiscal waterboarding.” During an interview on Channel 4 in Britain, he vowed to destroy the Greek oligarchy.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS: Freedom of speech in Greece has been jeopardized by this unholy alliance between bankrupt bankers, developers and media owners, who become the voice of those who want to sponge and scrounge off everyone else’s productive efforts.

PAUL MASON: And what will you do to the oligarchy concretely?

YANIS VAROUFAKIS: We are going to destroy the basis upon which they have built, for decade after decade, a system and network that viciously sucks of the energy and the economic power from everybody else in society.

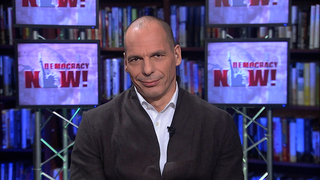

AMY GOODMAN: Well, back in 2012, Yanis Varoufakis appeared on Democracy Now! and commented on the political situation in Greece at the time.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS: Greece is going through its Great Depression, something akin to what the United States went through in the 1930s. This is not just a change of government. It’s a social economy that has entered into a deep coma. It’s a country that is effectively verging to the status of a failed state. Greece is going through an existentialist crisis. And just look at the numbers. The socialist party had 44 percent of the vote only two short years ago. It went down to 13 percent. The opposition, conservatives, they were at the low tide mark of 35 percent, 35 percent in 2009. They would have been in a position they should be picking up votes. They went down below 20 percent. The political class of Greece, effectively, has been thrown out by the electorate. This is very exciting and very worrying at the same time. The rise of the Nazis is something to be lamented.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s today’s finance minister. Costas, if you could respond?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think this—his interpretation of what happened in the May 2012 election is accurate. Already people had expressed their dismay, their sort of anger with austerity at that time. But what happened in the election that followed immediately in June, basically, the conservative party managed to get power through scare tactics, by basically threatening people that if the left won, Greece would be thrown out of the eurozone. And they tried the same tactic in this recent election, but it didn’t work as well for them this time around.

AMY GOODMAN: Greece’s new prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, has promised radical change as his government begins to roll back key parts of Greece’s international bailout. The government has put off the planned sale of the country’s biggest power utility, while pledging to raise pensions for those on low incomes and reinstate some fired public-sector workers. This is George Katrougalos, the new deputy minister of public administration.

GEORGE KATROUGALOS: It is the reforms, but the reforms that the country needs, not the reforms that are dictated from outside its borders. We must restart the economy. We must reinvigorate democracy. It is a big challenge, but I think we are fit to it.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell us who the new prime minister is?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah. His name is Alexis Tsipras. He’s a young, very charismatic politician. And he has been able to unite the party. This was a party that in the past had sort of suffered from a lot of infighting. And it has managed to basically steer the party towards a credible alternative to the policies of austerity that have devastated Greek society.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go back to President Obama’s comments on Greece during his interview Sunday on CNN.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: There is no doubt that the Greek economy was in dire need of reform. Tax collection in Greece was famously terrible. I think that there—in order for Greece to compete in the world market, that they had to initiate a series of changes. But it’s very hard to initiate those changes if people’s standards of livings are dropping by 25 percent. Over time, eventually, you know, the political system, the society can’t sustain it.

So, my hope is, is that Greece can remain in the eurozone. I think that will require compromise on all sides. When the financial crisis in Greece first flared up several years ago, we were very active in trying to arrive at some sort of accommodation. I think there’s a recognition on the part of Germany and others that it would be better for Greece to stay in the eurozone than be outside of it.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s President Obama. Costas Panayotakis, your response?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think this was a welcome intervention, and it signifies, I think, the rifts that have existed with—that are developing within Europe and between Europe and outside partners. There’s a growing recognition within Europe and in the U.S. that the austerity strategy preferred by the German political class is not working, and in fact it is threatening to drag down the global economy. So, there are growing rifts within Europe. There is rift between Germany and France and Italy, which are also trying to resist the prioritization of deficit reduction above all else. So, this—and, of course, there’s the rift between the political elites and people around Europe, who are sort of getting inspiration from Syriza. And we have other movements—the rise of the left in Spain, in Ireland. So, I think there is an opening that has been created, and it’s up to the European left and the social movements there to take advantage of it.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras speaking last week.

PRIME MINISTER ALEXIS TSIPRAS: [translated] We did not come here to take over institutions and to enjoy the trappings of power. We have come to radically change the way in which politics and governance is carried out in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Costas, if you could respond to what the prime minister said?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think what his—his main point, basically, is that, you know, austerity—a new way has to be attempted. And I didn’t hear the whole thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, he basically said, “We did not come here to take over institutions and to enjoy the trappings of power.”

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: “We have come to radically change the way in which politics and governance is carried out in this country.”

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I mean, the rise of Syriza signifies the bankruptcy of the political class in Greece, which has been—for very long, it has been very close to the Greek oligarchy, which has contributed to the crisis by not basically paying its fair share when it comes to taxes. So, what he wants to signify is that he wants to do things differently and to counter the cynicism that exists among many Greek voters, who have seen progressive parties in the past win elections—for example, the socialists back in ’81—and then they saw these parties basically disappoint, become corrupt, and corrupted by power.

AMY GOODMAN: Last week, Greece’s new prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, visited a World War II National Resistance Memorial in his first outing as the country’s new leader. The memorial is located at the site where the Nazis executed 200 Greek communist resistance fighters in May 1944. During the recent campaign, Tsipras called on Germany to pay Greece reparations for damages incurred during the Nazi occupation. A 2013 governmental study determined Germany owed Greece an estimated $200 billion. What’s the significance of this?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think this is a way of signifying that, you know, Germany owes to Greece, in many ways, as much as Greece owes to Germany. I think it’s also part of the strategy. One of the proposals that Tsipras and Syriza have made is that what is needed is a conference, a European-wide conference, that would deal with European-wide debt and allow countries to basically stand on their feet by basically writing off debt, much as Europe and the U.S. did to Germany in 1953. So I think it’s a way of signaling, pointing to the history that exists behind the rise of Germany and the way that Germany was able to stand on its feet after the World War II by basically the rest of the world being generous towards it. And, you know, I think the feeling in Greece and Syriza is that, you know, something similar has to be done on a European-wide scale if this ongoing crisis is to be overcome.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Panayotakis, talk about the creditors and what they will do now. Who are they?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, at the beginning of the crisis, the creditors were mainly—you know, it was the private sector, European banks. In many ways, the bailout, even though it was presented at the time as a bailout of profligate and lazy Greeks, it was really a bailout of European banks. Now, there has been already a restructuring of the Greek debt. And by now, most of the debt is held by the different European countries, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. So, basically, one of the complications is, there is a lot of resistance to writing off the Greek debt, because, of course, the governments of European countries would have to deal with, you know, the discontent by their voters if money was to be lost. But at the same time, basically, what Syriza and other powers of—rising powers of the left in Europe are saying is that, ultimately, when you have debt that is not sustainable, this will hobble your economic performance forever, and you will not be able to grow. And if you don’t grow, you will not be able to repay your debt.

AMY GOODMAN: Very quickly, the media coverage of the elections?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, the media coverage in Greece was interesting because there was a lot of fearmongering by the media that was controlled by the oligarchs. I think there was a lot of fearmongering in the 2012 election. The Financial Times at the time had an article in its first page in Greek to try to dissuade voters from voting for Syriza. I think this time around there was some fearmongering by international media, but it was a little more balanced. I think people had come to accept the fact that Syriza was going to probably win. And Syriza has and Tsipras had tried to sort of tone down his rhetoric as a way of reassuring people outside Greece that he was not an enemy of Europe, but was trying to try a different strategy so as to—that would be more effective than the strategies that have been attempted so far.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Costas Panayotakis, thanks so much for being with us, professor of sociology at the College of Technology at the City University of New York. He’s the author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.

When we come back, Peter Greste, the Al Jazeera journalist, one of three Al Jazeera journalists in jail in Egypt, has been freed. We’ll talk to Reporters Without Borders. Stay with us.

Media Options