Guests

- George Mitchellformer Democratic senator from Maine. He served as the U.S. special envoy for Middle East peace under President Obama from 2009 to 2011.

George Mitchell, the former senator and U.S. special envoy for Middle East peace under President Obama, joins us to discuss the escalating U.S.-Israel standoff over Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s campaign against an Iran nuclear deal and open rejection of the two-state solution. Last week, it emerged Israeli intelligence spied on the Iran talks and then fed the information to congressional Republicans. Obama and other top officials have vowed to re-evaluate their approach to the Israel-Palestine conflict following Netanyahu’s vow to prevent a Palestinian state. U.S. officials have suggested they might take steps, including no longer vetoing U.N. Security Council resolutions critical of Israel. A first test of the new U.S. approach might come in the next few weeks when France will put forward a U.N. Security Council measure aimed at encouraging peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Mitchell headed the U.S. role in the Mideast talks between 2009 and 2011. He previously served under President Bill Clinton as the special envoy for Northern Ireland, where he helped broker the Belfast Peace Agreement of 1998.

Transcript

AARON MATÉ: As historic talks over an Iran nuclear deal have reportedly closed ahead of a U.S.-imposed deadline, the Israeli government continues to oppose a deal. Last week, it emerged Israeli intelligence spied on the Iran talks and then fed the information to congressional Republicans. Now, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu says the deal’s proposed terms are even worse than he thought. Speaking on Sunday, Netanyahu appeared to invoke the “axis of evil” moniker used by President George W. Bush for Iran, Iraq and North Korea. But Netanyahu offered a new variation on the axis members.

PRIME MINISTER BENJAMIN NETANYAHU: [translated] I expressed our deep concern toward this deal emerging with the Iran nuclear talks. This deal, as it appears to be emerging, bears out all of our fears, and even more than that. The Iran-Lausanne-Yemen axis is very dangerous to humanity, and this must be stopped.

AARON MATÉ: The Lausanne in that axis refers to the Swiss town where the nuclear talks are taking place. That apparently puts the U.S. inside the axis that Netanyahu opposes, along with the five other world powers negotiating with Iran.

AMY GOODMAN: Netanyahu’s comment was the latest in an escalating standoff with the White House over Middle East policy. President Obama and other top officials have vowed to re-evaluate their approach to the Israel-Palestine conflict following Netanyahu’s open rejection of a two-state solution. U.S. officials have suggested they might take steps including no longer vetoing U.N. Security Council resolutions critical of Israel. Some predict a major shift in U.S. policy. A headline in The Washington Post describes it as, quote, “Obama’s next earthquake.” And the first test of the new U.S. approach might come in the next few weeks. France will put forward a U.N. Security Council measure aimed at encouraging peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. The measure would include parameters for negotiations, presumably based on an Israeli withdrawal from the Occupied Territories and the establishment of a Palestinian state there.

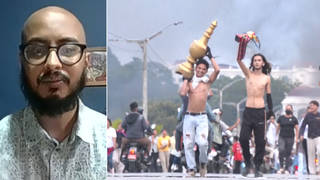

For more, we go to a guest who’s been deeply involved in U.S. efforts to seek a peace deal between Israel and Palestine. Senator George Mitchell served as U.S. special envoy for Middle East peace under President Obama from 2009 to 2011. He previously served under President Bill Clinton as the special envoy for Northern Ireland, where he helped broker the Belfast Peace Agreement of 1998. Before that, Senator Mitchell served as Democratic senator from Maine for 15 years, including as Senate Majority Leader from 1989 to 1995.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Senator Mitchell. Let us start on this issue of proposed measures President Obama and the administration is considering possibly against Israel, particularly what might happen in the United Nations.

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, I don’t think it’s possible to know. I doubt very much that any decision finally has been made within the White House. I think it’s all under review, as the president has said. It will depend, obviously, in part on the circumstances that exist at the time any such resolution is introduced at the United Nations, what the language of the resolution is, what the reaction both within the United States and among our allies is. I do think that the president is appropriately reviewing our policies, given the developments of the past few weeks, particularly the various statements of Prime Minister Netanyahu. But I don’t think anyone should draw any final conclusion from the discussions that are now underway, particularly since we don’t yet know what’s going to happen with the talks with Iran, which is obviously a major factor.

AARON MATÉ: But, Senator Mitchell, can we agree that this would be a major shift if the U.S. starts supporting or not blocking critical measures at the U.N.? I want to go first to a clip from U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power. Speaking about a year ago, she said the U.S. will continue to block Palestinian efforts in forums like the U.N.

AMBASSADOR SAMANTHA POWER: There are no shortcuts to statehood, and we’ve made that clear. Efforts that attempt to circumvent the peace process, the hard slog of the peace process, are only going to be counterproductive to the peace process itself and to the ultimate objective of securing statehood, the objective that the Palestinian Authority, of course, has. So, we have contested every effort, even prior to the restart of negotiations spearheaded by Secretary Kerry. Every time the Palestinians have sought to make a move on a U.N. agency, a treaty, etc., we have opposed it.

AARON MATÉ: Power went on to say that trying to, quote, “deter Palestinian action is what we do all the time and what we will continue to do.” Now, that was a year ago. Now things are different, Senator Mitchell. Can you talk about why the U.S. was previously blocking resolutions such as simply criticizing the expansion of Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories?

GEORGE MITCHELL: It has been, for many decades, under presidents of both parties, U.S. policy that the differences between Israelis and Palestinians should be resolved in direct negotiations between the parties, with the support and assistance of the United States and other allies. And as a necessary corollary to that, U.S. policy has been that the issues should not be resolved outside of direct negotiations. And so, unilateral action by either side to bring about a change that would alter the circumstances on the ground, or that would resolve an issue unilaterally that should be resolved in negotiations, were to be resisted. That is why the United States has consistently, publicly opposed Israel’s policies and actions regarding settlements, even as it has opposed publicly Palestinian efforts to resolve other issues outside of direct negotiations. So, American policy has been clearly consistent.

What is different now, of course, is that is all premised on the basis that there will be a direct negotiation between Israelis and Palestinians to achieve the goals that each seeks—security for Israel and its people, and a state for the Palestinian people. The reason that circumstances have changed now is that Prime Minister Netanyahu, on the day before his election, said that there would not be a Palestinian state while he was prime minister. That, effectively, undermined the principle of American policy, of what our objectives would be. The next day, he appeared to walk back from that, and so there is now some question about policy in that regard, and I think that is what has led to the review that you described earlier.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to William Quandt, who served on the National Security Council under Presidents Carter and Nixon. At a recent event, he suggested the U.S. needs to impose a cost on Israel for maintaining the occupation.

WILLIAM QUANDT: What doesn’t work is just saying, “You know what needs to be done, but there are no consequences if you don’t do it.” And that’s what we’ve done in the past, you know. And we use language that, if I were to try to translate it, I wouldn’t know what to say. We say the illegitimacy of continued settlement activity, but we don’t say that the settlements are illegal.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s William Quandt, a former National Security Council official, saying the status quo simply doesn’t work. Your response to this, Senator George Mitchell? And also, if you could respond to the other controversial statement, to say the least, of what Netanyahu said on that day of the elections, concerned about the Arab vote that was turning out?

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, he has apologized for that, and so I think that’s a separate issue from the first one that you described.

The fact is, of course, that both sides have, for a very long time, urged that the United States impose consequences on the other side. Both regard that as the way to resolve the issue. Palestinians and many Arabs repeatedly told me in meetings that the way to get this issue solved is for the United States to cut off all aid to Israel. “They’re dependent on you,” they said, “and if you cut off all aid, they’ll do what you want.” The Israelis, on the other hand, make exactly the same statement regarding aid to Palestinians. “They’re dependent on you,” they told me, “and if you will just cut off all aid to the Palestinians, they’ll do what you want.”

In my judgment, neither of those options is viable or would work. Israel is a democracy, a vibrant democracy. They are a proud and sovereign people. And taking punitive action, I think, would be, first, inappropriate, because of our close relationship to them, and secondly, I think it would be counterproductive. I do not think it would produce the desired result. It would further isolate the relations—further separate the relations between the two parties and reduce American influence there. And I don’t think that’s helpful in what we want, is the objective of a peace agreement between Israel and Palestinians and, equally important, normalization of relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, most of whom are also allies with the United States and who, paradoxically and somewhat ironically, are aligned with Israel on the issue of Iran and nuclear weapons. There is no stronger supporter of the position that Prime Minister Netanyahu is taking on the Iran nuclear deal than the government of Saudi Arabia, for example, which disagrees with Israel on other issues. So, it’s complicated. It’s difficult.

There is a powerful temptation to resort to, “Well, if we just do this, they’ll do that, and if we take this action, they’ll take that action.” I don’t think that’s the case. I think, ultimately, there has to be a discussion between the parties, with the strong support of the United States to achieve the mutually beneficial objectives. Israel has a state. They don’t have security. They want it, and they deserve it. The Palestinians don’t have a state. They want one, and they deserve one. Israel is not going to get security until the Palestinians get a state, and the Palestinians are not going to get a state until the people of Israel have a reasonable and sustainable degree of security. It is in their mutually beneficial interest to reach agreement. And I think, over time, that’s going to become clear to the public on both sides, as well as important not to leave out of the discussion, following that, the normalization of relations between Israel and its neighbors, its Gulf Arab neighbors in the region, which would be beneficial to all concerned.

AARON MATÉ: But, Senator, if we’re talking about taking punitive measures, can we agree that the two parties are not equal? They’re not occupying each other. It’s Israel that’s been occupying the Palestinians for nearly 50 years. They have nuclear weapons. They’re a huge power. Even during the so-called peace process, the settlements have expanded massively. So, Palestinians can say, “Well, look, I mean, the status quo of 50 years simply has not worked. Israel, Israel’s largest—the U.S., Israel’s largest supporter, has to change its policy decisively.”

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, it is true that the parties are not equal, of course. And one reason for having outside participation in the process is to provide an independent interlocutor, someone who would assist the parties in reaching agreement. And despite the criticism of the United States by many, there is in fact no other entity in the world that can perform that task other than the United States government. No other entity can create the circumstances, the conditions, the follow-up that is necessary for these agreements. And so, we do have an important role to play. We can play it.

We are, and will continue to be, close friends, allies and supporters of the people of Israel. That doesn’t mean that we agree with the government of Israel on every issue, and surely, the disagreements between the United States and Israel in recent weeks have been very well documented and displayed for all the world to see. At the same time, we support a Palestinian state. President George W. Bush set that out very persuasively and comprehensively in several speeches, including one he made in Jerusalem in January of 2009.

So, I think that the United States can and must play a central role in bringing about an agreement and, most importantly, seeing that an agreement is adhered to over time. And I think that’s the role we’re going to play. I think they will come around to it on both sides. I don’t think that we should say it is somehow our role to take punitive action against Israel so as to try to equal the status between them and the Palestinians. That wouldn’t work, and I don’t think it would achieve the desired objective.

AMY GOODMAN: Ahead of a trip to Israel this week, House Speaker John Boehner called President Obama’s recent criticism of Netanyahu reprehensible. Speaking to CNN, the House speaker also suggested it’s the fault of the Obama administration that Netanyahu has rejected Palestinian statehood.

SPEAKER JOHN BOEHNER: I think the animosity exhibited by our administration toward the prime minister of Israel is reprehensible. And I think that the pressure that they’ve put on him over the last four or five years has, frankly, pushed him to the point where he had to speak up. I don’t blame him at all for speaking up.

AMY GOODMAN: I’d like you to respond to the House speaker, the Republican leadership siding with Netanyahu, a foreign prime minister, over President Obama.

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, I don’t agree with Speaker Boehner on either of the points that he made. Of course, there’s a long history in the United States, which is an open, vibrant democracy, of people disagreeing with the president. That’s what is essential to democracy, that the absence of support for government policies at any given time is not evidence of a lack of patriotism. It’s essential to our free system. On the particular issues that Speaker Boehner has just described, while I fully respect his right to express his view, I respectfully, but strongly, disagree with the conclusions that he reached, that somehow it’s President Obama’s fault that Prime Minister Netanyahu has made differing statements with respect to a Palestinian state.

AARON MATÉ: And, Senator, should peace talks ever resume, what do you see as the major sticking points that might prove to be an obstacle to talks? And do you have any ideas for what solutions could be introduced?

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, all of the issues are sticking points. There are no easy issues in the Palestinian-Israeli dispute. They’re all important—where the borders would be; the distribution and rights with respect to water, which is a crucial issue in that region of the world, and, of course, in other parts of the world; the status of the right of return of Palestinians; the issue of Jerusalem, whether it should be the capital of both countries or not. And so, you have a whole range of very, very difficult issues, but, in my judgment, all of which can be resolved if there is a basis of trust between the two parties.

This discussion has been long and complicated, but it hasn’t mentioned what, in my judgment, is the single most important issue, and it is the high level of mistrust between both societies and both leaders. Having had long experience in the region, having met many, many times with Prime Minister Netanyahu and his predecessors, and President Abbas and his predecessor, I think that’s the single most difficult issue. Prime Minister Netanyahu, in my opinion, does not believe that President Abbas has either the will or the capacity, personal or political strength, to reach agreement and push one through to approval and implementation. President Abbas, on the other hand, does not believe that Prime Minister Netanyahu is serious about getting an agreement.

When Prime Minister Netanyahu announced in June of 2009 that he favored a two-state solution, no Palestinians believed that he was telling the truth, and neither did any other Arabs. They thought he was saying that just to accommodate the pressure from the United States. As Speaker Boehner has suggested, this is really the reverse side of that argument. And so, when Prime Minister Netanyahu, on the day before the recent election, said that there wouldn’t be a state, all of the Arabs reacted with “I told you so. We didn’t believe him in the first place.” And then, of course, when he appeared to walk back from that on the following day, that just furthered the impression of mistrust on the part of the Palestinians and the Arabs.

So, at the root cause of this is that you have two leaders who do not believe that the other has the intent, sincerity or capability to reach an agreement, and are therefore reluctant to take any steps that would impose a political cost on them within their societies, because both societies are divided. Prime Minister Netanyahu just got elected, so he represents the democratic result of a free and open election in Israel and the strong sentiment among his party and his supporters not there ever to be—for there not ever to be a Palestinian state on the West Bank. On the other hand, there are many Israelis who favor a two-state solution. On the Palestinian side, it’s about 50-50. You have Fatah, the principal party of the Palestinian Authority, headed by the President Abbas, who favor a two-state solution and who favor peaceful, nonviolent negotiation to get there. On the other hand, Hamas, about half, and centered primarily in Gaza, who are opposed to an Israeli state, who are opposed to—who want to retain the right to use violence to end the occupation, as they say. And so, both sides are divided. And if any leader takes a—makes a concession, he gets domestic political criticism. Well, if you don’t think there’s ever going to be an agreement because the other guy is not sincere, you’re not willing to take steps to move in that direction. That’s at the core of this problem, and I think that’s what has to be overcome.

AARON MATÉ: But, Senator, on the issue of Hamas, first of all, they were elected in 2006, so they are a legitimate government in Gaza, whether or not the U.S. and Israel like them or not, but Israel won’t deal with them. But also, on the issue of even Israeli and Palestinian statehood, hasn’t Hamas basically tacitly accepted Israel’s right to exist within its '67 borders, because Hamas has said, “We would accept a Palestinian state in the Occupied Territories.” In doing so, you're basically saying that “we recognize Israel, even if we don’t directly do it.”

GEORGE MITCHELL: Well, first off, they won a parliamentary election. Their government is divided into an executive and a parliament. They didn’t win the presidency. What was at stake was the parliamentary election. President Abbas remained the democratically elected leader of the country. They then, in a violent uprising, defeated the forces of President Abbas and Fatah, and evicted them from Gaza and seized both executive and parliamentary control in Gaza. So let’s be clear about that. They didn’t win control of Gaza in an election. They won control of Gaza in a military action, which expelled the forces of the Palestinian Authority.

Secondly, Hamas has prevented any election from occurring since then. They have the interesting political approach of they criticize Abbas as being illegitimate because he hasn’t been re-elected since his term expired. The reason he hasn’t been re-elected is that they won’t permit an election to occur in Gaza. And there are questions about whether an election could occur in Jerusalem, as well.

So, secondly, on the issue of the Hamas and Israel, you say “tacitly.” Well, if you were an Israeli, someone says, “Well, look, I’ll do this tacitly, but I won’t do it explicitly,” you’d be suspicious. And the Israelis rightly are, that they say, not—Hamas doesn’t say, “We tacitly recognize Israel.” Other people say it, as you have said it. Hamas says, “We’re against Israel.” So, I think you have to be very careful about implying a belief in someone who states the opposite, and rather, I think, you should rely on their actions. And so, I have always felt that if we could get a real talk going between the Palestinian Authority and the Israelis, that had a serious basis for proceeding, that’s the best way to draw Hamas in and get them to reverse their positions that now represent the impediment to their participation.

Media Options