Related

President Obama spoke on Saturday in Selma, Alabama, near the Edmund Pettus Bridge where civil rights activists led three marches 50 years ago to demand equal voting rights. “The idea of a just America and a fair America, an inclusive America, and a generous America — that idea ultimately triumphed,” Obama said. “Because of what they did, the doors of opportunity swung open not just for black folks, but for every American. Women marched through those doors. Latinos marched through those doors. Asian Americans, gay Americans, Americans with disabilities — they all came through those doors.” He concluded: “We know the march is not yet over. We know the race is not yet won.”

Transcript

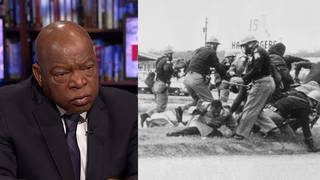

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: It is a rare honor in this life to follow one of your heroes. And John Lewis is one of my heroes. […]

As John noted, there are places and moments in America where this nation’s destiny has been decided. Many are sites of war—Concord and Lexington, Appomattox, Gettysburg. Others are sites that symbolize the daring of America’s character—Independence Hall and Seneca Falls, Kitty Hawk and Cape Canaveral. Selma is such a place.

In one afternoon 50 years ago, so much of our turbulent history—the stain of slavery and anguish of civil war, the yoke of segregation and tyranny of Jim Crow, the death of four little girls in Birmingham, and the dream of a Baptist preacher—all that history met on this bridge. It was not a clash of armies, but a clash of wills, a contest to determine the true meaning of America. And because of men and women like John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, Hosea Williams, Amelia Boynton, Diane Nash, Ralph Abernathy, C. T. Vivian, Andrew Young, Fred Shuttlesworth, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., so many more, the idea of a just America and a fair America, an inclusive America and a generous America, that idea ultimately triumphed. […]

Because of campaigns like this, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Political and economic and social barriers came down. And the change these men and women wrought is visible here today in the presence of African Americans who run boardrooms, who sit on the bench, who serve in elected office, from small towns to big cities, from the Congressional Black Caucus all the way to the Oval Office.

Because of what they did, the doors of opportunity swung open not just for black folks, but for every American. Women marched through those doors. Latinos marched through those doors. Asian Americans, gay Americans, Americans with disabilities, they all came through those doors. Their endeavors gave the entire South the chance to rise again, not by reasserting the past, but by transcending the past. What a glorious thing, Dr. King might say. And what a solemn debt we owe.

Which leads us to ask: Just how might we repay that debt? First and foremost, we have to recognize that one day’s commemoration, no matter how special, is not enough. If Selma taught us anything, it’s that our work is never done. The American experiment in self-government gives work and purpose to each generation. Selma teaches us, as well, that action requires that we shed our cynicism, for when it comes to the pursuit of justice, we can afford neither complacency nor despair.

You know, just this week, I was asked whether I thought the Department of Justice’s Ferguson report shows that, with respect to race, little has changed in this country. And I understood the question. The report’s narrative was sadly familiar. It evoked the kind of abuse and disregard for citizens that spawned the civil rights movement. But I rejected the notion that nothing’s changed. What happened in Ferguson may not be unique, but it’s no longer endemic, it’s no longer sanctioned by law or by custom. And before the civil rights movement, it most surely was.

We do a disservice to the cause of justice by intimating that bias and discrimination are immutable, that racial division is inherent in America. If you think nothing’s changed in the past 50 years, ask somebody who lived through the Selma or Chicago or Los Angeles of the 1950s. Ask the female CEO, who once might have been assigned to the secretarial pool, if nothing’s changed. Ask your gay friend if it’s easier to be out and proud in America now than it was 30 years ago. To deny this progress, this hard-won progress, our progress, would be to rob us of our own agency, our own capacity, our responsibility to do what we can to make America better.

Of course, a more common mistake is to suggest that Ferguson is an isolated incident, that racism is banished, that the work that drew men and women to Selma is now complete, and that whatever racial tensions remain are a consequence of those seeking to play the race card for their own purposes. We don’t need a Ferguson report to know that’s not true. We just need to open our eyes and our ears and our hearts to know that this nation’s racial history still casts its long shadow upon us. We know the march is not yet over. We know the race is not yet won. We know that reaching that blessed destination, where we are judged, all of us, by the content of our character, requires admitting as much, facing up to the truth. “We are capable of bearing a great burden,” James Baldwin once wrote, “once we discover that the burden is reality and arrive where reality is.” […]

For everywhere in this country, there are first steps to be taken, there’s new ground to cover, there are more bridges to be crossed. And it is you, the young and fearless at heart, the most diverse and educated generation in our history, who the nation is waiting to follow. Because Selma shows us that America is not the project of any one person, because the single most powerful word in our democracy is the word “we”—we the people; we shall overcome; yes, we can. That word is owned by no one. It belongs to everyone. Oh, what a—what a glorious task we are given to continually try to improve this great nation of ours.

Fifty years from Bloody Sunday, our march is not yet finished. But we’re getting closer. Two hundred and thirty-nine years after this nation’s founding, our union is not yet perfect, but we are getting closer. Our job’s easier because somebody already got us through that first mile, somebody already got us over that bridge. When it feels the road’s too hard, when the torch we’ve been passed feels too heavy, we will remember these early travelers and draw strength from their example and hold firmly the words of the prophet Isaiah: “Those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on the wings like eagles. They will run and not grow weary. They will walk and not be faint.” We honor those who walked so we could run. We must run so our children soar. And we will not grow weary, for we believe in the power of an awesome God, and we believe in this country’s sacred promise. May he bless those warriors of justice no longer with us, and bless the United States of America. Thank you, everybody.

Media Options