Guests

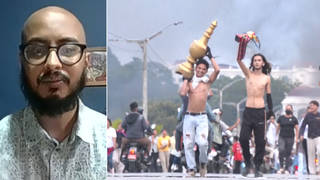

- Costas Panayotakisprofessor of sociology at the New York City College of Technology at CUNY and author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.

Tens of thousands of Greeks have protested against further austerity cuts ahead of a key referendum on a new European bailout. The demonstrations come as the country confirms it will not meet the deadline for a $1.8 billion loan repayment due by 6 p.m. Eastern time tonight, deepening Greece’s fiscal crisis and threatening its exit from the eurozone. Greece will hold a vote this Sunday on whether to accept an austerity package of budget cuts and tax hikes in exchange for new loans. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has urged a “no” vote, calling the proposal a surrender. We go to Greece to speak with Costas Panayotakis, professor of sociology at the New York City College of Technology at CUNY and author of “Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show in Greece, where tens of thousands of Greeks protested Monday against further austerity cuts. The demonstrations come as the country confirms it will not meet the deadline for a $1.8 billion loan repayment due by 6:00 p.m. Eastern time tonight.

NIKO: [translated] We have come here today because we want to tell the government and the whole of Europe that the government must not back down. Austerity is destroying people. And this must end. The Greek people have suffered a lot.

AMY GOODMAN: The European Commission wants Greece to accept an austerity package in exchange for new loans that would help it avoid a default. But Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has refused to accept the bailout deal, calling it a, quote, “humiliation.” Over the weekend, Tsipras announced a national referendum set for this Sunday on whether Greece should accept the terms of a new bailout. The European Central Bank followed by rejecting Greece’s request to extend an emergency loan program until after the vote. In response, Tsipras announced the closure of Greek banks and the stock market, as well as restrictions on bank transfers. During a nationally televised interview Monday night, Tsipras called the rejection of a loan extension “blackmail” and called for Greeks to vote no this Sunday.

PRIME MINISTER ALEXIS TSIPRAS: [translated] If the Greek people want to proceed with austerity measures in perpetuity, with austerity plans which will leave us unable to lift our heads, to have thousands of young people leaving for abroad, to have high unemployment rates and new programs and loans, if this is their choice, we will respect it, but we will not be the ones to carry it out. On the other hand, if we want to claim a new, dignified future for our country, then we will do that all together. People have power in their hands when they decide to use it.

AMY GOODMAN: Meanwhile, German Chancellor Angela Merkel played down prospects of a breakthrough with Greece in the coming days, but said she would restart talks after Sunday’s referendum.

CHANCELLOR ANGELA MERKEL: [translated] This generous offer was our contribution towards a compromise, so it must be said that the will for a compromise on the Greek side was not there. We made clear today that if the Greek government seeks more talks after the referendum, we will of course not say no to such negotiations.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, for more, we go directly to Greece, just outside Sparta, where we’re joined by Costas Panayotakis. He is a professor of sociology at the New York City College of Technology at CUNY and author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Costas. Can you just describe what’s happening right now in Greece?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, there are capital controls, and the ATMs were closed yesterday, so there is a limit to how much money Greeks can withdraw—60 euros. But tourists can withdraw from foreign accounts, can withdraw, you know, as much as they have in their accounts. Beyond that, politically speaking, there is lots of tension, but the situation, even though it’s an unprecedented situation, it was very orderly. And it was remarkable, actually, on a day when, you know, a government closed down the banks, that there was a massive rally in support of the government, because people are very simply tired and exhausted and angry with austerity measures that have devastated Greek society. So, this is, you know, in a nutshell, some of the things that have been going on in the last few hours.

AMY GOODMAN: So, people are allowed—Greeks are allowed to take out 60 euros from the bank. That’s what? Like 67 U.S. dollars. What has been the response in the streets? I mean, you have a lot of developments here, with the referendum being called for Sunday, mass protests taking place.

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: I lost the connection.

AMY GOODMAN: What has been the response in the streets, Costas?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, I think it’s a mixed response. On the one hand, of course, there is anxiety and people, you know, going to the ATMs and trying to get money, and some degree of frustration. But there is also some understanding that the previous policies were not working. So, it’s a mixed response. The same people oftentimes have contradictory feelings. And, of course, there is also a divide within Greek society, with some people being in support of the government and its decisive stand, and others are being more critical.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain exactly what the referendum puts to the people of Greece Sunday?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah. There are two documents with the proposals of the Europeans regarding what should have been the measures adopted by the Greek government in order to get the latest installment of the loan that it would need to keep servicing its debt in the coming months. And this has very heavy, very harsh measures. The idea that Chancellor Merkel, as in your clip, suggested that this was a generous offer would seem like a cruel joke to all Greeks, even opponents of the government. We are talking about, you know, reducing pensions even further. We are talking about escalation of sales taxes. We’re talking about undermining the livelihood of people who have seen their living standards already decrease dramatically in the last five years.

AMY GOODMAN: On Monday, the EU Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, accused the Greek government of betraying efforts to broker a deal.

JEAN-CLAUDE JUNCKER: [translated] This isn’t a game of liar’s poker. There isn’t one winner and another one who loses. Either we are all winners or we are all losers. I am deeply distressed, saddened by the spectacle that Europe gave last Saturday. In a single night, the European conscience has taken a heavy blow. Goodwill has somewhat evaporated.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker. Costas, can you respond?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, I think there is a contradiction in his speech. He starts, as in this clip, to try to seem like he’s above this dispute and claiming he wants to bring the two sides together, but then, a few minutes later into the same speech, he basically attacked the Greek government as basically lying to Greek people as to what the terms were, and that even as—even foreign journalists, from Financial Times and elsewhere, pointed out that he was the one who was lying when he claimed that there was not a proposal to cut Greek pensions. So, I mean, there is an element of hypocrisy there. And we also have to keep in mind that Juncker was the prime minister of Luxembourg, which has been a tax haven that has systematically undercut the finances of other European nations, that’s, you know, mightily contributed to the debt crisis that now he claims to want to resolve.

AMY GOODMAN: On Monday, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras responded to critics who say Greece could be pushed out of the eurozone.

PRIME MINISTER ALEXIS TSIPRAS: [translated] The economic cost if the eurozone is dismantled, the cost of a country in default, which to the European Central Bank alone owes more than 120 billion euros, is enormous, and this won’t happen, in my view. My personal view is that their plan is not to push Greece out of the eurozone; their plan is to end hope that there can be a different kind of policy in Europe.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Costas Panayotakis, respond.

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I think—I think Syriza was a little over-optimistic, to begin with, as to the possibility of reversing austerity within the eurozone, and this has created difficulties for them. But I think it’s probably true that Chancellor Merkel, especially, and other leaders would not want to be responsible for the rupture of the eurozone, both for economic reasons that the prime minister mentioned but also for geopolitical reasons.

AMY GOODMAN: So what does this mean for this experiment, for the whole Syriza movement that has arisen in Greece? What do you think is going to happen? And how would you evaluate the prime minister, Alexis Tsipras?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, for a long time, Syriza had been making significant concessions to the eurozone’s austerity agenda. I mean, the final offer that the Greek side made, you know, had made significant concessions when compared to the platform of the party. I mean, this is—we are talking about a country that has over 25 percent unemployment, and yet the Greek government was willing to basically propose budget surpluses. I mean, this is a policy—this is not wild leftist. This is a policy well to the right of Keynesian economics. But unfortunately in the eurozone today, there is no real democracy, because basically Keynesianism is bound out of court, and basically what would be a policy that would appeal to the far right of the Republican Party in the U.S. is the only economic policy that is allowed by the eurozone, even though this policy is basically destroying European societies. And Greece is a good example of that.

AMY GOODMAN: So, your book, Costas, is called Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy. What would you say is happening with Greece right now?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Yeah, I mean, my book was a critique of neoclassical economics, which is based on the concept of scarcity and argues that basically the free market is the best way to make effective use of scarce resources. And what we’ve seen, of course, with the Greek crisis is a precise refutation of this claim. An economy where 25 percent of the labor force cannot find a job, even though they need to, they want—they would love to work, obviously, it’s not going to—it’s not an efficient economy. An economy where, you know, the most educated young people have to leave the country, after the country invested in their education, and go somewhere else is clearly not an efficient economy. So, even though my book was not specifically on Greece—it did mention Greece, but it was not just on Greece—I think Greece is a good example of how mythical the neoliberal claim is that free markets lead to efficient use of scarce resources.

AMY GOODMAN: If you might look through the crystal ball for us, Costas, in this last minute we have, what do you think will happen on Sunday? And ultimately, what’s going to happen in Greece?

COSTAS PANAYOTAKIS: Well, the first question is whether the referendum will happen on Sunday. I think the European response clearly makes it clear that they want to sabotage the very possibility of a referendum. And, you know, the situation is very, very much in flux. Things have been very orderly, as I said, which is—it is good for the government, and it increases the likelihood of, you know, a “no” vote. But it would be, of course, unwise to try to make a prediction.

And I think one of the factors that will play a role is that if there is a “yes” vote to these measures, Prime Minister Tsipras has said that he would not continue being prime minister, so that would add to economic disruption the possibility of political instability, because then you might need to have new elections. And then you might have a situation where Syriza wins again, because that’s what recent polls have shown. So, I think people who are concerned about economic disruption, or even political instability, may actually find out that—may actually realize that even if they feel frustrated, you know, a “yes” vote would not necessarily solve the problem as they perceive it.

AMY GOODMAN: Costas Panayotakis, I want to thank you for being with us, author of Remaking Scarcity: From Capitalist Inefficiency to Economic Democracy, professor of sociology at New York City’s College of Technology at CUNY. This is Democracy Now! When we come back, another deadline looms. It’s in Iran. That’s where we’re going. Stay with us.

Media Options