Guests

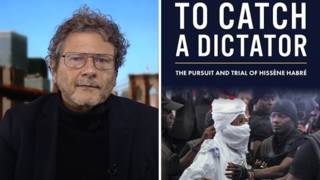

- Reed Brodycounsel and spokesperson for Human Rights Watch. He has worked with victims of Hissène Habré’s regime since 1999 and played a critical role in bringing Habré to trial.

The former U.S.-backed dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré, has been convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison. Habré is accused of killing as many as 40,000 people during his eight years in power in the 1980s. At the landmark trial in Senegal, Habré was convicted of rape, sexual slavery and ordering killings during his reign of terror. Habré was tried in a special African Union-backed court established after a two-decade-long campaign led by his victims. This is the first time the leader of one African country has been prosecuted in another African country’s domestic court system for human rights abuses. We go to Dakar, Senegal, to speak with Reed Brody, counsel and spokesperson for Human Rights Watch. He has worked with victims of Hissène Habré’s regime since 1999 and played a critical role in bringing Habré to trial.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In an historic ruling in Dakar, Senegal, the former dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré, has been convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison. The former U.S.-backed leader is accused of killing as many as 40,000 people during his eight years of reign in power in the '80s. At the landmark trial in Senegal, Habré was also convicted of rape, sexual slavery and ordering killings during his reign of terror. This is Judge Gustave Kam announcing the court's decision on Monday.

JUDGE GBERDAO GUSTAVE KAM: [translated] Hissène Habré, the court condemns you to life in prison. You have a period of 15 days from the pronouncement of this judgment to appeal the decision in accordance with the criminal procedure code.

AMY GOODMAN: Habré was tried in a special African Union-backed court established after a two-decade-long campaign led by his victims. This is the first time the leader of one African country has been prosecuted in another African country’s domestic court system for human rights abuses. After the verdict was read, survivors of Habré’s regime embraced each other in the courtroom. This is Souleymane Guengueng, founder of the Chadian Association of Victims.

SOULEYMANE GUENGUENG: [translated] Honestly, I’m very satisfied. I do not have the words, but let the name of God alone be glorified. It hurts me that many of my colleagues died along the way. They could not be here to see the result, which is why I was moved and brought to tears. But it is still a truly happy moment. I have to say it, but I cannot say it enough. Hissène Habré was sentenced to life imprisonment. He will finish off his life in prison, and that’s all we wanted. I hope this serves as a lesson to all the other dictators out there.

AMY GOODMAN: Hissène Habré is a former U.S. ally who’s been described as “Africa’s Pinochet.” He came to power with the help of the Reagan administration in 1982. The U.S. provided Habré with millions of dollars in annual military aid and trained his secret police, known as the DDS. After Habré’s sentencing, Human Rights Watch’s attorney Reed Brody tweeted, quote, “Habré’s conviction for these horrific crimes after 25 years is a huge victory for his Chadian victims, without whose tenacity this trial never would have happened. This verdict sends a powerful message that the days when tyrants could brutalize their people, pillage their treasury and escape abroad to a life of luxury are coming to an end. Today will be carved into history as the day that a band of unrelenting survivors brought their dictator to justice,” unquote.

Well, for more, we go directly to Dakar, Senegal, where we’re joined via Democracy Now! video stream by Reed Brody, counsel and spokesperson for Human Rights Watch. He’s worked with victims of Hissène Habré’s regime since 1999 and played a critical role in bringing Habré to trial.

Reed Brody, welcome to Democracy Now! Share your reaction to the verdict yesterday.

REED BRODY: Thank you, Amy. Well, it’s just an immense satisfaction. I mean, as the judge was reading the verdict and as we heard his—you know, the narrative that the victims have been weaving for 25 years, basically detailed by the judge, who found the allegations credible, and we could see—we could see the way the judge was heading. It was just this immense moment of satisfaction. And right after the verdict, you know, we were embracing, and there were a number of widows who had come from Chad specially for the occasion, who started ululating. And, you know, I have—you know, very few people thought that this day would ever come. One of them was Souleymane Guengueng, who you highlighted before. And just, I mean, last night with Souleymane until 1:00 in our hotel room, we were rewatching a TV reading of the verdict, and just hard to believe that, you know, this day has come, that these victims have finally achieved justice. It’s—

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Reed, actually, talk about Souleymane Guengueng, who we just saw responding to the verdict. Tell us his story. I want to go back to 2008, when we spoke to this Chadian activist, who spearheaded the case. He described why it was so important to him for Habré to be tried. We’re going to go to that clip in just a minute. But tell us about what happened to Souleymane.

REED BRODY: So, Souleymane was a deeply religious civil servant. You know, he was thrown in jail on false charges. As people were dying around him in his prison cell, you know, he took an oath before God that if he ever got out, he would fight for justice. And when the prison—when Idriss Déby overthrew Hissène Habré and the prison doors swung open, Souleymane got together others and founded the first victims’ association, and has been fighting since then. Many of Habré’s accomplices were still and are still in Chad—mayors, police chiefs, governors. And they started making death threats against Souleymane and forced him to go into exile in the United States. And Souleyman’s been fighting for the last 10 years. I mean, when you aired that in 2008, Amy, we had already been working together for nine years. That was seven years—no, eight years ago.

AMY GOODMAN: I’ve got that clip of Souleymane Guengueng right now from 2008.

SOULEYMANE GUENGUENG: [translated] For everyone who has lived this kind of situation, they need to know that as long as Hissène Habré is not brought to justice, psychologically, morally, we are not healed, and that remains in our heads. The example is, when we were in Dakar eight years ago with Reed to file the case, and when Hissène Habré was indicted for the first time, it’s as if—those of us who were there, as if something came into our heads, and we were liberated from these things that were in our head. We, the victims, only really us, the victims, who understand how we need justice in order to be restored to our full strength and height; somebody who hasn’t survived this kind of torture can’t really understand that.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Chadian activist Souleymane Guengueng back in 2008. Reed Brody, take it from there.

REED BRODY: You know, this—Habré was arrested for the first time 16 years ago here in Senegal. And the previous government of Senegal just for 12 years gave us the runaround. I mean, Habré left—before Habré left Chad, he emptied out his country’s treasury, and he brought all that money here to Senegal and created a web of political influence and support. He also, I think, silently had the support of a lot of other African heads of state, who made it clear they didn’t want to see this precedent created. And so, the victims fought in Senegal. When the case was thrown out in Senegal, they went to Belgium. Belgium investigated the case for four years, requested Habré’s extradition. Senegal said no. We actually made an ally of the African Union, which said to Senegal, “Well, if you don’t want to extradite him to Belgium, you should prosecute him in Senegal.” President Wade, then, of Senegal agreed, but he didn’t do it.

And actually, Belgium took this case to the International Court of Justice, the World Court in The Hague. And in 2012, the World Court ruled by a unanimous decision that Senegal had a legal obligation to prosecute or to extradite Hissène Habré. And that same—in those same months, Macky Sall became the president of Senegal, and Macky Sall was one of the many leaders of Senegal who the victims had been visiting over the years, creating the political support here in Senegal, creating the political conditions. And since 2012, the government of Senegal has been behind this court, and as you said, it was a court established by Senegal and the African Union. The trial started last year, and yesterday we got the verdict.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to talk about the U.S. role, going back to President Ronald Reagan in 1982, with the rise of the Chadian dictator, Hissène Habré, but we’re going to break first. We’re talking to Reed Brody, counsel and spokesperson for Human Rights Watch, who has been working with victims of Hissène Habré’s regime since 1999 and played a critical role in bringing Habré to trial. We’re speaking to him in Dakar, Senegal, where Habré was tried and convicted. Stay with us.

Media Options