Guests

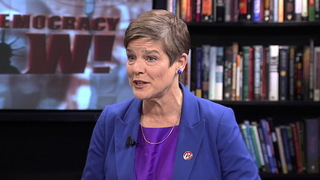

- Rebecca Petersinternational arms control advocate and part of the International Network on Small Arms. She led the campaign to reform Australia’s gun laws after the Port Arthur massacre.

In the wake of the shooting massacre that killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, the Senate is expected to vote today on four gun control measures. None of them would reinstate an assault weapons ban. The vote comes after Democratic Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy staged a filibuster for nearly 15 hours last week to demand action on gun control. We look at how Australia fought to change its culture of gun violence and won. In April of 1996, a gunman opened fire on tourists in Port Arthur, Tasmania, killing 35 people and wounding 23 more. Just 12 days after the attack, Australia’s conservative government responded by announcing a bipartisan deal to enact gun control measures. Since the laws were passed—now 20 years ago—there has not been another mass shooting in Australia. Overall gun violence has decreased by 50 percent. We are joined by Rebecca Peters, an international arms control advocate.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The Senate is expected to vote today on four gun control measures. None of the bills would reinstate an assault weapons ban. The vote comes after Democratic Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy staged a filibuster for nearly 15 hours last week to demand action on gun control after the Orlando massacre.

We turn now to look at how Australia fought to change its culture of gun violence and won. In April of 1996—20 years ago—a gunman opened fire on tourists in Port Arthur, Tasmania, killing 35 people, wounding 23 others. Just 12 days after the attack, Australia’s conservative government responded by announcing a bipartisan deal to enact gun control measures. Since the laws were passed, there has not been another mass shooting in Australia. Overall gun violence has decreased by 50 percent.

Last week, I spoke to Rebecca Peters, an international arms control advocate. I asked her about the campaign she helped lead to reform Australia’s gun laws after the massacre.

REBECCA PETERS: We had had, in those days, a series of massacres. We had a massacre about once a year. And each time, it was—there was an outcry, there was a lot of grief and anger and discussion about what should happen and pressure on the politicians. But each time, the politicians had said, “Well, this shouldn’t be”—everyone agreed it shouldn’t be a party political issue, but neither of the major parties was prepared to move first. And so, I suppose that the thing that happened was that the electoral—the electoral makeup of the government favored us at the time. We had just had a new government elected. It was a conservative government. And in a sense, it’s easier for a conservative government to change the gun laws, because they are more—the conservative party was seen more as the natural ally of the gun lobby. But really, you know, people die the same, whatever party they vote for. And so, that—but we thought it was particularly courageous of the conservative prime minister to say, “I’m going to deal with this once and for all.”

AMY GOODMAN: And explain, over the two weeks and then the year, what exactly the rules were that got passed for the people of Australia, and this massively dramatic—well, I mean, no more massacres in Australia.

REBECCA PETERS: Yeah. So, one of the important—so, the principal change was that—the ban on semiautomatic weapons, rifles and shotguns, assault weapons. And that was accompanied by a huge buyback. And in the initial buyback of those weapons, almost 700,000 guns were collected and destroyed. There were several further iterations over the years, and now almost a million—over a million guns have been collected and destroyed in Australia. And the—but also, the thing is that sometimes countries will make a little tweak in their laws, but if you don’t, you have to take a comprehensive approach. It doesn’t—if you just ban one type of weapon or if you just ban one category of person, if you don’t do something about the overall supply, then basically it’s very unlikely that your gun laws will succeed. So this was a comprehensive reform related to the importation, the sale, the possession, the conditions in which people could have guns, storage, all that kind of thing that can—the situations in which guns could be withdrawn.

Often there’s not much thought given to, OK—often the focus is on how people can buy guns, but not much thought is given to in what circumstances those guns should be removed. For example, obviously, if someone doesn’t qualify to own a gun, then—if they qualify at the beginning, but if then they do something which makes them unqualified, they should lose their license and their guns. And that is an important part of Australia’s gun laws, as well. Someone who commits domestic violence, for example, who has a gun legally, will lose that gun and the license to have the gun.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is a critical point, because the ex-wife of Omar Mateen said that he beat her, said he had an obsession with guns. She was not talking about him as a Muslim extremist. She was talking about him as a wife abuser, as a man who was mentally ill, as a man who was obsessed with guns and wanting to be a cop.

REBECCA PETERS: Exactly. And particularly domestic violence is one of those things that usually doesn’t turn up in a criminal record, because, as we know, most domestic violence doesn’t result in a criminal conviction. In fact, most domestic violence doesn’t involve a legal process at all. But local police and family members know about domestic violence. And so, a crucial part of the new laws is proper checking of the background of people who are applying to have guns. So, in relation—and it’s not only domestic violence, it’s also depression and alcohol abuse, and many other factors can make a person at risk of violence, not to mention people who have—who are vehemently racist or resentful. I guess the thing is that what we all—what those of us in other countries think every time we see one of these tragedies in America, we have people all around the world who are full of unhappiness, of hatred, of resentment, whatever, but it seems to—but in other countries, those people don’t have easy access to weapons designed to kill lots of people.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to a clip of President Obama speaking last week about the nation’s gun laws.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: I just came from a meeting today in the Situation Room in which I’ve got people who we know have been on ISIL websites, living here in the United States, U.S. citizens, and we’re allowed to put them on the no-fly list when it comes to airlines, but because of the National Rifle Association, I cannot prohibit those people from buying a gun. This is somebody who is a known ISIL sympathizer. And if he wants to walk into a gun store or a gun show right now and buy as much—as many weapons and ammo as he can, nothing’s prohibiting him from doing that, even though the FBI knows who that person is.

AMY GOODMAN: So that is President Obama speaking June 2nd. It’s not after this massacre that took place at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. That was just June 2nd. Respond to what the president has said.

REBECCA PETERS: Well, that’s absolutely right. And that’s the approach that other countries take, that you can recognize that—I mean, in Australia, we still have hunting, we still have target shooting. People still own guns in Australia. It’s just that they don’t own assault weapons, and they don’t—and they have to qualify—they have to proceed through a much—a more stringent process to qualify.

AMY GOODMAN: Was there any campaign that was launched, like you’re a wimp if you need a semiautomatic weapon to take down an animal?

REBECCA PETERS: In fact, absolutely, we had some—we had some interesting allies that emerged during the—during the discussion after Port Arthur. One was that Australia’s Olympic shooters, who had done very well in the Atlanta Olympics, they handed in their semiautomatics, and they said, “We support the new gun laws.” The other thing was, there’s an organization of professional shooters in Australia, who were the—they’re like the original Crocodile Dundee. They’re these super-macho guys who were employed to clear out feral animals from the national parks. And they said, “If you need a semiautomatic weapon to kill an animal, then you’re a city boy who shouldn’t be out here with a gun in the first place.” So, and we know also—we knew in Australia, as, in fact, in the U.S., the opinion polls and the surveys of gun owners showed that most gun owners supported commonsense gun laws, reasonable restrictions. But the gun—it was the gun lobby that was—that always took this very extreme position that opposed absolutely any change. And that is similar in the U.S. It’s just that in Australia, that gun lobby didn’t get its way.

AMY GOODMAN: Rebecca Peters, you’re in New York because of a U.N. conference that just took place on gun control. Can you talk about what happened? And what was the role of the U.S. in it?

REBECCA PETERS: Yes. So, we just had the U.N. conference on small arms, that occurs every couple of years here at the United Nations. All countries of the world come together to talk about what to do about guns, gun trafficking, gun violence and the—and to try to move toward some kind of consensus so that countries can work together, because guns travel across borders internationally, just as they travel across state borders within the U.S. So, at this conference, there’s a—it’s an attempt to try to advance the process of cooperating between countries.

Unfortunately, at the U.S.—at this conference, the U.S. being the largest manufacturer and the largest exporter of guns in the world, the U.S. took a position that was limiting on the progress that could be made. So, for example, one of the topics up for discussion was: Should ammunition be regulated? Everyone in the U.N. agrees that guns should be regulated, but what about ammunition, since we know that ammunition is what makes guns so deadly? And, in fact, someone who has a gun illegally and undetected depends on being able to get ammunition without regulation in order to be able to commit crimes. So most countries of the world, overwhelmingly the majority of countries, want to regulate ammunition, as well. Unfortunately, the U.S., along with countries like Egypt, Iran, were—they took the position that ammunition should not be regulated. They did not—

AMY GOODMAN: The United States.

REBECCA PETERS: The United States.

AMY GOODMAN: The Obama administration.

REBECCA PETERS: Well, the United States delegation at the U.N. conference was one of the countries that was opposing the inclusion of ammunition in the final agreement. So—

AMY GOODMAN: On what grounds?

REBECCA PETERS: Well, it seems to be on the basis that it would restrict the liberty of American citizens to buy ammunition. I think—

AMY GOODMAN: And what is your response to that?

REBECCA PETERS: My response is that people who don’t have—that failing to restrict ammunition makes ammunition available for criminals. And there’s absolutely no reason why, if—I mean, you have gun control laws in the U.S. They’re not very strict in many places. But obviously ammunition should be regulated, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: So you’re saying the U.S. joined Egypt and Iran in trying to stymie world regulation around guns?

REBECCA PETERS: Well, what they tried to do was to reduce the strength of the agreement. So, various measures which most countries in the world wanted to have in order to have a strong agreement at the end of—and to provide a mandate for countries to do a lot more against the problem of guns, these countries, more conservative countries, like the U.S., Egypt and Iran, were against that.

AMY GOODMAN: We talked about Australia and the United States. Can you give us examples of other countries?

REBECCA PETERS: Sure. I mean, for example, in—the best comparison for the U.S. to make is with other developed countries, so other countries where the rule of law is in place and where police forces work reasonably well. There’s no point in comparing the U.S. with developing countries or countries that are in conflict or things like that. But say in Canada, in Germany, in France, in—you know, in European countries, and Australia, that the—all of those countries have a similar approach, which is you apply proper screening for people who want to have guns. You don’t permit people to have any gun they want. You do—you put some kind of limit on the arsenals that can be built up. And you take into account the knowledge of the people who are best able to tell you whether some—whether there’s anything of concern about a person. So, in those countries, the police are able to use their faculties to inquire, rather than just looking on a computer to see if someone has criminal convictions.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me toss to what the Republican presumptive nominee for president, Donald Trump, said today on CNN.

DONALD TRUMP: If you had some guns in that club the night that this took place, if you had guns on the other side, you wouldn’t have had the tragedy that you had. If people in that room—

ALISYN CAMEROTA: But there was.

DONALD TRUMP: had guns, with the bullets flying in the opposite direction right at him—

ALISYN CAMEROTA: I mean, but, Mr. Trump, there was an armed—there was an armed security guard.

DONALD TRUMP: —right at his head, you wouldn’t have had the same tragedy that you ended up having. And nobody even knows how bad that tragedy is, because I think probably the numbers will get bigger and bigger and worse and worse.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Donald Trump. Your response, Rebecca Peters?

REBECCA PETERS: I mean, to have a crowded, dark place with a lot of noise and a lot of people moving around, to have more than—to have had another person shooting in that place, or many more people shooting in that place, that would have increased the danger. The idea that the answer to the problem of too many guns is an even larger number of guns makes absolutely no sense at all.

AMY GOODMAN: Where does the U.S. stand when it comes to gun massacres in the industrialized world?

REBECCA PETERS: Well, the U.S. has the highest rate of gun deaths in the industrialized world. And in terms of—so, for example, the rates of gun deaths in the U.S. are about 11 times higher than in Australia and up to 15, 20 times higher than in some other developed countries. But in terms of massacres, the U.S. has a larger number of massacres even than countries in the developing world or countries in conflict. The number of mass shootings that occur in the U.S. outstrips any other country in the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Rebecca Peters helped lead a campaign 20 years ago to reform Australia’s gun laws after the Port Arthur massacre that killed 35 people. Australia hasn’t had a mass shooting in the past 20 years. Rebecca Peters is part of the International Network on Small Arms. She was in New York last week for a major U.N. conference on guns. And that does it for our show. If you want to see Part 1 of that interview, go to democracynow.org.

Also, Democracy Now! has several job openings, including news producer and senior TV producer, open immediately. Go to democracynow.org for more information.

Media Options