Guests

- Khalil Gibran Muhammadprofessor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.

A Minnesota jury’s conviction of former police officer Derek Chauvin on three counts for murdering George Floyd does not go far enough in dismantling police brutality and state-sanctioned violence, says historian and author Khalil Gibran Muhammad. “We know that while the prosecution was performing in such a way to make the case that Derek Chauvin was a rogue actor, the truth is that policing should have been on trial in that case,” Muhammad says. “We don’t have a mechanism in our current system of laws in the way that we treat individual offenses to have that accountability and justice delivered.” Muhammad also lays out the racist history of slave patrols that led to U.S. police departments, which he details his book, “The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

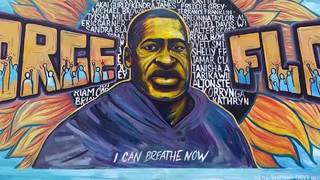

Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. Three weeks after the start of the trial, that was watched around the world, and after 10 hours of deliberation, a jury of 12 Hennepin County residents delivered their guilty verdicts Tuesday on all three counts against former police officer Derek Chauvin, who murdered George Floyd last May by kneeling on his back for nine-and-a-half minutes.

As we continue to discuss the verdict and its implications, we’re joined by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, author of The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America.

Professor Muhammad, welcome back to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Take us on a journey back. Respond to the verdict, but then talk about the beginning of policing in America and its connection to slave patrols.

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Good morning, Amy. And good morning, Juan.

I think that this verdict — I’ve been thinking a lot about how to respect the family’s sense of closure and what they deserve in the delivery of accountability in this case. But I’ve also been thinking about this in term — battle, in a broader context of a war, and that war being justice for Black people and for BIPOC people and for poor people in this country. And in this sense, the outcome of this trial represents a battle that was won, a long-fought and, as Kandace Montgomery so eloquently described in the work that she’s been doing, the consequence of years of organizing work in Minneapolis. And just to remind you, each one of these battles will take place in the courts of our country, whether it will be in Toledo, Ohio — I’m sorry, whether it will be in Chicago, whether it will be in this case, most recently, with Ma’Khia Bryant in Columbus, Ohio. And so, that’s how I think about the trial and the work that remains.

But, of course, we know that while the prosecution was performing in such a way to make the case that Derek Chauvin was a rogue actor, the truth is that policing should have been on trial in that case. And we don’t have a mechanism in our current system of laws in the way that we treat individual offenses to have that accountability and justice delivered. And the reason being, of course, is that our policing system was never really built to deal with individuals. It was built to control groups, and those groups ranging from Indigenous people during the period of colonization and the early 19th century, and, of course, for the vast majority of people of African descent in this country, for 250 years, in the context of chattel slavery, was meant simply to protect an economic system where people had been defined as property, and if that property decided to steal itself, there would be deputized, armed white men of every class and category in the society to ensure that they would not escape.

And that history has never left us. That history is still with us. And policing, right through this very moment, remains overwhelmingly concentrated within the most divested, poorest communities in our country, that are of color, because, truth be told, for rural white Americans who experience severe poverty, policing per capita is much lower. So, we have a system that began in the context of slavery and control, and remains, in its deepest roots, that same system.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Khalil, I wanted to ask you about that, because I often tell my students in journalism to go back into the archival history of our newspapers to see this represented vividly. For instance, in 1706, The Boston News-Letter, the first continuously published newspaper in America, wrote Blacks are, quote, “much addicted to Stealing, Lying, and Purloining.” And a few years later, its competitor paper — this is an amazing statement in a newspaper — said, quote, “The great Disorders committed by Negroes, who are permitted by their imprudent Masters … to be out late at Night … has determined several sober and substantial Housekeepers to walk about the Town in the sore part of the Night.” So, citizen watch patrols were already being developed in early 1700s to control the Black population of Boston. Of course, this, as you’ve so eloquently expressed, then becomes the actual — the slave patrols and then our modern police departments. To what degree are most Americans aware of this history?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Well, I think it’s fair to say most are not aware. Maybe the learning curve has steepened a bit over the past year, but the truth is, Americans, whether we talk about the origins of policing or the simple reality of the 350 years covering chattel slavery to the segregation period, we know empirically that most Americans are not taught these histories. This is true for African American children, as well, whose curriculum are covered by state legislatures, which are dominated by whites who are not willing to come to terms or reckon with this history.

And, Juan, I want to say one more thing about those examples that you described. What I think is so powerful about turning to colonial and antebellum archival records is that white people did not mince their words. They were quite clear and articulate about what it is that they were doing when they simply criminalized Blackness or they simply criminalized the right to be, as my colleague Kelly Lytle Hernández has written. And our language has become a way of obfuscating those same mechanisms. We live in a time, in this modern period of social media, where we have accelerated the capacity to say one thing in public but to do something else quite differently in our policy and practice. And so, those history lessons are critical — indeed, I would say, life-saving — when it comes to making sure that as we move forward from this moment, if it is even possible, that we come to terms with the clarity with which past political elites talked about what they were doing.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, in that vein, you mentioned that initially there were attempts to control and, obviously, suppress the Native populations. But especially in the light of the recent shooting of Adam Toledo, this history of the Latinos and other people of color — for instance, there was one book, Gunpowder Justice, that claims that the Texas Rangers, just between 1915 and 1920, killed 5,000 Mexicans in the state of Texas as a suppression force. And the L.A. Times recently reported that there have been 465 Latinos killed by police just in Los Angeles County since 2000. That works out to about one Latino every two weeks for the last 20 years have been killed just in L.A. County. This whole issue of policing being used as a means of suppression and terrorism of these communities?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Yeah, no, those reminders that anti-Blackness may have been the motivation for the infrastructure of policing, but it didn’t stop there. And I think that is part of the broader historical context in which we need to come to terms with the past as a predicate for the action and the work that has remained. I mean, Kandace Montgomery is such an articulate spokesperson for the work that’s happening on the ground, but she is exceptional. And the work of the Black Visions Collective is exceptional. The work of the Anti Police-Terror Project, led by James Burch in Oakland, is exceptional. We still have members of Black and Brown communities that are still in need of recognizing the broader limits of police reforming themselves.

And when you, Juan, describe the sheer toll that is happening within Latinx communities, and tethering that to the fact that we have evidence that it may be that there were just as many people of Central American or Mexican ancestry killed by lynch mobs or by police agencies, like the Texas Rangers, that number may exceed or match the numbers of recorded lynchings of African Americans in this country, is just astounding and only shows exponentially how much terror has been an instrument of control in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: [inaudible] Professor Muhammad, you’ve got The Guardian reporting on, in a data breach, police helping to fund Kyle Rittenhouse, the young man who opened fire and killed two Black Lives Matter activists and walked away, even as people were saying, “This is the guy that shot those protesters.” And you’ve got the police acting as terrorists themselves, the whole issue of violence directed against — and you write about this eloquently — against the poor. And also, if you can talk about new immigrants and how police are used?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Thank you, Amy. Listen, the fact of how much policing is baked into every system of our society, you know, when we think about what’s been happening at the border during the Trump administration, this is another expression of the way that the Trump administration simply weaponized the systems that were already in place, did not invent them.

And the degree to which something like the Kyle Rittenhouse example of a white man self-deputized as an anti-Black terrorist to shoot people, with the protections of the so-called Second Amendment, and then to be applauded and supported, to be given water on the scene, to later receive something like $600,000 in defense funds, many of which came from law enforcement itself, or to reflect on the fact that Donald Trump received 74 million votes in this election in calling for more policing, more white nationalism, more border control, more terrorism, and that the Republican Party, as we know now, is holding up the George Floyd Policing Act as a singular unit of support for this kind of ongoing terror that’s happening in this country, is just remarkable.

I mean, we are nowhere nears able at this time to recognize some consensus on a common way forward to recognize the humanity of people, whether they are asylum seekers coming into this country from Central America or whether they were born here in any part of this country. And as much as I am hopeful for the possibilities of the activist work of people like Kandace Montgomery, I think we all need to be as vigilant as possible that we are nowhere near where we need to be in order to expect that Black lives will not continue to be cut short by everything we’ve seen so far.

AMY GOODMAN: And just to say, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which was passed by the House but is being held up in the Senate, among its components, ban chokeholds, ban no-knock warrants, create a duty to intervene, create a public registry, overhaul qualified immunity. And Minneapolis Congresswoman Ilhan Omar tweeted after the verdict, “This is but a minuscule step on the path to justice. Next stops: Independent agency to investigate police misuse of force; Criminalize violence against protesters; Demilitarize police departments; Disband and deconstruct failed police departments.” Your response?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Well, I think that all — listen, I think that everything that Ilhan Omar has described is on the table. And I agree with her that the Justice Floyd Act, it limits the — well, demonstrates the limits of the federal government to control 18,000 decentralized agencies. And while, as she rightly notes, it is a first step — and I think it’s a good first step for that reason — much of this work will depend upon state legislatures to take over the work of transformation.

And we are seeing everything from the removal of traffic violation from policing, as has happened in Berkeley more recently — we are seeing the public health authority being called upon to take greater responsibility for delivering community-based violence interruption and community-based — or, trauma-centered harm reduction. And I think these are all what we can imagine at this moment for bringing forward transformation.

But the bottom line is, we’re probably not yet there for the full possibilities of what is to come. And so, we have to expect, over the coming weeks, months and years, that people will be experimenting on the ground, will be trying things new. But this is going to ultimately be about political accountability for elected officials, because that’s where the legislative change has to happen.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Khalil, I wanted to ask you — in an information society like ours, people tend to make a fetish of statistics, and crime statistics are often used by politicians. Could you talk about Frederick Hoffman, how he misused statistics to demonize Black people?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Sure. Well, in this day and age, we are having a conversation about crime statistics as an index of the threat and danger that Black people pose, when we are listening to a lot of political elites and particularly police officials. While we’re not having this conversation today, if we had a counterpoint, that counterpoint would be that since George Floyd was killed, the spike in violence that occurred across major cities in this country is itself evidence, prima facie evidence, statistical evidence, that Black people are in need of more policing and not less policing. And this is the legacy of Frederick Hoffman, to make the argument that the evidence of crime that happens or violence or harm that happens within the community is evidence of the dysfunctionality and the dangerousness of that population.

But that’s a lie, and it’s always been a lie, because the violence within that community is itself a symptom of the violence of the state and the violence of a society that was focused on extraction and exploitation of people. And why do we know this? Because it wasn’t just Black people who experienced this. It was white people. You have European immigrants that experienced this. And about a hundred years ago, the same people that produced statistics recognized that they should see violence as symptomatic of a capitalist society that is grinding people and that is committing acts of violence in the economy itself. And how to fix that was not through policing. How to fix that was to invest in those communities with pro-social interventions, to give people the economic security, the collective bargaining rights, the right to be seen and to simply be, as I — again, to quote my colleague Kelly Lytle Hernández.

So, we are still living with Hoffman. Hoffman’s legacy in defining crime statistics among Black and Brown people as evidence of their dangerousness, and then driving policing as the response to that, is still the legacy we live with. It is the infrastructure that we, many of us, are trying to dismantle.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you so much for being with us. And I just want to end — again, you’ve got the three guilty verdicts on Chauvin, and then, in Columbus, Ohio, right at the time the verdicts were being read, many inside watching those verdicts, a police officer fatally shot four times a Black teenage girl, 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant.

That does it for our show. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, thanks so much for being with us, professor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, author of The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Stay safe. Wear a mask.

Media Options