Topics

Guests

- Charles Pillerthe lead reporter on the Los Angeles Times investigative team that broke this story. He joins us from Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles Times has revealed the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has made millions of dollars each year from companies blamed for many of the same social and health problems the foundation seeks to address. We speak with the lead reporter on the L.A. Times investigative team that broke the story. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

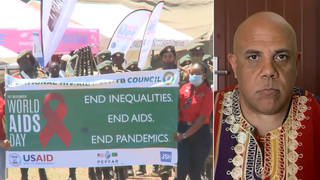

AMY GOODMAN: Is the world’s largest private philanthropy causing harm with the same money it uses to do good? That’s the question hanging over the charity of Microsoft founder Bill Gates and his wife Melinda today. The Los Angeles Times has revealed the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has made millions of dollars each year from companies blamed for many of the same social and health problems the foundation seeks to address.

The Gates Foundation has an endowment of more than $31 billion. The investment mogul Warren Buffett has pledged an additional $30 billion delivered in incremental sums. Since its inception six years ago, the foundation has committed more than $11 billion to programs around the world. This includes major grants for vaccine and immunization programs, HIV and AIDS research, and public education here in the United States.

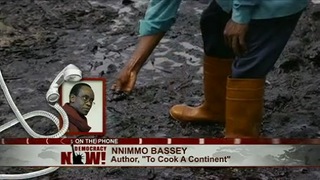

But the L.A. Times investigation reveals the Gates Foundation’s humanitarian concerns are not reflected in how it invests its money. In the Niger Delta, where the foundation funds programs to fight polio and measles, the foundation has also invested more than $400 million in companies like Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron. These oil firms have been responsible for much of the pollution many blame for respiratory problems and other afflictions among the local population.

The Gates Foundation also has investments in 69 of the worst polluting companies in the U.S. and Canada, including Dow Chemical. It holds stakes in drug companies whose drugs cost far beyond what most AIDS patients around the world can afford. Other companies in the foundation’s portfolio have been accused of transgressions including forcing thousands of people to lose their homes, supporting child labor, defrauding and neglecting patients in need of medical care.

Overall, the L.A. Times says nearly $9 billion in Gates Foundation money is tied up in companies whose practices run counter to the foundation’s charitable goals and social mission. And that number may be understated. The Gates Foundation has not provided details on more than $4 billion in investments it says are loans.

The Gates Foundation refused to talk to the L.A. Times about specific investments and whether it planned to change its practices. We also contacted the Gates Foundation for comment, but we didn’t get a response.

Charles Piller, the lead reporter on the Los Angeles Times investigative team that broke this story, joins us now from Los Angeles. We welcome you to Democracy Now!

CHARLES PILLER: Thanks very much.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good to have you with us. Why don’t you start out where you began your two-part series, and that is in Nigeria with a 14-month-old boy named Justice. Tell us about him.

CHARLES PILLER: Yes, well, the region of the Niger Delta, of course, is a very important economic zone for Nigeria. It’s where the vast majority of their oil and gas is generated. And as a result, American companies and other European companies, as well, have been given pretty much a free rein in developing oil in what is unfortunately a very unstable and often corrupt environment.

The angle that we looked at specifically, of course, is that we wanted to see whether the charitable goals, the very noble goals, of the Gates Foundation, namely in Nigeria trying to eliminate polio and measles, were in any way undermined or affected by some of their investments in the oil companies that are so important as an economic force in that region. And Justice Eta, the baby that was featured in our story, lives in a village, more like a shanty town, called Ebocha, which is — the name Ebocha means, in the local language, “city of lights.” And the lights are gas flares that are blazing 300 feet into the air, day and night, from an oil plant operated by the Italian oil giant Eni. And these flares spew into the atmosphere, not just soot, but toxic chemicals that cause a tremendous range of health problems among the local people. The fumes and the soot are so pervasive that farmers go several kilometers away from the oil plant in order to plant their crops, because otherwise they’re covered with pollution, and therefore, they can’t sell them in the marketplace.

So we took a look at what kinds of problems are caused by these companies that the Gates Foundation has hundreds of millions of investments in and tried to ask a pretty basic question: Is it fair to look at the endowment investments of the Gates Foundation and ask whether the results of those investments are offsetting in a significant way the very noble and important charitable goals that they’re accomplishing with their donations? And I’m afraid to say that in Ebocha, in the Niger Delta, and throughout the world, we found compelling evidence that that indeed was the case.

AMY GOODMAN: You interview a doctor, where Justice lives, named Dr. Elekwachi Okey, who talks about the hundreds of flares at these plants. Tell us more about him and his patients.

CHARLES PILLER: Well, my colleague Edmund Sanders interviewed Dr. Okey, and he’s someone who is on the ground there and sees the results of the pollution in the health of the people there, not only problems like asthma or undifferentiated respiratory problems. But also, I think one of the key things that, to us, seemed quite important is that the specific goal of the Gates Foundation in Nigeria is to eliminate polio and measles. And polio, in particular, as some viewers may know, the epicenter of the remaining polio outbreak in the world is in Nigeria, so it’s a crucial area for reducing the incidence of polio and is part of a worldwide campaign to eradicate the disease.

And the problem is that the pollution from these plants, which is so pervasive throughout the countryside, not only causes respiratory problems, but also has the effect, according to health authorities in Nigeria — and I might add that their views were validated by scientific studies that we were able to find — that these pollutants actually reduce immunity and make the children that are being vaccinated more susceptible to diseases like polio and measles than they otherwise would be. Moreover, many of the parents of children in this area are reluctant to vaccinate children who are suffering from respiratory ailments. They feel that the vaccinations may further weaken their children, rightly or wrongly. And ironically, these are vaccinations that are very important to the children.

So what we were able to determine was that there’s no pure balance sheet in these matters. It’s difficult to know exactly how much the good works of the Gates Foundation in Nigeria are offset by this pollution. But what we do know is that they are contributing on both ends of the problem, and that, we found, was something that in itself would not be a problem if the foundation were examining its own investments carefully.

AMY GOODMAN: We should point out that the kind of flaring you’re describing, by the way, in the Niger Delta, in some cases done by U.S. companies like Chevron, is not allowed in the United States. It’s illegal, because of the kind of pollution that it puts out.

CHARLES PILLER: It’s not. It’s actually — there is a bit of flaring in the United States, as well, but it’s on a much smaller scale, and it’s tightly controlled, and it is done in a way that less pollution results from it. The Niger Delta flaring is by far the worst in the world. Out of all the gas flaring that’s done in the world — and you have to understand that the reason that this flaring is done is that it’s cheaper for the oil companies to burn off this gas that occurs with oil deposits that they are drilling. And in developed nations, they would trap the gas and either re-inject it into the ground or capture it for sale. In Nigeria, where there isn’t a well-established market more natural gas, they prefer to just burn it off and get the oil out.

AMY GOODMAN: Charles Piller, we only have a few minutes, and you’ve done such extensive reporting here. I want to get to a number of the cases you cite, but the issue of the firewall, the kind of, I think it’s called, blind-eye investing, the Gates Foundation pouring money into these philanthropic endeavors, yet at the same time are pouring money into investments in these polluting corporations.

CHARLES PILLER: Yes. I think the fundamental issue here is that American foundations, because of tax laws, generally give away about 5 percent of their net assets every year. And this allows them to avoid most taxes. The other 95 percent is invested. It’s invested in a wide range of securities, stocks, bonds. And the reason why a wide range is used is that obviously a prudent investor wants to protect their investment.

Now, the issue that we found is that the Gates Foundation established a firewall between the people who manage its investments and the people who give away its grants, and as a result, there is no coordination made so that the investments don’t tend to contravene the grants and the charitable goals of the foundation. And so, as a result, what we found is that the 95 percent that’s invested every year, in large measure, tends to go to industries, to companies that not just may be doing some harm, because, frankly, a lot of companies do harm in the world, and it’s a difficult thing to police at times, but they go to companies that in many cases directly engage in activities that tend to subvert the charitable goals of the foundation, not just in the pollution angle.

But we found, for example, $1.5 billion approximately in foundation investments in pharmaceutical companies whose practices tend to price their AIDS drugs out of reach of the very people that the Gates Foundation has decided are its highest priority to help: AIDS victims in the developing world who can only afford a very meager price for AIDS drugs, but are unable to afford the drugs from companies that the Gates Foundation is making hundreds of millions of dollars in profit from.

AMY GOODMAN: Charles Piller, we have less than two minutes. And in your second piece, you begin your piece, “Gates Foundation Invests in Firms Accused of Abuses,” about a couple, Cheryl and Jeff Busby, and Ameriquest. Please quickly describe that story.

CHARLES PILLER: Yes, well, one of the highest priorities for the Gates Foundation has been service programs within the Pacific Northwest, their home. And, in particular, they’ve attacked homelessness and housing instability as a key goal. What we found is that, as the Gates Foundation is giving tens of millions of dollars to assisting people in unstable housing and poor people who need help and homeless people, they are also invested to the tune of well over $2 billion in companies that are in what’s called the subprime loan industry.

Now, this is an industry that is designed to serve people who have less-than-perfect credit and still want to be homeowners. But this industry has been rife with abuse for many years, and as a result, many of the investments are contributing to the financial well-being of the Gates Foundation and to the companies that have been implicated widely in abuses of lending that have resulted in people losing their homes, thousands and thousands of people losing their homes all throughout the Pacific Northwest and throughout the country.

The Busbys are one example of that, a poignant example because Cheryl Busby works for an agency that was given donations by the Gates Foundation, in part to counsel victims of predatory lenders, victims of the subprime industry. And this same — the company that was a predator in their case, Ameriquest, was implicated as a predator in their case, is also a company that the Gates Foundation is profiting from as an investor.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there. Charles Piller, Los Angeles Times reporter — two-part series on the Gates Foundation — I want to thank you very much for being with us. We’ll certainly link to it at our website, democracynow.org. [part one, part two]

Media Options