Guests

- Alec Karakatsanisfounder of the Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit organization challenging systemic injustice in the U.S. legal system.

- Krish Gunduexecutive director of the Texas Jail Project.

- Stew StewartTony Award-winning musician and playwright.

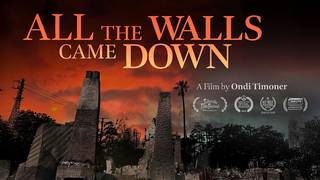

The new short film Criminal highlights the injustices of the criminal legal system with a look at how for-profit bail preys on the poor and mentally ill. We’re joined by three contributors to the film, musician Stew Stewart and bail reform advocates Krish Gundu and Alec Karakatsanis, to discuss how what Karakatsanis calls the “unconstitutional” system of cash bail leads to “millions of coerced guilty pleas every single year all across the country, just because people are so desperate to get out.” Criminal focuses on Texas’s notorious Harris County Jail, where at least 15 people have died in pretrial detention just this year. Gundu explains, “We have criminalized mental illness. We’ve criminalized homelessness. We’ve criminalized reproductive rights. And so, the jail has become the emergency room of our community.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: “Criminal” by Stew Stewart from the soundtrack of the new documentary Criminal, which we’ll talk about in a minute.

This year, President Trump signed two executive orders that aim to eliminate so-called cashless bail, and threatened to cut federal funding to Washington, D.C., and other jurisdictions that keep the policy in place. Cashless bail, a system in which people accused of minor offenses are released from jail while awaiting trial without having to pay a specific cash amount, because they can’t afford it.

Next month, Texans will vote on Prop 3, which would amend the state’s Constitution to allow judges to deny bail to people charged with certain felonies. This comes as at least 15 people have died in the Harris County Jail in Houston, Texas, this year, including just two this month. Most people in jail have yet to go to trial but cannot afford to pay bail for their release.

Now a new animated musical documentary short film called Criminal is drawing attention to the crisis. This is the trailer.

STEW STEWART: More than 9,000 people dwell

in this waterfront property.

Its impressive facade might compel

or inspire those with the dough to peek in and inquire.

Who wants a condo with a wonderful view

right here in downtown Houston?

Follow me, I’ll show you.

Upon closer inspection, let me lift the veil

on the third-largest hell in America,

the Harris County Jail.

ALEC KARAKATSANIS: One thing that a lot of people don’t

appreciate about Harris County Jail

is that it looks very beautiful from the outside.

It’s overlooking the bayou

and the water in downtown Houston.

There’s all of these windows.

One thing people don’t understand

is that these windows are fake.

STEW STEWART: Windows without a view,

a metaphor too perfectly sad to be true.

ALEC KARAKATSANIS: That, in a nutshell, really captures the facade,

the veneer of what we call justice.

STEW STEWART: Criminal justice.

It’s criminal, criminal, my crime.

Time to open up your Harris County windows.

AMY GOODMAN: The trailer for Criminal. And this is a clip from the new film, which features Alec Karakatsanis, author of Copaganda, who we’ll hear from in a minute. This clip begins with a call from a Harris County Jail prisoner.

MALE 5: I have as of today,

been incarcerated for over 13 months.

My next court date is not until the last week of July.

That’s six months of dry sitting in jail

for a so-called crime I never committed.

Now I’m ready to become a felon just to get outta jail

or at least get this train moving.

That’s one year already wasted.

STEW STEWART: But most of us don’t go to trial.

ALEC KARAKATSANIS: The money bail system

The money bail system

The money bail system is built to coerce guilty pleas.

In Harris County, Texas, in misdemeanor cases,

if you’re too poor to afford a couple hundred dollars

to get out of jail,

you plead guilty 84% of the time

and you do so in about 3.2 days.

STEW STEWART: It’s too expensive to be innocent.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from the animated musical documentary short film Criminal, which was published this month on The New Yorker magazine website.

Democracy Now!’s Nermeen Shaikh and I recently spoke to three people involved with the film.

Stew Stewart, Tony Award winner, singer-songwriter, behind the critically acclaimed Broadway musical Passing Strange, his music and lyrics are featured in Criminal. He’s a professor of the practice of musical theater writing at Harvard.

Krish Gundu is executive director of the Texas Jail Project.

And Alec Karakatsanis is the founder of the Civil Rights Corps and author of Copaganda: How Police and the Media Manipulate Our News.

We began by asking Alec about his comment in the film that, quote, “There is no presumption of innocence in practice in the American legal system if you’re poor.” This was his response.

ALEC KARAKATSANIS: Every single night, and right now as we’re talking, there are hundreds of thousands of human beings in jail cells all over this country solely because their families lack cash to pay for their pretrial release. The United States and the Philippines are the only two countries in the world that have a for-profit, commercial money bail industry, which means that in the vast majority of cases all over the country every single day, the reason that children are separated from their parents, the reason people are taken away from their homes and jobs and schools and churches and communities, is not that anyone has determined that they’re a danger to the community or anyone has made a reasoned decision based on evidence that they should be jailed, but because they lack access to cash.

And what this ends up doing is it ends up creating millions of coerced guilty pleas every single year all across the country, just because people are so desperate to get out, because they’re deprived of their medication, there’s no one to take care of their pets, they don’t know where their children are. All of these, these horrific things are happening to people in this country solely because they lack access to pay for pretrial money bail. And this is unconstitutional, and it’s the work that we’ve devoted ourselves to over the last decade at Civil Rights Corps.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Krish, could you speak about your work? You are co-founder and executive director of the Texas Jail Project, and you’re featured in this documentary, as well. If you could talk specifically about what you know of what happens at Harris County Jail?

KRISHNAVENI GUNDU: So, Harris County Jail is the largest warehouse of people with mental illness in the state of Texas. Every time I say that, I find it so hard to believe, but that is what we have decided to do as a society, is to invest in punitive solutions to public health issues. So, today, if you look at the Harris County Jail dashboard, out of the 8,763 people that are being held in jail, 78% are tagged as psychiatric — 78%. So we’re the largest warehouse of people with serious mental illness in the state of Texas, not a state hospital, not any kind of psych facility, but a county jail, where the pretrial detention percentage is 67.8%. So, what we’re essentially doing is we’re locking people up for their illness. We have criminalized mental illness. We’ve criminalized homelessness. We’ve criminalized reproductive rights.

And so, the jail has become the emergency room of our community. And as a result, what you see are all these horrific deaths in our jail. So, this year we’ve had — this calendar year, we have had 15 reported deaths — 15. Out of that, at least six were people who had cycled through both the mental health and the jail system for years and years and years and never received the appropriate level of care that they needed. And also, the people who died in our jail disproportionately are people with serious mental illness and medical issues, and so they can’t advocate for their medical needs, which is why they end up in sort of horrific tragedies.

And I’ll give you one quick example of one of the deaths this year. Young man, 39 years old, he struggled with severe schizophrenia, and he died of a completely treatable throat infection, just a simple strep throat infection, because he was not able to advocate for himself. And when we got his records and his autopsy report, his medical records and autopsy report, it turned out that he had starved to death because his throat closed up. So, those are the kind of deaths that we’re seeing in our jail.

AMY GOODMAN: Stew, I wanted to ask you about your collaboration with Thomas Curtis. He was incarcerated for 11 years. How does his experience affect the visual language of the piece, this very unusual collaboration between, you know, a regular documentary exposing the Harris County Jail and it almost being a kind of really profound music video?

STEW STEWART: Well, it’s actually far more unusual than you could even imagine, because when Heidi and I were creating the music, we never saw a single frame of what Thomas was doing. And that seems shocking to a lot of people, but I actually think the fact that we were working independently meant that we were investing deeply in the music and doing our best to serve the truth of the film, and we weren’t worried about serving an image. And Thomas didn’t have to necessarily worry about serving the music. He was just doing his thing. We were doing ours. And there were no conversations. There literally were no conversations. We just — both parties just did what they do, and you see the result.

AMY GOODMAN: Had you known about the Harris County Jail system before you wrote this musical piece? It opens with you describing this Harris County Jail in downtown Houston that looks like a high-rise with windows. And as you sing about it —

STEW STEWART: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — there are no windows, actually. Those are not windows.

STEW STEWART: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, turning the — turning the facts into lyrics was, you know, incredibly challenging and worrisome sometimes. But the thing is, I come from Los Angeles, so I grew up in Daryl Gates’s, you know, LAPD. You know, I was bailing friends out of jail by pawning my guitar amps while I was still in high school. So, I grew up with this. So, that part, I was familiar with. From a Los — from the police state that Los Angeles was that I grew up in, I was very familiar with this. I was not familiar with Houston specifically, but the feeling of what was going on was absolutely something I was completely familiar with, and still am.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to another clip from Criminal that looks at the conditions at the Harris County Jail during COVID-19 pandemic.

STEW STEWART: And then COVID hit.

KRISHNAVENI GUNDU: Some of these men filed a civil lawsuit

just to get mops and brooms.MALE 7: Yeah, after four weeks of sweeping with newspaper

and mopping our pod with our towels,

yeah, we got 26 in the cell.

And often the food is tossed in there,

through or under the door.

And sometimes the guards count wrong

or other prisoners even take more of the money

before everyone gets theirs.MALE 8: I spent seven days in quarantine,

which meant solitary confinement.

I was supposed to get out an hour once a day,

but with 26 cells all in a row,

if the guards changed shifts before they got to my cell,

sometimes they missed me

and I’d be in there for 36 hours straight.

It was hell.

Sometimes they’d have me go alone for more than a day

with no food, no lounge time.

Two prisoners died while I was in there.

AMY GOODMAN: Harris County Jail issued this statement in response to the film. “Harris County implemented aggressive health measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in the jail in spite of the crowded conditions. As a result, the jail’s COVID-19 mortality rate was far below the mortality rates reported in other major U.S. jails. In fact, the overall mortality rate for the Harris County Jail has consistently ranked below the state and national jail average, including in 2022.” Krish Gundu, can you respond to this?

KRISHNAVENI GUNDU: I think the national mortality rate, that whole conversation, is a distraction. It is a distraction from what is actually happening in our jails. It has been happening since way before COVID and has been happening through COVID and post-COVID.

If you look at the kind of deaths that happen in our jail — and I don’t know if you caught this earlier — the number of people who are dying in our jail, there’s a disproportionate number of them who have serious mental illness and disabilities. These are people who cannot advocate for themselves. And so, instead of just looking at the numbers, we need to look at the stories.

And I’ll tell you a real quick story — two stories, if you have time for it. One, a young man, 39 years old, who died in our jail, he had severe schizophrenia, and he died of a perfectly treatable throat infection. He had a strep throat infection, which was easily treatable. But because he couldn’t advocate for himself because of his schizophrenia, nobody knew that he was sick, and he died. And when we found the autopsy report in the medical records, we found that he had actually starved to death because his throat had closed up. So, that’s the kind of death that’s happening.

The other one that I want to share with you is this person who was arrested on criminal trespass, the kind of charge that they should not be holding people in jail anymore. And he was arrested in acute psychiatric crisis. He should have been sent to the hospital. But instead, they kept him in a single cell, in a padded cell, used multiple restraints on him. And he still managed to kill himself by repeatedly hitting his head on the metal grate in the floor, over and over again, while the jail staff watched. And the jail was never found noncompliant.

And the point I’m trying to make with that is that that would not happen in a psych facility or in a hospital. But those are the kind of people that we are willing to book in our jail and let and watch them die, and then talk about mortality rates. It doesn’t matter if the mortality rate is lower. What matters is the kind of deaths that we are seeing, which are completely preventable. These people should have never been confined and booked into our jail, the kind of people that we’re seeing who are dying.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Krish Gundu, if you could talk about, you know, the extent to which Harris County Jail is representative of what’s happening in other county jails across Texas?

KRISHNAVENI GUNDU: So, the Harris County Jail is very representative of what’s happening across the county jail system. In fact, the state has multiple times — you know, the Texas Association of Counties, the Legislature, all the state regulatory agencies, they all casually throw out this fact that the Texas county jail system is the largest warehouse of people with mental illness in the state of Texas. This is an accepted documented fact at this point. And Harris County Jail happens to be the largest of that. In fact, the top three out of the top five populations of people with mental illness are county jails in Texas. So, what you see in Harris County is happening across the state. We had — we had several people dying of water intoxication in Dallas and Fort Worth, and dehydration and starvation. I mean, these are not things that would happen in regular psych hospitals. But we have — the state has pushed its mental health crisis into the jails, and so we are beginning to see all these horrific, horrific deaths across the state in county jails.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is another clip from Criminal.

STEW STEWART: George Floyd spent 10 months

in the Harris County Jail before he left Texas

and went north to Minneapolis

in search of a better life.ALEC KARAKATSANIS: One sad fact

of our modern American punishment system

is that you can spend 10 months

in the Harris County Jail like George Floyd did,

a place of unspeakable horror.

And you can think to yourself, I need to go somewhere

where I’m gonna find a different way of life.

I’m gonna go somewhere where the same

injustices don’t plague every single day of my existence.

And yet there’s nowhere you can go in this country

where these problems don’t exist,

because there is not a single city or state in this country

where the criminal punishment bureaucracy is functioning

in a way that promotes well-being and safety

and flourishing of people in communities.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that clip, we hear the music of Stew and Heidi, and Alec Karakatsanis, who is the author of the book Copaganda: How Police and the Media Manipulate Our News. So, if you can move, Alec, from the Harris County Jail and this story of George Floyd spending 10 months there before he was finally released and went on to the Twin Cities, and talk about what’s happening in this country, and in light of the militarization of cities in this country, the number of people we may see increase in jail, not able to get out simply because they don’t have bail money? Talk about the significance of all of this, what what you call “copaganda” has to do with this.

ALEC KARAKATSANIS: I think we have to put all of this into context, right? So, the United States right now is putting Black people in jail cells at six times the rate of South Africa at the height of apartheid. We are putting all human beings in jail at about six times the rate of other comparable countries and six times the rate of our own steady historical average from the time of the founding up until about 1980. So, when you have that kind of massive bureaucratic system, it’s actually quite difficult to transition 10 million human beings every single year into this kind of punishment bureaucracy system. It takes an enormous amount of effort. It takes public defenders and prosecutors and judges and probation officers and parole officers and police officers and prison guards, etc., etc.

But also it provides an incredible opportunity for profit. There are multibillion-dollar industries at every single stage along that system, from the production of the metal chains and the jails and the hand — and the sort of Tasers and the guns, but also the software and the facial recognition algorithms and all of the sort of things that police and technology that the prosecutors have to use, etc., etc. So, every single one of these — look at Harris County Jail, for example. There’s a multibillion-dollar prison and jail telecom industry. So, there’s all of these interests that have an incentive to keep expanding the punishment bureaucracy.

And in addition, when you have this kind of metastasized system, you have to tell the public a certain story about what it’s doing, because no society in the recorded history of the modern world has ever tried to take so many people who live in it and lock them up. And this is a story that needs to be told in a really persuasive way, because most people, when they just first encounter this, they think, “How is this possible? How is it possible that a country that has really beautiful messages, you know, inscribed on its marble monuments, and it has all this commitment to liberty and due process — how is that reconciled with the greatest incarceration machine that the world has ever seen?”

Well, this is where copaganda comes in. It’s a series of mythologies that are created to tell people that the real purpose of the system is not profit, it’s not control, but it’s actually safety and even justice. So, a lot of people use the term “criminal justice system.” I don’t use that term. I call it the “punishment bureaucracy,” because I think the “criminal justice system” is another sort of term of copaganda. It’s designed to make us think that what’s happening here has either the purpose or the effect of doing justice.

And so, I think what copaganda really does is three main things. First, it narrows our conception of safety and threat, so it has us really, really worried about only a very narrow range of the harms that happen in our society, particularly harms that the police associate with poor people, unhoused people, people of color, particularly Black people, immigrants and strangers — right? — so has us really, really worried about the person next to us at Walgreens or the person that we walk down the street and see from afar — right? — when, in fact, most interpersonal harm in our society is committed by people who know each other. Most physical and sexual violence is perpetrated by people who have a relationship with each other. And so, copaganda has us really afraid of all those things, but ignoring the far larger harms in our society, like wage theft, which is about $50 billion a year. That’s like five times all property crime combined. And yet the news media focuses on a tiny amount of shoplifting, even if shoplifting is actually down. It also ignores air pollution. Millions of criminal acts of air and water pollution kill 100,000 people a year. That’s five times all homicide combined. But we’re taught to really not focus on that and to narrow our conception of safety and threat.

And the second thing copaganda does is, once it’s narrowed our conception of threat, it tells us that those threats from those marginalized people are constantly increasing and increasing and increasing. So people think crime is up every year, even though it’s been going down and we have historic lows.

And the final thing that copaganda does, that I really focus on in the book, is it tells us that the solution to all of those fears is more and more and more and more investment in the bureaucracy of punishment and police prosecution, prison sentences. And this is kind of like a modern flat-Earther mythology. It’s completely contrary to all of the evidence. What the evidence shows is the amount of interpersonal harm in any given society is largely determined by root structural causes, like levels of inequality and poverty and access to healthcare and housing, levels of loneliness and isolation versus community connection, toxic masculinity, exposure to toxins like lead in children.

And that’s what copaganda does — right? — is it focuses on the wrong problems and the wrong solutions to those problems, to create a culture of fear that turns people against the most vulnerable people in society, so that the people who own and control things in our society can develop the tools of surveillance and punishment and repression that can preserve distributions of wealth and power in a society.

AMY GOODMAN: _Criminal is a short animated musical documentary featuring the musician Stew Stewart, who wrote the music with Heidi Rodewald; Krish Gundu, executive director of the Texas Jail Project; and Alec Karakatsanis, founder of the Civil Rights Corps and author of Copaganda: How Police and the Media Manipulate Our News. You can watch Criminal on The New Yorker magazine website and YouTube channel.

That does it for our show. Democracy Now!'s Nermeen Shaikh is speaking Saturday in St. Louis. You can check it out at democracynow.org. I'm Amy Goodman. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report.

Media Options