Guests

- Sarah Harrisoninvestigative editor of WikiLeaks and acting director of the newly formed Courage Foundation. In 2013, she accompanied NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden on his flight from Hong Kong to Moscow and spent four months with him in Russia.

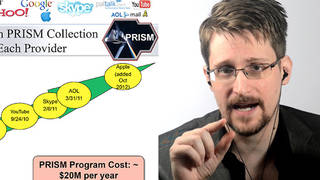

In the latest revelations from documents leaked by National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, The Washington Post has revealed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court secretly gave the National Security Agency sweeping power to intercept information “concerning” all but four countries around the world. A classified 2010 document lists 193 countries that would be of valid interest for U.S. intelligence. Only four were protected from NSA spying — Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The NSA was also given permission to gather intelligence about the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the European Union and the International Atomic Energy Agency. As we broadcast from Bonn, Germany, we are joined by Sarah Harrison, investigative editor of WikiLeaks, who accompanied Snowden on his flight from Hong Kong to Moscow last June. She now lives in exile in Germany because she fears being prosecuted if she returns to her home country, the United Kingdom. Harrison describes why she chose to support Snowden, ultimately spending 39 days with him in the transit zone of an airport in Moscow, then assisting him in his legal application to 21 countries for asylum, and remaining with him for about three more months after Russia granted him temporary asylum. She has since founded the Courage Foundation. “For future Snowdens, we want to show there is an organization that will do what we did for Snowden — as much as possible — in raising money for legal defense and public advocacy for whistleblowers so they know if they come forward there is a support group for them,” Harrison says.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from Bonn, Germany, from the Global Media Forum. Well, The Washington Post has revealed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court secretly gave the National Security Agency sweeping power to intercept information, quote, “concerning” all but four countries around the world. A classified 2010 document leaked by Edward Snowden lists 193 countries that would be of valid interest for U.S. intelligence. Only four were protected from NSA spying: Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The NSA was also given permission to gather intelligence about the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the European Union and the International Atomic Energy Agency. According to The Washington Post, the secret document indicates that academics, journalists and human rights researchers living in the United States and abroad could all be targeted under the order.

Well, we turn now to a Democracy Now! global broadcast exclusive. We’re joined here in Bonn, Germany, by Sarah Harrison of WikiLeaks, who accompanied Edward Snowden on his flight from Hong Kong to Moscow last June. She spent 39 days with Snowden in the transit zone of an airport in Moscow while she assisted in his legal application to 21 countries for asylum. Sarah Harrison then remained with Snowden for about three more months after Russia granted him temporary asylum. Sarah Harrison is investigative editor of WikiLeaks and acting director of the newly formed Courage Foundation.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! And thanks so much for doing this interview. You’re living in Berlin, Germany, right now, but you’re from Britain.

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Why not go home?

SARAH HARRISON: Britain has a Terrorism Act, which has within it a portion called Schedule 7, which is quite unique. What it is is it gives officials the ability to detain people at the border as they go in or out or even transit through the country. And this allows them to question people on no more than a hunch, giving them with no—giving them no right to silence. It also was the case of no right to a lawyer, as well, though that’s starting to be changed. But you’re compelled to answer their questions. All the legal advice received is that the likelihood is very strong that I would be Schedule Sevened, detained under this and questioned, because of my work with WikiLeaks and Snowden. There are certainly answers, for source protection reasons, that I would be unable to answer, which would make me committing a crime upon returning home.

AMY GOODMAN: This is what happened to Glenn Greenwald’s partner David Miranda.

SARAH HARRISON: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: Glenn Greenwald who met, of course, with Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras in Berlin and wrote the first articles about the documents.

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah, he was actually just transiting through the country. He was—through the U.K. He had been in Berlin. He was going back to Glenn in Rio, in Brazil. And he was just transiting through the U.K. The U.K. officials got intel that he might have some information that was of benefit, they decided, to their terrorism investigation, and so they detained him under this, and he was compelled to answer all of their questions.

AMY GOODMAN: And held for many hours.

SARAH HARRISON: He was held for the full nine hours.

AMY GOODMAN: Before they would have to arrest him, if they held him any longer.

SARAH HARRISON: Arrest or release, yes. And he was not entitled to a lawyer or anything that full time.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Sarah Harrison, how did you end up with Edward Snowden on that flight from Hong Kong to Russia?

SARAH HARRISON: Well, he reached out for help, and we were uniquely in a position to help for several reasons. We have a history and an understanding of what it is to be in a position where you’re being persecuted, where you’re dealing with the government of the United States getting their full force down upon you. We have a number of connections—legal, diplomatic—around the world. And I have a lot of contacts in Hong Kong, so I’ve been there many times. So I was able to operate there knowing the city, when maybe others would be unable.

AMY GOODMAN: So you got there after he was speaking to Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, as the articles were being released?

SARAH HARRISON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And then what happened? You were meeting him for the first time?

SARAH HARRISON: Yes, I had not met him before. So, well, we worked to find out the legal situation, the legal options, to negotiate his ability to exit the country and to ensure that he would have as high a probability of asylum and safe passage in other places around the world.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how did you make it from—I mean, he was at the hotel with Glenn and Laura. He then was taken by human rights lawyers to be protected as the media found where they were. How did you even make it to the airport? Were you concerned that he would be arrested in Hong Kong at the behest of the United States?

SARAH HARRISON: Well, when we left, the United States had just put in an extradition request for him. The process is that this has to go through the court system there and be approved or be denied. We actually left before it had finished going through the Hong Kong court system, so there was no illegality about his departing the country.

AMY GOODMAN: And if he had been arrested in Hong Kong, what would have happened?

SARAH HARRISON: So there were two things at play. He had the ability to put in an asylum request. Hong Kong then would obviously have had to have decided what its decision on this asylum request was. They actually have a history of taking a very long time to do this. The problem with his case would have been that if, as it did, the extradition request came in, and if—when it was approved, he would have to be arrested and then held in prison whilst either the extradition request or the asylum were being decided which avenue they would take. And because often the asylum takes so long, he would be held in prison for an awful long time.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you get on this plane with him in Hong Kong. And why did you end up in Moscow?

SARAH HARRISON: Choosing the route to take, the aim was to get to Latin America—Ecuador, specifically.

AMY GOODMAN: Because they were granting him asylum?

SARAH HARRISON: They were obviously positive towards the granting of asylum.

AMY GOODMAN: As they had done with Julian Assange—

SARAH HARRISON: As they had done with Julian.

AMY GOODMAN: —who’s in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London?

SARAH HARRISON: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: And was Julian helping you with this whole—

SARAH HARRISON: Very much so, very much so.

AMY GOODMAN: So, really, you, WikiLeaks and Julian facilitated Snowden making it out of Hong Kong.

SARAH HARRISON: And gaining asylum, yes. The reason for going via Russia was that, obviously, we needed to have a safe flight route. You can’t actually get direct from Hong Kong to Latin America. Normally, flights to Latin America go through the United States or Western Europe. And this was obviously not an option in this case, so hence the sort of seemingly bizarre route via Russia and Cuba on to Latin America.

AMY GOODMAN: So you weren’t planning to stop in Russia, but what happened?

SARAH HARRISON: No. Well, whilst we were in the air, as soon as we’d left, Hong Kong announced that he had left, I think, in an ability to sort of say, you know, “Stop hassling us. He’s gone. He’s not here anymore.” So then the United States made very public announcements about how they had canceled his passport, and if any—you know, any onward travel therefore would be without any valid documentation. So we were essentially stranded by the U.S. government in Russia.

AMY GOODMAN: And you stayed in the airport for?

SARAH HARRISON: For 39 days. Well, he didn’t—we didn’t have a visa. I mean, that was not—that you can transit through without needing a visa as long as you’re under 24 hours within the airport. So, hence, we had no visa to remain in Russia, so he couldn’t just walk on through. And so, we spent 39 days trying to get asylum in various places around the world, many, including Germany. And they were either turned down or ignored, the requests, for the most part. Latin America was very supportive, but the ability to physically get there safely at this stage was impossible, and so, hence, applying for temporary asylum in Russia.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to an interview I just did in Berlin when I interviewed Edward Snowden’s European lawyer, Wolfgang Kaleck, about the role of WikiLeaks and Sarah Harrison, our guest, in helping Snowden.

WOLFGANG KALECK: I think WikiLeaks was extremely helpful in the decisive phase in the beginning of the Snowden revelations. And especially Sarah, as a person, was extremely courageous, because going to Moscow is not—I mean, that’s not the easiest place in the world, and it’s not that they are waiting for us there. And so, going into this unsecure situation was extremely brave from Sarah. And I am very happy that she’s living now in Berlin, but I would be happier to know that she’s not facing a criminal charge because of what she did for Edward Snowden.

AMY GOODMAN: Is she facing a criminal charge?

WOLFGANG KALECK: We don’t know, because, I mean, many of these—many of these criminal investigations are secret, so we have no indication if or if not a criminal investigation is underway. But the risk at the moment is too high for her to travel back to the U.K., so she better stay in Germany. But I hope that this is not the end of the story.

AMY GOODMAN: That is Wolfgang Kaleck, the European lawyer for Edward Snowden. I was speaking to him in Berlin, Germany, this weekend. And he’s saying the stakes are just too high for you to go home. You made a big decision in engaging in this, and now you’re living in Germany. What made you make that decision?

SARAH HARRISON: A few reasons. One’s sort of a general ethical point that someone had done something so brave, and they should be supported, and I felt an empathy, a natural human empathy, and wished to support. Then there’s also the fact that, I mean, I work for a publishing organization. We obviously rely a lot on sources and believe in source protection. And the last example that the world had of how the U.S. government treats a high-value source is Chelsea Manning, who they put into a cage, was tortured, sentenced to prison for 35 years in the end. And I think it’s important for the world that you can speak the truth, you can blow the whistle, and you don’t have to end up in a cage; there are people that will support you, that there are people that will take risks for you, when you have risked so much, and you can have asylum in a country.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m looking at the letter that Eric Holder, the U.S. attorney general, wrote to the minister of justice of Russia requesting that Edward Snowden be extradited to the United States. And among the things Attorney General Holder says is, “First, the United States would not seek the death penalty for Mr. Snowden should he return to the United States. The charges he faces do not carry that possibility, and the United States would not seek the death penalty even if Mr. Snowden were charged with additional, death penalty-eligible crimes. Second,” writes Attorney General Eric Holder, “Mr. Snowden will not be tortured. Torture is unlawful in the United States.” Sarah Harrison?

SARAH HARRISON: I think that—I mean, when that letter came out, it was sort of rather extraordinary, when you’re looking at a country that has Guantánamo Bay. Chelsea Manning was—it was found by the U.N. special rapporteur on torture at the time, [Juan Méndez], that she had been tortured. So these claims were, as far as I could see, just empty rhetoric trying desperately to block any right to asylum that Snowden legally had around the world. They did this in a number of occasions. When we were looking at asylum in other countries, as well, they pre-emptively put in extradition requests to those countries, even though he wasn’t there, didn’t have asylum. So, I think that it’s an obvious pattern that the U.S. government chooses to try to initiate a pre-emptive attack to prevent people’s legal rights.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what happened to the Bolivian president, Evo Morales, as we go back. This is a year now that you accompanied Edward Snowden. When was it, within this period of going to Russia, that Bolivian President Morales’s plane was forced down in Austria by the U.S. government?

SARAH HARRISON: Well, we were still in the airport. There had been a number of presidents that had been Russia meeting with Putin. There was—and Morales was one of them. President Morales was one of them. And when his plane took off, there was the allegation that Snowden was on the flight, and the airspace around Europe shut down while he was trying to get across the continent. So here you see an extraordinary example of the U.S. dominance, where they’re able to get other supposedly sovereign nations to close their airspace because of supposed intel that they have, and a president’s plane, violating international agreements, is downed and was forced to come down in Austria.

AMY GOODMAN: All of these different countries participated.

SARAH HARRISON: Yes, a number. There was Spain, Portugal, France. There was a number of countries that participated.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, Austria had to accept him at the airport.

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah, yeah. I don’t think they’d go quite as far as having his plane run out of fuel and just crash to the ground, quite that far.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was your response, and what was Ed Snowden’s response, as you sat in the airport lounge where you were forced to be for five weeks?

SARAH HARRISON: It was obviously extraordinary, and still is, that a president’s plane would be downed. I think that it is something—these sorts of extralegal and extraordinary actions is something that WikiLeaks has seen on a number of occasions. The financial blockade—when we were publishing the war logs that started and started publishing Cablegate, there was an extralegal financial blockade against us. The fact that financial—supposedly independent financial companies will just cut off because of—cut off a publishing organization because of pressure from the U.S. government is, again, another extraordinary act that shouldn’t be happening within the rule of law.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about PayPal.

SARAH HARRISON: PayPal and these—MasterCard—

AMY GOODMAN: Cutting off any ability for WikiLeaks to get money through.

SARAH HARRISON: To receive donations, direct to us or actually via third parties that were collecting money for us. So this is quite an extraordinary, against-the-rule-of-law action that was taken due to pressure of the United States government. And it’s another—another example of this type of action can be seen with the downing of the plane.

AMY GOODMAN: Yet you set up the Courage Foundation, as you live here in Germany, to be able to support Edward Snowden’s defense fund.

SARAH HARRISON: Yes, for Edward Snowden’s defense and also for future Snowdens. We want to show that there is an organization that will do what we did for Snowden and as much as possible in raising money for legal defense, public advocacy for whistleblowers, so that they know when they—if they come forward, there is a support group there for them.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to a clip of Mike Rogers. This is in January. The House intelligence chair, Mike Rogers—not to be confused with Michael Rogers, now the head of the NSA—appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press and suggested Edward Snowden is a Russian spy.

REP. MIKE ROGERS: This was a thief, who we believe had some help, who stole information. The vast majority had nothing to do with privacy. Our Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines have been incredibly harmed by the data that he has taken with him and we believe now is in the hands of nation states. I believe there’s a reason he ended up in the hands, the loving arms of an FSB agent in Moscow. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mike Rogers, the head of the House Intelligence Committee. Sarah Harrison, your response, calling Edward Snowden a thief who purposely ended up in Moscow?

SARAH HARRISON: He certainly didn’t purposefully end up in Moscow. He’s not a spy or any of these words. I think that they come forward with this type of rhetoric to try and paint a picture which is completely untrue. And the facts of the case actually speak against that. What Edward Snowden did was inherently a patriotic act. He revealed this information to show to the American public that they are being spied on by their own government and that the government of the United States is breaking its own Constitution. And this is facts that they should know. And so, to call him a spy—well, if he’s a spy, it is only for the American public.

AMY GOODMAN: You got to know him very well, though you didn’t know him before, in the five weeks that you spent together at the airport and then months afterwards, before you left for Germany. Can you talk about how Ed Snowden described to you his motivations, where he had been before, joining the U.S. military, wanting to be in the Special Forces?

SARAH HARRISON: His history, I think, sort of speaks for itself, in that he’s always had a desire to serve his country. He’s always been very patriotic. And at the beginning, this played out with an understanding that the war in Iraq was legitimate, and he wanted to help and fight for his nation. Through his work then at the NSA and working as a contractor for the intelligence agency, he was able to understand that actually this isn’t necessarily—they’re not actually necessarily doing the right thing and telling the public the truth. And so his—although his same motives have always been the same, to serve his country and to uphold the Constitution, the method with which this was appropriate to actually act out became a very different one. And in this case, it became having to explain to the American public what was actually being done to them.

AMY GOODMAN: Had he reached out to WikiLeaks before?

SARAH HARRISON: We don’t talk about any sourcing, sort of, or any contact like that.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’re going to break, and when we come back, I want to talk to you about WikiLeaks, what it means to be the investigative editor for WikiLeaks, the fact that Julian Assange is now holed up in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. He was granted political asylum in Ecuador but cannot manage to get to Ecuador because the British government promises to have him arrested and extradited to Sweden if he steps outside the embassy. We’re talking to Sarah Harrison of WikiLeaks. This is her first global broadcast interview about that journey that she took, from Hong Kong to Russia, now to Berlin, where she lives, though her home is in Britain, where she is concerned she will be arrested if she tries to go home. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re on the road in Bonn, Germany, where we’re attending the Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum, where our guest today will be giving a keynote address on Wednesday. Our guest is Sarah Harrison. She’s the investigative editor of WikiLeaks. And I want to turn right now to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who just marked two years of confinement at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Assange has been holed up there since June 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he faces questioning on allegations of sexual assault. Actually, he says he doesn’t—he’s not trying to avoid extradition to Sweden, but concerned that if he ends up in Sweden, he will then be extradited to the United States. Speaking via satellite to a news conference in Ecuador, Assange thanked the Ecuadorean government and his supporters.

JULIAN ASSANGE: I am proud of keeping my promises to my sources, never buckling to pressure to censor our material, and having kept a publishing organization going in spite of significant pressure over the last four years, keeping up in the black despite an unlawful financial blockade, similar to the financial blockade of Cuba. Similarly, the Ecuadorean people can be proud that their country has stood up to intense pressure over myself and, indeed, many slanders from press associated with the United States and some associated with the United Kingdom. I am thankful for that resistance and also to the loyalty and resistance of my staff.

AMY GOODMAN: That is Julian Assange speaking on the day before the second anniversary of his stay at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Sarah Harrison is our guest in this global broadcast exclusive. She’s investigative editor of WikiLeaks, acting director of the newly formed Courage Foundation. She, in 2013, accompanied NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden on his flight from Hong Kong to Moscow and spent four months with him in Russia, before going to live in Berlin, Germany, though her home is in London. So, what gave you the—we’ve talked about the courage to do this, but also to sign up with WikiLeaks? You’re investigative editor. What does that mean? How did you end up working with WikiLeaks?

SARAH HARRISON: I had previously been working as an investigative journalist. WikiLeaks, for me, has not only that element in it of journalism publishing, but also the way in which it does it, with its—the concept we have of scientific journalism, I find very important and really appeals to me, that all of the source documents should be there. The concept of preserving history, collating full archives, making them as usable as possible so the public have access to them, I really feel that it allows the public an ability to engage with their own history. And we’ve actually seen that a number of the largest stories that have come out of our publications are because of people finding them themselves, or people who are involved in maybe a court case, then they have some more evidence for their court case, they’re able to try and get justice. And so, for me, this is a very important ethic that is very dear to WikiLeaks’s heart that few others do have.

AMY GOODMAN: How did your parents raise you?

SARAH HARRISON: They raised me to think for myself, question everything and do what I thought was right.

AMY GOODMAN: Have they visited you here in Germany?

SARAH HARRISON: They have. And they would probably agree that I am living how I was brought up.

AMY GOODMAN: So, here you are in Berlin, and you’re also running the Courage Foundation. Julian Assange is confined to the Ecuadorean Embassy.

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about how you’re able to do the work you’ve done. What have you done since he’s been in jail, and you can’t go home? I mean, not in jail, but he’s been in the embassy.

SARAH HARRISON: He’s been confined. Well, we can still work. Obviously, much of our work takes place online, so we’re still able to—I’m still able to do that work, and then, on top of that, have been involved in the setting up of the Courage Foundation. So I’ve been kept very busy here in Berlin.

AMY GOODMAN: And in terms of releasing information, can you talk about what WikiLeaks has released?

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah, well, we’ve still been releasing information. We have released the Syria Files, which are emails from some sections of the Syrian government, since he’s been confined. We carried on releasing the GI Files, which are emails from global intelligence agency Stratfor which showed spying on Bhopal activists. We’ve released policy documents, chapters of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which is a secret agreement that’s taking place covering a lot of the world’s countries in trade, and their IP chapters, which talk about very high levels of data sharing, environment chapters that, despite the rhetoric, they’re doing very little to actually combat environmental protections—or, to keep environmental protections. Our most recent release was of the Trade in Services Agreement, the financial annex of that, which again is another secret trade that’s taking place which affects over 60 percent of the world’s trade in services.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about how WikiLeaks handles documents, like the Iraq War Logs and—

SARAH HARRISON: How we handle them? We will do our own assessment. We get them ready for publication. We do our own journalism on them and write our own stories. But we also make large international collaborations. Cablegate, for example, we had 80 media organizations around the world that we were giving access to these documents to.

AMY GOODMAN: These were the State Department cables over decades.

SARAH HARRISON: Yes. And, of course, when it comes to large international publications like that, you do need local partners to be able to give the expertise and the full understanding of what’s going on in those regions, and, of course, to publish in the language of those countries for the people that it’s affecting. So, we put—we try to put together as large a media coordination group as possible for each publication.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the situation Julian Assange faces right now? It seems the climate is changing a bit in Britain, people saying, for example, “Why are they spending millions of pounds to keep him confined, when he has not even been indicted?” Not that an indictment means that you’re guilty, but that the Swedish government has not indicted him on charges of sexual mistreatment but has simply leveled allegations.

SARAH HARRISON: Yeah, I mean, it’s very interesting. Here is a man—there are obvious threats from the United States. There is a secret grand jury taking place trying to indict him and other members of WikiLeaks.

AMY GOODMAN: How do you know this?

SARAH HARRISON: There were documents that came out—I mean, there have been some public statements by government officials. But then there were also documents that came out in the Chelsea Manning trial, the alleged WikiLeaks source that was just sentenced to 35 years in prison. And they show categorically that this secret grand jury is taking place. So there is an obvious U.S. threat. There have been politicians talking about his—calling for his assassination. So his asylum is against the United States threat; that is at what Ecuador is protecting him.

Since the beginning of the Swedish allegations, Julian and now, since he’s been under their protection, the Ecuadorean government have been asking for Sweden to come and question him at the embassy. Of course, he would like nothing more than to clear his name and for this case to be ended, but the Swedes, despite the fact that it’s a regular legal practice, refuse to come and do so. The problem with if he were to be extradited to Sweden is that they have—the prosecutor there has petitioned for him to be put straight into solitary confinement. And then, regardless with what was happening with the U.S. case, he would not have the ability to take asylum. So he really needed to take that protection from the U.S. whilst it was still an available avenue for him.

AMY GOODMAN: And for those who say he could have been as easily extradited from London as from Sweden?

SARAH HARRISON: His asylum is not really a comment on that. It’s more a comment on his own situation and his ability to take asylum. Because he would be put straight into prison within Sweden into solitary confinement, he would be unable—even if the U.S. put in an extradition order, he would be unable to take asylum from jail there. So it really was a last moment for him to be able to take up this legal right.

AMY GOODMAN: And what is WikiLeaks concerned about him coming to the United States? What would be the charges he would face here—in the United States?

SARAH HARRISON: They’re trying to indict him for a number of charges, it seems like. It’s difficult to understand the exact parameters, because it is a secret grand jury and they’re letting as little out as possible. But it seems they’re trying to indict him for his publishing actions. They would like to work up an espionage charge against him. But, yes, it’s difficult to tell exactly. But a secret grand jury is there trying to indict him, and that only happens when it’s serious allegations.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve said you’ve set up the Courage Foundation to protect, help defend Ed Snowden and future Ed Snowdens. What should future Ed Snowdens do?

SARAH HARRISON: I think that it is important for them to understand that there are people that will support them. I think they should reach out to organizations like the Courage Foundation that can help them—ideally pre-emptively. It would be better if we didn’t have to save someone with their face all over the front pages of every newspaper in the world. And I think that—I think it’s important that they understand that there is a public desire for the truth and that they will hopefully be seen as heroes.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Sarah Harrison, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Sarah Harrison is the investigative editor of WikiLeaks, acting director of the newly formed Courage Foundation. Last year, she accompanied NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden on his flight from Hong Kong to Moscow and spent four months with him in Russia.

If you’d like a copy of today’s broadcast, you can go to our website at democracynow.org. We have job openings at Democracy Now! You can apply for administrative director or Linux systems administrator. We also have fall internships. Go to democracynow.org/jobs for more information.

Media Options