Topics

Guests

- Dave Shoresmember of UAW Local 696 and a GM employee of 20 years.

- Norman Sinclaireditor of The Detroit News.

- Anne-Marie Zenimera Teamster who works with distribution of the Detroit Sunday Journal.

United Auto Workers employed by General Motors in Dayton, Ohio, continue to strike, despite the efforts of negotiators. The strike began three weeks ago over the issue of outsourcing. One hundred fifty thousand GM workers at more than 20 GM plants throughout North America are participating in the strike. Dave Shores, a member of UAW Local 696 and a GM employee of 20 years, says that present and future jobs lie at the heart of the issue. Current workers are bogged down with overtime, and as a result, injuries on the job are rising. Meanwhile, outsourcing to other companies is a constant threat. While worker support for the strike is high, it is starting to take a toll on their families. Almost no politicians have acknowledged the strike in their election campaigns, and the striking families say they do not expect to receive their support.

In Michigan, the Detroit newspaper strikes move into their ninth month. With the aid of replacement workers, The Detroit News and Detroit Free Press continue to be published. Strikers, meanwhile, have begun publishing their own paper, the Detroit Sunday Journal. Norman Sinclair, the journal’s editor, says that job security and wages are underlying issues in the strike. Anne-Marie Zenimer, a Teamster who works with distribution of the paper to its 300,000 subscribers, says that the community and local politicians have been very supportive. However, media coverage of the strike has been weak, and so far no presidential hopefuls have stopped along their campaign trails to address them, although Clinton offered a “thumbs up” from his motorcade.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: And welcome back to Democracy Now!, Pacifica Radio’s national daily grassroots election show. I’m Amy Goodman.

Negotiators wrapped up 40 hours of nonstop talks early today, as a crippling strike by General Motors Corporation brake workers entered its third week. In Dayton, Ohio, 2,700 United Auto Worker members who work for General Motors have been on strikes for that amount of time, and they are protesting the issue of outsourcing, contracting out for parts. Talks between the UAW and GM will probably resume today, and the strike has idled about 150,000 GM workers at more than 20 GM plants in the U.S. and Mexico and Canada, resulting in projected loss production of about 93,000 automobiles.

We got a hold of Dave Shores, who is a member of UAW Local 696. He says the issue is jobs.

DAVE SHORES: We need jobs for our kids and our kids’ kids.

AMY GOODMAN: What about issues like overtime and outsourcing?

DAVE SHORES: OK. The overtime right now is unreal. We’ve got people working 10-, 12-hour days, some 16-hour days, six and seven days a week. We feel that if we can get more jobs in there, or more people in there, we can reduce some of the amount of the overtime. The effects of the overtime, you know, being in a repetitious job, is causing a lot of arm and hand injuries from repetitive motion. And so, by lightening the load on the overtime, we can get rid of some of those injuries.

AMY GOODMAN: We hear in the media a lot about outsourcing. Can you explain what that is?

DAVE SHORES: Outsourcing, there is an agreement between GM and the UAW that if there’s a supplier that puts a bid on a job and can do it cheaper than we can, we have 150 days to come up with an alternative method and try to get that cost down, OK? And if we can reach below that cost, if we can hit that target, we can keep the job. OK? Now, if we don’t hit that target, then the jobs are sent out.

AMY GOODMAN: And where are they sent to?

DAVE SHORES: Whoever bids on them.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, what do you want to happen?

DAVE SHORES: I’d like to keep the jobs in there, if we’re competitive with that job. You know, GM is a good place to work. It’s good money, good benefits. And the jobs out there, there’s not jobs. There’s not any jobs out in the world like GM anymore. We’d like to keep that.

AMY GOODMAN: What kind of attention have you been getting from politicians? For example, have the presidential candidates made stops at your picket line?

DAVE SHORES: No, no presidential candidates have stopped yet. Don’t really expect any right now.

AMY GOODMAN: What about presidential candidate Robert Dole? Wasn’t he in town?

DAVE SHORES: He was not in Dayton. He stopped up in Marysville at the Honda plant. But I just — I know that he was there, but I have no idea what he said or anything like that.

AMY GOODMAN: So, there was no — there was no strike at the Honda plant.

DAVE SHORES: No

AMY GOODMAN: How did you take this?

DAVE SHORES: Well, the Honda plant, as far as I know, is non-union.

AMY GOODMAN: Are there any politicians out there who have expressed support for your strike?

DAVE SHORES: No politicians, per se. We did to receive a letter from Jesse Jackson.

AMY GOODMAN: What did he say?

DAVE SHORES: That he was just congratulating the local on their courage.

AMY GOODMAN: What kind of support have you been getting from other workers?

DAVE SHORES: That’s unreal. We’ve had several locals come in. We had a local last week from Flint, Michigan. They brought — there was about 50 or 60 people. They come in, join our picketers on the picket line. We had a local from Sandusky. Today, we had three members from the Ford plant in Milan, Michigan, come down. They had a letter that had been blown up and signed by everybody in the plant and is now hanging in the window, where the negotiations are being held at.

AMY GOODMAN: I hear your child in the background. What kind of impact has the strike had on your family?

DAVE SHORES: It’s rough. I’m gone a lot more now, you know, helping out at the union hall and wherever they need me at. And it’s tough. You know, I have a wife that’s disabled, and I have two stepdaughters, one being autistic. And I need to be home.

AMY GOODMAN: What would you like to see the president do, or the presidential candidates?

DAVE SHORES: As far as the strike’s concerned?

AMY GOODMAN: Mm-hmm.

DAVE SHORES: I’m really not worried about the politicians. I just — we want to get these things settled, and we want to get back to work. You know, we build the best brake in the world, and we want to keep going.

AMY GOODMAN: I was wondering if your wife is around, if she might be able to come to the phone.

DAVE SHORES: Yes, she’s right here. Her name is Jill.

JILL SHORES: Hello.

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. Is this Jill Shores?

JILL SHORES: This is.

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. This is Amy Goodman from Democracy Now!, which is a national election radio show.

JILL SHORES: How are you?

AMY GOODMAN: Good. I was wondering how the strike is affecting you and your daughters.

JILL SHORES: Very nerve-wracking for myself. Try to keep my daughters in as normal situation as possible. My youngest one is autistic, so we kind of have a different daily living arrangement than most normal families do. So, that, in itself, is very stressful. And with my husband being on strike right now, it’s very stressful, very emotional. And I’m probably the most emotional person in the world. I kind of wear my heart on my shoulder. And when my husband looks at me, he knows if I’m scared, worried, angry, upset or whatever. So, we talk a lot. We hold each other a lot. We tell each other we love each other more than we ever have. And we just try to take hour by hour, minute by minute, if that’s what it takes to get through it. So…

AMY GOODMAN: How about sources of support outside your family? For example, do you in any way look to politicians to solve the problems here? Do you look to the president or to the presidential candidates to make any comments?

JILL SHORES: That’s the furthest thing from my mind right now. My support is within the local union here in Dayton, Ohio. Its president and the members, my husband has very good faith in them. And that’s enough for me. So, I look to the hearts of all of those to sit down and come to some kind of an agreement that will not only benefit my family, but the whole world, if so need be, for our future.

AMY GOODMAN: I appreciate you coming to the phone. Could you put your husband back on for a minute?

JILL SHORES: Yes, I sure will.

AMY GOODMAN: Thanks a lot.

DAVE SHORES: Hello.

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. Dave Shores, I was just wondering — earlier, you said that GM is the best job in the world. Why do you say that?

DAVE SHORES: I’m not saying it’s the best job in the world. It’s a very hard job, OK, but the money and the benefits are what’s great. You just — you don’t find jobs out there anymore that has the money and the benefits that GM does.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it’s going to stay that way?

DAVE SHORES: I’d like to see it stay that way, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: How —

DAVE SHORES: I understand the company’s position, where they have to get competitive. And, you know, like other companies before GM, you know, where they’ve — they always reduce costs, you know, but they stay competitive at the workers’ cost.

AMY GOODMAN: How long have you been at the plant?

DAVE SHORES: Twenty years.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you do?

DAVE SHORES: I’m an assembler.

AMY GOODMAN: Which means?

DAVE SHORES: I help assemble the brake assemblies.

AMY GOODMAN: And how much money do you make before the strike and now?

DAVE SHORES: Well, I was making General Motor wages before the strike, and now we get the strike benefit of $150 a week.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think you can hold out long?

DAVE SHORES: I have a side business that should be starting up next month. It’s going to be a struggle.

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Shores, thanks for joining us.

DAVE SHORES: Thank you very much.

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Shores is one of 2,700 United Auto Workers who work for General Motors, are in the third week of their strike in Ohio, one of today’s primary states. The strike at the two Dayton parts plants has idled about 150,000 GM workers in the United States, Mexico and Canada.

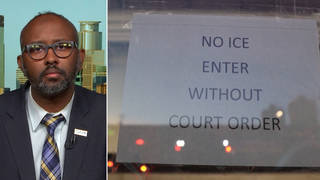

Another of the states where voters are going to the polls today is Michigan. There, the Detroit newspaper strike has been going on since last summer with no end in sight. All the unions have stuck it out, except for the Newspaper Guild, half of whose members have gone back to work at The Detroit News or the Detroit Free Press. The two papers have continued to publish with replacement workers. Strikers have put out an alternative paper of their own, the Detroit Sunday Journal, which has a circulation of 300,000.

We’re joined now by two people who are on strike. Norman Sinclair is the editor of the Detroit Sunday Journal. And we’re also joined by Anne-Marie Zenimer, who is a Teamster who works with distribution of the paper.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now!

ANNE-MARIE ZENIMER: Thank you. Hello.

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. Why don’t we begin with Norman Sinclair? Can you tell us what is at issue here in this strike?

NORMAN SINCLAIR: Well, basically, Amy, it’s job security. It’s taking care of people who spent 20 to 30 years helping these newspapers get into a very profitable position. It’s folks who have lived for the last three years without a wage increase, accepting a freeze three years ago, giving back to the companies and having very little to show for it three years later.

AMY GOODMAN: What sparked the strike?

NORMAN SINCLAIR: Well, you know, our contract expired in April, and all six unions were working without a contract while negotiating for a new one. And on July 13th, there was a strike deadline set, and the company decided that they did not want to go along with the arrangement of continuing to negotiate. On the day of the strike, the mayor of Detroit, Dennis Archer, tried to intervene. The six unions agreed to continue negotiating and continued to work under the old contracts, and the company said no and foreclosed on the contracts.

AMY GOODMAN: Anne-Marie Zenimer, you’re a Teamster who works with distributing the alternative to the papers that are on strike, the Detroit Sunday Journal. How do you get this paper out to 300,000 people? How does it work?

ANNE-MARIE ZENIMER: Oh, well, we have actually started out with — the same way that the News and the Free Press is delivered. We delivered to stores and dealers, and then we also did what we called random home delivery to introduce our paper to the people. In the last four weeks, we have also started up mail subscription, actually mailing the copies of the paper to people.

AMY GOODMAN: What kind of support are you getting? Are you getting any from local politicians, for example? What about community groups?

ANNE-MARIE ZENIMER: We’re getting enormous support from politicians, from — the community has been tremendous in their support. As a matter of fact, in the last three weeks, the community theirselves, including a large sector of the religion community, have been sponsoring rallies in front of the News building to show their support. We had 44 women arrested last week for civil disobedience, and the prior week to that, we had, I believe, over 20 religious leaders also demonstrate the same sort of support.

AMY GOODMAN: Anne-Marie Zenimer, you are a Teamster, and I wanted to ask how much of the fact that this strike has gone on for so many months has to do with a presidential campaign of your own, which is in the Teamsters, between Jimmy Hoffa Jr. and the current president, Carey, the fact that this really, your area, is Jimmy Hoffa Jr.’s stronghold, and that if this were settled, it would make Ron Carey look good.

ANNE-MARIE ZENIMER: Well, actually, after eight months, this strike — I know you referred to me as a Teamster, but in this eight-month-old strike, there are six other unions. And I believe myself, amongst with all these other unions, we don’t refer to ourselves as Guild members anymore or Teamsters or CWA. We’ve become so united that I believe the issues between Carey and Hoffa are our least concern right now. Our main concern is reaching the public and the community and letting them know what’s going on here has nothing to do with unions, as in Hoffa and Carey. It has what we’re — our concern, our workers’ concerned —

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you another question. During the course of the strike, there was a change in leadership at the AFL-CIO with the election of Sweeney. Has that had any impact on the strike?

ANNE-MARIE ZENIMER: They have showed tremendous support. As a matter of fact, at the convention in Miami, which was approximately three weeks ago, we were invited. Six rank-and-file members were invited to the actual conference, and we were also invited into the executive committee meeting, where the support was tremendous, not only emotionally, but financially. And they’ve vowed to stand by our side and see this through.

AMY GOODMAN: Norman Sinclair, I wanted to ask you about coverage of your strike. I mean, after all, it is a newspaper strike. How are other newspapers around the country covering it? I mean, we’re looking at unions at The New York Times, at The Wall Street Journal, at The Washington Post.

NORMAN SINCLAIR: I think they do a lukewarm job of covering it, only because it’s a curiosity. I mean, to hear that worker from Dayton, they’ve been on strike for three weeks. We’re going into our ninth month, and The New York Times, their local bureau, wrote a story back in October that the strike was over, which is basically the propaganda that the company has put out. The problem we have is that both newspapers are publishing. They look the same, but when you pick them up, you can see that there’s hardly anything in it. We broke the biggest story that they’ve had in Michigan for some time now, on the FBI’s attempt to derail organized crime in the state. We had the story back on December 10th. It broke here last week, with both newspapers running screaming headlines as if World War III had been declared.

AMY GOODMAN: Would you call Detroit a union town?

NORMAN SINCLAIR: Absolutely. But what you have here are two almost foreign companies, Gannett and Knight Ridder, coming to town with a plan to try to wipe these newspaper unions out. And because of the electronic capability today, they can produce the product, the newspaper, and they have been able to convince a lot of the media that come to town, you know, “Look at the papers. See? We’re producing a paper. The strike is over. Those folks out there are doing a futile effort at continuing the strike.”

AMY GOODMAN: Have any of the presidential candidates stopped by, showed their support?

NORMAN SINCLAIR: Well, the closest we got to any of that was Bill Clinton. He was in town a couple of weeks ago to dedicate a public building in a suburb south of Detroit, Taylor. And he was giving a speech several blocks away from the Detroit News building. His motorcade at the dedication, one of our Guild officers managed to get into the reception line with her sign, her picket sign, shook hands with the president and invited them to the picket line. He demurred coming to the picket line, but something must have happened after he gave his speech downtown, because his motorcade, instead of leaving the hall and going straight to the expressway, there’s an exit right — an entrance ramp right there. Instead of getting on the expressway, they came up about four blocks from the hall where he spoke, and passed within a half a block of The Detroit News, where all the picketers could come over to the corner and wave at him, and he gave them the “thumbs up” sign.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much, Norman Sinclair, Detroit Sunday Journal editor, and Anne-Marie Zenimer, Teamster who works with distribution of the alternative paper as the Detroit newspaper strike continues into its ninth month.

You’re listening to Democracy Now! And as we look at these labor struggles in the context of the presidential primaries, we decided to go back in history and look at how presidents and candidates deal with strikes, have dealt with them in the past. A number of presidents and candidates made their reputation on labor issues by breaking strikes — most recently, of course, Ronald Reagan, when he fired 11,000 striking air traffic controllers. A century before, President Grover Cleveland worked with his attorney general to send in federal troops to end the Pullman railway car strike, a strike led by future Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs. In 1919, then-Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge broke the Boston police strike. His statement that there was no right to strike against the public health and safety anywhere, anytime, catapulted him into the national spotlight and propelled him to the presidency in 1924. And at the end of World War II, Harry Truman threatened to use federal troops to end strikes in defense-related industries.

On the other hand, Socialist Party candidate Debs led strikes, and Norman Thomas, six-time Socialist Party presidential candidate from 1928 to '48, walked numerous picket lines. In recent years, Jesse Jackson and Tom Harkin have walked with picketing strikers, but have failed in their quest for the Democratic presidential nomination. And while he has said he would have supported the striking Boeing workers, Pat Buchanan has not yet appeared on any picket lines. Interestingly, it's the third-party candidates, like Debs, who have been most likely to appear on picket lines. Norman Thomas walked numerous lines. And by the way, we will continue covering these strikes. We’ll continue covering them in the days to come. You’re listening to Democracy Now! Up Next, we go to Chicago.

Media Options