Topics

Guests

- Rebecca Solnitwriter, historian and activist. Her latest book is called A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster.

We speak with author, historian and activist Rebecca Solnit about her latest book that examines Hurricane Katrina and other disasters. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster chronicles both the crimes of the vigilantes and the powerful during Katrina, as well as the numerous instances of altruism, generosity and courage displayed by the vast majority of people who lived through this catastrophe. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We continue on this fourth anniversary special, yes, four years after the storm. Anjali?

ANJALI KAMAT: It’s widely acknowledged that an estimated 1,400 people in New Orleans died in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. An underreported part of that story is the killings of at least eleven African American men in the days after the storm. They were shot by a group of white vigilantes in the predominantly white New Orleans neighborhood of Algiers Point.

Local police have never conducted an investigation into these deaths, but after an explosive Nation magazine cover story by ProPublica reporter A.C. Thompson last December, the FBI initiated a probe into the Algiers Point shootings. Federal agents are now investigating the possible role of the New Orleans Police Department in the deaths of one of the men, Henry Glover, whose burnt remains were discovered in a Mississippi River levee not far from a local police station.

We’ll be joined in a few moments by writer Rebecca Solnit, who urged journalist A.C. Thompson to investigate this story. But first I want to turn to excerpts from a video produced by the Nation Institute and Hidden Driver. It’s narrated by A.C. Thompson and features interviews with some of the victims of the vigilante violence.

A.C. THOMPSON: At the ferry terminal in Algiers Point, the National Guard established an evacuation zone and began busing flood victims to Houston. On September 1st, 2005, Donnell Herrington left his home and began walking toward the ferry terminal with his cousin, Marcel Alexander, and a friend, Chris Collins. To get to the evacuation zone, the trio had to walk through Algiers Point.

DONNELL HERRINGTON: You know, I was talking to my cousin and our friend, and I was telling them that, yeah, we’re finally about to get out of here. You know, I was talking. I was talking, because my cousin was on the side of me, on the right side, and I looked down at my arms and everything, and — because, you know, some of the shots hit me in my arm, my chest, my neck, my stomach. And, you know, I just saw blood everywhere.

MARCEL ALEXANDER: As I’m trying to pick him up, they shot us again, so I fell. And Donnell’s trying to get up, and we all were trying. We’re panicking now.

DONNELL HERRINGTON: And he was like hollering, like, “You OK? You alright?” And he was, you know — like I said, he was pretty hysterical, man. And when I — you know, when I saw the guy, when I actually recognized the guy with the shotgun, you know, it was like he was reloading or something.

MARCEL ALEXANDER: As I’m trying to pick him up, they coming towards us with the gun. It’s like probably like — at that time, it’s like probably two or three of them.

DONNELL HERRINGTON: And so, now I’m trying to get out of this guy — trying to get away from him, you know?

MARCEL ALEXANDER: Two of them coming my way and one of them coming at Donnell with — [inaudible] Donnell. And I’m running, me and Chris, running, running. They was like, “We’re gonna get you! We’re gonna get you, nigger!”

DONNELL HERRINGTON: I ran up into the corner. And they had these two guys in a car. They had these two white men in a car, a older white guy and another — you know, a younger white guy. And they had their shirts off. I can remember, you know? And they were like in a small pickup truck.

MARCEL ALEXANDER: We know y’all — what y’all was doing. We saw y’all.

A.C. THOMPSON: Marcel goes on to say the vigilantes thought he was a looter.

DONNELL HERRINGTON: And, you know, I’m asking these guys, I’m like, “Help! You know, help me! You know what I mean?” And the guys was like — I can remember him telling me, “We can’t help you, you know? Get out of here.” You know what I’m saying? And one of the guys, one of them — I can remember one of them calling me a nigger. You know, “Get out of here, nigger! We can’t help you. We’re liable to shoot you ourselves.” That was the last thing I heard him say.

A.C. THOMPSON: Eventually, Herrington got help. A black neighbor drove him to the hospital, where doctors pulled seven lead pellets out of his neck and repaired a large hole in his jugular vein, saving him from death.

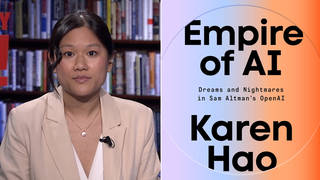

ANJALI KAMAT: We’re joined now from Santa Fe, New Mexico by author, historian and activist Rebecca Solnit. Her latest book examines Katrina and other disasters; it’s called A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. It chronicles both the crimes of the vigilantes and the powerful during Katrina, as well as the numerous instances of altruism, generosity and courage displayed by the vast majority of people who lived through this catastrophe.

Rebecca Solnit, welcome to Democracy Now! Why don’t you start by talking about how you discovered this story and the process you went through before you got A.C. Thompson to investigate this? You write about how many of the mainstream media journalists you spoke to didn’t believe this story.

REBECCA SOLNIT: You know, the thing that still amazes me two-and-a-half years later is that the pieces of this story were all over town. If you wanted to know that this — these crimes had happened, you would know it. It was pretty clear the mainstream media didn’t want to know. Nobody was really looking at it. I had talked to volunteers who worked at the Algiers Common Ground clinic. They told me that vigilantes were confessing to them about the murders, about several murders. I talked to Malik Rahim, who I know was on this show right as all this was unfolding. He was talking about as many as eighteen men being murdered in that part of New Orleans Parish. I had seen Donnell Herrington, who you just showed, on Spike Lee’s documentary. I’d seen another documentary in which the vigilantes confessed on camera. I’d seen a lot of other pieces. It was really clear that there was a story here.

And I couldn’t find anyone to take it, until I talked to A.C., who is a friend of a lot of friends of mine. We were in the same social circles in San Francisco. And he eventually picked it up, with the support of The Nation magazine, as well as ProPublica. And it took him a long time to move forward with that. But he’s the one who really brought a lot more of the details to light, tracked down Donnell, talked directly to the perpetrators, and put it together. But, you know, a lot of the basic information was out there, if that’s how you were willing to think about Katrina. But that’s now how a lot of people were ready to think about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Rebecca, your latest piece, “Four Years On, Katrina Remains Cursed by Rumor, Cliché, Lies and Racism.” Talk about Katrina. Talk about New Orleans four years later.

REBECCA SOLNIT: You know, I think one of the important things to keep in mind is that the great majority of people behaved really well, that I was trying to write the counter-story to the story that most people heard in the beginning, which was about large groups of marauding hordes reverting to barbarism and savagery and violence and whatever. And I went to New Orleans to look at what really happened, which was an enormous amount of volunteerism, resourcefulness, altruism, generosity, heroism, on the part of the people who were stranded, on the part of the people who came in as volunteers and rescuers.

And the question for me is, so why did the minority misbehave? And in this case, I’m not talking about the minority the media were willing to target, which was supposed to be sort of the black underclass; the minority who were public officials and the vigilantes. They assumed, falsely, that because the public, in general, was behaving barbarically, they needed barbaric means to repress that public. Vigilante murders are part of a larger picture that includes the sheriff of Gretna and his henchmen turning people back from evacuating the flooded city at gunpoint, incidents of police violence, but also the mayor, the governor, FEMA and a lot of other people treating the city of New Orleans as though it was full of criminals, rather than victims, and essentially turning it into a prison city in which people were stranded and desperate. And the hospital evacuations, for example, could have happened a lot faster. It could have all happened a lot faster, if people had thought about these things differently.

ANJALI KAMAT: Rebecca Solnit, in your book, you talk about several disasters, and you mention how, even in this worst of times, in the midst of disasters and in times like this, the best instincts of people tend to come out. Talk about the sense of community that was built. You know, we’re focused on the deaths, on the vigilante shootings, but people also helped each other, ordinary people. How did they come together at this moment?

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yes, in most disasters, people do behave altruistically, resourcefully. They improvise communities. And they often find in that a real sense of joy. You see that in the 1906 earthquake. You saw that in 9/11. You see that in Katrina. And essentially, that the normal roles and boundaries that confine people are removed, and it’s absolutely necessary that people connect with each other, that they make strong decisions, that they take care of each other. And that’s what they do.

One of the tragedies of New Orleans is that, because of the stereotypes that turn into rumors, that turn into media reports, people believed that ordinary human beings were savages and were behaving barbarically. The truth of the matter is, even inside the Convention Center, even in the worst places, people were taking care of each other. People were improvising all kinds of communities in the school rooms and other places where they took refuge. And New Orleans, since then, has had hundreds of thousands of volunteers come in to work with the people of New Orleans. And for me, that’s the big story. And demographically, it’s much, much bigger. You’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people. And the minority who behaved terribly matter, but it’s important to keep the perspective that this is not how most people behave. This is indeed a minority.

AMY GOODMAN: You put this in a very big context, dealing with disasters, from the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco to the 1917 explosion that tore up Halifax, Nova Scotia, to the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, to Katrina. Talk, in those cases, about the similarities you saw, the individual heroes and heroines and the institutional crimes, the institutional lack of response.

REBECCA SOLNIT: You know, a lot of my work has been based on the field of disaster sociology, which emerged after the World War II, when the US government decided it wanted to know how human beings would behave in the aftermath of an all-out nuclear war. The assumption, as it often is, is that we would become childlike and sheepish and panic and be helpless, or that we’d become sort of venal and savage and barbaric. And the disaster scholars started to look at this and eventually dismantled almost every stereotype we have and found that people are actually, as I’ve been saying, resourceful, altruistic, brave, innovative and often oddly joyful, because a lot of the alienation and isolation of everyday life is removed. And, you know, you saw that in the 1906 earthquake, which I studied a lot for the centennial a few years ago, that people created these community kitchens, that they were extremely resourceful and helpful. And you see that all through. You see that in Mexico City. You saw that in 9/11.

What you also see is that because the authorities think that we’re monsters, they themselves panic and become the monsters in disaster. Some of the sociologists I worked with — Lee Clarke and Caron Chess — call this “elite panic,” and that’s the panic that matters in disasters, the sense that things are out of control; we have to get them back in control, whether that means shooting civilians suspected of stealing things, whether that means focusing on control and weapons as a response, rather than on help and support or just letting people do what they already are doing magnificently. And so, it really upends not only the sense of what happens in disaster, in these extreme moments, but I think it upends our sense of human nature, who most of us are and who we want to be. There’s enormous possibility in disaster to see how much people want to be members of a stronger society, to be better connected, to have meaningful work, how much everyday life prevents that.

AMY GOODMAN: Rebecca, we’re going to have to leave it there. Rebecca Solnit, author of A Paradise Built in Hell.

Media Options