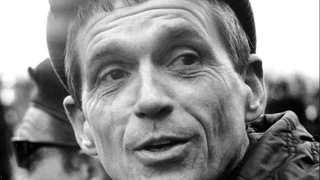

More than 800 people packed into the Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York Friday for the funeral of Daniel Berrigan, the legendary antiwar priest, poet and activist. He died on April 30 at the age of 94. Today would have been his 95th birthday. Dan and his brother, the late Phil Berrigan, made international headlines in 1968 when they and seven other Catholic antiwar activists burned draft cards in Catonsville, Maryland, to protest the Vietnam War. Prior to the funeral, hundreds took part in a two-hour procession beginning at Mary House, a Catholic Worker house in the East Village. Democracy Now!’s Mike Burke was there and spoke to participants including singer Dar Williams, the Rev. John Dear, Dan’s niece Frida Berrigan, Kathy Kelly and John Schuchardt, who was arrested with Dan in 1980 when they broke into the GE nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, launching the Plowshares Movement.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from Portland, Oregon. More than 800 people, though, packed into the Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York Friday for the funeral of Dan Berrigan, the legendary antiwar priest, poet and activist. He died April 30th at the age of 94. Dan and his brother, the late Phil Berrigan, made international headlines in 1968 when they and six other Catholic antiwar activists burned draft cards in Catonsville, Maryland, to protest the Vietnam War. Prior to the funeral, hundreds took part in a two-hour procession beginning at Mary House, a Catholic Worker house in the East Village in New York. Democracy Now!’s Mike Burke was there and spoke to participants.

ANNA BROWN: I believe we’re going to start our march now, and so I would think that we would want to create some space here, maybe walk together arm in arm, linked, again, with great energy, with chanting, with song, because this is a celebration of Dan’s life and of life itself.

PROCESSIONISTS: [singing] Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

MIKE BURKE: Can you begin by telling us your name and why you’re here today?

DAR WILLIAMS: I’m Dar Williams. And I’m here because I wrote a song that had to do with the Catonsville Nine, and then everything changed. As soon as I wrote that song, I met all of the people who were part of that song. And here I am, you know, 15 years later.

MIKE BURKE: Do you think you could sing a verse of that song right now?

DAR WILLIAMS: Sure. It goes:

[singing] God of the poor man this is how the day began

Eight co-defendants, I, Daniel Berrigan

And only a layman’s batch of napalm

We pulled the draft files out

We burned them in the parking lot

Better the files than the bodies of children

I had no right but for the love of you

I had no right but for the love of you

So it’s like a prayer, saying to God, you know, “They tell me I had no right to do this, and I had no right to do this but for the love of God.”

REV. JOHN DEAR: I’m John Dear, and walking here along the streets of Manhattan to remember Daniel Berrigan. We’re just passing the Catholic Worker house where Dorothy Day lived and worked, Dan’s great friend, who’s going to soon be canonized. And I’m here with all our friends on the way to the funeral to commemorate Dan, one of the greatest peacemakers of our times, my great friend, who called us to take to the streets and to say no to war and injustice and nuclear weapons, and to put nonviolence into action.

MIKE BURKE: And how did Father Berrigan influence both the peace movement as well as the Catholic Church?

REV. JOHN DEAR: Daniel Berrigan inspired millions upon millions of people after the Catonsville Nine action to—the symbolic act of the Catonsville Nine, especially him, but he and his brother as priests. This has never happened before, and it was so shocking. But it led to millions of people taking to the streets and inspired the peace movement. And you could argue—there were 300 draft board raids—it helped end the draft and helped end the war.

But then he changed, in the process, the church, Catholic Church in the United States—actually all the Christian churches—and the church around the world. We never had a priest so publicly actively against war. Now it’s normal. And a priest going to jail and prison for peace, now that happens all the time. But he broke the new ground and, in effect, helped get rid of the “just war” theory and return us all back to the peacemaking life of Jesus, which was the point of the church. So, he’s not only a great saint and a great prophet, he’s actually one of the great revolutionaries who’s inspired the movement and changed the church. It’s quite an accomplishment.

PROCESSIONISTS: [singing] We ain’t gonna study war no more,

We ain’t gonna pay for war no more.

MIKE BURKE: Can you begin by telling us your name and how you knew Father Berrigan.

FRIDA BERRIGAN: My name is Frida Berrigan. I’m Dan Berrigan’s niece. And yeah, it’s raining, and we’re on Houston Street, and we’re remembering him and all the times he stood in the rain, and there weren’t 300 people, and there wasn’t a band, and there wasn’t all of this joy. And we’re reminded that like this is—this is where it happens, right? Doesn’t happen in the classroom. It doesn’t happen from the altar. It happens in the street. And it happens those places, too, but not without this.

TED GLICK: Hi, my name’s Ted Glick. I met Daniel Berrigan in 1970, when I was active in the antiwar movement of the Vietnam War, the draft resistance movement. I mainly got to know him in prison. We were both in prison in Danbury, Connecticut, for draft board raids, him for the Catonsville raid in 1968 and me for a draft board raid in 1970.

MIKE BURKE: Can you describe what happened at Catonsville and then describe the significance?

TED GLICK: Catonsville was where nine people went into a draft board, Catonsville outside of Baltimore. They took the 1-A files, the files of young men who were liable to be drafted and sent to Vietnam. They took them outside, and they put homemade napalm on them and burned them. That was the—there was one other small action before that in Baltimore in the fall of ’67. This one in May of ’68 was the one that got lots of attention, lots of publicity. And it started a movement, that I ended up getting involved with, of people who went into draft boards all over the country, as well as corporate offices, FBI offices a couple of times, and took direct action, nonviolent direct action, serious direct action, against war and injustice, particularly against the Vietnam War, of course, at that time. So the significance was that for the antiwar movement, it gave a real shot in the arm to that movement at that point in time. And it continued to do so with the growing number of these types of actions that just continued to multiply over the next three, four years.

ANNA BROWN: My name is Anna Brown. I’m a member of the Kairos Community. I’m here primarily today, first of all, because I loved Dan very much—I’ve been a member in community with him for 25 years—and because he was such a great force of love in this world. In the Catonsville Nine, he talks about the creation of a new order of gentleness, of kindness, of loving community. And we just don’t do that. We just don’t do that. And I think that’s why there’s been this incredible response to his death, because, really, he’s all about life. And in a time where we’re watching children drown in the Aegean Sea and climate change is barreling down upon us, though we remain in denial, and we’re fighting war after war, someone who speaks about love is someone who we need to listen to. But not only spoke about it, acted on it, did it, so consistently. I can tell you Dan was doing civil disobedience almost to the end of his life.

MIKE BURKE: Can you begin by telling us your name and how you knew Father Berrigan?

JOE COSGROVE: I’m Joe Cosgrove, and I’ve known Dan Berrigan for more than 35 years. Dan was my pastor, but I was in theology and law. Well, gee, what two better subjects than—to put to use for Dan Berrigan? So I was his lawyer then for over those 30 years and in all sorts of matters and issues that he—when he was arrested many times in New York and other matters and civil rights issues.

MIKE BURKE: Can you describe some of the more memorable cases that you represented Father Berrigan?

JOE COSGROVE: Well, you know, that, as I said last night at his wake service, Dan turned everything into liturgy. So, for me, I’m litigating, but for him, it was a sacrament. And to see that contrast. So, his statements and his testimony in court, every one of them were scriptural. I think, in particular, at the resentencing of the Plowshares Eight, which after this decades-long appeal process, when there were—the case was overturned, the conviction was overturned, then it was reinstated, but then the judge was removed. And then, finally, after 10 years, it seemed that there was an exhaustion in the legal system, and the resentencing was ordered, with a new judge. And because of my work in that system, I was doing most of the work at the resentencing. And Dan’s statement to the court is—it’s one of the most profound things I’ve ever heard from a historical, from a legal and from a theological point of view. He combined all three. And it’s poetry. Dan’s a pot. It’s scriptural. He’s a scripture scholar. It’s liturgical. It’s beautiful. And that really, I think, is one of the crowning moments in—maybe in American legal history, to have that statement read in court, stated in court.

MIKE BURKE: Do you remember any of the lines from that statement?

JOE COSGROVE: He said, “If you think that putting me in jail will help end the war, then take me away.”

PROCESSIONISTS: [singing] I ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

MIKE BURKE: If you could begin by telling us your name?

ART LAFFIN: My name is Art Laffin, and I’m with the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker in Washington, D.C. And the sign that I’m holding, I hold every Monday morning at our Pentagon peace vigil, 7:00 to 8:00 a.m. The vigil has been going on since 1987. And—

MIKE BURKE: For our radio audience, what does the sign say?

ART LAFFIN: Well, the sign says, “No cause, however noble, justifies the taking of a single [human] life, much less millions.” It’s a quote from a talk that Dan gave on the ethic of resurrection. But it sums up—it sums up his unequivocal commitment to nonviolence, which is rooted in the scripture. His life was staked on the command “Thou shall not kill” and to love your enemies.

COLLEEN KELLY: My name is Colleen Kelly. And I don’t remember the first time I met Dan. I know it was somehow connected to Covenant House, when I worked at Covenant House years ago. But he made an enormous impression on my life in many, many ways. And I think one of the things that sticks out for me is my brother was killed on September 11th here in New York City, and in the shock of all that, within the first week, I went to go see Dan and just talk to him about—about this tragic, awful thing that like was so incomprehensible and impossible to understand. And I don’t—Dan was a poet, and I don’t really get poetry all that much, but—and I don’t know—you know, he was a wise man, and I can’t tell you a wise phrase that he told me that night. But I can tell you, like, his heart just came and enveloped my heart. And I knew at that moment—not at that moment. It was like—it was just Dan—having Dan’s backup and love and compassion, it made it very clear that the only way to respond to the violence that had happened was nonviolently and with justice. And it feels like Dan helped me understand that in ways I never thought I would concretely have to understand. And I was so glad that he was a part of my life prior to that, so that he—he was there in that really awful, awful, tragic moment.

MIKE BURKE: If you mind telling us your name, how you met Father Berrigan and why you’re here today?

JOHN BACH: My name is John Bach. I was a draft resister during the war in Vietnam. And I first met Dan in the dining hall of the federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut. And it was love at first sight.

MIKE BURKE: And what do you think is most important for people to know about Father Berrigan?

JOHN BACH: That freedom and liberation are things that you can declare for yourself. And when you do that, you never lose a step, and you help your community move forward into the light.

MIKE BURKE: And how long did you spend in jail?

JOHN BACH: I spent 35 months, just under three years. And I can say, because of Dan, because of what he taught me—most of the time I was not with the Berrigans—that it was three of the most formative, spiritual, educational and, in some ways, fun years of my life. I have no regrets whatsoever.

MIKE BURKE: Do you know of any other draft resisters who spent longer periods in jail than you?

JOHN BACH: There was only one.

MIKE BURKE: And what are your thoughts today as we march, you know, in the rainy streets of New York, as we head towards the church?

JOHN BACH: That there is a spirit working among us that strikes us free, as we work together on behalf of other people. And the best we could do at the end of our lives is to ask ourselves two questions: Were we well loved? And did we serve other people? And for Dan, there’s a rousing affirmative, unquestionably, about that.

KATHY BOYLAN: So, I’m Kathy Boylan. I’m a Catholic Worker from Washington, D.C. And I was 24 years old on May 17, 1968, turned on the radio, and—I don’t think it was WBAI, but I was in New York—and I heard the story of Catonsville. And I was already the mother of two little children; I had another baby on the way. And I describe myself as, standing up, a different person, one with a view of taking responsibility for trying to end the war in Vietnam. The day before, I didn’t think it was my responsibility. So that’s how—I first met him in the story on the radio of Catonsville, of the Catonsville Nine action.

But then I got to meet him. I was in the prison yard at Danbury in '72 with Dan when Phil was released from the—he got a six-year sentence, I believe, for Catonsville. So I was then—by then, from ’68 to ’72, I was already part of the community. Then I heard Dan say, in quoting the Isaiah scripture, “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, their spears into pruning hooks.” And he said, “Well, who are these ’they' who are going to do this beating swords, if not us?” And so that’s led me to swim to a Trident submarine and hammer on various implements of war. I’ve been arrested. I am so happy. I am so blessed. It was miraculous that I listened to that radio program on May 17, 1968. My whole life is different because of it.

PROCESSIONISTS: [singing] Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

Down by the riverside

Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

KATHY KELLY: My name is Kathy Kelly. I’m a co-coordinator of Voices for a Creative Nonviolence. And I’m here out of deepest respect and appreciation for Dan Berrigan and for the very wonderful community that has come together to remember his life and to be grateful.

MIKE BURKE: And what impact has Dan had on your life?

KATHY KELLY: You know, as a teenager, if I got on the express bus early, I could get downtown before starting work and go to St. Benet’s bookstore and read about Dan Berrigan. And since that time, he’s had a strong shaping effect. I was very impressed that in 1991, when a group of people from the United States assembled to go and kind of interpose ourselves between warring parties in Iraq, and people said what motivated them, over half the group had been motivated by Dan Berrigan’s words. And likewise in Afghanistan, young kids now know about his work and read his poems. And it’s pretty wonderful to hear that a whole group of mainly Pashto students stood up and cheered after a Hazara student read a poem by Dan Berrigan that moved him.

MIKE BURKE: Can you begin by telling us your name and how you knew Father Berrigan?

JOHN SCHUCHARDT: John Schuchardt from the House of Peace in Ipswich, and my wife Carrie. I met Dan about 40 years ago, exactly this time of year 40 years ago, at Mary House, where we began the walk this morning. And it has guided and influenced the following 40 years of my life in a major way. And my wife Carrie met Dan when she was 16 years old. And that, too, was a formative influence in her entire life. So that led to Jonah House and, ultimately, to nuclear resistance, and then forming a community of eight to go into the nuclear weapons factory at General Electric in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, September 9th, 1980.

MIKE BURKE: Can you go back to that day in 1980, and describe what you did and why you did it?

JOHN SCHUCHARDT: Well, we had been—Brandywine Peace Community had been vigiling at plant number nine, where there were 600 workers making the nuclear warhead, the Mark 12A first-strike nuclear warhead. And as we vigiled there—and I joined the vigil a number of times, came up from Jonah House and vigiled with Bob Smith and the Brandywine community—we realized that we could get into that plant. And if what we understood was true, that this was a crime, that this was the manufacture of genocidal nuclear weapons, each warhead 35 Hiroshimas—and there’s no such thing as a non-genocidal nuclear weapon, but these are, each one, 35 Hiroshimas—is it enough to stand outside and vigil?

And we decided it really wasn’t, that we could go in and stop production. We decided that we would enter with the workers at the peak of the morning workday. I think it was about 7:00 a.m. in the morning. And Carl, Father Carl Kabat, and Sister Anne Montgomery would talk to the guard there, distract that guard, while the rest of us went into the plant. And as it turned out, we found two warheads in the early stage of production, took hammers to them, rendered some of the manufacturing equipment unusable, stopped the manufacturing process and poured our human blood, which we had drawn from ourselves, on the work orders and the blueprints and the office details of this genocidal work.

MIKE BURKE: Could you describe the influence of Father Berrigan on your life and what you feel is most important for people to know about him?

CARRIE SCHUCHARDT: Well, first of all, going back to Vietnam, he had a powerful influence on me. And at the time of Plowshares Eight, I had just taken two Vietnamese boat refugees, and then many, many more, and that led eventually to the founding of the House of Peace for refugees and children of war. Dan was always asking, “How are the children?” And the last visit we made a couple of months, “How are the children?” And the influence of somebody who had such unbreakable, unrelenting moral awareness and direction and courage, and the ability to affirm everybody that was in it with him. And he loved people. He loved the people of this city. He loved—he loved.

AMY GOODMAN: Voices from a procession heading to Father Dan Berrigan’s funeral on Friday. He would have turned 95 years old today.

And that does it for today’s show. I’ll be speaking tonight in Minneapolis at the Parkway Theater and on—tomorrow in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Check our website, democracynow.org.

Media Options