We broadcast from Park City, Utah, home of the Sundance Film Festival, the nation’s largest festival for independent cinema. One of this year’s selections that is creating a lot of buzz is a documentary called The Black Power Mixtape. The film features rare archival footage shot between 1967 and 1975 by two Swedish journalists and was discovered in the basement of Swedish public television 30 years later. We speak with renowned actor and activist Danny Glover, who co-produced The Black Power Mixtape. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: K’naan, singing “Wavin’ Flag.” He was singing in our studios in New York, but he was also singing here this weekend in Park City, Utah, at the Sundance Film Festival. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. And that’s where we’re broadcasting from today — yes, Park City, Utah, home of the Sundance Film Festival, the nation’s largest festival for independent cinema. We’re at Sundance this week to feature independent voices from here in the United States and around the world. More than 200 films and documentaries are being screened and premiered here at Sundance.

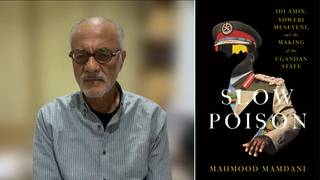

One of this year’s selection that’s creating a lot of buzz is a documentary called The Black Power Mixtape. The film features rare archival footage shot between 1967 and 1975, including some of the leading figures of the Black Power movement in the United States, like Stokely Carmichael, Bobby Seale, Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, Eldridge Cleaver. The footage was shot by two Swedish journalists and was discovered in the basement of Swedish public television 30 years later.

Well, the renowned actor and activist Danny Glover co-produced The Black Power Mixtape. We flew in on Friday night. It was the first film we saw. Yesterday I had a chance to sit down with Danny Glover to talk about the film.

AMY GOODMAN: Welcome to Democracy Now!, Danny Glover.

DANNY GLOVER: Thank you very much, Amy. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Danny, tell us about this film.

DANNY GLOVER: Well, certainly it’s extraordinary. It’s almost, when you think about something like — let’s face it — that we’re dealing with now in terms of WikiLeaks, you know, and how information is uncovered. This film is about information or documentary — documentary filmmakers and interviews with members of — people who were involved in the Black Power movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, this was found in the basement?

DANNY GLOVER: It’s found in the basement — the basement — of Swedish Television. It had been aired only once, as a series. And these incredibly rich interviews — I mean, just from 1967 to 1975.

AMY GOODMAN: Seventy-five.

DANNY GLOVER: Rich interviews of men and women who were involved in the Black Power movement, but also Swedish Television coming to the United States and assessing themselves and interviewing people about the movement. So, you would have an interview, a young sister at the Black Panther Party office in New York who talks about the revolution, you know, or you would have a free breakfast for children program, or you have all this rare footage of Bobby Seale’s in somewhere in Europe. So, this is what this is about. So it’s a compilation of all these interviews, all these documentary films that were done, all this rich archival information about the Black Power movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s play a clip of Stokely Carmichael.

STOKELY CARMICHAEL: Now, let us begin with the modern period of — I guess we could start with 1956. For our generation, this was the beginning of the rise of Dr. Martin Luther King. Dr. King decided that in Montgomery, Alabama, black people had to pay the same prices on the buses as did white people, but we had to sit in the back. And we could only sit in the back if every available seat was taken by a white person. If a white person was standing, a black person could not sit. So Dr. King and his associates got together and said, “This is inhuman. We will boycott your bus system.”

Now, understand what a boycott is. A boycott is a passive act. It is the most passive political act that anyone can commit, a boycott, because what the boycott was doing was simply saying, “We will not ride your buses.” No sort of antagonism. It was not even verbally violent. It was peaceful. Dr. King’s policy was that nonviolence would achieve the gains for black people in the United States. His major assumption was that if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart. That’s very good. He only made one fallacious assumption: in order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none, has none.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Stokely Carmichael —

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —- in this film, The Black Power Mixtape, real rare footage of Stokely Carmichael, who later came to be known as Kwame Ture, going to Sweden -—

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —- and talking about, well, perhaps the differences between him and Dr. King -—

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — talking about the importance of action.

DANNY GLOVER: Yes, yeah. Well, one of the things that, I mean, as you — it’s very interesting. As we’re talking about 1967, so much has happened within the last four years, since the passage of the Voters Rights Act — the riots in Watts, the riots in Detroit, the riots in Newark. And here’s Stokely Carmichael. It so happens that I first met Stokely Carmichael in 1967, when I was a student at San Francisco State. And San Francisco State was very unique in the sense that a number of the members of SNCC, who now decided were going back to school, came to San Francisco and resettled in San Francisco. So Stokely, Ralph Featherston, H. Rap Brown were out at San Francisco State on a regular basis. And so, to hear him talk about, really, what was in 1967 the beginning of his own transition and his own movement from, certainly, the nonviolence — we had had the split in SNCC by that time. There were — we had the removal of white members of SNCC. And all those things were happening at this particular time.

And he began to announce his new path, certainly respectful of King — and I say respectful of King, very respectful of King, as they all were. You know, remember, it was King and Harry Belafonte who initiated the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, put up the resources for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and, not only that, gave it life. So here he is. Here’s the prodigal son breaking away at this particular moment. And certainly, King had been to Sweden. King had traveled to Scandinavian countries to raise money for the movement, which is something that Harry prompted him to do, as well — Harry Belafonte prompted him to do.

AMY GOODMAN: And, you know, of course, Dr. King had won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but the footage in Black Power Mixtape of Dr. King, the king of Sweden raising money for him, and Harry Belafonte in Sweden together.

DANNY GLOVER: Yes, yes. It’s quite remarkable, because it was Harry’s suggestion that they go to Sweden to raise money. Harry, certainly when he first met King in — I believe it was 1956, 1957 — Harry, one of the most popular artists in the world at the particular time, was going to use his influence at the service — in the service of Dr. King, and so — and certainly had very strong connections with Sweden and other Scandinavian countries, as well. So, you hear — this is an incredible moment, you know, and this is something that people don’t know about often, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: And now you, at this time, as you said, San Francisco State — people have heard a lot about Columbia and the student strikes, but the first big shutdown of a university is your own, and you were one of the leaders of it.

DANNY GLOVER: Well, yes, San Francisco State, 1968. And part of this was — we were all moving in some sort of way. The BSU, when I can to San Francisco State in 1966, it was beginning to make its own transition, you know. And why this film was important for me was the fact that it is also my moment, my transition, as well. I had been raised — had been born and raised through the civil rights movement, and now, as the Black Power movement emerged, we begin to assume that —- in fact, we had invited Amiri Baraka out to San Francisco State in the spring of 1967. So, San Francisco State -—

AMY GOODMAN: The poet, activist from New Jersey.

DANNY GLOVER: The poet, activist. And we started becoming the Black Art movement, as well. So here we have the Black Power movement, as we identified by Stokely and the Black Panther Party, etc., and you had students who were involved, as well, myself and others. And the strike came out of that. The strike was an aggressive move by the Black Student Union. And we were fortunate to get allies in terms of the Asian Student Association and the Hispanic Student Association and also progressive white students, that made it successful.

AMY GOODMAN: You were fighting for Black Studies at San Francisco State. Just recently in Tucson, right at the same time of the horrendous shooting, actually, a headline in the paper that day about how they were shutting down ethnic studies.

DANNY GLOVER: They were shutting down the study, yeah. Well —

AMY GOODMAN: But you guys really started the activism for it.

DANNY GLOVER: We’re still — it’s 41 years old, the ethnic studies program. And what was unique, it’s the first ethnic studies program and the only one in any major university in the country. But interesting enough, the first time that I saw Huey P. Newton and had any idea who the Black Panther Party was in 1966, when he came to the Black House and was reading poetry at the Black House. Huey P. Newton — that’s some footage we should have had — reading poetry at the Black House. And at the Black House, Ed Bullins lived. Eldridge Cleaver lived at the Black House. They were two people who lived at the Black House. So, there was — you could see this, and now we’re looking — certainly looking back in retrospect, but you could see this emerging movement happening around, really, what I believe was extraordinary moments of, as I said before, redefining and reimagining democracy, organizing, using those skills. Stokely was an organizer. Those members of SNCC were organizing. So, the Black Power movement was about extending that whole sense of organizing and community organizing.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Danny Glover, is President Obama — or was — a community organizer in the South Side of Chicago. But he’s taken a very different path?

DANNY GLOVER: Well, he made choices, certainly. And certainly, you know, I come out of community service and community development, as well. I worked for the Model Cities Program in the Office of Community Development in San Francisco.

AMY GOODMAN: You were a social worker?

DANNY GLOVER: I was evaluations specialist and program manager in the Model Cities Program from 1972 to 1978, and so — through 1977, rather. And certainly, if you were able to — and this was a very key moment, because this also — as I think about it right now, it also is along the same lines, that parallels what’s happening in the film, that there was an extraordinary level of grassroots democracy happening in communities like the Mission District in San Francisco and the Bayview-Hunters Point district in San Francisco. It is extraordinary. And certainly, it was fueled, of course, by, I think, this sense of organizing that came out of the civil rights movement, and I think also was translated into the Black Power movement, this sense of organizing, this sense of empowerment that people could be the architects for change. And this was happening all over the country.

So, when you look at The Black Power Mixtape, you’re able to kind of reflect on a moment and understand that there are core values at that moment, you know. Yeah, I mean, it was James Brown who, at the same time, came out and said, “I’m black and I’m proud,” at the same time. So, all these particular — this particular energy was happening. And certainly, for them to be able to capture this, be able to — the Swedes be able to capture it, and looking from the outside in, was a critical part of this. They were able to see this from the outside, and asked very — sometimes very innocent questions. That’s certainly that interview — that response by Angela to violence was extraordinary.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to that clip.

SWEDISH TV: Yeah, but the question is, how do you get there? Do you get there by confrontation, violence?

ANGELA DAVIS: Oh, was that the question you were asking?

SWEDISH TV: Yeah.

ANGELA DAVIS: You ask me, you know, whether I approve of violence — I mean, that just doesn’t make any sense at all — whether I approve of guns. I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. Some very, very good friends of mine were killed by bombs, bombs that were planted by racists. I remember — from the time I was very small, I remember the sounds of bombs exploding across the street, our house shaking. I remember my father having to have guns at his disposal at all times because of the fact that, at any moment, someone — we might expect to be attacked. The man who was at that time in complete control of the city government — his name was Bull Connor — would often get on the radio and make statements like “Niggers have moved into a white neighborhood; we better expect some bloodshed tonight.” And sure enough, there would be bloodshed.

After the four young girls who were — who lived very — one of them lived next door to me. I was very good friends with the sister of another one. My sister was very good friends with all three of them. My mother taught one of them in her class. My mother — in fact, when the bombing occurred, one of the mothers of one of the young girls called my mother and said, “Can you take me down to the church to pick up Carole? You know, we heard about the bombing, and I don’t have my car.” And they went down, and what did they find? They found limbs and heads strewn all over the place. And then, after that, in my neighborhood, all the men organized themselves into an armed patrol. They had to take their guns and patrol our community every night, because they did not want that to happen again. I mean, that’s why when someone asks me about violence, I just — I just find it incredible, because what it means is that the person who’s asking that question has absolutely no idea what black people have gone through, what black people have experienced in this country, since the time the first black person was kidnapped from the shores of Africa.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Angela Davis back, oh, 40 years ago in tape that was found in the basement of Swedish public television that has just been made into a remarkable film called Black Power Mixtape. In fact, her face, with her famous afro, is the poster of —

DANNY GLOVER: Poster for the film, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — Black Power Mixtape. Talk about this point that she has raised, about how you raise the issue of violence, Danny Glover.

DANNY GLOVER: Well, it’s very interesting, because — let’s just go back just to step back and think about all these young students — the Bob Moseses, you know, the Fannie Lou Hamers, you know, the Diane Nashes and Stokely Carmichaels and all these. All these people had gone through extreme periods of violence in the South, from the integration of lunch counters to the burning and bombing of buses in the Freedom Rides, and even as they organized, had been beaten, jailed. I mean, it was not — it’s not uncommon — and when we look at the murder of the three civil rights workers, Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney — they’re all not uncommon to face extraordinary, extreme terrorism and violence, and to be able to kind of now, with that, as young people, assume another kind of position and understand violence in a different kind of way and reflect on that violence in a different kind of way.

AMY GOODMAN: It was terrorism.

DANNY GLOVER: It was terrorist. It was terrorism. I went and talked with Bob Moses, and he said, “When you talk about terrorism, I experienced that. About the people that I work with in the South, trying to register them to vote, they experience terrorism on a daily basis, historic terrorism.” So, when we kind of — when we think about that violence, that Angela so brilliantly points it out, you know, that those girls who died in that church were friends of hers, friends of her sisters, lived next door to her. Her mother was a teacher, one of their teachers and everything else.

AMY GOODMAN: It is amazing to think Angela Davis, yes, friends of the little girls in a Birmingham church.

DANNY GLOVER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Condoleezza Rice, Denise McNair, one of the four children, she was friends.

DANNY GLOVER: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: Condoleezza Rice and Angela Davis coming from that same environment.

DANNY GLOVER: Yeah, same environment. Then there’s Connie Rice.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

DANNY GLOVER: Connie Rice in L.A. came from that same environment, one of the great civil rights lawyers in the country, too. You know, so, yeah, it’s — but that moment, though, how she characterizes violence and understanding violence —- and think about that violence now in relationship to what has happened in Tucson. You know, even though we know that this young man is just deranged in some way, there’s the side that drove him to that act, with the kind of vitriol, the kind of nasty, just villainous violence that is happening. The violence that happened even during, you know, town hall meetings in -—

AMY GOODMAN: New Hampshire.

DANNY GLOVER: — during the healthcare crisis, the healthcare debate and everything, all this kind of violence. Then you take, again, that, the war, the wars — King talks about that, how that violence — that violence comes home. That violence comes home to haunt us.

AMY GOODMAN: Actor Danny Glover is the co-producer of the film that has premiered here at the Sundance Film Festival called The Black Power Mixtape. We’ll come back to our conversation with him. We also speak with him about Haiti. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, as we return to my interview with the actor, the activist, co-producer of The Black Power Mixtape, Danny Glover.

AMY GOODMAN: So, here we are at Sundance Film Festival, which is a celebration of independent films.

DANNY GLOVER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the importance of independent films.

DANNY GLOVER: I mean, this is one of the great — for me, after all the blockbusters and everything, this is really — this is one of the great moments, I believe, in my career, to be able to kind of support the independent film, independent thinking. And certainly, if you take the whole genre of independent film — and I use the word “genre,” but if you take independent films, and they invariably have some influence on the industry anyway. Independent film is where the real work that actors get a chance to do, where documentary — and this is why Sundance is so brilliant, about documentary films, you know, and documentaries and everything. It’s so brilliant with this work about that, supporting the idea of documentaries. And when it does that, documentaries are our place and our way of establishing our relationship to what is happening to us. You know, it’s only where — it’s only where there’s some sort of context in which we can look at what is happening to us, have opinions on it, disagree with it, discuss it and have a discourse about it, and perhaps, whether the documentary is about climate, whether the documentary is about healthcare, whatever they are, perhaps have some chance of understanding what the core issues are.

AMY GOODMAN: Certainly, the film that you’ve co-produced, this film Black Power Mixtape, is about movements 40 years ago. And the question is — well, another of the people here, the big films here, is about Harry Belafonte.

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And he is here. And he is raising this question. He said that he feels like he has failed now, as he looks back, whether there will be a new generation of activists following what has been accomplished over the decades, as he walked with King and his activism, aside from his artistry and his music. How do you feel about that?

DANNY GLOVER: I don’t sense that we — of course, we have a 20-year span in our age, and I don’t think — and there’s so much work still that has to be done. But I have no sense of failure. I’m an eternal optimist, as well, you know, and I believe that, as Paul Robeson said, each generation makes its own history. They make their own history. And I think that this generation, that now it’s going to make their history. They’re going to have to respond to the crisis, whether it’s the climate crisis or whether it’s the financial crisis, the crisis of poverty in the world, the crisis of the inequity in the world. They’re going to have to deal with that, you know? And they’re going to have to listen outside of the framework and the constructs that they often have — have really dictated their lives or structured their lives and everything. They’re going to have to do that.

And understand that we can be here forcing that issue, talking about that and talking about — the question is, is that, if we’re going to talk about democracy, what is democracy? And as I said the other night, whose democracy does it belong to? You know? And that’s the fundamental question here. And once we begin to tackle that and struggle against that, we have a chance, you know, because the powers, the powers that be, are going to find every way to undermine it, to subvert it, to stop our voices, to cut off our resources, and find out a way they can do that. But the question is that we have to believe that we can do this and continue to do this.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we end, I want to talk about one of the great crises of today, and it’s Haiti, a country that is very close to your heart. You’ve been making a movie about Haiti for a long time. You visited President Aristide last February in South Africa, who was forced out. We have seen the horrendous earthquake and the effects of that — over 300,000 people killed, a million displaced, now this cholera outbreak.

DANNY GLOVER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And now we see “Baby Doc” Duvalier, a man responsible for the deaths of I don’t know how many thousands of people —

DANNY GLOVER: Of people, yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —- the dictator of Haiti who followed his father, “Papa Doc” Duvalier, the dictator before him, returned -—

DANNY GLOVER: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — when Aristide has not been able to. What are your thoughts?

DANNY GLOVER: It certainly is painful. You know, I, like Frederick Douglass, often refer to myself as a Haitian at heart. And it’s unacceptable that President Aristide is not there with his people. It’s unacceptable that the State Department can say to us that there’s no —- there is no history or there’s no future for President Aristide in -—

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s be clear. P.J. Crowley, the State Department spokesperson —

DANNY GLOVER: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — sends out in a Twitter message — he tweets that Aristide is the past; we have to look to the future in Haiti.

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You were talking about “whose democracy.”

DANNY GLOVER: Whose democracy? Whose democracy?

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe we can extend it to Haiti.

DANNY GLOVER: You know, this country, these people have been under siege for more than 200 years. After the moment after its independence, it’s been under siege. And let’s not lie about it. In every way, in every administration from that time on, from Jefferson to Madison to Clinton to Bush — all of them — every single one of them has done something to undermine Haiti’s ability to stand on its own feet.

Haiti is — these people are so resilient. They are incredible. They’re organizing now. They’re there organizing amidst this chaos. Amidst the cholera, in the midst of — in the midst of the earthquake, in the midst of the lack of functioning government, they are organizing. You know what I’m saying, that every single president, every single administration has been responsible for what’s happening, and every one of them. Yet we don’t know that. We don’t know any of that. We don’t have any of that information right now.

But right now, you’re going to tell me that he is the past, that he has no place and no future in Haiti, is unacceptable. It’s unacceptable that “Baby Doc” has returned to Haiti. That’s unacceptable. And we have to say that’s unacceptable. It’s unacceptable to sanction these flawed elections, as the United States continues to pressure various countries, pressure to OAS and pressure everyone in order to accept these — it’s unacceptable.

And we have to — we’re going to have to, wherever we find — they’re standing up for themselves. When they knocked down the fences and refused to be denied the right to vote during an election of Préval, they made a statement. They want their country back. They want their sovereignty back. They want their independence back. That’s what the Haitian people want. And this is speaking from a Haitian at heart.

AMY GOODMAN: And what is it you think the U.S. finds so — why will the U.S. not allow Aristide to return? Why was the U.S. involved in the coup against him, 1991 to 1994?

DANNY GLOVER: And the other coup in 2004.

AMY GOODMAN: And the coup in 2004, where they sent him off to the Central African Republic into exile with his wife, Mildred Aristide, and then he ends up in exile in South Africa, continually saying he wants to return. What is it the U.S. has against this democratically elected leader of Haiti?

DANNY GLOVER: Well, I don’t know how — what respect the United States has for democracy, anyway, and for people’s right for self-determination, anyway. I don’t know really if they have that. I think it’s part of an ideal, certainly. I mean, but it was part of an ideal — you know, we know our own history. It’s part of ideal. The Bill of Rights came out of — not from the fathers of the republic; it came from people demanding something more than that piece of paper.

So, yeah, what it is is that they must at every point in time undermine the possibilities of democracy in Haiti. And Aristide represents that. And now, you can say whatever you want about Aristide, the fact that he was elected — elected. But in every way, Haiti represents something to the hemisphere. Haiti becoming a true democracy, a functioning democracy, represents something beyond that. Every single country in that hemisphere counts — connects its relationship, its independence, its own sense of sovereignty, its own sense of nationhood, to Haiti.

AMY GOODMAN: I know you have to leave. We just have two minutes. But the power of film is the power of storytelling.

DANNY GLOVER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You have been focused on Haiti, in terms of film, by wanting to tell the story of Toussaint Louverture. And as we wrap up, I was wondering if, in a nutshell, you could tell us that story and why it has grabbed you for so many years as a story you want to pass on to future generations.

DANNY GLOVER: Well, it’s my story. It’s a story — Frederick Douglass said in 1893 at the Chicago Fair that we owe so much to Haiti. José Martí, the great Cuban revolutionary, said we owe so much to Haiti. We owe so much to Haiti, first of all. But it’s an extraordinary story and the only story of its kind ever — ever — in the history of human — that we have written in written human history, that these slaves revolted and challenged the empire. At the outset of the translation, new translation, new construct of capitalism and liberal democracies, here is this country, this smaller country, these people, who at that particular point stand up and say, “It applies to us.” That’s what they said. “It applies to us.” They were defining democracy in a different way than even the fathers of democracy in this country were, even the fathers of the Rights of Man in France were. They were defining democracy. That’s what makes it special. It challenges us. Struggle never concedes upon demand — Frederick Douglass. And that struggle, whatever it was — the demand for independence, demand for sovereignty — is still within the Haitian people’s heart.

AMY GOODMAN: Danny Glover, actor and producer. He co-produced with Joslyn Barnes Black Power Mixtape, directed by Göran Hugo Olsson.

Media Options