Guests

- Scott Shanenational security reporter for The New York Times. Along with Mark Mazzetti and Charlie Savage, he recently co-wrote a front-page article for the Times called “How a U.S. Citizen Came to Be in America’s Cross Hairs.”

As John Brennan is confirmed to head the CIA, we examine one of the most controversial U.S. targeted killings that occurred during his time as Obama’s counterterrorism adviser: the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki. The U.S.-born cleric died in a U.S. drone strike in September 2011, along with American citizen Samir Khan. Al-Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman, was also killed in a separate drone strike just weeks later. On Sunday, The New York Times published a major front-page article on the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki called “How a U.S. Citizen Came to Be in America’s Cross Hairs.” The New York Times’ Scott Shane, one of the reporters on the piece, joins us from Washington, D.C. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As John Brennan is confirmed to head the CIA, we begin today by examining one of the most controversial U.S. targeted killings that occurred during his time as Obama’s counterterrorism adviser: the killing of the American-born Islamic cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. He was killed in Yemen in a drone strike September 2011 along with another American citizen, Samir Khan, the editor of an English-language jihadist magazine called Inspire. Al-Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman, was also killed in a separate drone strike just weeks later. Abdulrahman was born in Denver, Colorado.

On Sunday, The New York Times published a major front-page article on the killing of al-Awlaki called “How a U.S. Citizen Came to Be in America’s Cross Hairs.” The American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights and other groups have condemned the Obama administration’s assassination of al-Awlaki and two other U.S. citizens who were never charged with a crime. But shortly after al-Awlaki was killed, President Obama praised the drone strike.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: The death of Awlaki marks another significant milestone in the broader effort to defeat al-Qaeda and its affiliates. Furthermore, this success is a tribute to our intelligence community and to the efforts of Yemen and its security forces, who have worked closely with the United States over the course of several years.

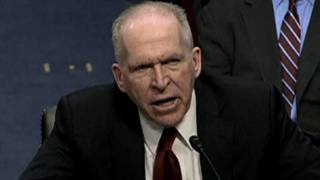

AMY GOODMAN: Eighteen months later, the decision to hunt and kill al-Awlaki resurfaced during John Brennan’s confirmation hearing to head the CIA. During the hearing last month, Senate Intelligence Committee Chair Senator Dianne Feinstein asked Brennan to talk about Anwar al-Awlaki.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Could I ask you some questions about him?

JOHN BRENNAN: You’re the chairman.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: You don’t have to answer. Did he have a connection to Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who would attempt to explode a device on one of our planes over Detroit?

JOHN BRENNAN: Yes, he did.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Can you tell us what that connection was?

JOHN BRENNAN: I would prefer not to at this time, Senator. I’m not prepared to.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: OK. Did he have a connection to the Fort Hood attack?

JOHN BRENNAN: That is a—al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula has a variety of means of communicating and inciting individuals, whether that be websites or emails or other types of things. And so, there are a number of occasions where individuals, including Mr. Awlaki, has been in touch with individuals. And so, Senator, again, I’m not prepared to address the specifics of these, but suffice it to say—

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Well, I’ll just ask you a couple of questions. You don’t—did Faisal Shahzad, who pled guilty to the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, tell interrogators in 2010 that he was inspired by al-Awlaki?

JOHN BRENNAN: I believe that’s correct, yes.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Last October, Awlaki, did he have a direct role in supervising and directing AQAP’s failed attempt, well, to bring down two United States cargo aircraft by detonating explosives concealed inside two packages, as a matter of fact, inside a computer printer cartridge?

JOHN BRENNAN: Mm-hmm. Mr. Awlaki—

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Dubai?

JOHN BRENNAN: —was involved in overseeing a number of these activities, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s John Brennan answering Senator Feinstein’s questions last month about Anwar al-Awlaki, the American citizen who was assassinated in Yemen by a U.S. drone strike in 2011.

For more, we’re joined right now in Washington, D.C., by Scott Shane, national security reporter for The New York Times. Along with Mark Mazzetti and Charlie Savage, he co-wrote Sunday’s front-page article called “How a U.S. Citizen Came to Be in America’s Cross Hairs.”

And here in New York, we’re joined by Jesselyn Radack, former legal ethics adviser to the U.S. Department of Justice under both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, currently the National Security & Human Rights director at the Government Accountability Project.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Scott Shane, could you start off by laying out in detail, as you did in the piece, what you understand were the circumstances leading up to the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki? We’ll begin there.

SCOTT SHANE: Well, Anwar al-Awlaki had been an imam in a number of mosques in the United States. His involvement around the time of the 9/11 attacks remains a little bit of a mystery. He had contact with three of the hijackers. But he certainly presented himself after 9/11 as a fairly moderate guy, a potential bridge builder between the United States and the Muslim world. But after that, in 2002, he moved first to London and then back to Yemen, where his family was. And I think it’s fair to say that he gradually grew more and more radical and more and more open in his calls for attacks on the United States. Eventually, he joined al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the branch of the terrorist network in Yemen. And he—according to Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the 23-year-old Nigerian who—the so-called “underwear bomber” who attempted to blow up an airliner on Christmas Day in 2009, Awlaki had essentially coached him, trained him for that mission.

And so, the Obama administration decided at that point that he was no longer a propagandist for the terrorist network, but it was actually, as they call it, an operator, you know, someone who was actually involved in plotting violence. And they—our understanding is, they put him essentially on a kill list after a legal process. They hunted him for months, and during the months, a much longer legal argument was put together justifying his killing. And finally, on September 30th, 2011, a drone flown by the CIA out of Saudi Arabia found him in Yemen, and his convoy essentially was attacked by missiles, and he was killed.

AMY GOODMAN: And then what happened to his son, Abdulrahman, 16 years old?

SCOTT SHANE: Well, I should say that, along with his death, in the car with him was another man, as you mentioned, Samir Khan, who had spent—had basically grown up in the United States and had also moved to Yemen and was working with al-Awlaki and other members of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and putting out an English-language magazine called Inspire that was aimed to encourage folks to join the jihad against America. And he was with al-Awlaki at the time and was killed in that first strike.

About two weeks later, his son, Abdulrahman, was—had left home in Sana’a, in the capital of Yemen, 16 years old, basically to find his father. And he had learned that his father had been killed, but had not returned home, was sitting at a sort of an outdoor restaurant, a rustic kind of eatery, and a drone strike, an American drone, hit him and the people he was with, killed somewhere around a dozen people, including this 16-year old against whom there was no evidence that he had joined al-Qaeda or plotted violence or had done anything else to—you know, to warrant killing. American officials have portrayed that as a mistake, said they were looking for a or trying to hit an Egyptian terrorist named al-Banna, who apparently was not at that scene. But that—but because the entire episode—the death of the father, Anwar al-Awlaki, and the son, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki—all of that is cloaked in this sort of semi-secrecy that was reflected in Obama’s remarks that you played for us, so it’s very hard to get to the bottom of, you know, exactly what happened in particular with the death of this 16-year-old American.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the white paper, Scott Shane, the legal documents, the rationale on which the targeted killing has been justified, the first and the second, and the people who wrote it?

SCOTT SHANE: Sure. There was—after the underwear bomber was foiled in his attempt to blow up that airliner over Detroit and he began to talk, it became, you know, clear to people that—in Washington, that Anwar al-Awlaki had had this role. And lawyers at the Justice Department in the so-called Office of Legal Counsel, OLC, began working on a legal justification for killing Awlaki. Obviously, it would be a momentous thing—it was a momentous thing—to kill, to target and kill an American citizen based on secret intelligence and with no trial, no court review, basically just on the executive branch’s say-so. They wrote, we were told, a short legal memo. Then, because they—there was a chance, of course, that American intelligence could locate al-Awlaki at any time, but it took months, as it turned out, and so the same lawyers began working on a much longer legal memo covering more possible challenges to the idea that it was legal to kill this guy. And they wrote a 63-page memo, much of which was taken up with legal arguments, but also, probably more than half, on a detailed description of what Anwar al-Awlaki was believed to have done to warrant being killed. And part of their goal, part of the lawyers’ goal, we were told, was to keep from giving sort of sweeping permission to kill Americans in the future on suspicion of terrorism and target this legal opinion very, very tightly to Anwar al-Awlaki and his own actions, his own story.

But the white paper that you mentioned was actually written after Awlaki was killed. And it was when the administration was trying to figure out how much to say about this episode, and particularly the legal reasoning behind it. And they were toying with the idea of speeches, papers. And so, a Justice Department official did a so-called white paper. It was unclassified, but it was kept secret. And it was essentially a sort of quick summary of the much longer legal memorandum used to justify Awlaki’s death, and it wasn’t—it does not specifically talk about Awlaki or give the detailed intelligence on his supposed activities, but it was sort of a sketch of the legal arguments. And, of course, that was leaked prior to John Brennan’s confirmation hearing in February as CIA chief and sort of set off—helped set off this new debate that we’re having, including in Congress for the first time, about targeted killing, and particularly the targeted killing of Americans.

AMY GOODMAN: And interestingly, you point out that these lawyers—David Barron and Martin Lederman—who were in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, had written a book-length, two-part Harvard Law Review essay in 2008, concluding the Bush’s team’s theory of presidential powers that could not be checked by Congress was “an even more radical attempt to remake the constitutional law of war powers than is often recognized.” Then a senator, you point out, Mr. Obama had called the Bush theory that a president could bypass a statute requiring warrants for surveillance “illegal and unconstitutional.” These are the same lawyers that wrote this memo justifying, posthumously, the targeted killings.

SCOTT SHANE: Well, that’s right. Yeah, I mean, when they wrote it, it was not posthumously. The white paper was posthumous, but when they wrote their memo, he still had not been found. I should credit my colleague, Charlie Savage, who did a lot of the reporting on the legal background to this killing. But it was—we were told that those two lawyers were—you know, because of their criticism of the Bush administration and of people like John Yoo and Jay Bybee, lawyers in the Office of Legal Counsel under Bush, they were particularly keen on distinguishing the arguments they were going to make from those that they had criticized under Bush. And I gather that their view was that some of the Bush memos were very sweeping in saying, you know, the president could basically in wartime do just about anything he wanted. And they attempted, successfully or otherwise, in this Awlaki memo, which is still secret, to give enough detail that it was tightly tethered to this guy, Awlaki, and what he had done, what he was alleged to have done, and so that they wouldn’t be accused of, in fact, just sort of justifying willy-nilly anything the president wanted to do against suspected terrorists.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re speaking to Scott Shane, national security reporter for The New York Times. Along with Mark Mazzetti and Charlie Savage, he co-wrote Sunday’s front-page article headlined “How a U.S. Citizen Came to Be in America’s Cross Hairs.” When we come back, we will also be joined, in addition to Scott Shane, by Jesselyn Radack, who is a former legal ethics adviser in the Bush administration’s Justice Department. Stay with us.

Media Options