Guests

- Andy Magerproject coordinator for the Two Row Wampum Renewal Campaign and a member of Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation.

- Oren Lyonsfaithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation, and he sits on the Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs. He also helped establish the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples in 1982.

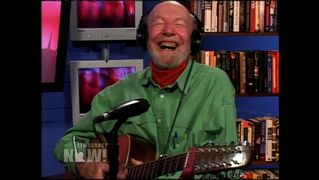

- Pete Seegerlegendary folk singer, banjo player, storyteller and activist.

An extended web-only discussion with two elders, the legendary folk singer Pete Seeger and Onondaga Leader Oren Lyons. They are in New York City today to greet hundreds of Native Americans and their allies who have paddled more than a hundred miles down the Hudson River to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the first treaty between Native Americans and the Europeans who traveled here. The event is part of the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, first proclaimed by the United Nations 20 years ago.

Watch Part 1 & 2 of today’s interviews:

Onondaga Leader Oren Lyons, Pete Seeger on International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples

Pete Seeger Remembers His Late Wife Toshi, Sings Civil Rights Anthem 'We Shall Overcome'

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Pete Seeger, Oren Lyons and Andy Mager. Pete?

PETE SEEGER: And Oren Lyons is one of the wisest men in the world, this Onondaga leader. I have heard him speak on different occasions, and I’ve come away and said, “How I wish this man could be heard by everybody in America, everybody in the world.” He’s a wise man.

AMY GOODMAN: How did the two of you meet, Pete and Oren?

PETE SEEGER: He came to speak for the Clearwater annual meeting, the little—little organization we have trying to clean up the Hudson River. And he came to speak to us. And he—when I heard him, I said, “This man—this man should be heard by everybody.”

AMY GOODMAN: Oren Lyons, on this Indigenous People’s Day, what are your thoughts you’d like to share with our viewers and listeners and readers around the world?

OREN LYONS: Well, as I listened to Pete sing, recognizing the spirit in all of us, the spirit is powerful, and the will, the will to continue and do what has to be done, and responsibility for adults to act like adults, for leaders to act like leaders, and to take away from the corporate powers that are currently in charge of the direction of this Earth and return it back to the people, where it belongs, and also to protect, really be responsible for seven generations of life coming. That’s our mission, and that’s my mission. It’s always been our mission. The mission is peace. The mission is forever. And the mission is friendship, and to understand that the human family is a family—doesn’t matter what color you are. You can change blood. You can’t get any closer than that. And people should understand that.

AMY GOODMAN: What does it mean to be the faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation? And tell us the history of the Onondaga.

OREN LYONS: The Onondaga Nation was the central fire that the peacemaker had to deal with. The Todadaho was the fiercest of all people, and he changed that man. He changed that man. And that is—that proves that no one is above redemption. I don’t care what you do, you can change. And that was a severe lesson to everybody. We remember that. So, today, the Todadaho, Sid Hill, will be up here meeting and greeting with the people and carrying these words of peace. Over a thousand years ago, he was the fiercest, the fiercest enemy of peace. And so, the ideas of democracy, the ideas of leadership by the people and for the people, those are old words. Those belong to our confederation and were taken on by the new government. I think they stalled in several places, but the essence is still there. The essence is still there, but it needs the work of the people. The people have to stand. The people have to move. It’s they who hold the power. They hold the authority, and always did and always will. So, they have to understand that. So, as long as you’re waiting for somebody to tell you to do something, you’re going to wait a long time.

AMY GOODMAN: The significance of the Idle No More movement in Canada?

OREN LYONS: Oh, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain what it is?

OREN LYONS: Well, it’s four women, three Indian women and one white woman, who just said, “This is enough, and we are not going to stand by. We’re not going to be idle no more.” And they challenged the leadership of Canada. And Prime Minister Harper has really challenged the future of people in opening up this huge open-pit mining, you know, that Keystone pipeline, is so intent. All about commerce, nothing about the future. And so, they took a stand, and they said, “We’re not idle anymore.” And, of course, the media never followed it, but it went around the world, and there are people around the world responding to that. It’s a grassroots movement, and it’s a lesson in what you can do if you make your stand. And so, that’s what common people do: lock their arms and stand.

AMY GOODMAN: Andy Mager, Reuters is reporting Chesapeake Energy has abandoned a two-year legal battle to retain leases on thousands of acres of land in New York, where it planned to drill for natural gas using, you know, the controversial technique of fracking, provided the state lift a ban on the practice. Do you know about this and what the significance of this is?

ANDY MAGER: It was announced to our camp that they were abandoning the leases a couple of days ago, not with that last caveat about New York state lifting the moratorium. So, obviously, we would oppose the lifting of the moratorium. We welcome them abandoning the leases and stopping harassing the people of New York state to try to get them to allow this drilling technique.

To get back to what Oren was saying, you know, the purpose of this journey down the Hudson, and the larger campaign of which it’s a part, is to sow seeds to build a social movement, a movement powerful enough to compel New York state and the United States to live up to these treaties and, in doing so, to honor the Earth. And we have been overjoyed by the response we’ve received all the way down the Hudson River from individual citizens, from local government leaders and civic organizations, welcoming what we are doing, providing support, aligning with this broader mission, that we need to honor the treaties that we have signed, to live up to them after 400 years, and to work together for a better future. So we welcome people to join with us today at the pier, in the future through our website, Facebook, etc., because this is not—this landing in New York is in some ways a ending of the paddling journey, but the beginning of a broader movement that we will be looking for support from progressive people, far and wide, to engage in.

AMY GOODMAN: Pete Seeger, I wanted to get your assessment of President Obama. I mean, look at this moment in time. You sang at his inauguration, that remarkable moment, “This Land is Your Land.” We are coming up on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. Actually, President Obama will be standing in the same place as Dr. King did when he delivered his speech, and will give a speech on August 28th in front of the Lincoln Memorial. You were not at the March on Washington, were you?

PETE SEEGER: No, I took my family—my wife and I took our three children out of school, and in 10-and-a-half months we visited 28 countries around the world, small countries. We visited Somoa in the Pacific, and then Australia, Indonesia. And her father joined us. He saw his own family again for the first time in 50 years. He helped the American war effort. He did very dangerous things. He wrote to Washington right after Pearl Harbor, says, “The only hope for Japan is to get rid of the militarists,” because fascists had taken over Japan just like they took over Germany.

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you hear about Dr. King’s speech, “I Have a Dream”? Do you remember?

PETE SEEGER: I read it. I’m a readaholic. And—

AMY GOODMAN: So, somewhere in that journey?

PETE SEEGER: And he was surely one of the most astonishing speakers in the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you ever get to meet him?

PETE SEEGER: I met him only twice—once very briefly when he—just a year after the bus boycott, where he first became well known—

AMY GOODMAN: In Montgomery?

PETE SEEGER: No, he came to the little school in the Highlands of Tennessee, called the Highlander Folk School. And that’s where he heard me sing “We Shall Overcome.” And then, I was singing a few songs in the street outside the United Nations when he made perhaps the most—one of the two most important speeches. He said, “I have to face the fact that my own country is the greatest purveyor of violence. We must get out of Vietnam.” I’m sure—

AMY GOODMAN: You were at Riverside Church, April 4th, 1967?

PETE SEEGER: No, I was in the streets, where he gave the same speech a day later outside the United Nations. And I was up on the speakers’ stand when I saw a black car inching its way through the crowd. And I heard people: “He’s here! He’s here!” He got 20 feet away from the speakers’ stand, and the door opened, and Dr. King got out. It took six strong men to help him—to make it possible for him to make 20 feet from the car to the speakers’ stand. I said, “How can anybody live with this kind of adulation?” Well, I’m sure—I have absolutely no proof, but I think that’s when LBJ lost his temper. He said, “After all I did for that guy, look what he does to me!” He probably picked up the phone to J. Edgar Hoover, said, “Do what you want!” Slam!

AMY GOODMAN: What was Dr. King’s reaction to hearing you sing “We Shall Overcome” at the Highlander Center?

PETE SEEGER: Oh, he was sitting in the backseat of a car, while a woman I know, wonderful woman, was driving him to some speaking engagement up in Kentucky. He said, “'We Shall Overcome,' that really—song really sticks with you, doesn’t it?”

He—at only age 14, some man wrote a letter to the big newspaper in Atlanta: “Why do Negroes want to marry white? Don’t they know that we’re supposed to be separate people?” And this 14-year-old writes a letter to the editor of the newspaper: “Surely, Mr. So-and-So, whoever wrote this letter, must know that if there are people in America of mixed ancestry, it’s not because Negroes want to marry whites, but because of aggressive white males taking advantage of defenseless black females.” In one sentence, he said what most people would have taken paragraphs to say.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Martin Luther King when he was 14 years old?

PETE SEEGER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: What is your assessment of President Obama?

PETE SEEGER: I wish that he had made so few compromises that he would not have gotten re-elected. And then, four years later, he would have gotten re-elected, because the contrast between what he did and the people who took over for the four years in between would have been obvious to the whole world.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I know that you all have to go to the pier to meet the rowers who are coming up the Hudson.

PETE SEEGER: We do.

AMY GOODMAN: But I was wondering if you could take us out on a song, maybe the hammer song, “If I Had a Hammer,” which was sung by Peter, Paul and Mary at the March on Washington, your song, 50 years ago, August 28th.

PETE SEEGER: Well, Woody Guthrie was one of the greatest songwriters I knew, but the bass in The Weavers, a man named Lee Hays from Arkansas, was another one of the geniuses. And he knew that a lot of old gospel songs, just change one word, and you’ve got a new verse. So he sent me four verses, says, “Pete, can you make up a tune?” I tried to, but it wasn’t as good a tune as it should have been. And Peter, Paul and Mary improved my tune. And then the song went around the world. Marlene Dietrich toured the world, and—no, she sang “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” But the song, “If I Had a Hammer,” went all sorts of places that I could never go, and I’m very glad.

[singing] If I had a hammer,

I’d hammer in the morning,

I’d hammer in the evening,

All over this land,

I’d hammer out danger,

Hammer out a warning,

Hammer out love between,

All of my brothers,

Oh, a woman said, “Make that 'My brothers and my sisters.'” Lee says, “It doesn’t roll off the tongue so well. But she insisted. He said, “How about 'All of my siblings'?” She didn’t think that was funny.

[singing] All over this land.

If I had a song,

Don’t need to sing the whole song. You can sing it to yourself, whether you’re driving a car or washing the dishes or just singing to your kids. We haven’t mentioned children much on this program, but it may be children realizing that you can’t live without love, you can’t live without fun and laughter, you can’t live without friends—and I say, “Long live teachers of children,” because they can show children how they can save the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Can we end with “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” for the children?

PETE SEEGER: No. You sing it.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to end on a lovely note.

PETE SEEGER: No. I’ve sung lots of songs. And the other day, a group of Japanese Americans remembered Hiroshima, and I sang four short verses.

[singing] We come and stand at every door

But none can hear my silent tread

I knock and yet remain unseen

For I am dead, for I am dead.

I’m only seven, although I died

In Hiroshima long ago.

I’m seven now, as I was then.

When children die, they do not grow.

My hair was scorched by swirling flame;

My eyes grew dim, my eyes grew blind.

Death came and turned my bones to dust,

And that was scattered by the wind.

I need no fruit, I need no rice.

I need no sweets, not even bread;

I ask for nothing for myself,

For I am dead, for I am dead.

All that I ask is that for peace

You fight today, you fight today.

So that the children of this world

May live and grow and laugh and play!

AMY GOODMAN: Pete, thank you so much, and especially on this day, August 9th, the anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki 68 years ago, three days after the bombing of Hiroshima 68 years ago.

PETE SEEGER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And now you head to greet the rowers coming down the Hudson.

PETE SEEGER: Mm-hmm, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And I thank you so much for being with us. Peter Seeger, Oren Lyons, Andy Mager, thanks for giving us a gift today.

ANDY MAGER: Thank you, Amy.

OREN LYONS: Thank you, Amy.

Media Options