Guests

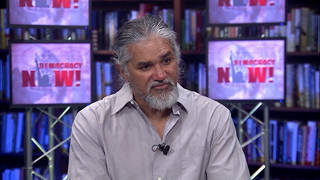

- Ravi Ragbirwell-known immigrant rights advocate and executive director of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City.

- Amy GottliebRavi Ragbir’s wife and a longtime immigrant rights advocate with the American Friends Service Committee.

UPDATE: Ravi Ragbir was released after his ICE check-in after arriving at the meeting surrounded by hundreds of supporters. Watch live coverage on our Facebook page.

One of New York’s best-known immigrant rights advocates joins us on what might be his last day as a free man in the United States. Ravi Ragbir is executive director of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City. This morning, right after our broadcast, Ravi heads for a check-in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He plans to go to the meeting, even though he may not be released. Ravi legally immigrated to the United States from Trinidad and Tobago more than 25 years ago, but a 2001 wire fraud conviction made his green card subject to review. Even though he is married to a U.S. citizen and has a U.S-born daughter, the government refuses to normalize his status. Just last month, Ravi was recognized with the Immigrant Excellence Award by the New York State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators, given to those who show “deep commitment to the enhancement of their community.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show with a Democracy Now! exclusive. One of the New York’s best-known immigrants’ rights advocates joins us on what might be his last day as a free man in the United States. Ravi Ragbir is executive director of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City. This morning, right after our broadcast, Ravi heads for a check-in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement here in New York City. He plans to go to the meeting, even though he may not be released.

The usually predictable process of checking in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement as part of a regular supervision process has become a source of anxiety for many immigrants since President Trump ordered changes to enforcement in January. In just one example, last week in Phoenix, Arizona, a single father of three U.S.-born children had plans to celebrate his son’s 17th birthday after a check-in meeting that he thought was to discuss his request for asylum. An hour later, Juan Carlos Fomperosa García’s daughter says officials, quote, “brought me a bag with his stuff and that was it.” Her father was deported the next day. Meanwhile, other immigrants have gone to their check-ins and were released as expected.

No matter what happens this morning at Ravi Ragbir’s check-in, he will not go alone. As part of his work, he has conducted trainings on how to accompany people to their check-ins in order to show support and document what unfolds. He, himself, will be joined by faith leaders and elected officials, including several city councilmembers and New York state Senator Gustavo Rivera. Just last month, Ravi was recognized in Albany, the New York state capital, with the Immigrant Excellence Award by the New York State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators, given to those who show, quote, “deep commitment to the enhancement of their community,” unquote. The Indypendent newspaper recently featured him in a cover story called “Walk With Me,” by Democracy Now!’s Renée Feltz. And a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation film crew is following him today.

Ravi legally immigrated to the United States from Trinidad and Tobago more than 25 years ago, but a 2001 wire fraud conviction made his green card subject to review. Even though he’s married to a U.S. citizen and has a U.S.-born daughter, the government refuses to normalize his status. Instead, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has exercised prosecutorial discretion to grant him a stay of deportation. His current stay lasts until 2018. But his 15-year-old criminal record makes him an easy target for removal.

Last night, his supporters and legal team met for one last time before this morning’s check-in. This is Rhiya Trivedi, a third-year law student at NYU School of Law, who’s helping represent Ravi through the school’s Immigrant Rights Clinic.

RHIYA TRIVEDI: You can see that, for many, many years, the ICE office has recognized the outstanding contribution that he has made to the community as a leader, as someone in the faith community and the immigrant rights community. He’s a very important person to a lot of people. And they have recognized that, and we expect that they will continue to do that. So, we prepare for the worst; we expect the best.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Rhiya Trivedi. Well, this morning, Ravi Ragbir joins us in our studio before he heads to check-in. Also joining us, his wife, Amy Gottlieb, a longtime immigrant rights lawyer with the American Friends Service Committee.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now!

RAVI RAGBIR: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: I know this is a really tough time for you right now. Ravi, talk about what you will do after you leave Democracy Now!

RAVI RAGBIR: Well, I will just head to the subways. You know, basically, I’m going—

AMY GOODMAN: You’ll head to the subway.

RAVI RAGBIR: I’m going to the subway.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re going underground.

RAVI RAGBIR: I am going underground. That’s absolutely true. But we—you know, normally, some people will say, why don’t I go underground? But that’s not an option here. And that’s—I am not going to do that. I am going to Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices at 26 Federal Plaza. And I’m going to basically turn myself in and hope and expect that they will allow me to come back out. And there’s a stay. You mentioned the stay of removal that expires in 2018. That will be a normal expectation, that they will release me, because they gave me this stay. But as you said, there are many instances that people have not been—have been taken away and end up deported.

AMY GOODMAN: When you say you’re going to turn yourself in, what you’re doing is you’re going for a check-in, which can be very routine in the United States for immigrants.

RAVI RAGBIR: Absolutely. So, it is a routine check-in. It’s like a parole—right?—for analogy. And you just go in to meet your deportation officer, and he would make sure all information is correct, and normally we would walk out. But not in this instance. And that’s what is going to happen. And that’s why—you know, you mentioned the accompaniment. When we partner U.S. citizens with immigrants who are in this crisis—not only for myself, for many others—they are able to get the support from the community, and so they are not in this fearful space, but also getting the officers to treat that person with respect.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, this is actually amazing, because you really pioneered this accompaniment program for check-ins, which most people don’t really think about, where people accompany an immigrant to check-in.

RAVI RAGBIR: So, people have been accompanied before, but we have had a training to have them understand what they need to do, their response in different scenarios, and not only to the check-ins, but to the court. So, a lot of times the lawyers will say they don’t need any family or friends: “I’m the lawyer. I will get you out.” But, in actual fact, when the community is there, the minister—especially the minister—and the congregation, it makes a difference when, in that judge’s eyes, there is such a large support and such a large community here, that they make—it makes a difference. And we have gotten people freed. We have gotten people—the judge has said, “OK, you have won your case because of the large community support.” So, yes, it is something that is unique to the New Sanctuary, where the training is very, very important for the immigrant as much as the volunteers.

AMY GOODMAN: But here, there is no judge. You will meet with an ICE officer.

RAVI RAGBIR: I will meet with a deportation officer.

AMY GOODMAN: A deportation—and do know that person? You’ve been doing this for years.

RAVI RAGBIR: I’ve been doing this for years, and it changes every time. Maybe one time we have had the same deportation officer. But we never know who is going to be the officer on file, and I never know who I’m going to be meeting today. So, sometimes the officers are friendly. Sometimes they’re not. And that uncertainty of who we’re going to meet—you know, before, when I had—I had a two-year stay in 2014. The officer said, “OK, we’ll see you in two years.” In 2016, when I went back to renew it, the—and we got it—the officer said, “I’ll see you in one year.” There’s no—there was no rhyme and reason why I had to go back in today. But, you know, as my wife will say, it’s probably the best thing, that we had to come in, so I will not be looking over my shoulder every day.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Amy, you’re Ravi’s wife. You also happen to be an immigrants’ rights attorney. How long have the two of you been married?

AMY GOTTLIEB: We’ve been married about six-and-a-half years. We got married in September of 2010.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Ravi, how long have you been in the United States?

RAVI RAGBIR: I’ve been in the United States since 1990, just over 25 years.

AMY GOODMAN: For a quarter of a century. So, Amy, how are you doing today?

AMY GOTTLIEB: Ooh, I’m OK. You know, we have been through this before. It does feel different. What feels good is the outpouring of community support that we have right now, knowing that we, honestly, have the best legal team on Earth, the best organizing team on Earth. We have a committee, a defense committee, that is helping us kind of strategize about what to do if he gets taken in, how to celebrate if he doesn’t get taken in. So, we’ve been taking it one day at a time, feeling, of course, anxious, not sleeping so well, but at the same time holding out hope that ICE will, you know, continue the existing stay and that we have more time to continue real legal options to help Ravi get full legal status here.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you go in together to—it’s almost like a DMV-like room, right? Department of Motor Vehicles. You’ve got Fox News on the television. And then your number is called?

RAVI RAGBIR: Well, not a number, but we will turn in the paperwork, the supervision paperwork, to the window, like a DMV window. And they will put it—they will leave it for the deportation officer to pick up. And then the officer will come out and either call me to the door and say, “OK, come back in six months or a year,” but in another scenario, he will call me in to say, “I need to talk to you.” And you will not see me again.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Amy, can you be with him through this time?

AMY GOTTLIEB: It depends—I mean, I can be with him, waiting. And it depends if they bring him back or not. In previous years, they have allowed me back, if they call him in to like have a quick conversation. But you just can’t predict, right? You just don’t know how they’re going to act.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you could be taken, and you just never see Ravi here in this country again.

AMY GOTTLIEB: It’s possible. We have heard of times where a person we knew a couple years ago got taken in, and he was accompanied by people we knew, and they allowed them back there to say goodbye. So it’s possible that they would do something like that. But as I said, you know, it depends on the officer. It depends on a lot of different scenarios.

RAVI RAGBIR: And that was the accompaniment program, right? The volunteers from the accompaniment was allowed to speak, to be there. But it’s a different era now and different atmosphere. So, what we would have expected, we cannot expect anymore. So, it’s totally unknown.

AMY GOODMAN: So, if President Obama were still in office, they—under him, they had granted you a two-year stay. So, although they said you had to come back this year, you would have another year until hoping to get another stay, as you work out your green card and your residency status.

RAVI RAGBIR: That’s right. We would have expected to go in, it would the routine check-in, and they’ll say, “Well, you have the stay. We will see you back in another—in another year.” But even if there was another administration, we would have expected something similar.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let me turn to President Trump speaking just last month.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I said we will get the criminals out, the drug lords, the gang members. We’re getting them out. General Kelly, who’s sitting right here, is doing a fantastic job. And I said, at the beginning, we are going to get the bad ones, the really bad ones. We’re getting them out. And that’s exactly what we’re doing. I think that in the end, everyone is going to be extremely happy.

AMY GOODMAN: “We’re going to get the really bad ones out.” Amy?

AMY GOTTLIEB: Yeah. You know, for so many years working on these issues, we have been really struggling to eliminate this idea that there’s a good immigrant and a bad immigrant—right?—that we have people who come to our country who are people who have lives that—you know, sometimes there’s a criminal conviction, there’s a bad act, but we want folks to be able to look at the whole person. And when you hear that kind of language about, you know, getting the bad people out, it stirs up something inside of me that—you know, that’s not Ravi, right? Like, we’re not talking about bad people here. We’re talking about the people who are part of our communities. That’s just rhetoric that, you know, kind of pits people against each other.

AMY GOODMAN: Ravi, you had a criminal conviction how many years ago?

RAVI RAGBIR: I was convicted in 2000.

AMY GOODMAN: For a wire fraud conviction.

RAVI RAGBIR: For wire fraud, working as a salesman for a mortgage lender.

AMY GOODMAN: And how long did you serve in jail?

RAVI RAGBIR: I was sentenced for two-and-a-half years. I was under house arrest, before I was sent and before I served the two-and-a-half years, for three years before that. So, three years I was under house arrest, and then I went into jail, prison, for two-and-a-half years, and then I ended up in detention for two years.

AMY GOODMAN: So then they wanted to deport you right after that.

RAVI RAGBIR: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: But you fought that and won.

RAVI RAGBIR: I fought that, and we have been fighting that since then. So it has been—this is where the legal team, Rhiya and my legal team, my attorney, Alina Das, have been saying that this process—that “this process”—and I use air quotes, right? Because the process itself was completely wrong. And they can point to many errors in the process itself.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to a different case, to Rose Escobar, speaking last month in Houston, Texas, after her husband, Jose, the father of their two children, was detained when he showed up for his annual check-in, and almost immediately deported.

ROSE ESCOBAR: My husband is not a criminal. My husband is a good man who works hard and provides for me and my children. My husband already makes America great. You take him away from me, you have me going to welfare, food stamps. That’s not the life that I want. I’m not saying it’s a bad life, but that’s not the life I had, and it’s not the life that I want.

AMY GOODMAN: Amy, that’s the wife of Jose. You’re the wife of Ravi. Your feelings right now as you head down to Federal Plaza? The two of you, as soon as you arrive, will be holding a news conference. Is that right? Hundreds of people are expected. I went down to the offices at the Judson church last night. There were scores of people there saying goodbye to you, Ravi, being there to support you, making a whole big dinner, making signs. And in these last weeks, you haven’t stopped talking to people, advising them about what to do in their cases, taking phone calls, learning about ICE raids throughout New York.

RAVI RAGBIR: In actual fact, last week I went to Union City. The mayor of Union City had worked with us—

AMY GOODMAN: In New Jersey, Union City.

RAVI RAGBIR: In New Jersey. And he issued a municipal ID six weeks after we talked to him, and he called for a town hall. And he expected 50 people. Sixteen hundred people showed up in a church that was only supposed to hold 500. And those were the people who were allowed inside. There were hundreds outside. People are afraid. They need to have this information. And, yes, you’re right: I have not stopped speaking, I have not stopped doing presentations, because it is—it’s a number—the immigrants themselves, the people who want to support them, the churches who need to be ready to have—to create a safe space, we—everyone is—we need to coordinate that.

Now, what you saw yesterday wasn’t—last night wasn’t a goodbye, but an empowerment dinner, because that’s what we do. We empower people through this process. They’re afraid. Most of them who you met there, the parents are undocumented themselves. But because we have been able to teach them how to deal with this process, they are strong, and they’re energized, and they’re motivated to speak up and also to move forward. So they will be down there today.

AMY GOODMAN: What is a Jericho walk?

RAVI RAGBIR: Jericho walk, it is biblical. It’s in a story in the Bible, where they couldn’t defeat the city. And God told them, “Well, you cannot defeat the city by army, but you follow my instructions, and you will win.” So they were told to walk around seven times around the city. And after seven times, the walls came tumbling down. There’s a song about that.

But, similarly, we have been doing a Jericho walk since 2011, which started as a result of—in response to SB 1070, the Arizona law. We walk around Federal Plaza seven times in silence. We—

AMY GOODMAN: This is around Federal Plaza, 26 Federal Plaza, area?

RAVI RAGBIR: It is around 26 Federal Plaza. And we have done it around 26 Federal Plaza. We’ve also done it around the Supreme Court. Five hundred people have walked around the Supreme Court. We have walked around Congress. We have walked around the Senate building. In silence. And, you know, when the guards or the officers see us, they don’t know what to take of—what to think about us, because we’re not saying a word, but you know we’re there for a purpose. Similarly, the Jericho walk today is going to be doing that.

AMY GOODMAN: If you are taken, where would you be taken to? Where are immigrants taken in New York City when they are detained?

RAVI RAGBIR: It could be a number of places. They could be taken to New Jersey, Hudson County Correctional Center, the Bergen County Jail, or I could be taken to Orange County up in [Goshen], right? Upstate New York. So, any one of them, I will be held and detained until they find—they can put me on a plane and take me to Trinidad.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Amy, you are an immigrants’ rights lawyer. For a long time you ran the Newark office of AFSC. That’s in New Jersey.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Yeah, that’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: These detention centers mainly are for-profit detention centers. The Elizabeth Detention Center, I think, is run by CCA.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: The Corrections Corporation of America. These for-profit jails are enjoying massive profits since President Trump was elected.

AMY GOTTLIEB: That’s right. In New Jersey, there’s actually only one that’s private. That’s the Elizabeth Detention Center, as you say. There’s also these county jails that contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and make tons and tons and tons of money for the counties themselves. So they celebrate when they get these contracts, because they’re paid approximately, you know, $120, $130 per day per detainee. So, they—Hudson County, for example, has over, I think, 900 beds. Essex County Jail has over 800 beds. So we’ve got people detained everywhere. Profits are soaring. Prior to President Trump, President Obama’s administration had actually said they were going to stop using private prisons in the federal prison system. We were pushing to have that happen in immigration detention system. We got close to that. And then Attorney General Sessions came in and completely retracted that. So we’re back into private prisons and all the private companies that contract with public prisons that are making money on this.

RAVI RAGBIR: So, you know how much it costs to feed—when I was locked in detention, do you know how much it cost to feed me for one day? Seventy-five cents. They were spending to feed one immigrant 75 cents. And you know how we knew that? Because they felt they were spending too much, and they wanted to bring that cost under 45 cents, so the numbers were thrown out, and we were hearing and seeing this happen. So, the profits—the cost is low, but the profits are high, because they’re being paid $120, right?

AMY GOODMAN: So, have you packed? People often don’t know that they’re going to be taken. But you confront this epic moment right now, after being in this country for 27 years. How did you prepare for this morning?

RAVI RAGBIR: I did not pack. My wife has been telling me to clean up, but I haven’t done that. I’ve ignored that. Basically, how I prepared is throwing myself in my work. I’ve been doing presentations two and three times a day, sometimes speaking for four hours straight to congregations or churches. So, that’s how I’ve dealt with this. Last night you asked me how I felt. Well, I told you I had no feelings, because if I was going to feel something, I was going to feel terror, I was going to feel anxiety. And to feel that and be able to work, be able to function, was impossible. And I couldn’t allow myself to curl up in a corner and die, which is where they want us to be. I had to continue doing the work and continue to share the experience, so that as the privileged person that I am, meaning that I can go back to Trinidad without feeling that fear that I could be targeted, as other countries and other immigrants face, also I’m able to speak, and I also have community support. So I’m privileged, and I use this opportunity to highlight that situation.

AMY GOODMAN: Who will be speaking today at the news conference, just as this show ends, that you’ll be holding at right outside 26 Federal Plaza?

RAVI RAGBIR: We have been told that apart from the faith communities, that, you know, Reverend Donna Schaper will be speaking. But, we have heard, the elected—

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend Donna Schaper is the reverend of the Judson church, where the New Sanctuary Coalition has its offices?

RAVI RAGBIR: That’s right. And she’s the one who—she was one of the co-founders of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York, but also of the National Sanctuary in 2007. But apart from that, they have a lot of elected officials who are coming to support me, to walk in with me. So, Senator Gustavo Rivera will be there. You have Councilman Dromm, Councilman Williams, Jumaane Williams, Councilman Rodríguez. The speaker just confirmed—Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito just confirmed she will be there.

AMY GOODMAN: The speaker of the New York City Council.

RAVI RAGBIR: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Melissa Mark-Viverito will be also speaking and accompanying you?

RAVI RAGBIR: Yes. We don’t know if she’s accompanying us, but she’s speaking at the press conference. The controller is planning to be there. We have had two state Assembly people who also want to speak, [inaudible] and—

AMY GOTTLIEB: Jo Anne Simon.

RAVI RAGBIR: Jo Anne Simon.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Is our assemblywoman.

AMY GOODMAN: The assemblywoman in the state Legislature.

AMY GOTTLIEB: In our district, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And then you will, together, walk into the ICE office.

RAVI RAGBIR: Together, we will go through security. You know, they make you take your shoes off—right?—to get into that building, take your belts off and ask you for ID. And a lot of people who are going into that space don’t have ID, so they intimidate you from the beginning. And when you go upstairs, you are having to turn in—to hand in this paperwork and sit down there in complete terror, because every minute that goes past, you are thinking that this is the day. And you’re sitting next to people who are facing that same trauma. And they, themselves, are—we feel that fear. And you sit down, and you see the child and the wife, who may have accompanied them, and the tears and the heartbreak that is happening because they are being ripped apart. So, it is—it is hard for me, as a person, to see that, all while I’m going through it myself, but this is why we have had the accompaniment training. So we want people to see that, so they can take it back out and force and push for true reform, where people can live in dignity without that fear.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see yourself as a role model?

RAVI RAGBIR: I do not want to think of myself as a role model, because then it clouds where I need to be. You know, I need to be always aware that even though I may—that even though I may have support, I have to think about those who do not have support. So I always have to be ready to think about the consequences of a policy change on someone who do not have—who do not have that support. But, you know, what you saw yesterday is those immigrants who says I’ve been a role model for them, so that they are now speaking up, and they are now empowered to go out and speak to the elected officials and go out and advocate for themselves and go out even though something may go wrong. They know that, as they go through this process, it will be good for them, because they’re ready for every step of the way. So, I do not want to be a role model, but I have been told I am.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you have a message for President Trump?

RAVI RAGBIR: I will let my wife answer that.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Ooh, if only. God, I would desperately love for us to have a president who saw the humanity in every single individual and understood that every person should be treated with dignity and respect. That’s my message. And that all of our policies should reflect that.

RAVI RAGBIR: Not only for immigrants. We’re talking about he has been, you know, using other rhetorics that has—is targeting and causing—as a result, there’s a lot of hate that is on the streets. We need to look at everyone as being part of a society that wants to grow together and walk together. So, we need to—everyone needs to be able to build that relationship together.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to end back in your basement, where you were last night, the basement of the Judson church in New York City, to go to Judith Paez, who was speaking during what could be your last meeting at the New Sanctuary Coalition. People were making banners for today’s Jericho walk outside 26 Federal Plaza. This is Judith.

JUDITH PAEZ: We started making these banners yesterday. And we had the idea a few weeks ago about doing all this kind of art to represent what we are here in the sanctuary. We are fighting for our rights, but not just a fight. It’s not just a fight. It’s something to show support, to show unity, to show strength in our communities, that have been suffering for all these new government—you know, the policies that are separating families, are breaking apart many, many families in this city and many other places around the U.S.A.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Judy Paez in the basement of the Judson church. As we wrap up, this is right when kids are going to school, but a lot of kids are afraid. Their parents don’t want to send them to school, afraid, like we just played the video that has gone viral of the dad taking his 13-year-old to school, and he is arrested, and she’s weeping as she’s filming this on her phone. What do you say to these families? Are you finding that families are taking their kids out of school?

RAVI RAGBIR: We are finding that they are taking their kids out of school. The kids that are going to school, they have had many teachers and principals call and say, “Can you come and do a Beyond the Rights training?” So, you know, we do—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean by “beyond your rights”?

RAVI RAGBIR: Well, the rights, the Know Your Rights, that is—that we used to say before, basically stops at: If they knock on the door, don’t open the door. But if they—if we expect this administration—we don’t know what rights could be violated, and we have to have everyone prepare for that. So, during this process, if they get captured, what do they need to do? They don’t have to sign any stipulated waivers, so that they have to go through the court system. It’s sharing with people that they will not get deported immediately. There is a process. And that process could take months and even years. When I was in detention, I met someone who was there for seven years in detention. He still got deported, but he was fighting throughout that seven years, hoping that he could stay here. And we will speak to the parents about this process, so they are not afraid. As I was saying, the principals will call because those children are crying. They don’t stop crying, because they don’t have their parents to be home when they leave school. And how does that environment facilitate learning? You know, you would think that only applies to the young children, you know, the 10 and under, but the elderly—the older children are feeling this also. And everyone wants to—needs this help and needs to know the Beyond the Rights, so that they know how not to get caught and how not to—how to navigate the process every step of the way.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, all the best to you both. We will continue to follow what happens to you, and people can go to democracynow.org, as we go down to 26 Federal Plaza, where you’ll hold your news conference, and then you’ll make your way up into the ICE facility. And we’ll see what happens next.

RAVI RAGBIR: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: We hope to see you again, interviewing you as you come out and say how you felt coming out again as a free man.

RAVI RAGBIR: I hope so. I hope to be back here talking to you.

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you so much, Ravi Ragbir and Amy Gottlieb.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Ravi, well-known immigrants’ rights advocate, executive director and founder of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City, he faces deportation when he goes to his ICE check-in this morning after our broadcast. But first there will be a news conference, and we will be covering that at 9:00 at Federal Plaza, right outside 26 Federal Plaza.

AMY GOTTLIEB: At Foley Square, right.

AMY GOODMAN: At Foley—

AMY GOTTLIEB: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Right at Foley Square.

AMY GOTTLIEB: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: I know hundreds of people are planning to go. This is Democracy Now! When we come back, immigrants’ rights, the Muslim ban, reproductive rights—all of these issues were raised yesterday, not only in the United States, but around the world. In the United States, it was called A Day Without a Woman. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: That was music recorded last night at Judson Memorial Church in New York City at a gathering for Ravi Ragbir ahead of his check-in with ICE today. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options