We begin our coverage of what some are calling “Striketober” with a look at how the union of 60,000 television and film production workers averted a strike just hours before a midnight deadline on Saturday, when it reached a tentative agreement with an association of Hollywood producers representing companies like Walt Disney, Netflix and Amazon. The tentative deal brings members of IATSE, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, higher pay, longer breaks, better healthcare and pension benefits. Some members say the deal doesn’t go far enough, and about 40,000 members from 13 Hollywood locals must still approve the pact. Jacobin writer Alex Press says the averted strike is part of a “broader moment” of labor militancy across the United States, including workers at Amazon, Kellogg’s and elsewhere. “Workers are willing to fight back,” she says. “They understand they have more leverage right now.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show with what a number of people are calling “Striketober,” as workers across the United States in a wide variety of industries are walking off the job. Thousands have gone on strike at food plants operated by Kellogg’s, Nabisco and Frito-Lay over work hours, pay and benefits. Last week, more than 24,000 Kaiser Permanente healthcare workers in California authorized a strike. Now 10,000 United Automobile Workers members at John Deere are also on strike, saying they were forced to work overtime while the company made record profits. The list goes on and includes more than 1,000 coal miners on strike at Warrior Met in Alabama, as we’ve covered here at Democracy Now!

This comes as the union representing television and film production crews averted a strike of some 60,000 workers just hours before a midnight deadline Saturday, when it reached a tentative agreement with an association of Hollywood producers representing companies like Walt Disney, Netflix and Amazon. The tentative deal brings members of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees higher pay, longer breaks and better healthcare and pension benefits. Some members say the deal doesn’t go far enough, and about 40,000 members from 13 Hollywood locals must still approve the pact.

These are two IATSE members in Los Angeles — costume maker Yuan Thueson and Thomas Pieczkolon, who works in sound production — in a video by More Perfect Union.

THOMAS PIECZKOLON: We take one break at six hours on the contracts that our unions negotiated long ago. They’re trying not to actually have us break, because, for them, if they don’t break us for lunch, they pay a meal penalty. Those meal penalties haven’t been updates since the mid-'80s. So, for them, it's pennies. They can make us work 10 hours, 11 hours straight and pay four to five meal penalties, but it doesn’t affect them at the end of the day when it’s Amazon and the show has a $300 million budget.

YUAN THUESON: We see the big companies producing big budget projects, and we know that they’re popular, they’re selling, and people are watching it. But our crew who’s working on those projects are getting paid like $5 to nearly $10 less an hour, just because it’s new media.

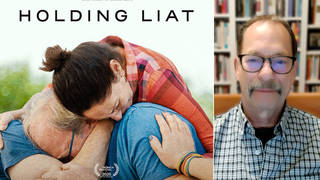

AMY GOODMAN: For more on this U.S. strike wave, we’re joined in Pittsburgh by Alex Press, staff writer at Jacobin, where one of her recent pieces is headlined “US Workers Are in a Militant Mood.” She’s also host of a podcast about Amazon workers called Primer. In a few minutes, we’ll also speak with a John Deere worker on strike in Iowa, and we’ll talk with a representative of the taxi workers who are going on hunger strike in New York. But first let’s look at this strike that was averted, the IATSE workers, 60,000 of them.

Alex Press, can you talk about IATSE and then go broader to Striketober?

ALEX PRESS: Sure, yeah. Thanks so much for having me, Amy.

So, this is a big story, as you said, based on sheer numbers, right? Sixty thousand IATSE members voted nearly 99% in favor of authorizing a strike, and 90% of eligible members cast ballots in that vote. That would have begun a strike on Monday that — had they not reached that deal late on Saturday night, that strike would have been the largest one in the private sector in the United States since one by 74,000 workers at GM into 2007. So, the numbers on that strike authorization vote reflect a charged-up, mobilized membership.

The reason for their sense of urgency, their willingness to risk losing a paycheck going on strike is motivated by what was said in that video by the worker: the schedule of an IATSE member. Specifically, they’re concerned with what’s called turnaround times, which is the minimum amount of time a worker has from when she leaves work to when she is expected to be back. IATSE has secured 10-hour turnarounds in this tentative agreement, which is progress for some members who had nine hours, but many members already had 10. And it’s important to remember that in this industry, 12- and 14-hour days are the norm, but 18-, even 20-hour days are not unheard of. So it’s really important that workers have the time to commute home, to eat, to spend time with families and to get a good night’s sleep, before having to commute back to work. So, workers are saying, “You know what? I’ve had 10 hours. It’s not enough. We want 12.”

You know, the other thing people should keep in mind here is that the agreement is called tentative for a reason, right? Unions are democratic institutions, and it’s up to the membership to decide whether they’re going to ratify that agreement. These are definitely members who have concerns around other things, like funding for pensions. The raises you mentioned for many members are only 3% a year, whereas currently inflation is 5%, though for the lowest-paid IATSE members, they’ve gotten a very significant raise. So, you know, this is a story to keep an eye on, right? The vote is not happening tomorrow. Members have to see the full details of the agreement, and then they’ll vote on it and discuss it amongst each other.

So, as you said, though, there’s a broader moment going on right now. There’s the strike at John Deere, and you’re going to have a worker on who’s on strike. That’s great. And there, too, the workers, you know, rejected this contract, this tentative agreement, overwhelmingly, because Deere has seen immense profits, most profitable year on record. Their CEO got a 160% raise. And meanwhile, John Deere presented the workers with the ultimatum that they would have to actually accept concessions. So, John Deere asked them — told them that new hires would not have pensions anymore.

And so, again, you know, these are illustrative of a moment where workers are willing to fight back, right? They understand they have more leverage right now. The labor market is tighter than usual. It’s harder to replace them if they go on strike. And they’re not willing to accept bad deals. And where they already have bad deals, if they’re in unions, they’re willing to try to fight to get what they’ve given up before back.

That said, there’s a —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And —

ALEX PRESS: — flip side to that, which is — oh?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, I’m sorry, Alex, I wanted to ask you about the impact of the relative newcomers to the industry, to the film and video industry. I’m talking about — it used to be just the old Hollywood studios, but now we have these giant digital companies — Netflix, Amazon and Apple — that are pouring billions into the production of content. How have these new forces affected the labor conditions? Obviously there are more workers, but how have they affected the overall labor conditions of the industry?

ALEX PRESS: Yeah, so, it’s a couple things. First, they’ve sort of sped up the amount of work that’s happening, right? So, everyone knows that plenty of people during the pandemic were at home binging Netflix, right? These streamers, as they’re called, these streaming platforms, just have an immense amount of demand for content. They’re trying to churn it out. And that then is translated to the workers themselves, who are constantly sort of being moved from project to project.

And importantly, the way that it is allowed for them to have worse working conditions, to be sped up, as it were, as we might say in the labor movement, is that these companies have different agreements with IATSE. In 2009, they struck a deal with IATSE when these were still experiments, right? Netflix was just barely out of the time of being something that was mailing you a DVD at home, right? So, these were not the enormous behemoths they are now. And there was an agreement struck that said workers would need to be more flexible here. I think the wording was that these are uncertain economies. And so, that deal was agreed upon, that said — also in that agreement, said when things have changed, if these companies prove profitable, both parties will recognize that, and this agreement will change, right? And so, there’s been this demand from the workers that — it’s obviously the time is up. These are now the dominant players in the industry. I mean, Amazon, Netflix, these are the new power. And so it really doesn’t make a lot of sense for them to be able to not contribute as much to pensions, to pay workers less, things like that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, and, generally speaking, there’s been a lot of talk about the labor shortage right now, the increased leverage that workers, whether they’re unionized or not, have in demanding better conditions. But there’s also been — there was an article in today’s New York Times talking about the number of workers who, as a result of the pandemic, no longer feel they need to be chained to a 9-to-5 job. Could you talk about how the labor movement itself is being transformed as a result of the pandemic?

ALEX PRESS: Yeah, absolutely. So, we see this reflected — right? — even among nonunion workers, in what people are calling the “Great Resignation.” So, the numbers came out from the Department of Labor recently that showed that in August almost 3% of the U.S. workforce quit their jobs, so about 4 million or so workers, which is an enormous number of people who are saying, “You know what? I’m sick of this. I’m leaving.” A lot of those workers are trying to switch industries. A lot of them are finding better deals, or trying to. They’re trying to navigate the labor market themselves.

But it really reflects a sort of reevaluation of priorities, right? I mean, workers I speak to all the time, across various industries, say that their experience during the pandemic showed them that it’s not worth it to risk your life and the health of your family for a job, for an employer who doesn’t treat you well, who might be willing to kill you, who might not take the right protections that you need to protect yourself from COVID. And so, workers have said — especially, I mean, IATSE is a great example of this, but also those workers in the food manufacturing sector who have been on strike because they were being worked 80 hours a week. They said, “You know what? A good life consists of family, of free time, of pleasure. It does not just consist of work. And if that’s not a deal that’s on offer, I’m not keeping this job anymore.”

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break. Alex, we want you to stay with us, though, as we look — speak with a worker at John Deere on the picket line and also go right here to New York to speak with one of the main organizers of the taxi workers, who, well, are facing an increasing number of suicides, dealing with massive debt, costly medallions, as they try to compete with companies like Uber and Lyft and deal with New York City. Stay with us.

Media Options