Guests

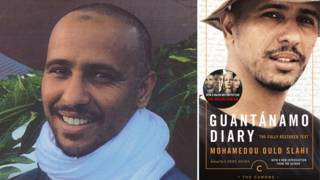

- Mansoor Adayfiformer Guantánamo Bay detainee who was held at the military prison for 14 years without charge.

We speak with Mansoor Adayfi, a former Guantánamo Bay detainee who was held at the military prison for 14 years without charge, an ordeal he details in his new memoir, “Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo.” Adayfi was 18 when he left his home in Yemen to do research in Afghanistan, where he was kidnapped by Afghan warlords, then sold to the CIA after the 9/11 attacks. Adayfi describes being brutally tortured in Afghanistan before he was transported to Guantánamo in 2002, where he became known as Detainee #441 and survived years of abuse. Adayfi was released against his will to Serbia in 2016 and now works as the Guantánamo Project coordinator at CAGE, an organization that advocates on behalf of victims of the war on terror. “The purpose of Guantánamo wasn’t about making Americans safe,” says Adayfi, who describes the facility as a “black hole” with no legal protections. “The system was designed to strip us of who we are. Even our names were taken.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today we spend the hour with Mansoor Adayfi. At the age of 18, he left his home in Yemen to do research in Afghanistan. Shortly before he was scheduled to return home, he was kidnapped by Afghan warlords and sold to the CIA after the September 11th attacks. He was jailed and tortured in Afghanistan, then transported to the U.S. military prison at Guantánamo in 2002, where he was held without charge for 14 years, many of those years in solitary confinement. Mansoor became known as Detainee 441. In 2016, he was released against his will to Serbia, which he compares to Guantánamo 2.0. By the time Mansoor was released, he had spent more than half his life in prison.

Mansoor Adayfi has just published a memoir titled Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. I spoke to him Friday from his home in Belgrade. I began by asking him to talk about how he ended up at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: OK, let’s fly back like 38 years, which, actually, I — like, when people ask me, “How old are you?” I say I’m like 24, because I don’t count Guantánamo, like try to cheat. Anyway, I born in a tiny village in Yemen, Raymah, born like with 11, 12 — 11 brothers and sisters, large family, very conservative family. I studied my primary school and secondary school in the village. We had no high school, so I had to go live with my aunt in the capital, Sana’a, which was like a new world.

When I finished with my high school, I was assigned to do some research in Afghanistan. I was like a research assistant in Afghanistan. This is how my journey started there. In Afghanistan, I spent a couple months researching and doing some of the research required to be done.

One day, after 9/11, I was kidnapped by the warlords. They were actually interested in the car; they weren’t interested in us. Then, when Americans came, the American airplane, they were throwing a lot of flyers offering a large bounty of money, which could change Afghanis’ life. So, Afghanis found out that the more you give them high-rank people, the more you get paid. The price ranged between $5,000 to like $200,000, $500,000.

First of all, we were taken as — held for ransom. Then I was sold to the CIA as an al-Qaeda general, middle-age Egyptian, you know, a 9/11 insider. I was taken to the black site, where I was, like, tortured for like over two months, then from the black site to Kandahar detention — was one of the funny things.

When I arrived at Kandahar detention, I was totally naked there. It’s like another — it’s a long journey. Second day of my arrival, guards came to move me to a tent. After the interrogation, I was asked to sign a paper that the Americans have a right to shoot me and kill me if I try to escape. I said, “No, I’m not going to sign. Of course I will try to escape. I shouldn’t be here in the first place.” So, yeah, I was beating — I refused to sign. They put my hand on the paper; they signed it themselves. I said, “No, that doesn’t count. I have to sign with my — like, willingly.”

AMY GOODMAN: And when you talked about a bounty being paid to the warlords who handed you over to the U.S. CIA and then you were tortured at a black site, do you know where that black site was? And when you say “tortured,” what actually happened to you in that two-month period? If I — I hate to bring you back there, but what actually happened?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, I don’t know where — until that day, I don’t know where the black site is, where that place. But I was kept, before that, at one of the warlord home. I was treated like a guest, teaching his kids classes — math, Qur’an and so on. And after that, I was — when the Americans came, they stripped naked. They put me in the bag, hooded, and they shipped me to somewhere I don’t know, ’til that day.

So, in the black site, it was one of the worst experiences in my life. Sometimes I’m afraid to get back there, because — not because fear. It’s just, you know, to relive that trauma, because there was no limit to whatever they can do to us, 24 hours.

AMY GOODMAN: And these were U.S. soldiers?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes, U.S. soldiers and with also Afghanis, where people actually lost their life there, because they were looking for Osama bin Laden, where is Mullah Mohammed Omar, where are the new attacks, the sleeper cells. And they have a long list and photos and all kind of things.

So, yes, I mean, those black sites, I believe no one knows how many people in that ended there and how many people actually died there. But there was no limitation to whatever they can do to you. I mean, we spent — hang on the ceiling all the time, upside down, even blindfolded, naked. The food and drink, just pour rice and water in our mouth. Sometimes they — we also do our thing sort of standing, and there’s no rest. Twenty-four hours, there’s a programming, like sleep deprivation. We have only sleep — they give you 30 minutes, like, then six hours, then 20 minutes, if you can sleep — loud music, beating, waterboarding. They used to put us in kind of like a barrel and roll it in the ice and shoot. And the first time I did, I thought that I died, because they rolled it, and they shot with a gun. I, like, was looking: “Where are the holes?” But I was still alive. So, yes, I mean —

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you were taken from there to Kandahar, and then you were held where in Kandahar before being brought to Guantánamo?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I think, Kandahar, we were at the airport. They have a detention — they built a detention prison in Kandahar. It was tents surrounded with like high walls of barbed wires. We could see the airplanes taking off every time.

So, when we saw — when we used to see the small airplanes, we knew they bring a new group of people. But we called — the big one, we called “the beast,” the Air Force really big one. So, that, when it comes, we all, like, panic, because we knew some people was going to leave, and they’re going to disappear. So, even that trauma, just waiting for your name or number to be — no, name — our name to be called.

They took us. And they call it a process station. Or they just drag me to that place, hang on the pole, strip naked, shaved. And there were all kind of humiliation, I mean, just too much to talk about it. So, we were packed on orange jumpsuits. Everything was orange — shoes, socks, uniform, shirt, T-shirt, pants. Everything was orange. And they have also goggles, ear muffs. My mouth was duct-taped, my eyes, too, also then hood. And they put one more thing upon me special, because as a big fish: They put a sign around my neck which said, “Beat me.” So, every 15, 10 minutes, I get beaten all the way for the next over 40 hours, until we arrived at Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did they say you did? What were the charges against you?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, at the black site, I was accused to be an Egyptian. They asked me I was in Nairobi and was recruiting, money laundering, I was al-Qaeda camp — head of the camp, trainer, a commander — all kind of accusations. I tried to deny them, but I admit to everything, you know? But the problem was with the details. I couldn’t give them the details. By the end, like two months and a half, when they found out I wasn’t that person, they just throw me in Kandahar detention. And from Kandahar, the same files were sent with me, where the interrogation started again about the same person, and in Guantánamo over and over and over again.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, I want to just be very clear: You were 18 years old.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, I turned — I was 18 years old when I was kidnapped. I turned 19 in the black site.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi. We’ll be back with him in 30 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our conversation with Mansoor Adayfi. He was imprisoned by the United States at Guantánamo for 14 years. He’s author of the new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: What people — most people don’t know about the purpose of Guantánamo. Let me, like, talk just a little. Guantánamo, as you know, it was outside of the law. They call it the island outside of the law. So, the purpose of Guantánamo wasn’t about making Americans safe or about safety or security. You know, it wasn’t that purpose. So, we were called detainees. And as you know, international law doesn’t apply. The Geneva Convention doesn’t apply. American law doesn’t apply. Cuban law doesn’t apply. Nothing applied at that place. It’s just a dark hole, a black site within the military base.

So, when General Miller arrived by the end of 2002, he’s the first one who wrote the camp SOP, standard operation procedure, and he was the first one who started developing what they call enhanced interrogation technique, enhanced torture technique. So, we were kept in solitary confinement, experimented on, punished, everything utilized as experiment — our religion, our daily life, food, clothes, medicine, talk, air. Everything was used in those experiments. Also, there was a psychologist who supervised those experiments.

You know, there was around — as you know, around 800 detainees from 50 nationalities, 20 languages spoken. You know, Amy, the youngest detainee was only 3 months old. They brought him with his father. He was kept in the hospital. The oldest detainee was 105 years old. That man was my neighbor. And that’s what hurt me most at Guantánamo, seeing that man, at that age, treated like the same I was treated. I couldn’t take it. I had to fight every day with the guards to stop treating that way.

So, yes, General Miller was — his job — there is research called “Guantánamo: America’s Battle Lab,” talk about how Guantánamo was turned into experimenting lab on detainees. So, even not just us, there is a chaplain I think you know about, James Yee. I met him in Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: James Yee —

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — was the chaplain at Guantánamo who would come out and talk about what happened there.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: No, before, what happened to James Yee at Guantánamo shocked and surprised us all. I remember, the first time I talked to James Yee, I was taken to the interrogation room, stripped naked, and they put me in a — we call it the satanic room, where they have like stars, signs, candles, a crazy guy come in like white crazy clothes reciting something. So, they also used to throw the Holy Qur’an on the ground, and, you know, they tried to pressure us to — you know, like, they were experimenting, basically. When I met James Yee, I told him, “Look, that won’t happen with us that way.”

James Yee tried to — he was protesting against the torture at Guantánamo. General Miller, the one who was actually developing enhanced interrogation technique, enhanced torture technique, saw that James Yee, as a chaplain, is going to be a problem. So he was accused as sympathizer with terrorists. He was arrested, detained and interrogated. This is American Army captain, a graduate of West Point University, came to serve at Guantánamo to serve his own country, was — because of Muslim background, he was accused of terrorism and was detained and imprisoned. This is this American guy. Imagine what would happen to us at that place.

So, when they took James Yee, we protested. We asked to bring him back, because the lawyers told us what happened for him after like one year. We wrote letters to the camp administration, to the White House, to the Security Council, to the United Nations — to everyone, basically.

AMY GOODMAN: When you talked about General Miller, just for people who might not remember, he, who oversaw the enhanced interrogation techniques — that was the euphemism for torture at Guantánamo — then brought from there to Iraq to Gitmoize Abu Ghraib there, to bring those same torture techniques there. And when the Taguba Report came out, it cited Miller for the massive level of abuse at Abu Ghraib. So, in that period, I mean, Mansoor Adayfi, you write so powerfully about what sustained you, about the relationships you had, not only with other prisoners — or, as you say, detainees — but with guards, as well. Can you talk about that?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, let me go a little like — I’d like to make a point here. First of all, we, as prisoners, or detainees, we weren’t just the victims at Guantánamo. There are also guards and camp staff, were also victims of Guantánamo itself. You know, that war situation or condition brought us together and proved that we’re all human and we share the same humanity, first.

Also, Amy, a simple question: What makes a human as a human, make Amy as Amy, make Mansoor as Mansoor, makes the guys in there as individual and person, you know? What makes you as a human, and uniquely, is your name, your language, your faith, your morals, your ethics, your memories, your relationships, your knowledge, your experience, basically, your family, also what makes a person as a person.

At Guantánamo, when you arrive there, imagine, the system was designed to strip us of who we are. You know, even our names was taken. We became numbers. You’re not allowed to practice religion. You are not allowed to talk. You’re not allowed to have relationships. So, to the extent we thought, if they were able to control our thought, they would have done it.

So, we arrived at Guantánamo. One of the things people still don’t know about Guantánamo, we had no shared life before Guantánamo. Everything was different, was new and unknown and scary unknown, you know? So, we started developing some kind of relationship with each other at Guantánamo between — among us, like prisoners or brothers, and with the guards, too, because when guards came to work at Guantánamo, they became part of our life, part of our memories. That will never go away. The same thing, we become part of their life, become memories.

Before the guards arrived at Guantánamo, they were told — some of them were taken to the 9/11 site, ground zero, and they were told the one who has done this are in Guantánamo. Imagine, when they arrive at Guantánamo, they came with a lot of hate and courage and revenge.

But when they live with us and watch us every day eat, drink, sleep, get beaten, get sick, screaming, yelling, interrogated, torture, you know, also they are humans. You know, the camp administration, they cannot lie to them forever. So the guards also, when they lived with us, they found out that they are not the men we were told they’re about. Some of them, you know, were apologizing to us. Some of them, we formed strong friendships with them. Some of them converted to Islam.

The military rules is cruel. And they treat those guards as a product, not humans, you know? Even those guards, when they — some of them went to tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. When they came back, we saw how they changed. When I grew up and became my thirties, when they used to bring younger guards, I looked at them as like younger brothers and sisters, and always told them, like, “Please, get out of the military, because it’s going to devastate you. I have seen many people change.”

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, this is such an important point you’re making. You were there when you were 19, and you were still there in your thirties. And then the young people who were there, who were the guards, are the age you were when you first got there.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, I mean, because I have — when I grew up at that place, when I saw how the guards came back, many of them were mentally devastated. You know, when you see a broken soul, it is painful than anything. You know, even the pain that touch your soul, it is worse than — it’s the most severe pain. I have experienced many pain — beating, torture, you name it. But the worst thing I experienced, them that touched my soul.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about the hunger strikes. You participated in these for years, and you were force-fed.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, we were in a place we tried to survive. As I told you, we had only each other. And there is no way — we tried to stop the torture, the abuses, the mistreatment. You know, we tried to find why we were held there and what was going to happen to us. So, when the first time, at Camp X-Ray, when they — they were harsh, stopping us from praying together. One day, they came. One of the brothers were praying. They opened his door. They beat him, and they threw the holy book onto the floor.

So, we — you know, this is the first protest together. So, we discussed amongst ourselves: What should we do? You know, OK, the first time I heard about the hunger strike — I never heard about it before — we went on hunger strike. It was — I spent nine days. It was a mean trying to survive, a mean — we were hurting ourselves. I always tell the people, you know, our bodies was the battlefield, because Americans torture us, abuse us and beat us on our bodies; also, we were torturing our bodies by hunger strike, by trying to resist. And I wrote about it, the hunger strikes. It was a slow journey to death, toward death. That’s hunger strike, you know?

They also become very experienced how to break the hunger strike. We spent almost — every year we had, like, to go through many hunger strikes, over and over, over and over again. We were force-fed in 2005, ’07, 2010, ’13. Some of the brothers, I spent — some of the brothers spent three years, five years, 10 years, 15 years. There are brothers ’til now force-feeding ’til that day.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was that force-feeding? Can you describe it? I remember, I mean, we’re just learning — we were just learning about what was happening at Guantánamo at the time, the tubes that were used, how big they were, that this was used as a form of torture, as well. What it meant when they were forced to stop force-feeding you?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, like as I told you, they were also — the doctors, they were experimenting on us. They used to bring — they tried to bring the hunger strike — I was one of the very first five detainees who was on the brink of death in 2005, before they approved the force-feeding. I remember when the camp commander came. He said, “Now the Congress approved the force-feeding.” When they took us, they bring tubes they took through our nose — our noses, like a drill, bleeding.

AMY GOODMAN: Through your nose.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, through our noses to our stomach. At that time, we were in bed, you know? Then the situation got worse. They brought something called feeding chair, force-feeding chair, which, like, they tie our heads — eight points — our shoulders, our wrists, our waist, our legs on the force-feeding chair. Then they brought also really large — they call it 9 French tube, really, really large, and they put it through our nose. We were screaming, shouting. But “Eat!” That way. “Eat!”

In 2005, they forced all of us to stop the hunger strike. What they did, they used to force-feed us — regularly, they should for us twice a day, but when they wanted to break the first, the hunger strike, they used to feed us five times a day. Nobody could last. The tubers, they used to bring piles of Ensure and just pour in our stomach, one after another, one after another. If we throw up, it doesn’t matter. “Eat!” Eight hours to 12 hours in the force-feeding chair. They used to bring those —

AMY GOODMAN: This is to put the Ensure through your nose.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes. You know, during — they used to pour the Ensure, one can. After we was to throw up — if you threw up, you would get more. They also used to mix some laxatives in the Ensure. We [bleep] on ourselves on the feeding chair. And we were taken to solitary confinement, really cold AC.

They said — I remember that time there’s a general who came. He said, “I was sent by the White House just to break your hunger strike.” The first time he met me, he said — he took my file — “Sir, 441” — he was so mean. Like, you can see in his eyes and words. He said, “I am here today to tell you, sir, eat. Because tomorrow there will be no talking.” I tried to explain to him why we were on a hunger strike. He said, like, “I don’t give a [bleep] about anything. Eat. Tomorrow, there will be no talking.” I didn’t last for two days. I stopped. I couldn’t take it. You know, it was too much.

In 2007, again, I went on hunger strike. Then I spent from 2007 to 2010 on force-feeding until things changed in the camp. And even, Amy, our hunger strike was viewed by the camp administration as a jihad. They said we are an al-Qaeda cell and launching jihad against the United States — the way how they understood our protest and hunger strike. And we told them, “This is our demand. You know, stop the torture, stop the interrogation, improve the living condition. And we need to figure out what’s going to happen to us.”

So, what they did, they used to also hide us when the ICRC came. I remember one day I was on force-feeding. The ICRC, his name Hatim, Sudani guy, he walked in the block and was like — on the force-feeding, I called him, “Hatim! Hatim!” He looked at me, and he covered his eyes. I said, “What’s wrong with you?” He said, “We are not allowed to see you in that way.” Even the ICRC at Guantánamo, you know, we asked them to leave many, many years. We boycott them. We give them official letters. We signed many letters asking them to leave Guantánamo, because being at Guantánamo as ICRC, it just give legitimacy to whatever Americans do here.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Mansoor Adayfi. He was Detainee 441 at Guantánamo, imprisoned without charge for 14 years and has written a memoir about his life, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. So, I then want to ask you about what happened in 2016; why, after 14 years without charge, in at 19 years old, now in your thirties, you were released; and how you ended up, a Yemeni man, in Serbia.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I refused to come to Serbia. I was forced. They told me, “You have no choice. Either leave or rot in here.” Then, the ICRC, when I protest — I went on hunger strike protesting going to Serbia. The ICRC came, [inaudible]. They issued a new — Obama administration issued new rules: If any detainee accepted by any country, he will be forced to leave regardless. So, basically, I had no choice. They bought me with money, and they gave the Serbian government money to take me again. So, this is the game. We have no say.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you end up in Serbia. You end up in Belgrade. I was just listening to an interview that Frontline did with you. And when PBS partnered with NPR to do this documentary series, you did an interview with them. And ultimately, you were beaten for that interview. Can you explain what happened to you? This, not long after you got to Serbia.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, when they came to interview me, I was on hunger strike on my 25 days. I spent 48 days on hunger strike protesting my condition, because the agreement between the United States government and the receiving countries, it was a resettlement agreement, but when you arrived at the hosting countries, they said, “No, we had an agreement. We had a new contract to come here for two years. You’ll live in our countries under restrictions. Nothing. You have no education, no courses, no, no, no, no.” You know, they made us promises, especially in my case. I was recommendation to finish my college education. So I talked to my lawyer. I said, “I cannot live here. I cannot stay here. I want to leave.” So I went on hunger strike. When I was — even one of the universities, I was accepted. When they found out I came from Guantánamo, I was expelled. You know, this is one of the things that hurt me most after Guantánamo. So, I went on hunger strike.

When the Frontline came here, the first, we had — they went to the government. They said they were fine, and they were doing well. When they came to see me, I was on hunger strike. They were surprised. The first time, we had an interview. Then, the second day, some people came to my apartment, took me down. They would send me messages: “Stop lying. You are lying. You’re a liar. You’re a liar.” And so on. And, you know, I don’t want to cause any problem, because I didn’t know what to expect, because, as you know, the Serbians, they have their history with Bosnia in the 1990s. Scary place. So, then I disappear. Then I contact my lawyer. I contacted the Frontline, and we continue again.

And again, after the interview was aired, a Serbia newspaper really represented me in the worst way — newspaper, TV. I was arrested, interrogated, threatening to be entrapped. You know, I wrote a lot about it, and you’ll read it here. I don’t want to talk much detail this, because they’re going to kick my [bleep] again. But what I have learned at Guantánamo, I will never keep silence, you know, because keeping silence only give the oppressor a mean to oppress you more. So, I will never keep silence. Whatever they do, I will keep — you know, because I have done nothing wrong. Even if I had done something wrong, there is a justice system. You cannot just beat people, arrest them or interrogate them because you have a power.

So, basically, yes, I mean, then, in 2018, they came to me. They said, “Now with the two years finished, you have the choice: to go to Saudi jail or to go to the refugee camp.” And that guy — his name is Nikola — told me, “Americans [bleep] you. The interview cost you a lot,” literally, word by word. And my lawyer was there listening to him. He was like, “What?”

So, yes. When I talk about our life after Guantánamo, we still live in Guantánamo 2.0. You know, just to let you know, Amy, I studied in another college. I will be graduating on the 29th of December. And my thesis is about rehabilitation and reintegration of former Guantánamo detainees into social life and the labor market. I have been doing a lot of research for the last five years. I have interviewed around 150 brothers released from Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: You can’t leave Serbia, Mansoor?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You remember when I told you the worst pain that touch your soul? You know, I wanted to get married. I found really a woman that I thought she is going to be my wife. The only thing — the only thing was like the piece of paper in a travel document where I can get married. So, I couldn’t travel, so I couldn’t marry. And finished.

Not just me. I think I’m lucky. There are — one of the brothers, Lotfi, he died last year. He had heart diseases. He was relocated from Kazakhstan to Mauritania, where they didn’t have a good health system. He needed to go to somewhere where he can — he’d be treated, because he needed emergency surgery. And his doctor told him, “You have only six months.” So, he needed $30,000. CAGE organized, raised fund for him. And they said his surgery will be covered. He needed just a travel document, either to travel to Tunisia or other country, just to have the surgery and get back. He lost his life. You know, it’s one of the saddest moments. Like, when I was talking to him, [inaudible] was talking to ICRC, was talking to human rights organizations, to governments, nobody cares. Simply, nobody cares.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, jailed at Guantánamo for 14 years, never charged. We’ll be back with him in 30 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Is It for Freedom?” Sara Thomsen. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our conversation with Mansoor Adayfi, jailed by the United States at Guantánamo for 14 years, author of the new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. I asked him about reports that the Biden administration is considering holding Haitian refugees at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: They should help the countries to have some kind of stability so that people can live their lives. Yeah, it’s one of the biggest crises in the 21st century, the massive immigration of refugees. But creating Guantánamo again, if brought us again, what’s going to happen to these people? How is it going to be treated? So, I hope it’s not — honestly, I tweeted about it. And I don’t want anybody to be detained in that place, especially the name of Guantánamo. I love Guantánamo. I have made peace with it. But the idea of Guantánamo, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me ask — when you said, “I have made peace with it,” you held up your scarf, that’s orange, that’s wrapped around your neck right now as you speak to us. You were forced to wear orange from head to toe. Why wear orange now?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I wear orange all the time, because at Guantánamo, when the psychologist and the ICRC told me, “Wow! If you see the orange color, you will be be shocked, if you heard the [inaudible].” I said, “No, this is part of my life, and I will never let Guantánamo change me.” So, Alhamdulillah, I choose to fight to close Guantánamo and to try to help anyone who are wrongly detained or, you know, stripped his freedom, because I don’t want anyone to suffer the same fate I have suffered, although I have made peace with Guantánamo. I almost, like, every day talk about Guantánamo, write, talk, give interviews and so on. My other brothers, they don’t want to remember, because it’s like a trauma. It reminds yourself over and over again. But, for me, I took it in another way. And, Alhamdulillah, I have some kind of strength. Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala gives me strength. So, I would use that strength to support those helpless people and also to bring the truth about Guantánamo. So I use my 441 and my emails and my names everywhere. And I use the orange color all the time also to bring the awareness to the people the misuse of power, how can damage us as humans.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, if you can talk about how you survived through Guantánamo, what hope meant for you? And was it hope that kept you going, through the forced feedings, through the hunger strikes, through the beatings, through the torture? What got you through?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: First of all, Amy, faith as Muslims. The first thing, we stick to our faith as Muslims, because — before Guantánamo, I was studying in the Islamic Institute. That’s where I got the mission to go for research. So, most of us, even the U.S. government viewed us as terrorists, or the faith as source of terrorism. It’s not. First it’s our faith, stick to it, praise to Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala, knowing that everything in the hand of Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala, and Americans have nothing to decide our fate.

Secondly, we had each other, because we were kept at that place. We had no books, nothing, just totally disconnected from the world outside. So we had each other. I wrote about it. I wrote about it, a piece called “The Beautiful Guantánamo,” which is, I just took all the bad things, and I wrote about how we survived Guantánamo. Imagine, Amy, around 50 nationalities, 20 languages, different background. People who were at Guantánamo, they were artists, singers, doctors, nurses, divers, mafia, drug addicts, teachers, scholars, poets. That diversity of culture interacted with each other, melted and formed what we call Guantánamo culture, what I call “the beautiful Guantánamo.”

Imagine, I’m going to sing now two songs, please. Imagine we used to have celebrate once a week, night, to escape away pain of being in jail, try to have some kind of like — to take our minds from being in cages, torture, abuses. So, we had one night a week, in a week, to us, like in the block. So, we just started singing in Arabic, English, Pashto, Urdu, Farsi, French, all kind of languages, poets in different languages, stories. People danced, from Yemen to Saudi Arabia, to rap, to all kind. It’s like, imagine you hear in one block 48 detainees. You heard those beautiful songs in different languages. It just — it was captivating.

However, the interrogators took it as a challenge. We weren’t challenging them. We were just trying to survive. This was a way of surviving, because we had only each other. The things we brought with us at Guantánamo, whether our faith, whether our knowledge, our memories, our emotions, our relationships, who we are, helped us to survive. We had only each other.

Also, the guard was part of survival, because they play a role in that by helping someone held sometimes and singing with us sometimes. Also, we also had the art classes. I think you heard about the — especially in that time when we get access to classes, we paint. So, those things helped us to survive at that place.

Hope also. Hope, it was a matter of life or death. You know, you have to keep hoping. You know, that place was designed just to take your hope away, so you can see the only hope is through the interrogators, through Americans. We said, “No, it’s not going to happen that way.” So we had to support each other, try to stay alive.

Also, we lost some brothers. And I lost very good brothers in that place. It’s one of the hardest and saddest moments at Guantánamo.

And, hamdulillah, I managed — I don’t know if I survived, to be honest with you, because someone asked me last month — I had an interview with the — I had an interview last month. Someone asked me, “How did you spend your twenties and thirties?” I said, “I don’t know.” I didn’t know what this means, twenties or thirties. I am now at my late of my thirties, but I’m not sure yet. So, imagine I have a huge gap in our life, like 15 years ago until now five years now. And physically, you know, technically, practically — you know, technically, I feel like I’m 30, 38, 39, but, practically, I feel like I’m still in my twenties, this mentality. Even you can see in my behavior, the way I talk, the way — that’s who I am, actually. So we have this huge gap.

And when I was released, different society, language, community. Anyone I get to interact or friend with get arrested, interrogated. People stay away from us, because the stigma of Guantánamo. So, basically, but I’m trying now — I’m trying to make a life, to get married. Yeah, I can sing a song for you.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, you said you’d sing two.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah. The first one, when we, like, supporting, because, especially when General Miller arrived, he tried to crush us. The first day he arrived, he searched all of us, beat all of us, cavity search. You know, they put dogs, FC teams, pepper spray. It was like a message: “I am here. [bleep] those terrorists. I’m going to kick your [bleep].”

But at Guantánamo, we don’t treat people wrong. It doesn’t matter. The only thing we have with guards is respect for respect and [bleep] for [bleep]. It’s as simple as that. Not all of us, but a group of us. I am sorry for these words, but we are talking about Guantánamo.

So, because Guantánamo is designed to extract the worst of us, so when someone was to go to the interrogation or for torture, we tried to support him, you know, and we would sing for him. [singing in Arabic] And like around 48 — two blocks sometimes sing together collectively. It was like [inaudible] encouraging. It means —

AMY GOODMAN: And what did it mean? What did that mean?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: [speaking in Arabic] “Go, go with peace. May Allah grant you more peace and safety.” And when they came from appointment or interrogation or torture, or people can arrive at Guantánamo, new at Guantánamo, especially when a new group arrived at Guantánamo, we would say — we would welcome them, that songs. Imagine, you just new arrive at Guantánamo, and three blocks, around 150 detainees, sung for you. [singing in Arabic] It means, “Welcome, welcome, they who come.” Imagine when the brothers first time arrived, you sing for them. You know, it was like they were surprised. “Are they detainees, or they’re like living in kind of like kind of a beach, laying or something?” One of the brothers used to tell us, “We thought that you guys live in some kind of like lovely life, enjoying yourself.” Then, when they took the hood, “Whoa! It is cages.” I said, “What did you expect?” He said, “I heard the voice. I thought, like, everyone is happy, singing.” So, we can, like, give them the first impression that everything is OK.

AMY GOODMAN: Mansoor, last two questions. One is, you talked about the art classes that you took. Can you describe what art meant for you? And what did you create? What did you draw?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, when we started negotiating with the camp administration in 2010, when we negotiated in 2009 and '10, we negotiated an art class. The camp commander said, “Art class? You guys are terrorists. You don't know how to paint.” So, we asked the brothers, “Can you paint, please?” The second meeting, we showed them. They were shocked and surprised. They said, “OK.” It was a process, the negotiation, asking over and over again.

But, Alhamdulillah, art class was one of the most important classes at Guantánamo, because it helped us to express ourselves. It was a mean, a way of escaping being in jail, because you need to escape that feeling. So, art connect us to the world outside. You can see the brothers. We paint sea, trees, the things we missed most, sky, the stars, you know, homes, deserts and so on. So, arts actually help us to connect to our life that we almost forgot. The art connected us to ourselves, because it brung that memories back. It connected us to each other.

It connected us to the guards. You know, when someone saw arts, it can, like, mutual admiration and love for arts. And some of the guards asked for the brothers to paint for them. They will give them like arts for gifts. Brothers used to teach guards arts. Same thing, guards who has background teach brothers.

Also, you know, in the arts, one of the brothers, Sabry, one of the artists [inaudible], he said, “Mansoor, wa alallahi, when I paint, I saw myself in that painting, like on the hill, on the boat, on the ship, on the sea, sometimes like running here and there.” So, he said, like, “It just takes my mind and calm people down.” And, you know, it was like a therapy, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Mansoor, I wanted to ask you about your choice to have a woman voice your book. Usually, it’s the author, when a book is done through audio, that someone can listen to it. It’s either the author or an actor. But you chose to have a woman read, voice Don’t Forget Us Here. Why?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah. I remember, like, talking to Sam from Hachette — hi, Sam — Antonio and Julia, my agent. I said, “Guys, I need a woman — I want a woman to read my book.” “No, why? It doesn’t happen before. You know, typically, the man” — I said, “No, I want a woman to read my book.” “Mansoor, that doesn’t make any sense.” I said, “What makes sense about Guantánamo [inaudible] happened to us, you know? Men have been kidnapping me, torturing me, kicked my [bleep], imprisoned me. And, like, they have done a lot of things, you know? The one who treated us nicely was women, so I want a woman to read my book. So, why not?” At the same time, I told him, it is like kind of racism against women. So, first they send me some kind of like men. I said, “No, I don’t want. I want a woman to read my book.” So, when they found it turned out good, they said, “Well, it was a good idea.” I said, “I know. I told you.”

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, speaking from Belgrade, Serbia. He spent more than 14 years at Guantánamo, never charged. He just wrote his memoir. It’s called Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. He now works at CAGE, an organization that advocates on behalf of victims of the so-called war on terror.

That does it for our show. Special thanks to Mike Burke and Hany Massoud. I’m Amy Goodman. Stay safe.

Media Options