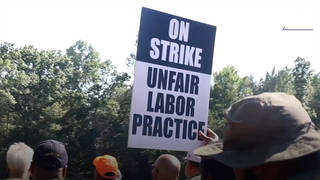

In Alabama, hundreds of striking miners are set to return to work Thursday after nearly two years spent on picket lines in the so-called right-to-work state. This was the longest strike in Alabama history. Its end comes after the Warrior Met Coal company successfully used replacement workers to keep its mines running, reporting large profits to shareholders due to the skyrocketing price of coal. At the same time, the company told miners they would only retain their jobs if they agreed to a 20% pay cut and to relinquish various benefits relating to weekend pay and healthcare. We go to Birmingham, Alabama, for an update from independent labor journalist Kim Kelly, who has covered the Warrior Met strike since it began and says many of the workers felt abandoned.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, as we end today’s show in Alabama, where hundreds of striking miners are set to return to work Thursday at the Warrior Met Coal company after nearly two years on the picket line. The president of the United Mine Workers of America sent a letter to Warrior Met granting an unconditional offer to return to work on March 2nd as the two parties continue to negotiate a new contract.

For more on the end of the longest strike in the history of Alabama, a so-called right-to-work state with powerful anti-union laws, we’re joined in Birmingham by Kim Kelly, independent labor journalist who has covered the Warrior Met strike since it began. Her new piece for The Nation magazine is headlined “Why the Warrior Met Strike Is Ending.” She’s also author of the book Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Kim. It’s great to have you with us. Explain what’s happening tomorrow and the significance of this longest strike in Alabama history.

KIM KELLY: Thank you so much for having me and for spotlighting these workers’ struggle. It’s been difficult to get media attention on this strike.

But, yes, after 23 months, the coal miners of Brookwood, Alabama, are heading back to work. Now, March 2nd is the return-to-work date that President Cecil Roberts gave. It’s going to be a long process, though. The company — I acquired a document from the company that expressed some of the conditions that it had for the workers to return. It wants them to get physicals and drug tests and undergo safety training. So it’s not going to all happen at once. Not everyone is going to roll down into the mines tomorrow. But the process has begun.

And this is in kind of a messy end to what’s been a very long and grueling and difficult labor conflict down here in — outside Birmingham, Alabama. These miners went on strike back on April 1st, 2021. They voted down a tentative agreement that was reached a few days later. I believe that was April 8th or 9th. And they’ve been out on strike ever since. It has been a slog. But these miners have held the line. You know, they’ve been supported by their families, by the local community. It’s been incredibly difficult, because, as you mentioned, Alabama is a right-to-work state. This is not a union-friendly area. The local judiciary has made it incredibly difficult for them to hold their pickets and to continue the strike. Local law enforcement has made it very clear they are not on the workers’ side. The company has been very recalcitrant in the way that it’s dealt with the strike.

But after 23 months, the decision was made by UMWA leadership that, you know, they had to try a new tactic. The company has not been budging. The company has actually been profiting, even with the skeleton crew of scabs it has been operating with, due to high coal prices. So, it’s really at kind of a do-or-die point. As President Roberts mentioned in the letter he sent to Warrior Met’s CEO, the only people being harmed right now are the miners and their families. And so the union has changed tack, and the strike itself is no longer happening, but the fight continues. They’re going to keep fighting out this struggle in negotiations at the bargaining table. And hopefully, we’re going to finally see some movement, because these miners really need a break right now.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk about the company’s use of replacement workers and the impact that that had in their ability to persevere against the union in this case?

KIM KELLY: Absolutely. One of the reasons that Warrior Met Coal has been able to remain profitable and productive is the fact that it launched an extensive effort to recruit replacement workers — scabs — from other states. We’ve seen billboards as far as West Virginia and Kentucky, Tennessee, asking workers, “Come down here. Come work for us. We’ll give you benefits. We’ll give you bonuses.” The people working in the mines right now, who are not union, who are replacement workers, they’re making $2,000-a-month bonuses, that the workers whose jobs those rightfully are were never making. And it’s a problem, because these workers, they don’t have the experience and the knowledge that the union miners have. You know, some of these folks are new to mining. They’ve worked nine months, a year. Some of the folks that are on strike, they’ve been working in those mines for 20, 30 years. That makes a difference. And the company has been able to exploit the fact that workers need to pay the bills. Coal mining is a complicated industry. There aren’t as many decent-paying jobs as there used to be. And so, people have come down from other states and, essentially, taken these Alabama workers’ jobs, crossed the picket line and helped to break the strike.

AMY GOODMAN: As you write about, Warrior Met reported large profits due to the mines running, the skyrocketing price of coal. Can you talk about not only this and what that means, but also what it means to be in Alabama, a famously anti-labor state, and what this signifies for the country right now?

KIM KELLY: So much of this is sheer bad luck. The miners walked out on April 1st. In June 2021, coal prices skyrocketed. I believe they quadrupled. And those prices have held. So, throughout the entire strike, or even though these workers have been out, they have been running a skeleton crew, the mines have not been at full capacity, the owners have been able to profit because of those coal prices. And the market is not something that workers can control. So it’s been a huge issue and a huge reason why the strike’s economic impact hasn’t been felt the way that the union and the workers wanted it to be.

And also, the fact that we are in Alabama, which I must say is a state with an incredibly rich labor history and a strong labor movement, but a very, very anti-union state government. It’s a right-to-work state, which weakens the movement. As I mentioned, law enforcement has been very clear about whose side they’re on in this conflict and have turned a blind eye to violence on the picket line. And Alabama itself — there is something that happens a lot when we talk about the Deep South, places like Alabama and Mississippi and Louisiana, where I think there’s an impulse for folks to write them off. It’s like, “OK, well, we’re not going to be able to pull anything off here anyway. There’s no point.” But there is. And there are so many people been fighting here for centuries, whether we’re talking about the mine and mill workers decades ago or the sharecroppers that Robin D. G. Kelley highlighted in his book Hammer and Hoe or the Amazon workers down the street in Bessemer two years ago that launched the first effort to unionize an Amazon warehouse in this country. There is a labor movement here. There are workers here. But they need more support. They need better laws. They need better politicians and officials to actually support them, because this shows what happens when workers are abandoned by the people that are supposed to advocate for them and supposed to protect them. They’re hung out to dry and left at the mercy of a Wall Street venture capital-backed company that sees nothing but dollar signs when it looks at them.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And we’ve only got about a minute left, but I wanted to ask you precisely about the lack of support, either focusing on this strike by the national media or national politicians, especially given the fact that the Biden administration claims to be so pro-labor. There were no major political figures coming to Alabama to walk the picket line or focus on the strike.

KIM KELLY: The workers here have felt abandoned. And basically, the issue with this strike is that these are a group of multiracial, multigender, rural, blue-collar union workers in Alabama. The Republicans know that they’re union, so they don’t care about them. And Democrats see them as a lost cause, because many of them are conservative. It’s a more culturally and politically conservative group of workers, so they think, “Oh, well, it’s not worth our time.” But they are. This should have been the biggest labor story in the country for the past two years, and it wasn’t. And I think that says a lot about the biases and prejudices and partisan nonsense that dictate whose stories get covered and whose don’t.

AMY GOODMAN: Kim, we just have 20 seconds, but the issue of conversion, moving away from coal, and how workers are included in that discussion?

KIM KELLY: Yeah, that is a big question for 20 seconds. One thing I want to mention about these workers specifically, they mine metallurgical coal, which is not involved in the energy economy. It’s used to make steel. If we went to a green economy tomorrow, these workers would still be heading down into the pits, and that coal, that Met Coal, would still be shipped overseas to industrialized countries. It’s complicated, but the thing I want to impress listeners with is that we need to look after workers even if we don’t like the jobs they’re doing. Solidarity means solidarity. And we need to work this out together as we move forward, because we can’t afford to leave people behind.

AMY GOODMAN: Kim Kelly, we want to thank you so much for being with us, independent labor journalist. We’re going to link to your piece in The Nation, “Why the Warrior Met Strike Is Ending.” Her book, Fight Like Hell. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options