Guests

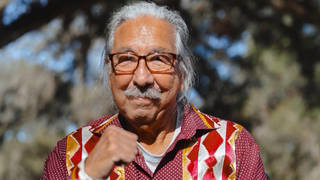

- Leonard PeltierIndigenous activist and longtime political prisoner who spent nearly 50 years behind bars over his involvement with the American Indian Movement.

Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman sat down with longtime political prisoner and Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier for his first extended television and radio broadcast interview since his release to home confinement in February. Before his commutation by former President Joe Biden, the 81-year-old Peltier spent nearly 50 years behind bars. Peltier has always maintained his innocence for the 1975 killing of two FBI officers. He is expected to serve the remainder of his life sentences under house arrest at the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Nation in Belcourt, North Dakota. In a wide-ranging conversation, we spoke to Peltier about his case, his time in prison, his childhood spent at American Indian boarding school and his later involvement in the American Indian Movement (AIM) and more. “We still have to live under that, that fear of losing our identity, losing our culture, our religion,” Peltier says about his continued commitment to Indigenous rights. “The struggle still goes on for me. I’m not going to give up.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In a Democracy Now! global TV/radio broadcast exclusive, we spend the hour with longtime Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier. In February, he was released from a federal prison in Florida after spending nearly half a century behind bars for a crime he says he did not commit. President Biden, on his last day in office, commuted Peltier’s life sentence to home confinement. Biden’s decision came after mounting calls by tribal leaders and supporters around the world in a decadeslong community-led campaign fighting for his freedom.

In the ’70s, Peltier was involved with AIM, the American Indian Movement. In 1975, two FBI agents and one young AIM activist were killed in a shootout on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Two AIM members were later arrested for killing the agents. At trial, the jury acquitted them. Leonard Peltier was arrested later, tried separately and convicted. Peltier has always maintained his innocence.

Notable supporters of Leonard Peltier over the years included Nelson Mandela, Pope Francis and Amnesty International. Supporters of Peltier say his trial was marked by gross FBI and federal prosecutorial misconduct, including the coercion of witnesses, fabricated testimony and suppressed exculpatory evidence.

After being released in February, Leonard Peltier returned home to live on the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota. September 12th was Leonard Peltier’s 81st birthday. People gathered throughout the day, visiting him to celebrate this first birthday in almost a half a century where he was home. We got there on his birthday. The next day, Saturday, we spoke in his living room in his first extended TV/radio broadcast interview since his release from prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. I’m Amy Goodman, host of Democracy Now!, in the home of Leonard Peltier, just recently freed from prison after 49 years.

LEONARD PELTIER: Plus two months.

AMY GOODMAN: Plus two months.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: I’ve spoken to you so many times, Leonard, in prison, in various prisons, several of them supermax prisons. It is quite astonishing to be here with you in person. Tell us where we are. Where are we sitting?

LEONARD PELTIER: We’re sitting in my home, that was given to me by my supporters. This was not given to me by the tribe, or the government had nothing to do with it. I was released by Biden under a commutation of my sentence and home confinement. Actually, what happened was, I was — I was taken out of one prison cell and really put into another type of prison. But this is my home now. This is my home. So it’s a million times better.

AMY GOODMAN: Wait, what do you mean when you say you were taken out of your prison cell after more than 49 years, and you’re saying that you’re not completely free?

LEONARD PELTIER: No, no, I’m on very restrictive restrictions. Even to go to the post office, I got to call my — I call her my handler. I have to call her to go to the post office. Then, when I get back, I have to call her and tell her I’m back. Or if I go anything, if I go shopping or whatever, I have to do that. If I have to go a hundred miles past the nation — I don’t call my place a “reservation,” either; we’re nations of people — I have to get a pass, usually from Washington, D.C., to go to medical, usually medical, or religious ceremonies on different nations, Indian Native nations.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s go back to that moment when you were in that prison cell in Coleman, in Florida, and you got word that President Biden had commuted your sentence. It was just hours before he was leaving office? Can you tell us about that process, how it took place?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, as I went through the years filing for pardons and stuff, Ronald Reagan was the first one to promise to leave me — pardon me. Somebody in Washington stopped it. There’s only one organization that could have stopped it, and didn’t have the power to stop it, but still, somehow, were in power, enough to where they can override a president of the United States, our Congress. It’s the FBI. And Reagan promised to let me go. And the FBI intervened, and that was stopped. And Bill Clinton and Obama, and, finally, we get to Biden.

And Biden, there was pressure put on him from all over the world. Almost every tribal nation here in the United States filed for my release, demanding my release. The United Nations — the United Nations did a full report on my case, and they demanded that I be released immediately and to be “paid,” quote-unquote. Hundreds of Congress and senators and millions of people —

AMY GOODMAN: And the pope.

LEONARD PELTIER: And the pope, two popes, the last pope and the current pope. And world leaders, many world leaders, demanded my release.

AMY GOODMAN: The Nobel Peace laureate, bishop — Archbishop Desmond Tutu?

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes. I was also nominated for — and nominated four times, because of my work from prisons, for a Nobel Prize. And the board and everything granted it, but somebody intervened again. So, four times, I lost that.

I think somebody was pushing Biden to stop any — any possibility of signing a pardon. So, he didn’t sign it until the last moment. And actually, a day and a half before he actually signed it and he was — his term was completed, I just took the position that, “Nah, he’s not going to do this.” And I just kind of laid back in my cell, and I thought to myself, “Well, I guess I die here, and this is the only ultimate sacrifice I can make, and I have to accept it. I have no other choice.”

And as I laid there and thinking about it, other people came by — even guards would tell me, “Don’t give up, Leonard. Don’t give up.” And other prisoners, and some of them prisoners were telling me that, “Leonard, he’s got to know that if he doesn’t sign this, this is political suicide for the Democratic Party, because there’s millions of people that are going to break away from this if he doesn’t.”

And so, I was laying there, and I was thinking, “Well, let’s try one more thing.” So I called a representative of mine that was working closely with the Biden administration. We got — we have Native people — we had Native people in his administration who were communicating with Biden. And I said, “Tell him to give me a commutation on my sentence and home confinement.” So, she called and did this, and that’s what I ended up with. And that’s what I’m — that’s what I’m living under right now.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you hear that you were going to be free?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, it was kind of unbelievable in the immediate moment. I thought somebody was just playing games with me. And I thought, “Ah, I’m going to wake up, and this is all a dream, and I’m in the cell, and I’ll be in there.” And I really didn’t believe it until, actually, I walked in the house here.

AMY GOODMAN: What was it like to leave Coleman?

LEONARD PELTIER: Wow! Imagine living in a cubicle larger than some people’s closets for all those years, and then you finally are able to walk out of there. I mean, it was just — for me, it was unbelievable that this was actually happening to me. But, I mean, the feeling of, wow, I can go — I’ll be home. I won’t be able to — I won’t have to go to bed in this cold cell with one blanket, and I won’t have to smell my celly going to the bathroom. I won’t have to eat cold meals. Is this really over for me? Is this really going to be over for me? And it was disbelief. A lot of it was disbelief, really.

AMY GOODMAN: And now we’re sitting here in your living room surrounded by the paintings you did in prison.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You are an artist extraordinaire, maybe about to have a gallery showing in New York. Through the years, you sold your paintings. Talk about painting in prison and how you came to be a painter.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, see, a lot of people think we were allowed to paint in our cells and stuff. We were not. We were not allowed. They had an art room, hobby craft area, and one of the — one of the hobby crafts was painting. So, you have to sign up for that. A lot of people think that all the art supplies was given to you by the prison, the hobby crafter. That’s not true, either. We have to buy our own. And I went and signed up immediately to go into the art hobby craft. And I used to go there every day, and that’s what I did. I painted and painted and painted ’til I was able to create my own style and everything, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you see your paintings now?

LEONARD PELTIER: No. Two months ago, I think now, I lost 80% of my vision. And I’m in the process of, hopefully, getting my eyesight returned, treated and returned.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re spending the hour with the Indigenous leader, longtime political prisoner, Leonard Peltier. He was released from prison after nearly 50 years behind bars. It was his birthday weekend that we sat at his home in Belcourt, North Dakota. Coming up, he talks about being put in an Indian boarding school as a child, his activism and more.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Freedom Is [Free]” by Chicano Batman, in our Democracy Now! studio. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our global TV/radio broadcast exclusive, as we sit in the home of longtime Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier in Belcourt, North Dakota, on the reservation. I spoke to him on Saturday, the day after his 81st birthday, in the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Cree Reservation. He was released in February from the federal prison in Florida after spending nearly half a century behind bars.

AMY GOODMAN: So, take us back in time. Introduce us to you, starting by saying your name, who your parents were, the nations they were a part of, your family, where you lived growing up.

LEONARD PELTIER: OK. My name is — English name is Leonard Peltier. I’m 81 years old as of yesterday. My father is a Chippewa Cree, from this reservation, this nation right here.

I keep saying “reservations,” because we was trained — we was taught from childhood that we are all reservations, we’re Indians. And we’re not Indians, and this is not a reservation. We made treaties with the United States government, and the Constitution says they shall only make treaties with sovereign nations. So we’re sovereign nations. We’re not — we’re not Indians, as they claim to be — they claim we are.

And my mother is from Fort Totten. But again, that’s not the real name. The real name is Spirit Lake, and that’s of the Lakota/Dakota people.

I was raised, majority of my life, here with my grandparents, which is usually the traditional way of my people. The grandparents will take the children and raise them. But when grandpa died, grandma had no way, no way to support us, so she went to the agency here to ask for help. And in retaliation, they took us and put us in a boarding school.

AMY GOODMAN: What boarding school?

LEONARD PELTIER: Wahpeton, North Dakota, 1953. I was there ’til — for three years, ’56. And it was extremely brutal conditions.

AMY GOODMAN: How old were you?

LEONARD PELTIER: I was 9 then, when I went. And —

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the point of these boarding schools. Was your hair cut? Did they stop you from speaking your language?

LEONARD PELTIER: Of course. They did all — they did — that was the purpose of the schools, is to take the Indian out of the Indians, is what they literally — was the order. They took us to the boarding schools. The first thing they did was cut all our — buzz cut our hair, took it all off, and then put us and took us into the shower. We showered, and we come out of the shower, and we were poured all over our bodies DDT. As you know, that’s poisonous.

AMY GOODMAN: They poured DDT over your body?

LEONARD PELTIER: They poured DDT, with all the cans, on your head, the whole body. And then they gave us — issued clothes, bedding and assigned us to a bed. And that was the beginning of our treatment. It was an extremely, extremely strict school, and beatings were regular for any little violation of those rules.

I might have been a little hot-headed, I don’t know. But when I first got there, there was a group. They called themselves the Resisters. And I immediately joined them, and I became part of the Resisters. So, we would sneak behind the gymnasium, and we would talk our language. We would sing some song, even do some prayers, yeah. And if we got caught, we got the [bleep] beat out of us.

AMY GOODMAN: You wrote in your book, Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sun Dance, that you consider these boarding schools your first imprisonment.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes, it was. Was. I found the rules more restrictive than when I went — ended up in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you go to this residential school with your cousin and sister for three years. Where do you come back to? And how did you maintain your language and your culture?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I came back here to live with my father. And they were still living in log cabins, no electricity, no running water. We had to haul water. We had to haul wood. And we only had $55 to live on, which was my father’s World War II military benefits, and that’s what we had to live on.

And we were facing the — we were facing the time of termination. The United States government wrote a bill, passed by Congress, signed by the president, of termination in 1956. It was supposed to be completed by 1985. And the first one to be terminated was the Menominee Indians of Wisconsin. They had millions of making — millions of prime land, timber and lakes to make hunting lodges and other things out there. It was beautiful, which they do today. They still — they got all those things out there today. But they came and took all that land from them. Then they come here in 1958. Was it ’58? Yeah, ’58. I was 13 years old then. And they came and told us we have been terminated, and we have to accept that. We were supposed to be the second reservation to be terminated.

AMY GOODMAN: The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Cree.

LEONARD PELTIER: Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Cree, yes. And my father and all of them and their generation, a lot of people left on relocation. They said, “It’s hopeless. We can’t fight these people. They’re too powerful. They got — they’re just too powerful. You know, maybe life will be better over there,” and stuff like this on this relocation. So they picked the city to go to. A lot of them went to Washington state and Oregon.

And it was a small group of us stayed here and said, “No, we’re not leaving.” So, my dad and his generation said, “Well, what do you mean, 'been terminated'? You can’t come here and tell us that we got to leave and you’re going to just terminate us as a race of people and tell us that we no longer exist. Go [bleep] yourself. Come on. Let’s fight it out.” And literally, they were — I was proud of them. I was 13 years old.

They stopped all provisions. One little girl died over here from malnutrition, and that’s what really got everybody angry.

AMY GOODMAN: So they thought they would starve you out.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah, they were making conditions so hard that we were accepting termination. We were leaving. A lot of people took to say, “Well, at least my kids won’t starve to death.”

AMY GOODMAN: And the BIA reversed its decision?

LEONARD PELTIER: They reversed their decision and gave us $50 —

AMY GOODMAN: Vouchers?

LEONARD PELTIER: Vouchers to go buy groceries here in Rolla. Everybody got — the whole reservation got $50.

AMY GOODMAN: And they didn’t disband the reservation?

LEONARD PELTIER: No, they got the hell out of here, because we told them we’re going to fight them.

AMY GOODMAN: So, this was really the beginning of the Red Power Movement and the founding of AIM, right?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I guess so, in so many — yeah, in so many — yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The American Indian Movement.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Which you want to rename the American —

LEONARD PELTIER: But they were — but they were doing that for — I mean, my people have been fighting back for 500 years, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: But the modern day.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah, the modern-day stuff. But no, we went to war with them. We went to all kinds of different levels of —

AMY GOODMAN: Resistance?

LEONARD PELTIER: Resistance, you know.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the founding of AIM, the American Indian Movement, which you today would like to rename the American Indigenous Movement.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I was involved in a number of different organizations before I joined AIM. And one of the biggest ones that I was — I helped organize the United Tribes of All Indians in Washington state. And we took over Fort Lawton. One of the treaties that we were pushing them days — actually, our people was — older people were pushing this, too, but they just passed. All of our knowledge came from traditionalists. That’s the policies, the American Indian Movement, we followed there. There.

First of all, people got to understand, the American Indian Movement policy is they can’t come onto this reservation, start dictating their policy. They have to be invited by the traditionalists or a tribal government or what else. We can’t just go onto a reservation and say, “You’re going to do this, you’re going to do that.” No, we can’t do that, and we don’t do that. We have to be invited first.

So, anyway, this was before I joined the American Indian Movement. I was involved with the fishing and hunting struggles over there. That was a big area that they really fought hard and got really —

AMY GOODMAN: Fishing and hunting rights.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes, treaty rights. In fact, Marlon Brando got arrested with us in 1955. He got arrested on one of them lakes. I wasn’t there, but he was — he got arrested fishing and hunting with the Natives out there.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the occupation of the BIA offices in Washington, moving on to Wounded Knee and Pine Ridge.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, it just — our resistance became extremely popular. American Indian Movement was growing, and not just here in America — Canada, Central America. Said, “Wow! There are a lot of full bloods all through Central America,” more than people — more than here in the United States. And we were uniting with all of them, all those Natives across this country — across this whole continent, I mean. And we were uniting. We were pulling them together with the American Indian Movement. That’s why we became a threat to the government so.

And later, later on, when I was arrested — after I got arrested, this one guy was telling me, he said, “You know, it just went down to Mexico someplace, one of them towns.” And he said they were organizing for resistance and stuff like this. He said, “I was down there, down there visiting them.” He said, “I went to this old — this guy told me he was the — he was some kind of medicine man or something. So I went down and visited him, and so I went into his place,” into his — he had kind of a hut-like home, I guess. And he said, “What do I see?” He said, “I see your poster on one of the walls.” That’s so far back. But I wasn’t. We went through all that stuff. And so, anyway —

AMY GOODMAN: But especially for young people to understand, I mean, you’re talking about this critical moment of 1973, ’4 and ’5.

LEONARD PELTIER: ’60s, actually.

AMY GOODMAN: What’s that?

LEONARD PELTIER: Started in the ’60s, really.

AMY GOODMAN: And also the height of the antiwar movement. And the role and the effect of the antiwar movement on the Native American movement, and vice versa? If you can talk about those critical moments?

LEONARD PELTIER: We were — I was, and others were, a lot of us Natives were — we were also involved in the peace marches and with the Blacks and the antiwar movements and things like that. We were involved in all that stuff, too. But we were working on trying to get their support, and they were working on trying to get our support. Then the hippies came out, and the hippies really helped us. The hippies did a lot to help us. They started dressing like Natives. They started doing things like Native people. And a lot of them came from very, very wealthy families. A lot of people hated them. That’s one of the reasons the government hated them, is because they were really pushing the Native issues, the culture and stuff like that.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the Trail of Broken Treaties, that was 1972. Explain what it was, which was a takeoff on the Trail of —

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, we knew that we had to get to — get the government to start honoring our treaties, because they never honored our treaties. And the only way we could do this is to go right straight to Washington. And so, we organized a group. We called it the Trail of Broken Treaties. And we all organized from all over the country. They sent representatives in old cars. We had all — nobody had new cars them days. And we all went to Washington.

AMY GOODMAN: You went?

LEONARD PELTIER: Of course, I did. Of course, I was there, too, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: This is, of course, a takeoff on the Trail of Tears. And most people, in our schools, and maybe less so especially now, will ever even know what the Trail of Tears was.

LEONARD PELTIER: Right, right, right, precisely. That was all past — everything we did, we called it — well, like the Trail of Broken Treaties, that was done out of the Trail of Tears, and the Long Walk, all them other events like that that happened. It wasn’t just the Trail of Tears. That’s what people have to understand. It was — the Trail of Tears was just one of them that became so well known, because I think 10,000 people died on that, and just laying alongside the trails and stuff from dying from sickness, malnutrition, all that stuff, on the Trail of Tears. And that’s why it got so —

AMY GOODMAN: This was President Andrew Jackson?

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The president who President Trump reveres.

LEONARD PELTIER: It was [bleep] order, yeah. He was a anti — he was a hater. And so, we were — we [inaudible], we organized. We organized under basically the same policies of exposing what was done in the past, what continued to be done.

And we still find it’s still happening today, Amy. Ann Coulter had made a public statement that — about Native people, that we didn’t kill enough of them Indians. That’s a very dangerous thing to say about anybody, because there’s a bunch of nuts out there, like, you know, you take one of them haters and everything, he can end up killing a lot of innocent Natives for — just because those type of words.

You got a president trying to do away with our treaties. If our treaties go, we go. This is the only thing to prove that we are a sovereign nation and a race of people. And if that goes, we go, as a race of people. So, it’s not — I mean, it’s not ending for us. We’re still in danger. Yeah, you see it happening in the streets, you know, I mean, right today. Look at what they’re doing in Palestine, killing women, children, babies, unborn babies. That’s what they did to us, man. And here it is still happening.

AMY GOODMAN: So, 52 years ago, 1973, the start of the American Indian Movement’s 71-day occupation of the village of Wounded Knee on Pine Ridge Reservation, occupation helping draw international attention to the plight of Native Americans, the U.S. government responding to the occupation with a full military siege that included armored personnel carriers, F-4 Phantom jets, U.S. Marshals, FBI, state and local enforcement. During the occupation, two Sioux men shot dead by federal agents, and a Black civil rights activist, Ray Robinson, went missing. The FBI confirmed in 2014, decades later, that Ray Robinson had been killed during the standoff. Most people don’t know about this history.

LEONARD PELTIER: No.

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe they’ve heard the book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. So, can you talk about Pine Ridge and Wounded Knee, especially for young people who don’t know the history?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I was in jail during the beginning of Wounded Knee, but I got out. It was about halfway through. Then I went, and I went up there, and I helped pack in stuff into Wounded Knee. And I stayed out there on the outside forces.

After we made all those trips to Washington and all that stuff, all those other demonstrations, and all those promises, they were going to do this and do that. They were going to investigate everything, all of our acquisitions and all that stuff. And we soon found out — we knew anyway, but we soon found out that was all a lie. They weren’t going to investigate [bleep]. And they didn’t.

And so, finally, the elders and the chiefs made the decision to go to Wounded Knee. AIM had no part in that decision. We cannot go anyplace in Indian Country and make policies. We can’t. That’s not — that is not us. We can’t do that. And we can’t go unless we’re invited by those people. And they just got fed up with so many more false promises and what was happening.

They were being terrorized by a group organized by — a mercenary group, I might add. They were provided with intelligence, armored person ammunition, sophisticated weapons, surveillance and stuff like this, automobiles and stuff. And the leader made that — admitted that on a national interview. So we know that’s all true. They tried to deny it at first, but they called themselves the Guardians of the Oglala Nation. And —

AMY GOODMAN: The GOONs.

LEONARD PELTIER: The GOONs, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Dick Wilson’s.

LEONARD PELTIER: Dick Wilson, all them. Nixon ordered the 82nd Airborne to go and investigate what’s going on down there. And if there was — if we were like the government was claiming, that we were communists and Marxists, and we were being financed by the communists, they were to go up there and wipe us out.

When Nixon got the 82nd Airborne involved in it, we filed a lawsuit. And it took us 10 years, but we got all this information out of the files that they had to turn over to us, right? And we found that they had went to the armory and checked out 250,000 rounds of various caliber ammunition, different sophisticated weaponry, armored personnel carriers, and finances and surveillance and stuff like that. See, that was all illegal. And that’s how we found out a lot of stuff about what they were doing there. And it was all illegal. If it would have been left to Nixon, he would have — he was going to wipe us out. But he didn’t, because, we heard, his wife stepped forward and said, “No, don’t you do that.”

AMY GOODMAN: Now, still going back 50 years, what landed you in jail? I want to go to the words in Democracy Now! in 2003. The occupation of Wounded Knee is considered the beginning of what Oglala people refer to as the Reign of Terror, from ’73 to ’76, over 60 residents killed in this period. Murders went uninvestigated by the FBI, which had jurisdiction. The period culminating in the June 26th shootout for which Leonard Peltier was imprisoned.

LEONARD PELTIER: First of all, I don’t know who the shooter is, or shooters. And I don’t — I wouldn’t tell you if I did know, so I’m not going to tell you anything in that area. But I’ll tell you — I’ll speak on the other issues, because it’s public knowledge, and it’s been — it’s been our attempts to continue to expose that stuff.

But there was a lot of Native people, traditionalists, whose homes were burned, whose houses were — was drive-by shootings. People were pulled over and beaten, and some shot, some killed. And those things are literally recordings on this. We got records of all this stuff now, so people can’t deny this stuff. The only ones that are denying this [bleep] is the United States government and the FBI and people like that.

But we faced a time called the Reign of Terror, when they were getting away with all this [bleep]. None of them were getting investigated. A lot of the older people that seen these people identified them, but the FBI still wouldn’t investigate. They were able to kill people at random. They were — and getting away with it, because they didn’t have — they had no fear of being prosecuted. The only fear they had was of us, the American Indian Movement, because we wouldn’t take their [bleep]. Every chance we got together, we got a confrontation with them. And that’s the only fear they had of anything, of any retaliations, any arrests or anything else.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re spending the hour with Indigenous elder Leonard Peltier, released to home confinement after nearly 50 years in prison. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with our global broadcast exclusive. We’re continuing our conversation with Indigenous leader Leonard Peltier, released to home confinement in February after nearly half a century behind bars. I asked him about his claims that his extradition from Canada and trial were marked by prosecutorial misconduct.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the coerced testimony of Myrtle Poor Bear, who she is.

LEONARD PELTIER: Who is she?

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, I know you didn’t know her at the time.

LEONARD PELTIER: I never knew her. Her father came to my — was going to come testify at my trial that she had a serious mental problem. And her sister was going to testify that on the day of the shootout, they were sitting there drinking beer. And we got this all on tape. And they were sitting there drinking, drinking beer, and they ran out of beer. And they were watching TV, she said, and they decided to make a run off the reservation, because it was a dry reservation. No alcohol was allowed there. And so, she says, to go buy some more beer, come back and watch some more TV. And they started driving down the road, and all of a sudden a bulletin came over the radio: a big shootout in Oglala between the Marshals, FBI, BIA cops, GOON squads against the American Indian Movement. So they were over 50 miles away. Finally, Myrtle admitted that she didn’t know me.

AMY GOODMAN: But she — her testimony said that —

LEONARD PELTIER: Her testimony in the grand jury is what got us all indicted.

AMY GOODMAN: Said she was your girlfriend and she had seen —

LEONARD PELTIER: She witnessed — oh god.

AMY GOODMAN: Seen all of this.

LEONARD PELTIER: When the lawyers came to me in Canada, they said, “Leonard” — they said, “Leonard, we got bad news for you.” And I said, “Yeah? What kind of bad news?” And they said, “Your girlfriend’s testifying against you.” And I looked at him, and I said, “My girlfriend? What do you mean? My girlfriend?” Said, “Your girlfriend.” And I said, “I don’t have a girlfriend. I got a wife, two kids.”

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about James Reynolds, the former U.S. attorney in charge of the prosecution, that helped convict you. He later becomes an advocate for your release, stating the prosecution could not prove that you had committed any offense and the conviction was unjust. He wrote to president after president — he himself was appointed by Carter — right through to Biden.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yes. Well, about 10 years ago, James Reynolds started to have a change of heart, I guess. James Reynolds said that there is no evidence Leonard Peltier committed any crimes on that reservation. And that’s pretty — he was in charge of everything.

AMY GOODMAN: What this ultimately leads to is your imprisonment for 49 years.

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The majority of your life behind bars, what this institutionalization meant for you, what it meant to be both a prisoner and considered a political prisoner around the world and a symbol of the fight for Native American rights and what happens to you when you engage in it, all of those things?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, OK, I think — I’ve been asked this question quite a bit, and it’s hard for me to answer. But I think that what really kept me strong was my anger. I was extremely angry about what they did to me and my people. And I’m still — still very, very [bleep] angry. And there was no way in hell I was going to get justice. I could have had — I had at least 14 constitutional issues that I should have been released on, at least that many, and I knew I wasn’t going to get it. I knew what it was — the courts were not going to give it to me. And, I mean, even the Supreme Court would refuse to hear my case and stuff like that. But I knew why. You know, I found evidence of them meeting with Judge Heaney. And Judge Heaney became a strong advocate for my release. But we found evidence he worked with the FBI.

And I just — I felt so much hate and anger, and what they — what they did to Native people in this country, this continent, and that kept me strong. It kept me from — oh, kept me from — I’ve been offered numerous times, or a few times anyway, that if I accepted responsibility and made statements, that everything we’ve said negative about the United States government, what their past history was, and their dealings with our — with us, as people in the nation, they would turn me loose. And I refused to do that. I refused to bow down to them. And I still refuse to bow down to them. I’m going to die with my beliefs. And I just refuse to — to me, it’s treason against my nation, my people.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re a major symbol of Indigenous power, not only in the United States, but around the world. What does that mean to you?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I hope I can use it to benefit my people. I mean, as I said earlier, we’re still in danger. It’s not over for us. We don’t get to live like the rest of the people in this country, without fear of what would happen to us if we had our treaties taken away from us. We don’t get to live like that. We still have to live under that, that fear of losing our identity, losing our culture, our religion and stuff. Most Americans don’t have to worry about that. We do. And so, the fight for, the struggle still goes on for me. I’m not going to give up. I’m not going to — I have not surrendered. I don’t want to go back to prison, although I heard that Trump was going to try to take away all of Biden’s pardons and everything else like that.

AMY GOODMAN: What would you say to young Indigenous people? I’m looking behind you at a photograph of — is it a picture of your great-granddaughter?

LEONARD PELTIER: Yeah, this one, right here.

AMY GOODMAN: And she’s wearing a T-shirt that says “strong.” How old is she?

LEONARD PELTIER: She’s now 11. Now 11. We adopted her when she was a little baby, been taking care of her ever since. And she loves me and thinks I’m the greatest thing in the world. I love her because she is the greatest thing in the world. And she was — she’s now a champion fly swimmer. She was going to — her plan was, if she wins the Olympics, she was going to take those Olympics and say, “This is for my grandpa, Leonard Peltier, who they illegally put in prison. This is for him.” I said, “Where did you come up with that?” She won’t say, but she just looks at me, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, we’ve been covering the climate movement for so many years, were here in North Dakota covering the standoff at Standing Rock, the Sioux-led, Indigenous-led global movement to preserve the environment. And this year, the U.N. climate summit is in just the tip of the rainforest, Belém in Brazil. And each of these U.N. climate summits, we see Indigenous people, especially young Indigenous people, there fighting for the planet. Do you see the voice of Indigenous people on the climate movement as hopeful?

LEONARD PELTIER: We’ve been talking about this for 250 years — or, no, since America was first organized. We still — when we pray and when we — whatever we do, we still talk about Mother Earth and other environment stuff. We haven’t stopped. We never will stop. You know, we are still strong on environmentalists.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Leonard Peltier, I want to say thank you so much for inviting us into your home. I’m so glad we’re not coming to a prison.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, so am I.

AMY GOODMAN: Indigenous leader Leonard Peltier at his home on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota on his 81st birthday weekend. Special thanks to Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Denis Moynihan, Mike Burke and, to you observant ones, to my pup Zazu, the newshound. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options