Topics

Guests

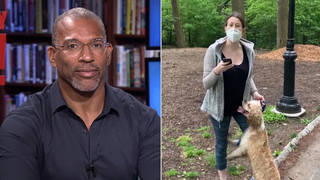

- Damu Smithnational associate director of Greenpeace.

- Peter Montagueof Rachel’s Environment & Health Weekly.

Over 500 environmental activists recently gathered in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, for the Third Citizens’ Conference on Dioxin. Damu Smith, national associate director of Greenpeace, talked about environmental racism and classism, and the tendency for polluting petrochemical companies to locate their factories in poor, predominantly African American communities of the South. He also said that there needed to be more respect for people of color as leaders in the environmental movement. Another speaker, Peter Montague of Rachel’s Environment & Health Weekly, encouraged listeners to read the new book entitled Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Our Intelligence, and Our Survival? However, Montague felt that the book did not go far enough in laying blame on corporate polluters, who exist solely to turn a profit and are not guided by any moral code. Montague said that it is time for the public to take control and introduce the concepts of morality and liability into the corporate world.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: You’re listening to Democracy Now!, Pacifica Radio’s daily national grassroots election show. Tuesday is the California primary. Monday, on this show, we’ll be speaking to California environmentalists, from Silicon Valley to the low-income African American community of Richmond to the breast cancer capital of San Francisco. But for the moment, we return to the South, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where over 500 environmental justice activists spent last weekend strategizing over how to take on some of the country’s most powerful corporations to stop the production of dioxin, an unwanted byproduct of incineration and many industrial processes, so many of which are located in low-income communities of color. Damu Smith is national associate director of Greenpeace in Atlanta.

DAMU SMITH: Good morning, sisters and brothers.

AUDIENCE: Good morning.

DAMU SMITH: Welcome to the South. How many people here are from the South? Raise your hand. The South is in the house. This is the poorest region of the country. This is the bastion of racism in America, home of the civil rights movement, place where Native people resisted conquest and relocation, a place where farmworkers from Texas to Louisiana to Florida labor in the fields with dioxin-laden pesticides. This is the region where workers work under the most inhumane, unregulated, unorganized conditions. You are in the state of Louisiana, where the white electorate in this state almost elected a member of the Ku Klux Klan to governorship of this state. You are in the middle of Cancer Alley, where we have the highest rates of cancer in the nation, and perhaps in the world, where 134 petrochemical companies line the Mississippi River, where these petrochemical companies have literally destroyed historically African communities founded by former slaves, where Black people have had to be relocated to other parts, outside of the context of their traditional places, because of racism. You are in the home where slavery once flourished. You are in the home where sharecropping once flourished. You are in the place in this nation where racist, violent and white vigilante terror once ran rampant throughout this region, and the legacy of that persists today in the South and all over the United States. You are in this part of the country where the environmental justice movement has a glorious history, where in 1982 the people of Warren County, North Carolina, in an African American community rose up trying to stop the PCBs being dumped in their community. And Dollie Burwell is back there. Give her a hand. She helped to lead that movement. You are in the South, where we have Sumter County, where we have the world’s largest landfill, once again in a predominantly African American county.

But I hear Malcolm X’s voice talking to me now. He says, “Stop talking about the South. Anytime you’re south of the Canadian border, you’re south.” So, racism all over the country, this is where we are. Racism, the concept of white supremacy and nonwhite inferiority, is the ideology that has governed this nation from the beginning. Within the context of environmental racism, it means that we have an unequal distribution of wealth, rights and privileges between whites and nonwhite people. It means that, therefore, we have an unequal distribution of the poison, resulting in people of color sharing a disproportionate burden of the risk and the effects and the consequences and the suffering and the sickness and the death. It also means, within the context of injustice, that poor white people, too, suffer because of classism in this country. But when you add the class and the racial dimension to what is happening to people of color, we are assigned even a more severe status. Who has the dirtiest jobs? Answer me. People of color. Who live closest to the incinerators?

AUDIENCE: People of color.

DAMU SMITH: Who lives closest to the landfills?

AUDIENCE: People of color.

DAMU SMITH: Where are they trying to put most of the nuclear waste?

AUDIENCE: People of color.

DAMU SMITH: That’s what’s happening. The environment is where we live, work and play, and in all of these areas, people of color are disproportionately impacted. The studies have shown it. A movement has grown, an environmental justice movement that confronts environmental racism frontally. It is an inclusive movement. The people of color-led environmental justice movement is multiracial, multicultural, multiethnic, multilinguistic. We have made it a cornerstone of what we are trying to do. We’re not going to have a meeting, even if it’s people of color-led. It’s always going to be based on that principle. White people in the environmental movement must learn a lesson from that movement, so that we don’t have people of color leadership and people of color organizers disrespected as part of the organizing process and as part of the leadership.

What it means, we have Principles of Environmental Justice. And by the way, in case anybody is mistaken, the Principles of Environmental Justice were adopted in October of 1991 at the People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. And the principles that you see in the booklet were reprinted from the proceedings published by the Commission for Racial Justice of the United Church of Christ from that meeting, just so we’re clear on the origin of that document.

And I want to conclude by saying that we must lift up the statistics around dioxin that speak to this fact. The data suggests that African Americans have 33% more dioxin in their bodies than whites. Of the 177 chlorinated synthetic chemicals found in our bodies, in terms of the statistics around that, women have 15% more. African American women have 30% more. If you are people of color and you’re involved in subsistence fishing and hunting, you have the possibility, because of the fact that the animals have digested dioxin, of getting more dioxin in your bodies. The poison is not being distributed equally. Nobody should be poisoned. So, what this means is this: When we are organizing this movement, we cannot be blind, deaf and dumb on the question of racism and environmental racism and environmental injustice. We have to raise this as part of our strategy in everything we do. This must be at the center of our thinking alongside everything else that we’re doing. Thank you very much, brothers and sisters.

AMY GOODMAN: Damu Smith is national associate director of Greenpeace in Atlanta. He was also one of the organizers of last year’s first People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. In the background, you hear Margie Williams of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice in New Orleans.

In the last week, a new book was released called Our Stolen Future. One of its authors, Dr. Theo Colborn of the World Wildlife Fund, joined us on Democracy Now! last Friday. While many environmentalists at the dioxin conference applauded its focus on dioxin and endocrine disruptors, participants like Peter Montague, editor of Rachel’s Environment & Health Weekly, the leading fact sheet of the dioxin movement, felt it didn’t go far enough.

PETER MONTAGUE: Our conference began with a speaker named Pete Myers, who’s the co-author of this book. I urge you to get this book and read this book. If you don’t know the facts behind this story, you need to know the facts behind this story. The book is called Our Stolen Future. Our Stolen Future. And on the cover, it asks, Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Our Intelligence, and Our Survival? — A Scientific Detective Story. One thing that’s not in this book is the answer to the question: Who stole our future? Who stole our future? And, of course, the answer is corporations stole our future.

Let me get organized here so I can make a coherent presentation about the nature of this creature, the corporation. It is a legal entity. It was created by us. It was created by our parents and our grandparents, thinking they were doing a good thing. The corporation is formed by a state legislature, which issues a piece of paper called a corporate charter. And if a group of people get a corporate charter, they are then incorporated. And this corporation then takes on a life of its own. It is formed for one purpose: to make a profit for investors. It is formed for only one purpose: to make a profit for investors. If it does something else, it can be sued by those investors for breach of fiduciary trust, for failure to focus on making a profit. And so, the people who are inside corporations are not free to act upon their consciences. They are not free to do what is right and what is good, and what they, as human beings, know is right and good. They must do whatever will make a profit. And so, when they get into the corporate organization, they lose their humanity. They lose their conscience. They lose their sense of right and wrong. They lose their capacity to be guided by their sense of right and wrong. They lose their humanity. And in some sense, we need to liberate them from those organizations.

Another characteristic of this legal entity, the corporation, is that there is limited liability. You all know from your own experience growing up that liability, pain, is a very important — you get very important lessons from life by the pain that you cause to yourself by making mistakes. If you can’t feel pain, you can’t be guided toward a proper way to behave. You become some kind of a sociopathic criminal person if you can’t feel pain. If you were free to just be aggressive and punch people whenever you wanted your way, if they didn’t punch you back, and you say, “Oh, I better not do that. That hurt,” you’d go nuts. You’d be a crazy person. So, being able to get feedback in the form of pain — or, the legal term, “liability” — is very, very important. If you can’t feel liability, you can’t learn how to behave in a civilized fashion. And that’s the nature of corporations. They are not able to behave in a civilized fashion. That’s because they have limited liability. We need to take that away. We have the power. We are the ones who created these entities. We have power over them. That’s the nature of our democracy. We just need to focus on taking that power back and asserting that power.

Another characteristic of corporations is that they must grow. They need more market share. They need to be more powerful in their community. That helps them become stable. That helps them survive. And so they’re constantly trying to grow. In order to grow, they must externalize their costs. They must dump their costs onto their community. If they’re faced with a choice of dumping a hundred pounds of crud into the environment free or paying $500 to process that a hundred pounds of crud, which do you think they’re going to choose? They’re going to dump it into the environment. That’s called externalizing your costs, because every dollar they save is a dollar that they’ve earned without doing anything. So they dump their costs onto us. A worker gets sick, they’re facing a choice: They can either nurture that worker, help that worker get well, provide benefits and healthcare for that worker, or they can fire that worker and tell the worker to go to the emergency room and let the public hospital pick up the tab. Which are they going to do? Of course, they’re going to fire that worker and let the public pick up the cost of that worker’s illness. They are not going to expend their money on it. That’s externalizing their costs. It’s in the nature of corporations that they do this.

They are also protected by the Bill of Rights. They were not given this by the Constitution of the United States. They were given this by a judge in 1886. This was a — this was a judicial decision by a judge who was not even elected to that office, by an appointed official. And since then, we have failed to take that back from them, to take that away from them. So, when they put money into a legislative campaign, that is protected as free speech. Bogus, completely bogus. The rule of thumb should be, if it doesn’t breathe, it isn’t protected by the Bill of Rights.

We have the power to take these things back, and the time is right to begin. Businessweek has a — on I think it’s March 11th, Businessweek has a really remarkable poll by the Harris polling organization, a mainstream surveying organization. They asked the American people two questions. One, U.S. corporations should have only one purpose, to make the most profit for their shareholders, and their pursuit of that goal will be the best for America in the long term. How many — what percent of the American people believe that? Five percent. Five percent think that corporations should have — the alternative was U.S. corporations should have more than one purpose. They also owe something to their workers and their communities in which they operate, and they should sometimes sacrifice some profit for the sake of making things better for their workers and communities. Ninety-five percent of the American people went for that.

So, the time is right for a political movement like ours to not only focus on protecting our future and our health — and I don’t want to take — I don’t want to divert us from that basic goal of protecting our future and our health. That is why we are in this room. We are together to protect our future, our children, our health, our communities. We must not divert ourselves from that. But we’ve got to recognize that if we’re really going to get past fighting brush fires, we need to control this corporate entity that we created and which is now out of control. If we are — if we are going to take control of our local economies — and that’s what Elaine Gross of Sustainable America is about, and I urge you to pay attention to Sustainable America — that’s the other side of protecting your environment, is to protect your local economy and take control of your local economy. And both of those things — protecting the environment and protecting your local economy and taking control — means taking control away from corporations.

Think of the good fight that you’ll get into if you try to — if you start a campaign as part of your local struggle to control the economy and protect your environment and your family, start a campaign that says, as a matter of law, no corporation or other entity which produces or emits dioxin will be permitted to do business in your community. Take it to the — take it — take it to the next step. Let’s demand control directly by the people over corporate behavior. They should not be allowed to do business in your community if they are dumping this super toxic poison that is stealing our future. They must not be permitted to do this. We have the power. It’s time we asserted that power. And that will be just the first step. Let’s get into a good fight over democracy versus corporate power.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Montague, editor of Rachel’s Environment & Health Weekly, based in Annapolis, Maryland. His email address, erf@rachel.clark.net. That’s erf@rachel.clark.net. If you’d like to get a copy of today’s “Living Democracy” special, you can call the Pacifica Archives at 1-800-735-0230. That’s 1-800-735-0230. Vietnam veterans and dioxin, up next after this break.

Media Options