Topics

On June 26, 1975 two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ron Williams, entered the Jumping Bull Ranch in South Dakota. The FBI says they were seeking to arrest a young Native American man they believed they had seen riding in a red pick up truck. A large number of supporters of the American Indian Movement, known as AIM, were camping on the property at the time. According to witnesses there, the more than thirty men, women and children on the property were surrounded by more than 150 FBI agents, SWAT team members, BIA police and local posse members, and barely escaped through a hail of bullets. The FBI disputes that account. [includes rush transcript]

When the gunfight ended, a Native American named Joe Stuntz, as well as the two FBI agents Coler and Williams, lay dead. The agents had been wounded in the gunfight and then shot point blank through the head.

Three people were charged with first degree murder for the deaths of the agents. They were all AIM leaders–Leonard Peltier, Dino Butler and Bob Robideau. Butler and Robideau stood trial separately from Peltier, who had fled to Canada, saying he didn’t believe he would receive a fair trial in the United States. The two men were found not guilty by reason of self-defense.

Shortly after, Leonard Peltier was extradited from Canada and was tried for the murders. He declared that he was innocent. But he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He has spent the last 25 years in a federal penitentiary, always professing his innocence.

Today, Leonard Peltier is asking President Clinton to grant him executive clemency before he leaves office. Time is running out, with just weeks to go before the presidency changes hands.

In an exclusive interview with Pacifica’s WBAI last month, Democracy Now! asked President Clinton whether he would grant this clemency request. Clinton addressed the Peltier case publicly for the first time, saying that he would make a decision on the case before he left the White House.

The FBI’s director Louis Freeh countered with a letter to Clinton asking him not to free Leonard Peltier. Attorney general Janet Reno chastised Freeh for going public on the case, saying that “these matters should be confined to a discussion with the president.” FBI agents are also planning to hold a rally this Friday in front of the White House opposing clemency for Peltier. Thousands also protested in front of the United Nations this past Sunday calling for Clinton to grant Peltier clemency.

Today, part two of a debate between the FBI and Peltier’s attorneys.

Tape:

- Leonard Peltier, Native American activist imprisoned for almost 25 years. Speaking from Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas.

- President Clinton, speaking with Democracy Now! on Election Day.

Guests:

- James Burrus, Assistant Special Agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis division.

- John Sennett, President of the FBI Agents Association.

- Jennifer Harbury, attorney for Leonard Peltier.

- Bruce Ellison, Attorney for Leonard Peltier.

Related links:

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, we bring you part two of a debate on the case of Leonard Peltier, who’s right now at the Leavenworth prison in Kansas.

On June 26, 1975, two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ron Williams, entered the Jumping Bull Ranch in the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota. The FBI says they were seeking to arrest a young Native American man they believed they had seen riding in a red pickup truck. A large number of supporters of the American Indian Movement, known as AIM, were camping on the property at the time. According to witnesses there, the more-than-thirty men, women and children on the property were surrounded by more than 150 FBI agents, SWAT team members, BIA police — that’s Bureau of Indian Affairs — and local posse members, and barely escaped a hail of bullets. The FBI disputes this account.

When the gunfight ended, a Native American named Joe Stuntz, as well as the two FBI agents, Coler and Williams, lay dead. The agents had been wounded in the gunfight, then shot point-blank through the head.

Well, three people were charged with the murder of the agents. They were all AIM members: Leonard Peltier, Dino Butler, Bob Robideau. Butler and Robideau stood trial separately from Leonard Peltier, who had fled to Canada, saying he didn’t believe he could get a fair trial in the United States. The two men were found not guilty — that was Robideau and Butler — by reason of self-defense.

Shortly afterwards, Leonard Peltier was extradited from Canada and was tried for the murders. He declared that he was innocent, but he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He has spent almost twenty-five years in a federal penitentiary, always professing his innocence.

Today, Leonard Peltier is asking President Clinton to grant him executive clemency before he leaves office. He has been asking for executive clemency for the last seven years. Time is running out, with just weeks to go before the presidency changes hands.

A few months ago, I had a chance to speak with Leonard Peltier at the Leavenworth prison about his case. And today, we’re going to play an excerpt of this, and then we will turn to the debate.

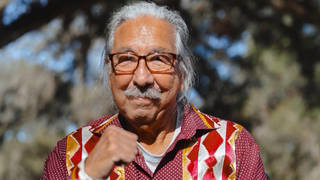

LEONARD PELTIER: My name is Leonard Peltier. I’m a Lakota and Chippewa Native American from the state of North Dakota. I am currently serving two life sentences for the deaths of two FBI agents in Leavenworth United States Penitentiary.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you kill the FBI agents?

LEONARD PELTIER: No, I did not. No.

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe we could go back to that day that these FBI agents were killed, and you could tell us what happened.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, at that time, there was a — what is known as today as a region of terror going on against traditional people from the so-called progressives under a tribal chairman named Dick Wilson, who was very corrupt, who organized his own private police force, kind of like a Contra group, and started terrorizing his own people, the own traditionalists on the reservation. So the traditionalists asked for the help of the American Indian Movement. And the end result, after long protests and my getting no responses from any law enforcement agency in the country, Wounded Knee II was then occupied, and there was a seventy-one-day siege.

After that, he, Dick Wilson, again intensified his GOON squads. And the General Accounting Service, an agency of the United States government, did an investigation, and before the funding was — ran out, they found over sixty murdered Indian people, traditionalists. And so on June 26th, we didn’t know it at the time, but we knew later from Freedom of Information documents, that the FBI with the GOON squads were planning on attacks on the Jumping Bull Ranch and another ranch in Kyle — that’s another community on the reservation — that they were declaring American Indian Movement strongholds. And on June 26th, a firefight started. And the end result was two FBI agents and one Indian — young Indian man was killed.

And they indicted four of us — Bob Robideau, Dino Butler, Jimmy Eagle. After a year, they dropped the charges on Jimmy Eagle. And Bob and Dino went to trial in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and was found not guilty by reasons of self-defense. I was later — my trial was mysteriously moved from Cedar Rapids, which I was supposed to go to trial at the same place under the same judge as my co-defendants — was mysteriously moved to Fargo, North Dakota.

Later documents show that the FBI then went judge shopping to get a judge to work closely with them. And Judge Paul Benson agreed to do it. And I was not allowed to put up a defense. They manufactured evidence. The murder weapon was perjured by government witnesses. And the judge erred in his rulings, which prevented me from putting up a defense.

This was on my — this all came out in my 1985 appeal under the ballistics. They had taken this gun during the trial and claimed — no one testified this was my weapon, by the way. But they had taken this weapon and said this was the murder weapon and this belonged to Leonard Peltier. Well, we weren’t allowed to properly cross-examine the firearms expert of the FBI. So this was left then as only on the word of the prosecutor that this was my weapon and that this was the murder weapon.

Through the Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, we were able to discover that they had done a firearm test on this weapon and it came out negative. So I filed a 1985 appeal. And because my attorney, Bill Kunstler, made a mistake, I am now serving two consecutive life terms in prison, for — possibly for the rest of my life, if it’s left up to the FBI, on the technicality.

AMY GOODMAN: What was the mistake?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, the judge asked him if I was changing my plea and also because Norman Brown testified that he’d seen me down by the agents, the car — the agents’ car, and Kunstler agreed with him that Norman Brown testified to this, and this was never — and this was untrue. Norman Brown never testified to that. In fact, nobody testified to that.

AMY GOODMAN: Who was Norman Brown?

LEONARD PELTIER: He was one of the three young men that was taken and interrogated under very brutal tactics — tied to chairs, their lives were threatened, their families were threatened — to testify against Bob and Dino and myself.

AMY GOODMAN: Leonard Peltier, why weren’t you tried along with your co-defendants Dino Butler and Bob Robideau?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I was — at the time, I had got arrested in Canada. I was — I’d been back and forth to Canada numerous times, about four times before I was arrested over there. But going through Canada with a lot of Native Americans that lived in Montana and Washington state, North Dakota, Minnesota, it’s like crossing another border for us. All across the Canadian border, there’s a treaty with the United States government and Canada that we’re — Native Americans are allowed to do this, because they split some of our lands, our reservation lands, and part of it was Canada and part of it the United States. So we go across like going to another state.

And I had been over there three or four times. But I finally got arrested over there, so I decided to fight extradition, because I was, you know, well aware that Native Americans could not receive justice in the courts and that, you know, 99% of us would get railroaded, so — especially the American Indian Movement people. We — so I started to fight extradition. But I also made a formal request that I wanted to go to trial with my co-defendants. But somehow the government got to speed up the trial, and they took my co-defendants to trial first.

AMY GOODMAN: Leonard Peltier speaking a few months ago to us from Leavenworth prison. On Election Day, I got a chance to ask President Clinton about Leonard Peltier’s case.

AMY GOODMAN: President Clinton, since it’s rare to get you on the phone, let me ask you another question. And that is, what is your position on granting Leonard Peltier, the Native American activist, executive clemency?

PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON: Well, I don’t have a position I can announce yet. I think if — I believe there is a new application for him in there. And when I have time, after the election’s over, I’m going to review all of the remaining executive clemency applications and, you know, see what the merits dictate. I will try to do what I think the right thing to do is based on the evidence.

And I’ve never had the time actually to sit down myself and review that case. I know it’s very important to a lot of people, maybe on both sides of the issue. And I think I owe it to them to give it an honest looksee. So part of my responsibilities in the last ten weeks of office after the election will be to review the requests for pardons and executive clemencies and give them a fair hearing. And I pledge to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: And you will give an answer in his case?

PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON: Oh, yeah. I’ll decide, one way or the other.

AMY GOODMAN: President Clinton, speaking on Election Day. You are listening to Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! When we come back, Jennifer Harbury, Leonard Peltier’s attorney, and agents of the FBI who are fighting to keep him in prison. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As President Clinton weighs executive clemency for Leonard Peltier, there’s going to be a rally of FBI agents outside the White House on Friday. There was a large rally of thousands in New York across the street from the United Nations on International Human Rights Day this past Sunday of people calling for executive clemency for Leonard Peltier.

We’re joined on the phone now by James Burrus, Assistant Special Agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis division, which did the investigation of the murders of the FBI agents. What is the main thrust of your argument, just to recap from yesterday, for why you feel Leonard Peltier should not get executive clemency after twenty-four years?

JAMES BURRUS: Well, first of all, he doesn’t, and most important, he doesn’t deserve it, Amy. He — you’ve got a lot of listeners out there who have just spent ten minutes listening to Leonard Peltier’s version of the facts. And obviously I think Leonard neglects to put a lot of the facts into play. He’s just plain wrong on the types of — the way that he characterizes the evidence. He’s just plain wrong on a lot of the things that he says.

Twenty-five years ago, Leonard Peltier was camping on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. He’s not a Native American activist that was brought there because he brings good and peaceful ideas, that he’s a calmer, that he’s a peacemaker. Leonard was brought to the reservations by more militant parts of the American Indian Movement for his muscle. He has a long history of violence, of using muscle, shooting at police officers. He was wanted at the time by the FBI for the attempted murder of a Milwaukee police officer at the time that he was out on the reservation. He was not brought there because he was a famous Indian activist. He was brought there because of his muscle.

Now, these two agents were looking for a suspect that they had a valid arrest warrant for, and they just happened to run into Leonard Peltier. A shootout erupted as a result of that — as a result of the agents looking for a guy that was riding in a vehicle that happened to look like Leonard Peltier’s. A shootout erupted. The agents fired about five shots at the — at people that were 200 yards away. If you know anything about weapons, you know that a service revolver’s effective range is about fifty yards. Leonard and his crew were shooting at our agents with rifles that reached 200 and 300 yards.

Our agents — more than 125 bullets hit the vehicles of the agents. The two agents that were by themselves, they were very young, a lot like the radio-listening audience that you have. They were twenty-six, twenty-seven years old, fresh into the FBI. They were quickly wounded, two or three shots. One guy was unconscious. The other guy was over trying to put a tourniquet on Jack Coler, when these three guys walked up. And there’s plenty of evidence and plenty of witness testimony that puts Leonard Peltier down by the agents’ cars.

Now, what happens next is that Leonard Peltier’s weapon is used to execute both of these agents at pointblank range. This isn’t —

AMY GOODMAN: And how do you know it was his weapon?

JAMES BURRUS: Well, we know it’s his weapon based on the fact that a shell casing from his weapon ejected into the trunk, into the wheel well of Jack Coler’s car. Ballistics tests determined that the extractor rod from Leonard Peltier’s weapon was the extractor rod that pulled that bullet out of the gun and into Jack Coler’s wheel well.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, we had this discussion yesterday, but, Jennifer Harbury, you contested the description that Burrus has of the ballistics test.

JENNIFER HARBURY: That’s correct, Amy. There are two tests that can be done, two ballistics tests. The far more precise test is the firing pin test. That firing pin mark is made when a bullet is fired from a rifle. The other test, which is far less accurate, is the extractor test. The extractor marks can be made when the bullet is fired or when it is simply extracted, you know, just popped out of a casing.

The shell casing in question that Mr. Burrus is referring to was rushed to the FBI lab right after this tragic shootout occurred, which I again would point out took the life of a young Native American, who was also shot through the head and is rarely mentioned.

But at any rate, the firing pin test was performed by the FBI ballistics lab. The more precise test was performed, and it was found that that bullet casing could not possibly have come from that rifle. It says right there, “different firing pin.” Not only that, in writing, there was a decision made not to share that with the defense team.

AMY GOODMAN: James Burrus, your response to that?

JAMES BURRUS: Yes, I mean, it’s just — it’s not true. There’s two ways that you can determine it. The test was inconclusive as regard to the firing pin there. But a bullet has two markings on it when it’s fired into a weapon. Number one is the firing pin. Number two is the extractor rod.

But the Eighth Circuit has determined already, and its very wording says when all — this is — I’m quoting. “When all is said and done, that bullet came from that weapon.” I mean, it’s just — it’s not even a debatable fact anymore. That bullet came from that weapon. It’s been established not only by the jury, but by the judge and by the Eighth Circuit.

AMY GOODMAN: Jennifer Harbury, your response to that?

JAMES BURRUS: Wait a minute, let me finish. That particular bullet has markings that identify it specific to the extractor rod on Leonard’s weapon.

AMY GOODMAN: Leonard Peltier’s attorney, Jennifer Harbury.

JAMES BURRUS: Thank you.

JENNIFER HARBURY: Yes, again, let’s go back to that Eighth Circuit ruling. What that Eighth Circuit ruling says that, of course, given that the more precise test, the more accurate test, the firing pin test, was negative — not maybe negative — was specifically negative and was withheld from the defense team, that this was a very serious error. Unfortunately, the court continued, “Even though the jury, but for all of the FBI misconduct in this case, including but not limited to the firing pin test, the jury might well have ruled that Leonard Peltier was innocent.” They specifically left open the fact that Leonard Peltier might well be innocent, and the US attorney at that stage was openly admitting in court that no one knows who pulled that trigger.

Now, what the court decided then is that even despite all of this, they could —

AMY GOODMAN: We’ve just lost Jennifer for a minute, but we do have on the line with us Bruce Ellison, who is the other attorney for Leonard Peltier, the case we’re talking about today. Again, President Clinton in these weeks is weighing whether to grant executive clemency to a number of people, including Michael Milken, Susan McDougal, Webster Hubbell. Leonard Peltier is one of those that he is weighing. And as you heard him say, he is going to make a decision, one way or the other

I wanted to ask Bruce Ellison about the ethics complaints that have been brought against the FBI.

BRUCE ELLISON: Well, actually Jennifer’s the best person to answer the questions on the ethics complaint. But we have raised a number of issues that state the history of FBI misconduct in this case. And it’s important, we would suggest, to note that this misconduct, which has resulted in an unfair trial and unfair proceedings, is not just our statement. I mean, Amnesty International has been calling for an independent inquiry into the use of the criminal justice system by the FBI and other agencies for political purposes, citing the Peltier case as an example. The US Commission on Civil Rights has urged for over twenty years that there be a congressional investigation of what the FBI was doing on Pine Ridge. And we continue to support that particular [inaudible].

AMY GOODMAN: Bruce Ellison, let us go back to Jennifer Harbury to ask her about these ethics complaints, because yesterday in the first part of the discussion, we didn’t get to talk about these. Jennifer Harbury.

JENNIFER HARBURY: Yes, and, Amy, I just got cut off there in mid-sentence. What I was trying to say is that the court found that, given the recent Bagley standard, they could not give Leonard a new trial, even though they had showed, because of the ballistics test, that he might well have been ruled innocent. And again, that judge has written to firmly support clemency. And the US attorney at that stage has long since admitted that no one knows who fired those fatal shots.

About the ethics complaint, there are three bases that we really brought this complaint on. The first is on the basis of FBI close collaboration during the Reign of Terror with a very murderous and very violent GOON squad, Guardians of the Oglala Nation, a local vigilante group working closely with the Tribal Chairperson Dick Wilson and directly implicated in the sixty-four murders of AIM members and supporters and Lakota traditionalists across the reservation. There does exist film footage, for example, of the FBI agents walking up to an illegal roadblock, shaking hands and laughing with GOON members. There’s also film footage of a GOON leader laughing about a brutal attack on AIM supporters made recently and saying directly to the camera that, of course, the FBI knows I have these illegal weapons. They were at my house last night, and one of them gave me armor-piercing ammunition. The FBI simply saw the GOONs as a necessary ally in combating a fledgling civil rights movement called AIM, American Indian Movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Let John Sennett respond to that, President of the FBI Agents Association.

JOHN SENNETT: Well, thank you. As I’ve been listening to this morning’s discussion and yesterday’s and all of the previous discussions on this general subject, it — what seems so clear to me is the — is that this is the effort to characterize this investigation and prosecution of Leonard Peltier twenty-five years ago as a political process, rather than a law enforcement and judicial process.

AMY GOODMAN: But, John Sennett, could you respond to the particular point, because we don’t have much time.

JOHN SENNETT: Well, I — the particular points that Ms. Harbury is asserting are completely foreign to me. I don’t know what she’s talking about, and I don’t know where this information is substantiated.

AMY GOODMAN: Jennifer Harbury, your corroborating evidence that the GOONs, the Guards of the Oglala Nation, were working with the FBI.

JOHN SENNETT: And I don’t really know what it has to do with anything anyway. I mean, she says there’s a videotape of FBI agents laughing and shaking hands with GOON members. What does that mean? Does that mean that they were allies? Does that mean that there was an arrangement, an unholy alliance between the FBI and the GOONS? That’s quite a stretch. When we’re dealing with people, we deal with them, we use —- I have no idea what these agents -—

AMY GOODMAN: Jennifer Harbury, your point in saying that they were collaborating. Why should that change the story?

JENNIFER HARBURY: Because Mr. Peltier’s conviction with all of this falsified evidence and coerced and terrorized witnesses, as we’ve been discussing, was part and parcel of this very ugly chapter of civil rights violations in recent American history. It was part and parcel of a series of prosecutions in which judges seriously rebuked the FBI for similar actions in other prosecutions against AIM.

The other major parts of our ethics complaint, though, include failing to protect and failing to equally apply the laws on Pine Ridge in that era and also making statements such as, “Leonard is definitely the person who shot these agents pointblank through the head.” All of the courts have always supported that, when, in fact, even the US attorney admits that no one knows who fired those shots. Even the FBI’s own ballistics test shows that the bullet did not come from Mr. Peltier’s gun. And —

JOHN SENNETT: Well, Jim Burrus answered this point very explicitly and clearly yesterday and articulated the legal standard that’s necessary for Leonard Peltier to have been convicted of murder.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask James Burrus what you make of the Attorney General Janet Reno basically rebuking Louis Freeh, the head of the FBI, for coming out with a statement saying that Leonard Peltier should not be given executive clemency, this in the last week.

JAMES BURRUS: You know, I haven’t seen that. I’ve heard about it from various people. I’ve looked for it in the newspapers to get more information on that. But, I mean, I clearly haven’t seen that.

Ms. Harbury talks about the sixty-four murders as if they actually — as if those were actual murders that took place on Pine Ridge. It’s just not true. We’ve already adjudicated all of those murders, except for a few that we already know about and we continue to investigate. It’s very easy to make those type of statements. And I think in normal defense attorneys’ tactics, if they can’t win on the facts, then they try to drum up some huge conspiracy. And I think that just doesn’t serve this debate very well.

What happened to those two agents executed at pointblank range is a horror. And I think turning attention away from that and onto president — Janet Reno’s rebuke of Louis Freeh for speaking his mind on this issue really does the memory of the agents a disservice.

JOHN SENNETT: I would like to ask Mr. Ellison or Ms. Harbury what level of culpability they think Leonard Peltier has. And if he — if they believe he doesn’t have any level of culpability, why they think he doesn’t.

AMY GOODMAN: Jennifer Harbury.

JENNIFER HARBURY: Yes, I think that Mr. Peltier has the same level of culpability that his friends, Mr. Butler and Mr. Robideau, have. They were on that ranch. They were taken by surprise when the shootout began between the two different vehicles. And as in the case of Mr. Robideau and Mr. Butler, they acted in self-defense.

I think the theory that I’ve heard before that this is like a bank robbery, where several people drive to a bank and somehow a bank guard becomes — is shot and killed in the process, is off. There was no conspiracy. There was no plan here to kill anyone. The FBI agents in unmarked cars drove off onto the ranch and took everyone by surprise.

JOHN SENNETT: So you think that this was more in the nature of a firefight between freedom fighters and secret police?

JENNIFER HARBURY: I would never use the term secret police, coming as I do from the Guatemalan context, excuse me.

JOHN SENNETT: Well —

JENNIFER HARBURY: But what I do think happened is that there — that the evidence shows that happened is that there was a firefight, that three people were tragically killed. I do give great respect, let me add, to all three persons that were killed. This is a tragedy, no matter how you look at it.

But I think the greatest tragedy of all is that instead of properly investigating the case and really getting to the bottom of who did pull the trigger for the pointblank shots, that a local Native person, a Native American leader, was de facto lynched through the use of false evidence and that in twenty-five years, the US judiciary system has been unable to resolve those problems.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, on that note —

JOHN SENNETT: Well, I don’t want to concede —

AMY GOODMAN: We have twenty seconds.

JOHN SENNETT: OK. I don’t want to concede Leonard Peltier’s guilt to any degree at all. But some — one of these people standing over Agent Coler’s and Williams’s bodies finished them off.

JENNIFER HARBURY: Some person.

JOHN SENNETT: Some person.

JENNIFER HARBURY: Unidentified.

JOHN SENNETT: And was that person —

JAMES BURRUS: It’s Leonard Peltier. Let me interrupt. It is Leonard Peltier. The evidence has shown that. The three of them were tried together —

AMY GOODMAN: We have to go, I’m sorry to say, but if people want to get more information on this case, you can go to the website, noparolepeltier, put together by the —

JAMES BURRUS: The FBI has a website.

AMY GOODMAN: The — and the FBI website, and on the other side, the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee is freepeltier.org. Peltier is spelled P-E-L-T-I-E-R. I want to thank James Burrus and John Sennett of the FBI, Jennifer Harbury and Bruce Ellison, lawyers for Leonard Peltier.

Media Options