Guests

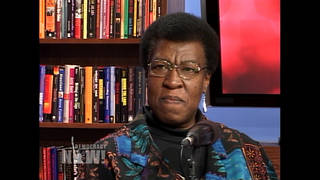

- Octavia Butleraward-winning science fiction author.

We speak with Octavia Butler, one of the few well-known African-American women science fiction writers. For the past thirty years, her work has tackled subjects not normally seen in that genre such as race, the environment and religion. [includes rush transcript]

The Washington Post has called Octavia Butler “one of the finest voices in fiction period. A master storyteller who casts an unflinching eye on racism, sexism, poverty and ignorance and lets the reader see the terror and beauty of human nature.” Octavia has described herself as an outsider, and “a pessimist, a feminist always, a Black, a quiet egoist, a former Baptist, and an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive.”

Octavia Butler wrote her first story when she was ten years old and as she has said, she has been writing ever since. Race and slavery is a recurring theme in her work. Her first novel, Kindred was published in 1979. It tells the story of a black woman who is transported back in time to the antebellum South. The woman has been summoned there to save the life of a white son of a slave owner who turns out to be the woman’s ancestor. Octavia is the author of ten other novels including the Parable of the Sower series. She is the recipient of many awards including the Nebula Award and the MacArthur “genius” award. Her latest book is called Fledgling.

- Octavia Butler, award-winning science fiction author

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, normally we don’t spend a lot of time talking about science fiction on Democracy Now! But today we’re joined by one of the preeminent voices writing in the genre today. Octavia Butler is one of the few well-known African-American women science-fiction writers. For the past 30 years, her work has tackled subjects not normally seen in that genre. The Washington Post has called her “one of the finest voices in fiction—period. … A master storyteller [who] casts an unflinching eye on racism, sexism, poverty, and ignorance and lets the reader see the terror and the beauty of human nature.” Octavia has described herself as an outsider, a, quote, “pessimist, a feminist always, a Black, a quiet egoist, a former Baptist, and an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive.”

AMY GOODMAN: Octavia Butler wrote her first story when she was 10 years old, and she has said she’s been writing ever since. Race and slavery is a recurring theme in her work. Her first novel Kindred was published in '79. It's the story of a black woman who’s transported back in time to the Antebellum South. The woman has been summoned there to save the life of a white son of a slave owner, who turns out to be the woman’s ancestor. Octavia Butler is the author of 10 other novels, including Parable of the Sower series. She’s the recipient of many awards, including the MacArthur Genius Award. Her latest book is called Fledgling.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: About a vampire?

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Yeah, it was kind of an effort to do something that was more lightweight than what I had been doing. I had been doing the two Parable books—Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents—and they were what I call cautionary tales: If we keep misbehaving ourselves, ignoring what we’ve been ignoring, doing what we’ve been doing to the environment, for instance, here’s what we’re liable to wind up with. And I found that I was kind of overwhelmed by what I had done, what I had had to comb through to do it. So, eventually I wound up writing a fantasy, a vampire novel.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But you also tell a lot about vampires themselves. The Ina people? Could you talk a little about that?

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Well, of course, I made them up. But one of the things I discovered when I decided to write a vampire novel was that most writers these days who write about vampires make up their own, and it really is a kind of a fantasy matter. You make up the rules, and then you follow them.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us about your protagonist in Fledgling, who this vampire is.

OCTAVIA BUTLER: OK, she is a—

AMY GOODMAN: “She” is an operative word, I think, to begin with.

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Oh, OK. She’s a young girl. You’re right. Most vampires, I’ve discovered, are men, for some reason. I guess it’s because Dracula, people are kind of feeding off that. She has amnesia. She’s been badly injured. She’s been orphaned. And she has no idea what she is or who she is. Turns out she’s the first black vampire because of her people’s desire for a 24-hour day and her female ancestors’ discovery that one of the secrets of the 24-hour day is melanin.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean?

OCTAVIA BUTLER: It helps to have some protection from the sun, so her people managed to genetically engineer her. These vampires are a different species. They are not vampires because somebody bit them. So, they—she is genetically engineered to be quite different from her own people. On the other hand, she’s not human. So she’s kind of alone, to begin with. It’s just that by the time we meet her, she is very much alone, because she knows nothing. She’s 53 years old, and all those 53 years have been taken from her.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: How did you first start writing science fiction? You grew up in Pasadena?

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Mm-hmm.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And how did you first become attracted to that type of writing?

OCTAVIA BUTLER: Oh, I think I loved it because—well, I fell into writing it because I saw a bad movie, a movie called Devil Girl from Mars, and went into competition with it. But I think I stayed with it because it was so wide open. It gave me the chance to comment on every aspect of humanity. People tend to think of science fiction as, oh, Star Wars or Star Trek. And the truth is, there are no closed doors, and there are no required formulas. You can go anywhere with it.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Octavia Butler. Her latest book is Fledgling, wrote the Parable series. As Katrina was happening, in the aftermath of Katrina, a lot of people were talking about Octavia Butler and how the Parable series made them think about that. Explain.

OCTAVIA BUTLER: I wrote the two Parable books back in the '90s. And they are books about, as I said, what happens because we don't trouble to correct some of the problems that we’re brewing for ourselves right now. Global warming is one of those problems. And I was aware of it back in the ’80s. I was reading books about it. And a lot of people were seeing it as politics, as something very iffy, as something they could ignore because nothing was going to come of it tomorrow.

That and the fact that I think I was paying a lot of attention to education because a lot of my friends were teachers, and the politics of education was getting scarier, it seemed to me. We were getting to that point where we were thinking more about the building of prisons than of schools and libraries. And I remember while I was working on the novels, my hometown, Pasadena, had a bond issue that they passed to aid libraries, and I was so happy that it passed, because so often these things don’t. And they had closed a lot of branch libraries and were able to reopen them. So, not everybody was going in the wrong direction, but a lot of the country still was. And what I wanted to write was a novel of someone who was coming up with solutions of a sort.

My main character’s solution is—well, grows from another religion that she comes up with. Religion is everywhere. There are no human societies without it, whether they acknowledge it as a religion or not. So I thought religion might be an answer, as well as, in some cases, a problem. And in, for instance, Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, it’s both. So I have people who are bringing America to a kind of fascism, because their religion is the only one they’re willing to tolerate. On the other hand, I have people who are saying, “Well, here is another religion, and here are some verses that can help us think in a different way, and here is a destination that isn’t something that we have to wait for after we die.”

AMY GOODMAN: Octavia Butler, could you read a little from Parable of the Talents.

OCTAVIA BUTLER: I’m going to read a verse or two. And keep in mind these were written early in the ’90s. But I think they apply forever, actually. This first one, I have a character in the books who is, well, someone who is taking the country fascist and who manages to get elected president and who, oddly enough, comes from Texas. And here is one of the things that my character is inspired to write about this sort of situation. She says:

Choose your leaders with wisdom and forethought.

To be led by a coward is to be controlled by all that the coward fears.

To be led by a fool is to be led by the opportunists who control the fool.

To be led by a thief is to offer up your most precious treasures to be stolen.

To be led by a liar is to ask to be lied to.

To be led by a tyrant is to sell yourself and those you love into slavery.

And there’s one other that I thought I should read, because I see it happening so much. I got the idea for it when I heard someone answer a political question with a political slogan. And he didn’t seem to realize that he was quoting somebody. He seemed to have thought that he had a creative thought there. And I wrote this verse:

Beware:

All too often,

We say

What we hear others say.

We think

What we’re told that we think.

We see

What we’re permitted to see.

Worse!

We see what we’re told that we see.

Repetition and pride are the keys to this.

To hear and to see

Even an obvious lie

Again

And again and again

May be to say it,

Almost by reflex

And then to defend it

Because we’ve said it

And at last to embrace it

Because we’ve defended it

AMY GOODMAN: On that note, we’ll have to leave it there, but we’ll continue it online at democracynow.org. Octavia Butler.

Media Options