Guests

- Thomas Breuerhead of the Climate and Energy Unit for Greenpeace Germany. He is part of a field team of radiation monitors in Japan.

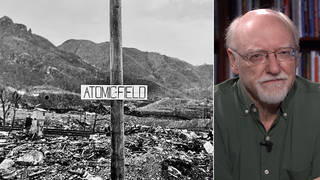

Japan has raised the severity rating of its nuclear crisis from 5 to 7, the highest level, matching the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. We go to Tokyo for an update from Thomas Breuer, head of the Climate and Energy Unit for Greenpeace Germany and part of a field team of radiation monitors in Japan. He notes that unlike Chernobyl, the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is in a densely populated area. “We warned the government that there are a lot of cities and villages outside the 20-kilometers evacuation zone where the radiation levels are so high that people need urgently to be evacuated, especially children and pregnant women, because they are the most vulnerable part of the population to radiation,” says Breuer. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Japan has raised the severity rating of its nuclear crisis to the highest level, matching the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The level 7 rating signifies a major nuclear accident. At a news conference today, an official from the Tokyo Electric Power Company said, quote, “The radiation leak has not stopped completely, and our concern is that it could eventually exceed Chernobyl.”

For an update on the situation, we go to Tokyo. Thomas Breuer, head of the Climate and Energy Unit for Greenpeace Germany, joins us by Democracy Now! video stream. He’s part of a field team of radiation monitors in Japan.

Thomas Breuer, Greenpeace has been talking about the situation being more severe for a number of weeks now. Explain what it means for Japan to lift the crisis level from 5 to the very highest, to 7.

THOMAS BREUER: Yeah, Amy, maybe first of all, the idea from the INES scale, which was introduced after the Chernobyl accident, is exactly to inform the public in a timely manner. And Greenpeace has done calculations with scientists already three weeks ago, where we figured out that this accident is in a scale 7 accident. And we are wondering why the government of Japan needs three weeks to come to the same conclusion, especially because they must have way better data than we have. So, what it means now, they wasted three weeks of not informing the public about the real, real risks of this accident.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, though, talk about what 7 means. I mean, we’re talking about the continuing nuclear catastrophe that’s unfolding in Japan being equal to the worst nuclear disaster in history: Chernobyl.

THOMAS BREUER: So, from my point of view, it is not equal to Chernobyl, it is way worse, because we are, like, facing three reactors totally, or partly, destroyed. A fourth reactor has a problem with the spent fuel, which had a huge explosion. And when we did the calculations like three weeks ago, we figured out that, depending of course about the spread between the three reactors, each of these reactors could be rated as a INES scale 7 accident, because the INES scale does not even consider a multiple accident, what we are seeing here in Fukushima. So, that is way worse than what we’ve seen in Chernobyl. Another point there, which is very important, so in Chernobyl was more or less rural area around the reactor. But Fukushima is in a densely populated area, so millions of people are living around it. So, even that makes it worse and more difficult to manage.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you think Japan needs to do right now?

THOMAS BREUER: So, there are urgency measures. So, it is now clear that, since we did our field research, we warned the government that there are a lot of cities and villages outside the 20-kilometers evacuation zone where the radiation levels are so high that people need urgently to be evacuated, especially children and pregnant women, because they are the most vulnerable part of the population to radiation. And so, they have to do that now. They have to screen the whole Fukushima area, where there are other hot spots which need to be evacuated.

And then they have to — what they haven’t done so far — really, really explain to people who are still living there what to do, how to behave. So, we were approached from a lot of farmers during our field work, asking us whether we can come to their fields and do food testing, because they have no idea whether they still can eat the food or sell it or whatsoever. So, that’s a very difficult situation. We have been in Fukushima City. That’s a city with 340,000 inhabitants, and we found very high levels of radiation in the city all over again. But life seems to be like, on the surface, like normal life, and it has to do with the fact that the government did not put out information, how to behave, what to do. So people are really left alone with this accident, which wasn’t caused by them.

AMY GOODMAN: Thomas Breuer, you’re in Tokyo right now, but you head the Climate and Energy Unit for Greenpeace Germany. You’re speaking to me in the United States, where our president, President Obama, is really pushing a nuclear renaissance for the first time in decades, pushing for the building of nuclear power plants. Talk about the response around the world to what’s happened in Japan.

THOMAS BREUER: So, it’s not understandable how one can push for nuclear renaissance, especially if you dig into the whole industry. It’s, first of all, not compatible with democracy, because the open society, as we are living in, they cannot deal with nuclear, because they are so vulnerable to terrorism and to accidents that there will be always a clash with democracy at the end of the day. And so, Obama should look what is happening in Germany. So, Angela Merkel, even though she used to be quite pro-nuclear, as well, after the accident, she understood the real risks of nuclear power plant, and she closed down immediately eight of the 17 reactors in Germany. And I think that’s a responsible way to deal with nuclear: it has to be closed down.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you, Thomas Breuer, for joining us, head of the Climate and Energy Unit for Greenpeace Germany, part of the field team of radiation monitors in Tokyo, Japan.

Media Options