This week marks 80 years since the first use of nuclear weapons in war, when the United States dropped a pair of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed in the bombings. Many died instantly, and many others died more slowly from severe burns and radiation sickness. Some estimates put the combined death toll over 250,000 killed. We speak with veteran journalist Greg Mitchell, whose new documentary, streaming at PBS.org and airing on PBS, reexamines a remarkable episode in the U.S. occupation of Japan after the end of World War II, when the U.S. military held an all-star football game in the ruins of Nagasaki, reflecting what Mitchell calls a “careless” and “heartless” U.S. attitude. The Atomic Bowl is “horrifying history” that is worth reexamining, says Mitchell, because “there is not a real taboo on using nuclear weapons, because so many historians, so many in the media continue to support the use of the atomic bomb against Hiroshima and even Nagasaki.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Eighty years ago today, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb in the world on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Today, a memorial service was held at the Hiroshima Peace Park to remember.

Three days after Hiroshima, the U.S. dropped another atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed in the bombings, many instantly, many more slowly from severe burns in what would come to be understood as radiation sickness, or bomb sickness. Some estimates’ combined total was at least a quarter of a million people dead.

Today, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba urged all countries to make efforts towards nuclear disarmament.

PRIME MINISTER SHIGERU ISHIBA: [translated] We must not repeat the tragedy that was brought upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is our country’s responsibility, as the only nation that has suffered atomic bombings, to uphold the Three Non-Nuclear Principles and lead the global initiative for a world without nuclear weapons.

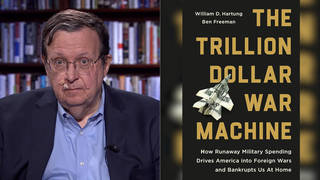

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we spend the rest of the hour with Greg Mitchell, former editor of Nuclear Times magazine who’s written extensively about the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His past books include The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood and America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, also the book Hiroshima in America and Atomic Cover-Up. Greg Mitchell is also a filmmaker. He has a new documentary, now streaming on PBS.org, airing on local stations, called The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero — And Nuclear Peril Today. It’s a companion to his new book of the same name. This is the trailer for the film, which is narrated by Peter Coyote.

NEWSREEL: Admiral Halsey heads up Pasadena’s colorful Tournament of Roses Parade. It’s the 57th annual observance of the event.

PETER COYOTE: New Year’s Day. Americans get ready to enjoy the traditional college football bowl games. In the biggest contest, Southern Cal plays Alabama in the Rose Bowl. A dozen other games draw wide attention. But the most unique bowl game was played that day across the Pacific in Japan. It featured U.S. Marines who were part of the hundreds of thousands of American forces occupying the country since Japan’s surrender in September. Among the stars in the game was a quarterback who had recently won the Heisman Trophy and a legendary pro-football running back.

But it was the site of the game that would prove disturbing: on a makeshift gridiron near ground zero in Nagasaki, where tens of thousands had been killed by the atomic bomb less than five months earlier. Many of the players and other U.S. servicemen in Nagasaki had been exposed to lingering levels of radiation for months. Some would later complain of cancer or other diseases that can be caused by radiation. Why was this game played at this site, and then disappeared from history for decades? And why does the story of the atomic attack on Nagasaki provide so many warnings and lessons for today?

AMY GOODMAN: The trailer for The Atomic Bowl.

For more, we’re joined by Greg Mitchell, director of this new PBS film and a book of the same title. Greg, today is August 6. Eighty years ago, the first atomic bomb in the world was dropped on Hiroshima, three days later on Nagasaki. This book calls attention to what you call the second forgotten or overshadowed bombing. President Obama famously went to Hiroshima, though not to Nagasaki. Oppenheimer film had maybe two short mentions of Nagasaki. Talk about this, what many would see as a sacred period, because so many hundreds of thousands of people were killed between these two days 80 years ago.

GREG MITCHELL: Yes. Well, you know, as you mentioned, Nagasaki is — when I was at Nagasaki — they refer to themselves as the “inferior” atomic bomb city, because so little is paid attention to them to this date. So, I’ve always, in my many years of writing about this and making films, tried to pay special attention to Nagasaki. So I was very happy to make this film, which focuses on the use of the bomb in Nagasaki and the aftermath, the U.S. occupation of the atomic cities, which has been covered very, very little over the years compared to the European occupation, and then leading up to the, we might say, bizarre, surreal, horrifying decision to hold an all-star U.S. military football game, not only in Nagasaki, but on a field in front of a school where 175 students and teachers had been killed by the bomb, so —and then, of course, the aftermath of that and the lessons for today from that. But it is revealing, in many ways, that the U.S. would feel, even after the killing of all the civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that they could still hold a sporting event on a — not only in Nagasaki, but on a field where so many had died.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in terms of the soldiers that were exposed, could you talk about the battles of some of them to have the military recognize the American soldiers who participated in that game?

GREG MITCHELL: Yes. Well, you know, there were hundreds of thousands of Americans who went into Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and they were given very little warning on what they might find there. They worked in the ruins. They cleared the ruins. They were given radiation devices that many said didn’t work. And so, many of them complained right away and in years after about serious health defects, later developing cancer and leukemia and so forth, that the military did not recognize for decades. And it was only as late as the 1990s that they began to get compensation and some attention for what had happened there. And it was, you know, a real struggle to do that. And, of course, we see it today even with the downwinders, the victims of the U.S. testing in Nevada and Utah and so forth, who had had to fight so hard to get any kind of recognition and compensation for their — the effects on them, you know, from the fallout that they suffered from.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to this new film that you have out at PBS.org, The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero — And Nuclear Peril Today.

PETER COYOTE: Hours before the Nagasaki bombing, the Soviet Union, as promised, declared war on Japan, which President Truman, back in July, had said meant certain defeat for the enemy, even without use of an atomic bomb. Truman was reportedly surprised to learn of the second bombing. After Nagasaki, he ordered that no further atomic bombs be used without his expressed approval. Truman warned that if he ordered a third atomic attack, another 100,000 would die, and, he said, he didn’t want to kill, quote, “all those kids.” When they learned of the Hiroshima attack, scientists at Los Alamos generally expressed approval, but many of them, including Robert Oppenheimer, took the Nagasaki bombing quite badly. Observers said that Oppenheimer appeared anxious, depressed, and even, one reported, a nervous wreck.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero — And Nuclear Peril Today. How is it possible that for — well, first, the decision to drop the atomic bomb, but then the second one three days later, when, as you point out in the film, Truman — they understood that Japan was just about to surrender. Was it to test the two different kinds of nuclear bombs?

GREG MITCHELL: Well, there’s been a lot of theories about this, that some people believe in the testing notion or the notion we were sending a signal to the Soviets, who were about to enter the war. But, you know, maybe the lesson for today is that the Nagasaki attack, which few people understand, was almost automated. You know, there was no separate decision to drop the bomb on Nagasaki. Truman was coming back from Potsdam, and the order was simply for them to roll off the assembly line and used when ready. And General Groves stepped in, and it was his goal to use it as soon as possible. And so the bomb was used almost automatically, without a sense of pausing. And, you know, as that clip shows, Truman was surprised that it had been used, and when he heard that it had been used, he put a stop for a third weapon.

But the use of the second bomb shows how careless, heartless the U.S. was about the use of the bomb, and, again, showing up with the football game, that’s, you know, in the film, where they just even, four months later, felt they could have this game. A few months after that, they held a Miss Atomic Bomb beauty contest in Nagasaki with the Japanese women. So, it was — there was no apparent sense of shame, or maybe we should not draw attention to what we did there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But there was an attempt to hide from the world the real catastrophe, the human lives that had been lost. I think it was Wilfred Burchett, the Australian foreign correspondent, who got to Hiroshima about a month after the bombing. But could you talk about the efforts to suppress information about what had happened, to other parts of the world?

GREG MITCHELL: Yes, I did, in my previous book, Atomic Cover-Up, and my previous PBS film, also called Atomic Cover-Up, looked at the decadeslong suppression of the most important footage shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, first by a Japanese newsreel team and then by an elite U.S. military crew that shot the only color footage there. And, you know, as I detail then, that footage was buried and suppressed for decades and not shown to Americans or the world until many, many years later. So, this suppression of what we actually did there covered all sorts of things, from, you know, newspapers and the press to film footage and even what Hollywood was allowed to or chose to show.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk about that in the context of the current times, where all the nuclear test treaties are being disassembled by the participants and where we’re seeing efforts to modernize the nuclear program in the United States?

GREG MITCHELL: Yes, well, you know, the famous Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, they moved it the closest to midnight it’s ever been this year, because of things like that.

You mentioned modernize. You know, one thing that they’ve — we have famously modernized is we now have bunker-busting nuclear weapons. And I myself was extremely worried when Trump decided to use the conventional bunker buster for the first time ever on the Iranian nuclear sites six weeks ago. And it did, you know, lead to — or, it was one of the things that led to the ceasefire. But my fear was that Trump, trigger happy, and the people he’s surrounded by, if that hadn’t worked, that he might have been tempted or might have actually used one of these new, modern, smaller nuclear bunker busters. So, you’re right, the modernization has the potential, and the problem is that they may be more likely to be used, because they are seen as smaller and not as — perhaps not as earth-shattering.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg, you can’t help but think, when you watch the trailer to the film, when you just show the moonscape, both in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the comparison to what we’re seeing in Gaza right now.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah, I’ve called Gaza “Nagasaki in slow motion.” And you do — the photos do look remarkably similar in some places. And in fact, you know, again, few people know that, unlike Hiroshima, which did have a major military base, even though most of the people killed in Hiroshima were civilians, Nagasaki had no major military base, and almost all of the casualties in Nagasaki were civilians.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, I want to follow up on Juan’s point about the cover-up, about Wilfred Burchett, this great Australian journalist, who, although the U.S. said Japan’s off limits after Hiroshima, he makes his way in a train for something like 20 hours, gets there, sees this moonscape, the horror and people’s skin melting off their faces. And he sits down in the rubble and taps out the words on his Hermes typewriter, “I write this as a warning to the world.” He didn’t have words. He said, “I’m seeing a kind of bomb sickness,” to which the United States and The New York Times, interestingly, you pointed out —

GREG MITCHELL: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: We just saw a picture of Groves, Oppenheimer and William Laurence —

GREG MITCHELL: Right, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — who wrote for the Times, and the Pentagon, though we didn’t know this —

GREG MITCHELL: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — saying that — and the U.S. government saying that the bomb sickness was simply Japanese propaganda.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah, yeah. Groves, Leslie Groves, played by Matt Damon in the Oppenheimer film, said that he even heard it was a rather pleasant way to die. And, you know, I mean, you mentioned Burchett, but in Nagasaki, George Weller was a reporter, was the first U.S. reporter into Nagasaki, and he sent the same sort of dispatches —

AMY GOODMAN: For AP.

GREG MITCHELL: For the Chicago — Chicago newspapers, and it would have been syndicated. But he sent it in. He sent it to MacArthur’s office in Tokyo, and they never appeared for a decade. They were killed. And that was in Nagasaki. So, the same thing that happened in Hiroshima happened in Nagasaki: another famous reporter, and his material was killed.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what are you hoping that folks will take away from the this film of yours?

GREG MITCHELL: Well, I’ve been writing and doing films for 40 years now, and, of course, the hope is always that it alerts people to the current dangers, the current threats. It’s not just a piece of history. It’s very interesting history. It’s horrifying history. But it’s also the lessons for today and the warnings for today, which includes a possible use of nuclear weapons again today. We have AI, which is now entering our system, our nuclear systems, which is very scary. And we have that, in my view — the reason for even returning to Hiroshima and Nagasaki is, in my view, there is not a real taboo on using nuclear weapons, because so many historians, so many in the media continue to support the use of the atomic bomb against Hiroshima and even Nagasaki.

AMY GOODMAN: And now Trump wants to put a nuclear plant on the moon in the next few years.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah, right, nuclear reactor on the moon. So, to me, there’s certainly no nuclear taboo, as far as I can see, and that makes it scary for possible use again. And that’s the reason to keep returning to — may seem like history, but it’s very, very, very timely today.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg Mitchell, we want to thank you so much for being with us, director of the new film, now streaming on PBS.org, The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero — And Nuclear Peril Today. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options