Guests

- Stuart HanlonSan Fransisco-based criminal lawyer who began working on Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt’s case when he was a law student and stayed for 23 years until Pratt won his freedom in 1997.

- Ed Boyerwas a Los Angeles Times reporter for 20 years. He began writing about Geronimo Pratt’s case in the early 1990s. He covered the hearings and Pratt’s release.

We look at the life of former Black Panther, Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, who died in Tanzania on Thursday. In 1972, Pratt was wrongfully convicted of the murder of Caroline Olsen for which he spent 27 years in prison, eight of those in solitary confinement. He was released in 1997 after a judge vacated his conviction. The trial to win his freedom revealed that the Los Angeles Black Panther leader was a target of the FBI’s counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO. We play an excerpt of a Democracy Now! interview with Pratt and one of his attorneys, Johnnie Cochran, Jr., in 2000. We also speak with his friend and former attorney, Stuart Hanlon, and with Ed Boyer, the Los Angeles Times reporter who helped expose his innocence. “The FBI followed Geronimo every second, almost, of his life, and they knew he was in Oakland at the time of the homicide,” says Hanlon. “When we started litigating this, rather than turning it over, for the first time anyone could remember FBI wiretaps disappeared. And of course they knew where he was. It didn’t matter what the truth was, because he was the bad guy, and the truth had to take second place, even in the courtroom.” Pratt ultimately won a $4.5 million civil rights settlement against the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The former Black Panther leader Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt died Thursday at the age of 63 in a village in the East African country of Tanzania.

In 1972, Pratt was wrongfully convicted of the murder of Caroline Olsen. He spent 27 years in prison, eight of those in solitary confinement. He was released in 1997 after a Reagan appointee, a judge, vacated his conviction. Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, his family and supporters always maintained he was targeted and framed by the FBI and the L.A. Police Department because of his activity in the Black Panther Party. Two years after his release, Pratt won a $4.5 million settlement of his civil rights case against the FBI and LAPD. The FBI’s share of $1.75 million marked one of the few times in its history it was forced to admit culpability in a case of false imprisonment.

Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, born Elmer Pratt, was a Louisiana native, decorated Vietnam vet who served in the Army’s 82nd Airborne.

Before we turn to our guests, I’d like to play part of a radio interview I did with Geronimo Pratt in 2000, three years after he was released from jail. We were also joined in WBAI’s studios in New York for this conversation by one of Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt’s attorney’s, Johnnie Cochran, who died in 2005.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I grew up in segregation, and we had to deal with the terror from the Klan violence and, you know, other forms of ignorance from those peoples. But growing up in that kind of environment instilled in me a pride of — or a sense of nationalism, that we can govern ourselves, and we can protect ourselves, and we didn’t need to be with anyone who didn’t want to be with us. So, out of that, I was part of a group that was selected by the elders to get military training, to come back to the community, you know, and help protect it, relieve the old soldiers. It just so happened that when I was selected, Vietnam was happening, and I ended up in Vietnam and survived that, two tours, or two and a half. And when I came back, it was shortly after Martin Luther King was assassinated, so the black nation was more or less at one now with the — just being fed up. And everyone was saying, “Look, we have to do something.” So us young militant types were employed quite extensively throughout the nation. And so, this is how I ended up in these cities contributing what little I could contribute.

AMY GOODMAN: And you got involved then with the Black Panther Party?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, with various organizations, including the Black Panther Party.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how did you end up in a courtroom being tried for the murder of Caroline Olsen? She was killed playing on a Santa Monica tennis court with her husband in 1968. You were caught and charged when?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I was arrested two years after that, in 1970, in Dallas, Texas, where I was instrumental in helping to organize the first Black Panther chapter there in Dallas, Texas, and other parts of the South. I was charged because of a conspiracy by the government that was led by the Hoover — what we call the Hoover-Nixon regime, which was an illegal conspiracy directed against the entire left, entire movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnnie Cochran, how did you get involved with Geronimo’s case?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: I was appointed by the court, by Judge Kathleen Parker, to represent Mr. Pratt in the murder case. I had met him and had sat alongside him in another case, the so-called Panther shootout case that took place in 1970, ’71, in L.A., was then the longest trial ever. And all the Panthers were pretty much acquitted of all the charges in that, and it was a bogus case. The court then appointed me to represent him in the tennis court murder case.

AMY GOODMAN: And what happened in that first trial?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Well, it was an amazing trial. I mean, we came in there knowing and believing strongly that Geronimo Pratt was innocent. We sought to set out to prove that innocence, to establish an alibi. We ran into some problems in getting other Panther members to come and establish the alibi. Mr. Pratt was in Oakland at the time of these killings in December of 1968. None of the other —- none of the Panthers who were affiliated with or aligned with Huey Newton would come. So, Kathleen Cleaver was in exile -—

JUAN GONZALEZ: And that was because he had already been expelled from the Panther party.

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Mr. Pratt had been expelled, and further, that the FBI had infiltrated so much that they had inculcated this kind fear and distress and whatever. They wouldn’t let him come testify. So we got Kathleen Cleaver to come back, and she was a great witness. She couldn’t pin it down as much as we wanted to, but we still thought we won the case. Jury stays out like 12 days or more, and they’re hopelessly deadlocked. But they end up convicting an innocent man. And it was all of the things we didn’t see that took place which caused that, that defeat.

Mr. Pratt would always say, “They are out to get me there.” And I would always say, “Well, who do you mean by 'they'? What do you mean by 'they'? Who is this 'they'?” And of course, he was right. As I said, I learned a lot from representing Mr. Pratt, you know, that a little paranoia is healthy, that even paranoid people have real enemies. And of course, he was right, that it was “they.” It was the FBI. It was the counterintelligence program.

And Amy, how we found out this out was through the good offices, really, of Stuart Hanlon. In the intervening years after the conviction, through the Freedom of Information Act, we were able to find out a number of things, that this man, Julius Butler, who was the star witness for the prosecution, who got on the stand and said that Mr. Pratt confessed to him, and was asked by me, “Are you now, have you ever been, an informant for the FBI or any other agency?” And he said, “No.” He said, “No,” unequivocally “no.” He lied. At that point, he said that he informed 33 times. And, in fact, he was an informant for the LAPD and the L.A. County DA’s office. He was their confidential informant. They had done that. They had wiretapped our phones. They had informants in the defense environs, meaning that somewhere in our offices they knew everything we were going to do. They had failed to give us Brady material, that is, exculpatory material, where the husband of this lady who was shot had positively identified two other people. They kept that from us. They did all these things in an effort to neutralize — which meant kill, destroy, lock up forever — Geronimo Pratt, at the behest of J. Edgar Hoover.

AMY GOODMAN: Geronimo, before you were set free, 26 years and seven months after you went to prison, you were in solitary for eight years.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: We can say that, but what does that mean? What is life like in solitary? Where were you kept?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I was kept in the hole in San Quentin and Folsom. I started in the hole in Dallas, Texas, where I was busted, and then on to the holes in the Los Angeles County jail, which is like nightmares, when you’re talking about the holes in Texas and L.A. County, the old county jail, and then on to the holes in state prisons. But what it means is that this country tortures people. And right now, Hugo Pinell is going into his 27th year in the hole. Woodfox and Wallace and King, who are in Angola State Prison in Louisiana, are going into their 23rd year — year — in the hole. So, when you’re talking about eight years in the hole, and you look at this ongoing today, it’s hard for me to even talk about those eight years because it’s happening right now.

AMY GOODMAN: How many hours a day are you kept in this single cell?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Twenty-four hours a day. And then, after the second year, it became 23 and a half. They would let you out for half an hour.

AMY GOODMAN: To those who say that the system has proved that it works by, ultimately, you being exonerated, what do you say?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: I say that that’s not a — that’s the evidence to the contrary, that it doesn’t work too well. All of my — seven years of my twenties, every minute of my thirties, every second of my forties were taken away from me. If that’s a system working, then I think something’s wrong with your thinking.

AMY GOODMAN: Geronimo ji-Jaga, born Elmer Pratt, speaking in the studios of WBAI with Juan Gonzalez and me, along with one of his attorneys, the late Johnnie Cochran. Yes, Johnnie Cochran, of O.J. fame, said that this case, the case of Geronimo ji-Jaga, was the most important of his life, and the happiest day was the day that he was released.

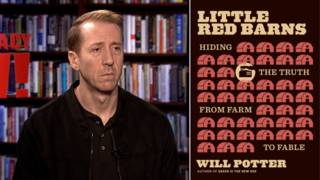

Also in that studio that day and joining us today from San Francisco is Geronimo ji-Jaga’s friend and former attorney Stuart Hanlon. Hanlon is a criminal lawyer who began working on Pratt’s case when he was a law student and stayed for 23 years until Pratt won his freedom in ’97.

And we’re joined on the phone from Los Angeles by Ed Boyer, who began writing about Pratt’s case in the early ’90s for the Los Angeles Times, where he was a reporter for 20 years, now retired.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Stuart Hanlon, let’s go to you first. The news of the death of Geronimo ji-Jaga — you remained his friend to the end. He died in Tanzania. He was living there?

STUART HANLON: Right. He died — he had just — I think he had left about three weeks before from Louisiana, and he had a great trip out here in California. And he seemed terrific. And it was a real shock, obviously. He just had such a great time when he was out in California with his daughter, seeing me and some other people. But, you know, life is short.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, first, our condolences to you and to his family, who he was living with in Tanzania. In a nutshell, describe this case. And especially for young people, describe what COINTELPRO is, the counterintelligence program, and how a Reagan-appointed attorney — a Reagan-appointed judge ultimately overturned the conviction of Geronimo ji-Jaga, the jury never having known that the person who pointed the finger at Geronimo ji-Jaga falsely was a police and FBI informant.

STUART HANLON: I think the place to start is the question that you guys asked Geronimo years ago: do you think it proved the system works because you won? And Johnnie, at one point — it’s one of the few differences he and I had, and he said the same system that locked up Geronimo let him free. Well, the system doesn’t work. And if it took — as Geronimo pointed out, it took 27 years of his life to free an innocent man.

And what people should understand, and which I think we kind of understood back then but not to the extent it was proven, is that our government and your state government, because it is the FBI with the president, local law enforcement in Los Angeles, district attorneys, conspired to convict somebody and lock them up and have them face the death penalty, because of their political beliefs and affiliations, that back in the '60s and early ’70s the Panthers were considered by J. Edgar Hoover and many others, especially in the white community, the number one threat to the safety of America. And imagine that, that we felt that a group of young African Americans, probably less than a thousand throughout the country, were the number one threat to our internal safety. And because of that, these law enforcement people and judges and district attorneys felt that the ends justified the means to get rid of them, by any means necessary. And we've learned that Fred Hampton was murdered, another Panther, in Chicago, and Geronimo was framed.

And people say, “How do you know he was framed? It was just some technicality.” And I think the best image is that Julio Butler was asked by Johnnie on a number of occasions, “Were you an informant for any agency?” And he said, over and over, “No.” And as it turned out, and I think what got Judge Dickey, is that he was an informant not just for the FBI, but for the L.A. Police Department and, finally, for the L.A. district attorney’s office. And these three agencies sat in court, because the FBI was there, and let this man lie and commit perjury to convict somebody. That’s not a technicality. That’s a breakdown of our criminal justice system. That’s the highest level of people involved letting someone commit perjury because they don’t like him and like his beliefs.

And I think the last question you asked, Amy — how does this — what does this say to people today, young people, like Geronimo and I were 47 years ago? And even Johnnie was pretty young back then. That paranoia is healthy, that now our new enemy may not be the Black Panther Party or African-American groups, but the new enemy could be Mideastern people or Muslims. And we demonize them as the Panthers were demonized, and then we justify trials without juries, trial without — you know, in military courts. We justify setting up military courts in Cuba, in Guantánamo. We justify all these things in the name of protecting our country. And what we don’t understand is our country falls apart when we do these things. And the legal system falls apart when we let these things happen. And that’s the ultimate — not personal story of Geronimo, but the political story, I think.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the remarkable things is that the FBI was so closely monitoring Elmer Pratt, Geronimo ji-Jaga, as leader of the Black Panther — one of the leaders of the Black Panther movement, that they had repeated wiretaps of him. They knew where he was, didn’t they? That night, for example, when Caroline Olsen was killed on the tennis court, this young woman who, with her husband, had gone to play tennis?

STUART HANLON: Well, you know, we were — Geronimo, when he was here, he and I were looking through old boxes of COINTELPRO documents. There were thousands and thousands just on his case. And I just recently, after Geronimo died, talked to an investigator who first found the wiretaps. Investigators and an ex-FBI agent, Wesley Swearingen, found the wiretaps. And by the time we got to the case, they had been destroyed. But the FBI followed Geronimo every second, almost, of his life, and they knew he was in Oakland at the time of the homicide. And when we started litigating this, rather than turning it over, for the first time any could remember FBI wiretaps disappeared. And of course they knew where he was. It didn’t matter what the truth was, you see, because he was the bad guy, and the truth had to take second place, even in the courtroom. But yeah, Amy, they certainly knew where he was, and they knew what he was about, and as did many other Panthers. I mean, they knew where they all were. It was amazing the amount of time, money and effort was put into monitoring this small group of political activists.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re also, in addition to Stuart Hanlon, joined by Ed Boyer, longtime Los Angeles Times reporter, now retired, but he did write the piece on Geronimo ji-Jaga when he died on Thursday. Ed, talk about how you first came to this story. Your reporting was instrumental ultimately in having Geronimo ji-Jaga exonerated and freed.

ED BOYER: Well, Amy, I saw a very short story in the L.A. Times towards the end of the week pointing out that Jim McCloskey, who runs Centurion Ministries, was was getting involved and investigating the case. And that was my first entrée, because McCloskey had just had a successful case in Los Angeles County. Clarence Chance and, I believe, Benny Powell, they were released after 17 years in prison. So I began reading our old clips. And what I found amazing was that going back to 1979, from Freedom of Information requests, they turned up all of this evidence showing that Julius Butler had been an informant. And during Geronimo’s original trial, his prosecutor said, “This case boils down to does the jury believe Julius Butler? If they believe Butler, the case is over.” So they built their whole case around Butler. And less than seven years afterwards, there was all this Freedom of Information material showing that Butler had lied that long ago. And that’s when I began reporting. And it was stunning to me to learn that Butler was chairman of the board of one of the most prominent and one of the most outstanding African-American congregations in Los Angeles, First AME Church. So I began my reporting there.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what you uncovered through this period and how ultimately Geronimo ji-Jaga was freed.

ED BOYER: Well, I think he was ultimately freed because of Stuart Hanlon and Johnnie Cochran. The very people who had run him as an informant sat there during the habeas corpus hearing and pointed out, yes, he was my informant in this circumstance and this circumstance. They detailed, chapter and verse, how he had been their informant. There was no getting around it at that point.

But I just continued to report. I found one of the original jurors, who told me that had she and at least two other jurors, had they known that this guy was an informant, they never would have voted for conviction. And the thing that turned them, however, was that there was this odd situation with a Polaroid photograph. I talked to Cochran about this, and Stuart probably talked to him more than I did, that this photograph was kind of throwaway evidence. Witnesses had described Pratt as — had described the shooter, rather, as clean-shaven. But Pratt had always had a goatee. And towards the end of the trial, my understanding is Johnnie introduced this Polaroid photo of him with a goatee, and he could not have grown that between the time of the murder in December of ’68 and Christmas of ’68, when the photo was taken. The prosecution came right back with an expert from Polaroid saying the film used in this photograph was not even available until some six months later. And that was very damaging, according to the juror I spoke to.

But I just continued to find people who were involved, continued reporting the story, whatever little leads I could. I mean, this is how I met Stuart Hanlon. And I got an education from him, of course.

AMY GOODMAN: Stuart Hanlon, can you talk about the judge who ultimately overturned the conviction?

STUART HANLON: Judge Dickey — you know, we were in Los Angeles, a bunch of lawyers. It was Johnnie and me and a bunch of other people — Mark Rosenbaum of the ACLU, Julie Drous in San Francisco, Robert Garcia. It was a lot — and we thought we’d get a liberal judge in L.A. And the whole judge — the whole bench recused themselves, because, like I said, we can’t hear the case because the ex-DA who we were attacking was now a judge. So we got sent to Orange County, and everybody said, “Oh, you’re behind the orange curtain. You’re finished.” We’re going to get — and then we get this Republican judge appointed by Reagan, and we thought we were over. And what we didn’t understand is we found a true conservative who believed in the Constitution. And every time we walked into court, we had to pledge allegiance to the flag, which was unusual in courthouses at that point. But it set a tone of we were going to follow the rules.

And I think he was really moved by the evidence. I think Johnnie Cochran had an incredible presence in that courtroom. And Judge Dickey was offended at the deepest place as a good judge can be at how justice was turned on its head. The things Ed was talking about, that these cops came in and this young investigator came in for the DA, and they proved Butler was an informant. I mean, the DA said, the judge said, “I didn’t know” — this Judge Richard Kalustian, who was the DA. And then this young investigator came in and said, “Here’s our informant file from 1970. And Julius Butler, I found it by looking under B.” And you could see in the courtroom how it just fell apart. And it wasn’t just Butler. There were so many other things that showed Pratt was innocent. But by the end, I was watching last night a video of Geronimo getting bail, and Johnnie said, “How that $1,000 for each year? Let’s set it at $25,000.” And Judge Dickey literally had tears in his eyes when he granted it. He was moved by Geronimo, this ex-Vietnam vet. And the proof that he was framed by the country, Dickey believed it. I think it shook the judge to his core to see what had occurred.

I just want to say one thing, Amy, in terms of what Ed did. It was amazing, the media. Ed and another reporter from the Times before Ed, Austin Scott, they made this a national story, you know? They made this something that couldn’t go away. And, you know, the power of the press and what Ed Boyer did, and Austin Scott, was truly amazing in moving Geronimo’s case forward.

AMY GOODMAN: And Johnnie Cochran, of course, who is known by everyone for representing O.J. Simpson, said it was this case that was his most important case, that he would not rest until Geronimo ji-Jaga was free. Why was this so important to Johnnie? He was his court-appointed attorney, is that right?

STUART HANLON: Right. Because Johnnie, you know, through all the fancy suits and ties and O.J., was ultimately a man who truly believed in justice. And I got to know him really well in this case. And Johnnie Cochran, as a DA — he was a DA for about four years under Van de Kamp — would always write parole letters for Geronimo on DA stationery and got in trouble. He believed Geronimo was innocent. And that meant so much to him. And he always said, and it was true, this case meant so much more to him than any other case. And one of the really amazing sights at Johnnie’s funeral, there were so many dignitaries and — “dignitary” is the wrong word, but so many well-known people — and everybody wanted to hear one person speak. And, you know, Johnnie, wherever he was, did, too. And that was Geronimo Pratt. And Geronimo was eloquent, and he was the key speaker at Johnnie’s funeral, because those two were joined at the hip, not only coming from Louisiana, but as African-American men and their search for justice from different directions. Johnnie, it was the happiest day I ever saw, all of us, when Geronimo walked out of prison.

AMY GOODMAN: And we’re going to go to that moment. Stuart Hanlon, thanks so much for being with us, and thank you to Ed Boyer for all of your work and for being with us this morning, retired Los Angeles Times reporter, as we turn now to that day, June 10th, 1997, amidst loud cheers from his family and supporters, former Black Panther Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt walking out of a Santa Monica, California, courtroom after a judge released him on $25,000 bail, just 12 days after reversing his 1972 murder conviction. This came within an audio report from KPFK in Los Angeles. This is Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt speaking upon his release.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: I just wanted to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your fair and courageous ruling and assure you that any further proceedings in this case, I will be the first one here, because I’ve been trying to resolve the merits of this case for all of these years, to find out who killed Mrs. Olsen, not any technicalities to try to put it off. And I am so happy that you’ve given me the chance to finally expose the truth about who killed Mrs. Olsen. And you can rest assured that I will adhere to every order and every instruction that this court indicates for me to follow. And that’s my word as a Vietnam vet and as a man.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, June 10th, 1997, when he was freed by a California judge after serving more than a quarter of a century in prison. He died at the age of 63 in Tanzania last Thursday.

Media Options