Guests

- Michael Ratnerpresident emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights and a lawyer to Julian Assange and WikiLeaks.

Attorney Michael Ratner responds to today’s verdict in the Bradley Manning trial. Manning was found guilty of 20 charges in total, including espionage, but he was acquitted of aiding the enemy, the most serious charge. “For him facing 136 years in jail for telling the American people what our government should have been telling us — about torture centers in Iraq, 20,000 extra civilians killed in Iraq — I find outrageous,” Ratner says. “He shouldn’t be put on trial. He is a whistleblower. The people that should be put on trial are the people who actually did those human rights violations.”

AMY GOODMAN: And we’re going to talk right now with Michael Ratner, Michael Ratner who is the president emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights and, particularly significant right now, the attorney for Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, both of which was raised repeatedly during this trial. He has been attending throughout the court-martial at Fort Meade, Maryland, of Bradley Manning, and he’s joining us now in New York in the studio.

So we’ve just gotten word that Bradley Manning has been acquitted of the most serious charge, aiding the enemy, but the number of charges that he was found guilty of could put him in jail for some 130 years. The sentencing portion of this court-martial will begin tomorrow morning at 9:30 Eastern time. Michael, what’s your response?

MICHAEL RATNER: I mean, Amy, he was charged with 22 different counts, from aiding the enemy to espionage to theft, essentially found guilty of 20 of those counts. So, in that sense, it’s a horrible, horrible thing that’s happened to him. I mean, to have him facing 130 years in jail for telling the American people what our government should have been telling us about torture centers in Iraq, about 20,000 extra civilians killed in Iraq, I find outrageous. He shouldn’t be put on trial. He’s a whistleblower. The people who should be put on trial are the people who actually did those human rights violations.

It is good, of course, that he was found not guilty of aiding the enemy, because that was the charge in which the government, which has overreached in this entire case, but was overreaching beyond belief, because that would have made anybody who published anything that al-Qaeda or any, quote, “enemy,” whoever they are, would read guilty of aiding the enemy, whether the whistleblower or the publisher. So we’re glad to be rid of that, but he should—Bradley Manning should have never been charged at all, in my view. Certainly, they should not have made whistleblowing into espionage. Five counts of espionage he was convicted on, each one carrying 10 years.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, on aiding the enemy, we keep referring to it and saying he was acquitted of it, but what does it actually mean? Why was he even being tried under this charge?

MICHAEL RATNER: You know, I can’t figure out what the government was trying to do. What it is, is if I’m, let’s say, a whistleblower, and I find some information about human rights violations or war crimes, and I pass them on to whether it’s Amy Goodman and Democracy Now! or The New York Times or WikiLeaks, which it was in this case, the government claims that by my passing it on to anyone that’s really reading the worldwide Internet—and that’s everybody, because that’s why the government said it’s worldwide—that anybody reading that, including our enemies, will then read it, and I’m going to be accused, as the whistleblower, of indirectly aiding the enemy through the means of WikiLeaks or Democracy Now! So that’s completely unheard of in my life as a lawyer who worked on these cases all of the time. I’ve never heard a case where you could simply put—give something to a publisher and then be accused of aiding the enemy. It normally was a crime that took intent. You had to actually intend to aid the enemy. The judge had ruled that out. In that sense, her ruling saying that you didn’t require intent is a bad ruling.

Her ruling, obviously, acquitting Bradley Manning of aiding the enemy is very important—very important for Bradley Manning, because it carried, as you said, a life sentence, if not the death penalty; very important obviously for future whistleblowing and journalists, who will hopefully not be charged with aiding the enemy; very important for all of us out there, from the news media like Democracy Now!, from WikiLeaks and others, who have said this charge is completely outrageous. You can’t do it.” But I just want to emphasize, it’s incredibly good that he was acquitted of that, but it’s incredibly bad that he was charged and convicted of 20 charges out of 22, carrying 133 years in jail.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Michael Ratner. He is president emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights. The ACLU has just put out a statement. Ben Wizner, director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy & Technology Project, said, quote, “While we’re relieved that Mr. Manning was acquitted of the most dangerous charge, the ACLU has long held the view that leaks to the press in the public interest should not be prosecuted under the Espionage Act. Since Manning already pleaded guilty to charges of leaking information—which carry significant punishment—it seems clear that the government was seeking to intimidate anyone who might consider revealing valuable information in the future.” Those are the words of the American Civil Liberties Union.

And Brad Manning’s family, written by his U.S.-based aunt, responded, as well. In summary, a portion, “While we’re obviously disappointed in today’s verdicts, we’re happy that Judge Lind agreed with us that Brad never intended to help America’s enemies in any way. Brad loves his country and was proud to wear its uniform.”

MICHAEL RATNER: I mean, the horrible part of this is really what they’ve said, that he’s facing this huge sentence for actually doing something and giving us information that we all should know.

AMY GOODMAN: So, again, he has been acquitted of aiding the enemy, but if you add up the charges and the years that he could face for the charges he was convicted of, he faces 136 years in prison.

MICHAEL RATNER: That’s correct, 136 years for a 25-year-old man who gave us incredibly important information.

AMY GOODMAN: What was some of that information, Michael?

MICHAEL RATNER: No, there was a major story that you actually carried part of on the Iraq torture centers in Iraq that were set up by the United States—General Petraeus knew about it—in which literally hundreds of people were taken to these torture centers every month, and they were tortured—set up by the United States. Has anybody ever been prosecuted for that? No. The story published by WikiLeaks that 20,000 more civilian deaths happened in Iraq than were known at the time—and that story was very important, because as a result of that story, the Iraq government refused to sign a status of forces agreement with the United States guaranteeing immunity to U.S. soldiers, because they said, “You’re not investigating your own soldiers. You’re not disciplining them. We’re not going to give them immunity for going out here and killing Iraqis.” That’s one of the big issues that forced—that forced U.S. soldiers out of Iraq. And, of course, the video you’ve shown that is just heartbreaking every time we’ve seen it, the “Collateral Murder” video, the murder of the two Reuters journalists by an Apache helicopter and the incredible bloodlust, as Bradley Manning described it, as those journalists were killed, as the people wanting to rescue or at least try and save the wounded on the ground were shot at, children injured, their parents killed.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re actually showing the video right now of the second part of that attack, first the attack on the journalists and the men who were taking them around this area, and then this van pulls up, a man with his children. He was taking them to school, stops to pick up the wounded. And they pick up the wounded, and then you see the Apache helicopter—this is the video from the Apache helicopter—opening fire on that van with wounded inside, the children critically wounded, the father killed. This is the video that WikiLeaks put out that they called “Collateral Murder.”

MICHAEL RATNER: That’s just some of it, and it’s heartbreaking. You think about this soldier who was 21 or 22 when he—22 when he probably saw that video. And he said to himself, “This has to get out.” They made a FOIA request. It’s not even a classified video. Why aren’t they putting it out?

AMY GOODMAN: And Reuters had actually asked for that information, for their employees—

MICHAEL RATNER: Asked for it.

AMY GOODMAN: —to see what happened to them in the last moments of their life, and weren’t able to get it. And Bradley Manning saw this and knew that.

MICHAEL RATNER: Saw that, saw that they made a FOIA request, Freedom of Information Act request, had been essentially told, “We can’t find any video here.” It was well known that it was there. There’s nothing classified in that video. It wasn’t even classified. Now I ask you—that’s something that the American people and the people of the world ought to know. And that’s the way you can begin to get some change in how our government fights its wars. But you hide that stuff; you keep it secret. I mean, if you look at Bradley Manning in another way, this is a person who basically told us about a secret government and secret wars and secret diplomacy that this country is running. And in some way, you can look at Bradley Manning as opening the door, along with WikiLeaks, to then later the revelations of Edward Snowden. I mean, what you can say is we’re really seeing a period where young activist people, young people who have a conscience and see these atrocities happening say, “This has got to stop. The American people have to start debating what our government is doing in secret.” These people are not the people who ought to be prosecuted. The people committing the war crimes ought to be prosecuted.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to go on with this broadcast for just another, oh, 10 minutes or so. We’ll end at 2:30 Eastern Standard Time. But, Michael, you are the attorney for Julian Assange and WikiLeaks. It was raised numerous times throughout this trial. Why? And what is the significance now that you’ve heard the verdicts in the case of Bradley Manning? Again, he was acquitted of the most serious charge, aiding the enemy, for which he could have faced life or even death, but the combination of charges of which he was convicted of espionage and theft-related charges could land him in jail for more than a hundred years, 136 max. What does this mean for Julian Assange, now holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy, where he was granted political asylum, but he can’t get out to go to Ecuador because the British authorities say they’ll arrest him if he does?

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, you know, this trial was a—yes, it was about Bradley Manning. It was about—and, obviously, we’re extremely disturbed over what’s happening to Bradley Manning. But it was also, when I went to those trials and heard Julian’s name dozens of times, WikiLeaks’ name dozens of times, essentially being accused of being in a conspiracy with Bradley Manning. What they said at the trial is Bradley Manning worked for Julian Assange, or he worked for WikiLeaks, he used their—the list of their—their wanted list to get the documents he did, he was taking direction from WikiLeaks—trying to put WikiLeaks and conspiracy with Bradley Manning. That’s still pretty clearly the government’s goal. It was the government’s goal two days ago, when I heard the summation. It remains the government’s goal today. It’s very likely there’s an indictment against Julian Assange for what the government claims is a conspiracy.

And when you look at that in the context of what the U.S. is doing to journalists, you understand that this is something extremely serious. You look at what happened to James Rosen, the Fox News analyst or Fox News reporter, whose records were subpoenaed because he was in touch with a whistleblower. And what they did is they subpoenaed James Rosen’s records. And what did the affidavit subpoenaing him say? It said he was a co-conspirator, or basically a conspirator in violating the espionage laws. This is a reporter. Likewise, James Risen, The New York Times reporter—

AMY GOODMAN: James Risen of The New York Times.

MICHAEL RATNER: Risen, New York Times, was working on a story from a whistleblower about Iran and its—and what’s going on with its nuclear program. What do they do when he tries to not testify at a trial against the whistleblower? The government appeals it and said—and gets a decision saying he has to testify who his source is. But worse than that, in the decision that’s written, it said this crime, this espionage crime by Sterling, who was the whistleblower, could not have been committed without James Risen. They’re saying, again, Risen co-conspirator, Rosen co-conspirator, WikiLeaks co-conspirator. What they’re doing is they’re trying to take journalists and put them into the—into their web, where they—it looks, for them, more legitimate to go after the journalists if they can call them co-conspirators. It’s not legitimate to go after the whistleblowers. It’s not legitimate to go after the journalists.

And what this verdict means, of course, five counts of espionage—and I want to say the espionage statute applies to journalists. It applies to anyone, actually. It applies to you or me holding WikiLeaks—holding Bradley Manning documents, WikiLeaks documents. It’s that broad of a statute. And it wouldn’t surprise me at all, while it’s never been used against journalists directly, and there seems to be some hesitation for doing it, they certainly want to try and push journalists into the—into the same place as the sources and then be able to prosecute them under the espionage statute.

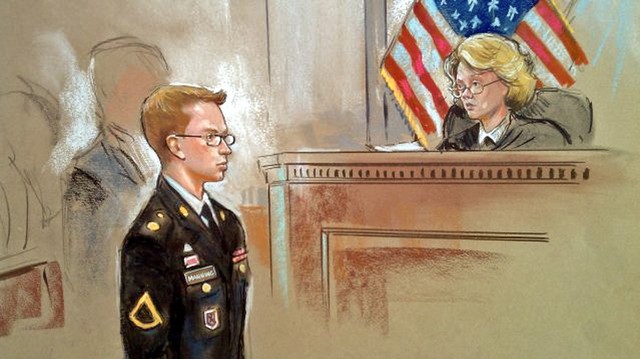

AMY GOODMAN: Judge Lind, Judge Denise Lind, the colonel who is the judge and jury, quite literally—first of all, explain why Bradley Manning felt it was better to have just a judge try—just a judge both try and decide this case than a jury. She is now moving on from her position.

MICHAEL RATNER: The lawyer for Bradley Manning, David Coombs, has never explained why he chose a judge rather than a jury. What we can suppose are, one, juries are not picked by lottery or from a pool. Juries are picked by the convening authority, which is the general in charge of that military tribunal, who actually picks who the jurors are going to be. So you’re not getting a jury that’s made up, by chance, of a random population. You’re getting one that the convening authority, who is actually the person who presses the charges against Bradley Manning, picks. So you’re—it’s not a guarantee of fairness.

Secondly, I think there was some concern expressed by somebody that was on Democracy Now! last week, saying perhaps the fact that he was—that he was—that he had issues around gender, and those were coming out, that that might have made a jury hostile to him. I think it’s more likely the first reason, that it’s essentially a hand-picked jury by the convening authority.

The judge, interestingly enough, has been promised or given an appointment to the next highest military court, the appeals court, which I find extraordinary, that in the middle of a trial of the most important whistleblower in United States history, that the judge who’s presiding at it be given a higher position. And, of course, this has—it brings us right back to Daniel Ellsberg. During Daniel Ellsberg’s trial for espionage, which eventually just collapsed under all the government chicanery, hypocrisy, etc., the trial judge in that case was actually offered to be the head of the FBI. Haldeman, from Nixon’s office, went out and sat on a park bench with him, overlooking the Pacific, and said, while the trial is going on, “Hey, Judge, how would you like to be head of the FBI?” I mean, you talk about influencing a judge by the executive. You’re seeing it both in the Ellsberg case, and now you see the other crucial, major whistleblower, the same thing happening, the judge being offered a higher position. I find it pretty remarkable that they would mess around and make it look like that judge may not have a complete fairness.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, I think we can be pretty sure that after the sentencing phase of the trial, that could go on for weeks, it will go right to the appeals court.

MICHAEL RATNER: Yes, that’s the other thing. It goes to the same appeals court where she’ll be sitting. Now, she won’t actually sit on the case. There’s probably a dozen judges or nine judges, and they pick three. But if you’re sitting there with your fellow judges and you’re having lunch with them every day out there, are they going to say, “Hey, Judge, you know, we’re about to reverse your decision. We’re about to tell you you really did bad.” You know, there’s a human dynamic here that’s at play on the same level, and it’s unlikely—it makes it less likely that we’ll get a reversal out of that court.