Guests

- Rev. James Lawsoncivil rights icon and Holman United Methodist Church pastor emeritus. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called him “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

- John Dearlongtime peace activist and the author of 30 books on peace and nonviolence, including The Nonviolent Life and Thomas Merton, Peacemaker. He is a lifelong anti-nuclear activist and has led peace vigils at Los Alamos for the last 12 years.

On the 70th anniversary of the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we are joined by peace activists from across the nation who are convening in Los Alamos, New Mexico, birthplace of the atomic bomb and home to the country’s main nuclear weapons laboratory and the site of ongoing nuclear development. This afternoon, activists will march toward the laboratory’s main entrance calling for nuclear disarmament. We speak with Rev. John Dear, author of “The Nonviolent Life” and “Thomas Merton, Peacemaker.” He helped organize this weekend’s Campaign Nonviolence National Conference to mark the 70th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. We’re also joined by the conference’s keynote speaker, Rev. James Lawson, civil rights icon and Holman United Methodist Church pastor emeritus. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called Lawson “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

Transcript

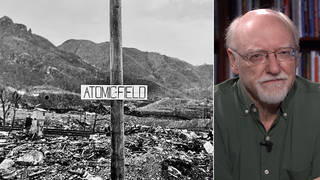

AMY GOODMAN: We turn from the target of the atomic bomb to its birthplace, on this 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Today, hundreds of peace activists from across the nation are convening in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the atomic bomb was built. Los Alamos is also the birthplace of the nation’s main nuclear weapons laboratory and the site of ongoing nuclear development. This afternoon, the peace activists will march up Trinity Drive toward the laboratory’s main entrance calling for nuclear disarmament.

For more, we go to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where we’re joined by two of the nation’s leading civil rights and peace activists. Reverend John Dear, author of over two dozen books on peace and nonviolence, including, most recently, The Nonviolent Life and Thomas Merton, Peacemaker, he has led peace vigils at Los Alamos for the last 12 years and helped organize this weekend’s Campaign Nonviolence National Conference to mark the 70th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. We’re also joined by the conference’s keynote speaker, the Reverend James Lawson, civil rights icon, Holman UMC pastor emeritus. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called Reverend Lawson, quote, “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Reverend Lawson, let’s begin with you. Can you tell us your memories of August 6, 1945? Where were you? How old were you?

REV. JAMES LAWSON: I was 17 years old. I was a junior in high school, getting ready to start my final year in Washington High School in Massillon, Ohio. I will never forget, because shortly after the bomb was dropped on the 6th of August, the National Forensic League changed its debate topic for schools across the country from whatever it was already designated to a new topic. And that topic went something like this: Does the atomic bomb make mass armies obsolete? Which meant, for us at Washington High School, an enormous amount of work of study, of research, of reading. So that was our debate topic from September until June of that ’45, ’46.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you—

REV. JAMES LAWSON: So this is all planted pretty indelibly in my ears.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you have any sense of the mass casualties? I remember the stories, hearing about the stories, especially at Los Alamos, of the footage that was classified, the video footage that the military took of the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, playing it for the scientists at Los Alamos. They described weeping, throwing up, and then that footage was put away for many years. Did you have a sense of the more than 200,000 Japanese who were killed 70 years ago today and on August 9?

REV. JAMES LAWSON: From the very beginning, there was, on the one side, the government’s attempt not to get full information available. So, from the very beginning, there was a conflict over how many people were actually killed, how many people were injured. From the very beginning, the issue of radiation of the GIs who moved in to occupy Hiroshima was controversial, and whether that radiation was dangerous. The pain and suffering of the entire city and it having been literally vanquished from the Earth, that issue was rarely talked about and was considered maybe classified, but our own government did not want to reveal the awesome character of the devastation.

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend John Dear, you are leading a series of actions beginning today in Los Alamos. Can you talk about your response to what took place 70 years ago and what you think needs to happen today?

REV. JOHN DEAR: Well, thank you, Amy. Yeah, we’re just continuing to try to build up the movement to call for the total abolition of nuclear weapons. And Los Alamos is the birthplace of the bomb, and business is booming, and so we’re going there to, in a spirit of nonviolence, invite the 20,000 employees who build the heart of every bomb, nuclear bomb, to quit their jobs and to call for the closing of Los Alamos.

As you know, two years ago, the United States Congress approved spending $1 trillion over the next three decades to upgrade our nuclear arsenal. This is insanity. And very few people are talking about it. Los Alamos has more millionaires per capita than any city in the country, the richest county in the country, sitting above the Santa Clara Pueblo, the second-poorest county in the country. You know, they continue to—they spend $2 billion a year building new bombs. President Obama is trying to upgrade the whole nuclear facility there, in effect building a state-of-the-art plutonium bomb factory.

What do you do? In solidarity with our people and our brothers and sisters in Japan, we’re going to march in silence, we’re going to sit in silence, we’re going to have a rally in the park on the physical spot where they actually built the Hiroshima bomb 70 years ago. We’ll do it again on Sunday with hundreds of people from across the country and, maybe most importantly, local New Mexicans. And we’re saying, you know, the place has to close, it’s a threat to the environment out here, it’s a waste of money, it’s not making us safe, and so forth and so on, trying to keep the movement alive and trying to build the movement. And meanwhile, we’re having the conference on nonviolence, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to Yuko Nakamura, a survivor of the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima. In 2007, [she] appeared on Democracy Now! and described what happened that day. At the time of the bombing, she was 13 years old.

YUKO NAKAMURA: [translated] We saw the big lightning, and I felt like that big blast is coming. And the blast is contaminated with glass and dust, and blew through the inside of our factory. And I was knocked down to the floor. All the little pieces of the glasses is stuck in my body. It’s all over my body, the whole entire body. And it got—my uniform got red and stained with blood, and I had a bloody nose and bleeding all over my body.

AMY GOODMAN: A Hiroshima survivor speaking with us, Yuko Nakamura, remembering the bombing of Hiroshima that she survived. The name given to the survivors is hibakusha, atomic bomb survivor. John Dear, for many years hibakusha would come to Los Alamos. I remember one year covering them as they spread seeds over the site where the bombs were built.

REV. JOHN DEAR: Yes, two years ago we hosted a delegation of 25 hibakusha and their children. Imagine, they had never left Hiroshima, and they got off the plane and came into New Mexico, up—and we took them up to Los Alamos. And they wept and told us their stories. But they were also very moved to find out that ordinary Americans are calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons with them. And so there was hope there, I thought, as we befriended each other and continue to build connections, especially from Los Alamos and Santa Fe, in New Mexico, with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And this is our hope. We continue to build global solidarity, a global movement to abolish these weapons once and for all, and take that trillion dollars to end poverty, clean up the environment and fund nonviolent conflict resolution.

AMY GOODMAN: In 2013, President Obama spoke in Berlin, Germany, and called for nuclear reductions.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Peace with justice means pursuing the security of a world without nuclear weapons, no matter how distant that dream may be. And so, as president, I’ve strengthened our efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, and reduced the number and role of America’s nuclear weapons. Because the New START Treaty, we’re on track to cut American- and Russian-deployed nuclear warheads to their lowest levels since the 1950s.

AMY GOODMAN: That was President Obama speaking in Berlin in 2013. Shortly afterwards, Fox News contributor Charles Krauthammer criticized Obama for discussing nuclear arms reduction.

CHARLES KRAUTHAMMER: The idea that we’re going to be any safer if we have a thousand rather than 1,500 warheads is absurd. So why is he doing this? Number one, he’s been obsessed with nuclear weapons and reducing them ever since he was a student at Columbia and thought that the freeze, which was the stupidest strategic idea of the '80s, wasn't enough of a reduction, and second, because I think that’s all he’s got.

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend James Lawson, your response?

REV. JOHN DEAR: His earpiece came off there.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Reverend John Dear, your response, as you just heard?

REV. JOHN DEAR: Well, yeah, you know, President Obama has said great things about the need to abolish nuclear weapons, but the practice is we continue to fund developing them and upgrading, at an enormous cost, where that money is needed for just basic human needs here in the United States. So, you know, this is the great problem we’re facing with our government right now. And the solution is, we need a new, stronger, grassroots movement in the United States, connected with the global movement, to say, “We need to start working for the abolition of nuclear weapons now.”

AMY GOODMAN: In this last—

REV. JOHN DEAR: We can’t wait. And we can’t have just one or two. We need to get rid of all of them.

AMY GOODMAN: In this last minute we have together, Reverend James Lawson, it’s also the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Voting Rights Act, August 6, 1965. The significance of what the Voting Rights Act means to all of these different issues?

REV. JAMES LAWSON: Well, the—making the democratic experiment from July 4th, 1776, in the United States accessible to all the citizens, to all the people, is a part of the major task that has to be continued within the United States. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, therefore, is one of the most important tools for that. It broke open, especially in the South, but also in places like New Mexico and California—it broke open the possibilities of people with a different language and of black people, especially, being allowed to vote, being able to vote without all the hatred and rage against their voting and their right to vote. They were acknowledged as citizens.

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend Lawson, we’re going to continue the discussion on the Voting Rights Act after the show and post it at democracynow.org. I want to thank Reverend James Lawson and Reverend John Dear.

That does it for our show. I’ll be speaking tonight in Manhasset on the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Check our website.

Media Options