Pandemics, like revolution, war and economic crises, are key determinants of historic change. We look at the history of epidemics, from Black Death to smallpox to COVID-19, and discuss how the coronavirus will reshape the world with leading medical historian Frank Snowden, author of “Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present.” He is a professor emeritus at Yale University who has been in Italy since the pandemic began, and himself survived a COVID-19 infection.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman. Forty-eight states are at least partially reopening this week, even as more than a dozen states are seeing an uptick in cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns the U.S. death toll will pass 100,000 by the beginning of June. Last week, ousted U.S. vaccine chief Rick Bright testified that if the U.S. fails to improve its response to the virus, COVID-19 could resurge after summer and lead to the “darkest winter in modern history.” Coronavirus hot spots Italy and United Kingdom are both also slowly reopening businesses.

This comes as the World Health Organization will meet virtually today with all 194 member states, and the global coronavirus death count passes 315,000 with more than 4.7 million confirmed infections. This is Dr. Mike Ryan, head of the World Health Organization’s Emergencies Programme, speaking at a recent briefing.

DR. MICHAEL RYAN: To put this on the table, this virus may become just another endemic virus in our communities. And this virus may never go away. HIV has not gone away, but we’ve come to terms with the virus.

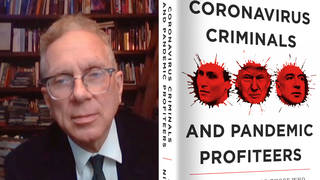

AMY GOODMAN: Well, as global leaders prepare to discuss what to expect in the months and years to come, we’re going to look back today at the history of pandemics and how they end, with the renowned historian Frank Snowden. He’s a professor emeritus of the history of medicine at Yale University and author of the new book, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. Professor Snowden is joining us from Rome, Italy, where he traveled for research before the coronavirus outbreak and has remained under quarantine since. He has recently recovered from COVID-19 himself. He also lived through a cholera outbreak in Rome while conducting research there almost half a century ago.

In his book, Professor Snowden writes, quote, “Epidemic diseases are not random events that afflict societies capriciously and without warning. On the contrary, every society produces its own specific vulnerabilities. To study them is to understand that society’s structure, its standard of living, and its political priorities.”

Professor Frank Snowden, it’s wonderful to have you with us, albeit from Rome, where you’re under lockdown. What an amazing history yourself, as you are an expert in pandemics. In Italy, you survived the cholera outbreak half a century ago, and now, though getting COVID-19, you have survived this coronavirus pandemic. Can you talk about those two experiences?

FRANK SNOWDEN: Oh, certainly. Thank you. I’m delighted to be with you.

And the cholera outbreak was in 1973. It’s one of the reasons that I was — I took up an interest in the field, because the sorts of events that I was witnessing as a young man were quite extraordinary. They included such things as — Naples was the epicenter. Rome was nonetheless affected, but Naples was the center. And cars with Naples license plates were being stoned in the center of Rome. And there are open-air markets in Rome, and the vendors there were having their stalls overturned, and they were being attacked by crowds as being guilty of spreading the disease.

At the same time, Italy, at this time, let’s remember, was the seventh industrial power in the world, in the 1970s. And the minister of health of this power went on television. And what he did was to say that the microbe that causes the cholera is exquisitely sensitive to acid, so all you need to do is to take a lemon and squeeze just a bit of it on your raw muscles, and then you’ll be perfectly safe. And, of course, if you believe that, you’re likely to believe just about anything. And so, it was this sort of event that caught my attention.

And later on, when I was studying something else entirely, there was a cholera outbreak in Italy, and I began thinking, in my studies, that actually this showed more conclusively what values were in Italy, in Italian society, what living standards were, and so on, than any other kind of work that I might do. And so I moved into studying the history of epidemic diseases, and I’ve been doing that alongside an interest in modern Italian history, those two things ever since. So, that’s the cholera story.

With the coronavirus story is that I finished a book, my book that you mentioned, kindly, in October. It was published then. And I had been quite concerned about the possibility of a major pandemic disease — not just myself, but many people were — and I wrote that in the book. And so, I was stunned, though. I didn’t know when it was likely to happen; I thought one day in the future. And so I was stunned that in December the epidemic started.

And then, by the time I came to Italy in January, it really began to ramp up. And very soon, I was living in the epicenter of the coronavirus at that time. So, that was a very important experience for me. I was not able to do the research I came to do, and I’ve devoted myself ever since to doing that. And I guess you might say that I had a little bit too much enthusiasm for my work and caught the disease myself — fortunately, a mild case, and I’m here to tell the tale, and so I was lucky in that regard. But I certainly have had a close look at this event, this series of events, in Italy, and I’ve been reading intensively about it and talking to people about it around the world.

AMY GOODMAN: And our condolences on the death of your sister just a few weeks ago.

FRANK SNOWDEN: Oh, aren’t you kind? Yes, that was not a result of coronavirus, but, yes, and I wasn’t able to go back. And that’s, you know, another part of the times we’re living in. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, your family history is so fascinating, your father the first African American envoy to Italy in the 1950s. He goes on to write Blacks in Antiquity and Before Color Prejudice. And your connection, all of these years, to studying Italy, until now — you are locked down there for months. Can you talk about the comparison of the lockdown there and what you’re viewing, your country here, the United States? You joked about — not really joked, but talked about lemon as a cure. Do you see comparisons to the president of the United States, President Trump, telling people to inject themselves with disinfectants?

FRANK SNOWDEN: I’m glad you asked that question. And I would say that what I’ve observed here, I’ve heard a lot of discussion across — in the States, about Italy’s terrible response to the coronavirus. And I find that surprising, because it seems to me quite the opposite.

First thing has to do with compliance. And there, I think a lot has to do with the messaging. That is to say that in this country, you have a single health authority, and it acted — it acted quickly and responsibly, and it imposed social distancing. And as it did so, there wasn’t a cacophony of noise from a president speaking differently from his advisers, differently from the governments of 50 states, from local school boards, local mayors, different members of Congress. No, there was one policy. It was announced. It was explained very clearly to the population that until we have a vaccine, that we have exactly one weapon to deal with this emergency, and that’s social distancing. And therefore, if we — Italians were told, if we Italians want to save our country, we have to do it together. We’re all in the same boat. This is the only means available to save the country, to save our families, to protect our communities, to protect ourselves.

And as a result, there’s been — and I’ve observed this even in the neighborhood where I’m living, that the compliance has been extraordinary. There haven’t been protests against it as in the States. And I would say that it’s interesting that the local newspaper — it’s called Il Messaggero, which means “The Messenger” — had an article in which it said this is the first time in 3,000 years of Rome’s history that the population of Romans has ever been obedient. And I think that’s because people were — the government was very clear. Vans went through the neighborhoods. There were posters everywhere. The regulations were explained to everyone. They were very severe, more severe than in the States. But people were justifiably afraid. The government explained why this was a danger, and people were afraid, and they wanted to do something.

I myself heard the kinds of conversations that people had when they were waiting outside grocery stores, were wearing their masks, and they were conversing with each other and saying things like “I wonder if this was like the way it was during World War II. Is this maybe the way it was during the Blitz in London, that everyone is in this together, it’s a terrible sacrifice, but this is what we have to do?” This was the attitude that I observed.

And now that I’m able to go outside again the last few days, I’ve observed on the streets again that this compliance is continuing. People have been well educated in the dangers of the coronavirus. And quite frankly, no one wants it to surge up again. I would say that’s the basis of it.

The opposite is happening and has happened in the United States, where we had, as I said, this cacophony of fragmented authorities all saying different things in an extraordinarily confusing way, and our great CDC, the world sort of model, the gold standard for emergency response, being underfunded and almost invisible throughout this crisis. So, it’s been staggering, a country that has extraordinary medical centers, has this extraordinary CDC, wonderful doctors, an extraordinary tradition of scientific research in universities, national labs like the NIH, and yet — and yet, when this virus approaches, it has been unable to respond — unwilling to respond, in a scientific, coherent way with a single message to the American public. And so the public is confused.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have the president also defunding the World Health Organization, an organization you have studied for years. You quote Bruce Aylward of the World Health Organization upon his return from China. Can you tell us what he said, Professor Snowden?

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes. He said that the world — China has had a model response, and the world will soon realize that it owes China a debt of gratitude for the long window of opportunity it provided by delaying the further onset of this virus, which gave the world a chance to prepare to meet it. That’s essentially what he said on return.

AMY GOODMAN: Did he also talk about people having to change their hearts and minds to deal with this global catastrophe?

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes. That was the second thing he said, that he said we must be prepared. And people said, “Well, how do we prepare?” And he said, “The first thing that happens is that we need to change our hearts and minds, because that’s the premise for everything else that we need to do.”

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Frank Snowden, you have long studied epidemics, and I was wondering if, in the brief time we have together, though we do have the whole show — if you can go back in time to the bubonic plague and very briefly talk about the Black Death, caused by a bacteria, then move on to smallpox, how it wiped out Indigenous people, from Haiti to the United States, and its connection to — this caused by a virus — its connection to colonization, to colonialism. Start with the Black Death.

FRANK SNOWDEN: Oh, absolutely. The Black Death reached Western Europe in 1347. It broke out first in the city of Messina in Sicily and spread through the whole continent. And it lasted until, in Western Europe — the story to the east is rather different, but in Western Europe, the last case was once again in Messina in 1734. So, that makes, unless I have my math wrong, 400 years in which it ravaged Europe and killed extraordinary numbers of people.

Now, this is a disease that’s spread by fleas, also by — and they’re carried by rats. It also can be spread through the air in a pulmonary form. And it’s extraordinarily lethal. It’s something like 50% of those who get the disease from being bitten by fleas perish. Nowadays we have antibiotics, but at the time of the Black Death, we didn’t, of course, and so 50% of those afflicted died. And the pneumonic version of the disease is 100% lethal. Even today, it’s almost 100% lethal.

And so, this is an extraordinarily dangerous disease. Its symptoms are also extremely powerful, painful and dehumanizing, and patients die in agony. And this can — it strikes very quickly, and so people can also be struck down in public. And so this becomes a terrifying public spectacle as people collapse in the streets. So, this —

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Snowden, the people suffered from what? Buboes, these massive inflammations of the lymph nodes?

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes. That’s as the disease spreads from the flea bite to the lymph node. There’s a massive inflammation, and you have a swelling, let us say, in your thigh or under your armpit or in your neck, that’s maybe the size of an orange, a large navel orange, under your skin. And it was said to be so painful that people even jumped into the — in London, into the Thames, into the Arno in Florence, to escape from the agony of this terrible pain they were suffering.

But there were other symptoms, as well: terrible fevers and also hallucinations, as people — it has neurological effects. That’s part of the dehumanizing side of it. There are these skin discolorations. There are many symptoms, and it’s an entirely dreadful and horrible disease.

It still exists, by the way. There are people who think that it’s just a medieval disease. No, there are something like 3,000 people around the world who die of bubonic plague every year, and some — a trickle in the United States, in the Southwest in particular, where there is a reservoir of it. So, it’s still there.

AMY GOODMAN: You knew a woman in Arizona who had bubonic plague?

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes, I knew someone in Arizona who got the bubonic plague, because they’re a disease — endemic disease of prairie dogs in the Southwest of the United States. And if pet dogs are taken out into areas where the prairie dogs live, they can have an exchange of fleas, and the fleas can be brought back to a hotel or motel. And that’s what happened to my friend. There were contaminated fleas in the room where she slept, and therefore she became a — she survived but was a victim of bubonic plague in the 21st century. So, we could be —

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Snowden, you talk about the bubonic plague, the responses to it, being quarantined, the sanitary cordons, mass surveillance and other forms of state power. And I also want to follow that through with these pandemics, is you have — you also are a scholar of fascism and the direction countries can go when such a crisis happens.

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes. Well, one of the things, I think, if a 15th century Florentine were to come back in a time machine today to look at what we as a society are doing, he or she would find it a rather familiar landscape. That is to say, the things that you’re saying were adopted and devised as self-protection by the Italian city-states that were at the center of the trade in the Mediterranean, and so were repeatedly scourged.

So, yes, there was this terrible disease, and they dealt with it by creating health magistrates — we call them boards of health — by creating the first forms of personal protective equipment, PPE, the masks, the long gowns, social distancing, hospital systems for dealing with this one single disease, the measure of quarantine — “quarantine” even being an Italian word, ”quaranta,” for 40 days, because people were locked down for 40 days before they were released. It had sanitary cordons. All of this was part of the defensive measures that we see today and that were also present during the Spanish influenza.

Public health was a legacy of the bubonic plague. So, while we look at these terrible events, we also need to remember that human beings are inventive and that there have been silver linings. The development of public health, the development of science and scientific medicine are also gifts of these terrible events. And indeed, I would say that the modern state is also part of — it was molded in part by the need for a centralized authority as part of our life protective system. So, yes, the bubonic plague does that, and it affected every area of society.

It’s not true to say that pandemics all do the same things. There are some things that have been repeated again and again. During the bubonic plague, the Black Death, the first years of it, there was this horrible surge of anti-Semitism across Europe, in France, in the Rhineland, in northern Italy, elsewhere. And this was, in a way, the first Holocaust, when Jews were persecuted and put to death, not just in spontaneous ways by crowds, but the bureaucratic apparatuses of political authorities were used to torture Jews into submission, to confessing crimes that of course they had never committed, and then they were judged and burned. The Holy Roman Empire did this, and local authorities and leaders of city-states. So this was a systematic purging and killing of Jews, who were thought to have — or so the case against them was that they were trying to put an end to Christendom and were poisoning the wells of Christians. And so, you have Jews tortured, broken on the wheel, burned alive, run through by the sword, and so on.

So, this xenophobia is — this blame, scapegoating, we see that today with the coronavirus. It’s something that can happen, has repeatedly happened, with the idea that this is a Chinese disease. It’s a foreign disease, we’re told, and therefore shutting borders against “Chinamen.” And we see that Chinese Americans, children being attacked in schools, Chinese Americans afraid to ride alone on the New York subway and arranging to travel in groups so they won’t do that. This is part of a long-term legacy of these diseases. And we see it in Europe, as well. Chinatowns were deserted long before the coronavirus actually arrived. And the right-wing nationalist politicians of Europe have been using that, saying it’s been imported by immigrants. So, that’s one of the false stories that’s followed in the wake of this. So that’s another really terrible recurring feature of these pandemic diseases.

They don’t always lead to — you were asking about does this always increase state power. Well, certainly, the Black Death in Eastern Europe, there were authoritarian countries, and they used these draconian, violent measures. Yes, it was part of their assertion of power. Indeed, this is one reason that these draconian measures appealed, because rulers, not knowing what to do, this gave the impression that they did: They knew what they were doing, and they were taking decisive measures. And so, it was thought that these sorts of measures would possibly be effective, and would certainly be a display of power and resolution. So, we do see that happening.

But let’s take the Spanish influenza of 1918, when, again, it’s a good comparison to today, because it was the time — it’s a respiratory disease. It was terribly much more contagious than this and deadly. Something like 100 million people are thought to have died around the world as a result of the Spanish influenza. And people practiced social distancing. Assemblies were banned. The wearing of masks was compulsory. Spitting in public, which was very popular at the time, was forbidden, and there were heavy fines in places like New York City for doing so. But it doesn’t result — measures were taken, but they were revoked at the end of the emergency, and one doesn’t find this leading, as it may in some countries, to a long-term reassertion of draconian power by political authorities.

With COVID-19, I think the message is mixed. And remember, anything anyone says about it, we have to remember that this is very early in this pandemic, and so we’ll have to wait and see what the final results will be. But we know already that Hungary and Poland have witnessed rulers who use COVID-19 as a cover for ulterior motives of becoming prime minister for life, with the capacity to rule by decree, to censor and shut down the press, to put their political enemies under arrest and so on. And those aren’t public health measures. So, I would say, yes, it has this potential, but it’s not necessarily something that we’ll see around the globe, although there is that danger, and we’ve seen those two countries where it clearly is leading to exactly those results.

AMY GOODMAN: Frank Snowden, we have to break. Then we’re going to come back, and I want to ask you about smallpox, about Haiti, the island of Hispaniola, and about Native Americans. Frank Snowden, professor emeritus of history of medicine at Yale University, author of the new book, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. He is speaking to us from the lockdown in Rome, Italy. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” performed by Marcella Bella. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. We’re spending the hour with professor Frank Snowden, professor emeritus of history of medicine at Yale University, author of the book Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. He has devoted his life to looking at epidemics and teaching thousands of students. He is now in Rome, Italy, where he has been for months, coincidentally went there for another project but got caught in the lockdown, got COVID-19, has recovered from that, and we are lucky enough to have him as our guest for the hour.

Professor Snowden, take us to Hispaniola in 1492, a different version of history that we learn about Hernán Cortés and Pizarro, from the Incas in Peru to the Aztecs of Mexico, what happened in Haiti and in the United States when it came to smallpox.

FRANK SNOWDEN: Yes. Well, Columbus landed at Hispaniola, the first place. His idea — the Arawaks were the Native population, and there were a couple of million inhabiting the island when he arrived. His idea was that he would be able to reduce them to slavery. He wrote about how friendly the Arawaks were and how welcoming to him, his ships and his men. But I’m afraid that the hospitality wasn’t reciprocal. And Columbus’s view was this was a money-making expedition, and here it would be wonderful to have the Native population as mines in slaves, and mines to cultivate the fields.

The problem was that there was a differential mortality. This has come to be called the Columbian exchange. That is to say that Native populations in the New World didn’t have the same history of exposure to various diseases, and therefore not the same herd immunity to them. The most dramatic example is smallpox. Measles was another. That is to say that Native Americans had never experienced those diseases. Columbus and his men, on the other hand, had, because it was rife in Europe. And so, unintentionally, for the most part, the Arawaks simply died off as they were exposed to these new diseases, smallpox and measles, and by 15, 20 years later, there were just a couple thousand left.

And it was at this time that in Hispaniola there was the beginning — this is one of the reasons for the beginning of the African slave trade. The Native population of the United States died from these diseases, and so the Europeans turned instead to importing people from Africa, because they shared many of the same bacterial histories, and therefore immunities, and could survive being enslaved in the Caribbean and then in the New World, on North America and also in South America. So, we get the beginning of the slave trade in part as a result to this differential immunity.

This, then, on the wider scale of the New World, this was something that was — devastated the Native population. When the Spaniards, the British, the French came, the Native population contracted their diseases and just was destroyed. This destroyed the Inca and Aztec empires. In fact, they were so devastated, that they lost their religion. They thought the white man had much more powerful gods than they did, and so this drove the missionary and conversion experience, as well, and cleared the land for European settlers across the whole of the continent. This was a tremendous impact of smallpox disease. It’s called a virgin soil disease because they were so — the population had never experienced it and had no herd immunity.

There’s an irony that we can see. Let’s go back to Hispaniola, that is now the island divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. And let’s talk about Haiti. It was Saint-Domingue at the time, by the 18th century certainly. And let’s remember that the French — this is now an island that had become, extraordinarily enough to think, the wealthiest colony in the world, the jewel of the French Empire. And that is because of its sugar plantations. And the sugar was exported to Europe and was the foundation of French wealth in this period. And slaves are continuing to be imported throughout the 18th century at breakneck speed to cultivate the fields of sugarcane.

During the French Revolution, French power was neutralized. The attitude of the French revolutionaries toward slavery was entirely different. And you got this upsurge of the slaves with the greatest slave revolt in history, led by the Haitian Spartacus, Toussaint Louverture. And the colony was functionally operating under Toussaint Louverture’s control and was independent of France. Napoleon — there was regime change, however, by 1799, and Napoleon comes to power. And by 1803, he’s thinking that he wishes to put an end to this rebellion, to restore the Haitian rebels, to reenslave them and to restore the colony to being this economic warehouse for France. So he sends a tremendous armada, led by a general who was married to his sister Pauline. And it was something like 60,000 troops and sailors who were sent to the former Hispaniola, now Saint-Domingue, to crush the revolt.

Once again, we see a difference in immunity to disease that proved decisive. That is to say that yellow fever was something to which the African slaves had a differential immunity, whereas Europeans had no immunity. They had no history of experience with yellow fever. And so, what happens is that the French soldiers in Saint-Domingue begin to die at a rapid rate of a terrible epidemic of yellow fever that sweeps through the Caribbean and especially through Saint-Domingue. And what happens, by — Toussaint Louverture was very aware of this and took advantage of it, luring the French troops, not fighting them in pitched battles but only small guerrilla campaigns, waiting for the summer months to come, and an upsurge of the disease, which happens. And pretty soon the French commander writes to Paris to say —

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Snowden, I’m only interrupting because we only have a minute. Of course, Haiti becomes the first country born of a slave rebellion, as you are so graphically describing with an alternative view of history, that many may not have understood, with the role of disease. But in this last minute we have, I wanted to ask you about how pandemics end and what you think will happen now.

FRANK SNOWDEN: I think there’s not one answer to that. Pandemics are all different, and they end in different ways. Some die out because of sanitary measures that people take against them, so that we’re not vulnerable in the industrial world to cholera or typhoid fever, that are spread through the oral-fecal group, because we have sewers and clean, safe drinking water. And other diseases end, like smallpox, because of vaccination, the development of a scientific tool. So it really depends. Some diseases are not very good candidates for vaccines.

And I would say that COVID-19, I’m sure that we will develop a vaccine, but I also fear that it may not be the — it won’t be the magic bullet that people believe, that it will put this behind us, because the sort of features you want are, for an ideal candidate, like smallpox, a vaccine that doesn’t have an animal reservoir so it can’t return to us. A vaccine is an ideal candidate if in nature it produces a robust immunity in the human body, so people, having once had it, are totally immune for life. That doesn’t seem to be the case with COVID-19. So I expect it to become long-term with us. We’re going to have to learn to live with this disease. It’s probably going to become an endemic disease, and so we’re going to have to adjust to —

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there. And I want to thank you so much, Professor Frank Snowden, professor emeritus of history of medicine at Yale University, author of the new book, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. I’m Amy Goodman. Stay safe.

Media Options