By Amy Goodman & Denis Moynihan

Two consecutive federal holidays – Juneteenth and Independence Day – highlight the sweep of American history, marking the birth of the nation on July 4th and, on June 19th, the liberation of the last group of enslaved people in the US, at the end of a devastating civil war.

Independence Day commemorates the day in 1776 when the text of the Declaration of Independence was agreed upon by the Continental Congress. Juneteenth is a compression of “June Nineteenth,” the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Texas were finally freed with the arrival of the Union Army in Galveston, two months after the end of the Civil War and over two years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

While these two holidays are celebratory, they afford an opportunity to reflect upon and hopefully to address this nation’s crimes and contradictions.

Take, for example, the most iconic statue in the United States, the Statue of Liberty. Formally named “Liberty Enlightening the World,” the statue was a gift from France to the United States. The idea of the statue dates back to 1865.

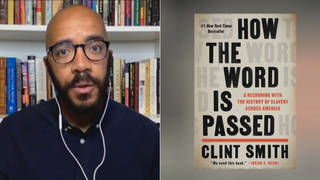

“Originally conceived by Édouard de Laboulaye, a French abolitionist…the idea of the Statue of Liberty and giving it to the United States as a gift was…to celebrate the end of the Civil War and to celebrate abolition,” Clint Smith, author of “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America,” explained on the Democracy Now! news hour.

He went on to describe a little-known feature of the statue–her shackles:

“The original conception of the statue actually had Lady Liberty breaking shackles, a pair of broken shackles on her wrists, to symbolize the end of slavery…they replaced the shackles with a tablet and the torch, and then put the shackles very subtly underneath her robe, but the only way you can see them, these broken chains, these broken links, is from a helicopter or an airplane.”

The statue sits atop a massive pedestal, blocking the view of Lady Liberty’s feet to pedestrians below.

The statue was to be unveiled in 1876 for the US centennial, but construction was delayed. By the October 28, 1886 unveiling, much had changed from when de Laboulaye conceived of the statue in 1865. Yes, slavery had ended, but so had Reconstruction, the rebuilding of the war-torn South intended to empower the newly freed Black population. Instead, the system of segregation and racist terror that would become known as Jim Crow was being instituted.

Meanwhile, women were still excluded from most aspects of economic and political life. The New York City Woman Suffrage Association rented a steamer to protest Lady Liberty’s unveiling, calling the use of the female form, in a country where they had no political rights, “a gigantic lie, a travesty and a mockery.”

Their protest disrupted the unveiling, including a keynote address by politician and businessman Chauncey Depew. His speech promoted democratic ideals but also denounced “anarchists and bombs” and declared “those who come to disturb our peace and dethrone our laws are aliens and enemies forever.”

The statue’s unveiling occurred just over five months after the “Haymarket Incident” in Chicago, when a rally for the eight-hour workday was disrupted by a bomb. The blast and subsequent police gunfire killed seven police officers and at least four civilians, injuring many more. Several key Chicago labor movement leaders were tried and executed following the massacre, ushering in an era of violence against labor organizing that would last decades.

The history of social progress in the United States is complex, interwoven and often bloody.

“If we don’t fully understand and account for this history, that actually wasn’t that long ago, that in the scope of human history was only just yesterday, then we won’t fully understand our contemporary landscape of inequality today,” Clint Smith said. “We won’t understand how slavery shaped the political, economic and social infrastructure of this country.”

It was Emma Lazarus’ poem “New Colossus,” commissioned by Joseph Pulitzer to raise funds for the statue’s pedestal, that forever linked Lady Liberty to immigration, with the line, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” For many of the 12 million immigrants arriving at Ellis Island from 1892 to 1954, the statue was their first sight of their new home.

Now, in 2024, the state of Texas, the first state to institute Juneteenth as a holiday, has deployed its National Guard and other armed agents to deter and deport asylum seekers at the US/Mexico border. And President Biden has joined the anti-immigrant fervor, shutting down the border to asylum seekers.

If Lady Liberty, torch in hand and broken shackles at her feet, could shed tears, she’d be doing so now. Tears of sorrow, yes, but also tears of joy for the movements fighting for liberty, enlightening the world.

Media Options