Guests

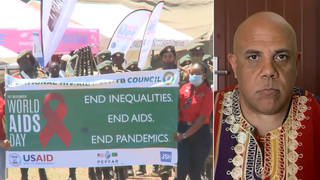

- Daniel García-PeñaColombian ambassador to the United States who was just recalled to Bogotá.

Tensions are escalating between Colombia and the United States as President Trump conducts deadly airstrikes on supposed “drug boats” in the Caribbean. Colombian President Gustavo Petro accused the U.S. of committing murder for killing a Colombian fisherman in one attack in mid-September and just recalled the country’s ambassador, Daniel García-Peña.

“Even if they were in fact carrying drugs, the procedure is to capture them, to seize them, to arrest them and to find information about who was behind them, and not blowing them up,” García-Peña tells Democracy Now! from Bogotá.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

A group of United Nations experts say U.S. strikes targeting boats in the Caribbean off the coast of Venezuela amount to extrajudicial execution. In recent weeks, the U.S. has struck seven boats, claiming they were being used to traffic drugs, but the U.S. has offered no proof to back up its claim. The U.N. experts said, quote, “These moves are an extremely dangerous escalation with grave implications for peace and security in the Caribbean region,” unquote.

This comes as President Trump has authorized the CIA to carry out lethal covert operations inside Venezuela. The CIA has also reportedly played a central role in the boat attacks, as well.

Tensions are also escalating between the U.S. and Colombia after the Colombian President Gustavo Petro accused the U.S. of committing murder for killing a Colombian fisherman in one attack in mid-September. President Trump responded by calling Petro a “lunatic” and a, quote, “illegal drug leader,” unquote. Trump also threatened to cut off foreign aid to Colombia and raise tariffs on Colombian goods. Petro then responded by writing, “Trying to promote peace in Colombia is not being drug trafficker,” unquote. This is Petro speaking Tuesday.

PRESIDENT GUSTAVO PETRO: [translated] I am making no mistake by speaking to the world from Colombia, because what I am demonstrating is that Colombia is the heart of the world. An aggression against Colombia is aggression against the heart of the world. I call on the world to help us. Before, I called on the world to help Palestine, now us, because they want to attack us, and they are mafia members, and Trump is believing them.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined right now by three guests.

Guillaume Long is former minister of foreign affairs for Ecuador. He’s a senior research fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Earlier this year, he wrote a piece in The Nation headlined “The Trump Administration Unabashedly Embraces the Monroe Doctrine.” He’ll talk about an Ecuadorian survivor of one of the bombings.

We’re also joined by Manuel Rozental, a Colombian physician and activist with more than 40 years of involvement in grassroots political organizing with youth, Indigenous communities and urban and rural social movements. He’s been exiled several times for his political activities. Manuel is part of the group Pueblos en Camino, or People on the Path.

But we begin with Daniel García-Peña, Colombia’s ambassador to the United States, who was just recalled to Bogotá as tensions rise with the U.S. He previously served as Colombia’s high commissioner for peace from 1995 to ’98. García-Peña also taught political science at the National University in Bogotá, Colombia.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! Ambassador, let’s begin with you. Why don’t you lay out why President Petro has recalled you from the United States?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: First of all, good morning, and it’s great to be here with you all.

No, it has to do with the statements on the part of President Trump this weekend that, first of all, accused President Petro of being the head of a drug cartel, threatened that if Colombia did not stop the flow of cocaine, that he would do it himself — statements that are completely unacceptable. And President Petro recalled me because that’s a mechanism that exists in diplomacy when situations like this arise, so that I can sit with the president, as I have done in these days with him, to analyze what is happening in Washington and how we can navigate these turbulent waters, because, well, first of all, these statements on the part of President Trump are simply unacceptable, but, secondly, they ignore the fact that there is no country in the world — and I say that unequivocally — in the world, that has done more to fight drugs than Colombia under the leadership of President Petro. So, that is why I’m here in Bogotá. And we’ll continue to seek ways that we can send that message to Washington so that these kinds of false statements can be corrected.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ambassador García-Peña, Colombia has long been one of the major recipients of foreign aid from the United States, and the United States is its main trading partner. What do you think is behind this, this now Trump administration hostility towards your country?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Well, it’s hard to know for sure or to speculate, but I think that, without a doubt, it has to do with these latest actions on the part of the Trump administration to use the military force in its supposed attempts to fight drugs, the bombing of these boats that are supposedly transporting cocaine, that violate international law, that is completely counterproductive, because if you were able to identify a boat that’s supposedly transporting cocaine, what we will do, and we have done, and we continue doing that on a daily basis with the United States, is to intercept it, to, first of all, verify that if — that they are truly smuggling drugs, and to capture those that are on those boats to see if you can get information about who the higher-ups are, because the people that are on those boats are not the drug traffickers, they’re employees of the drug traffickers. And so, it is completely ineffective to simply bomb them.

So, we have been very adamant, and President Petro has stood up to say that these are violations of international law and that they go against the logic of how law enforcement should deal with these situations. So, it appears that the position of our president, of President Petro, to call out the United States on these actions, I think that is part of the reason why President Trump is upset.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you comment on how U.S. policy has changed toward Latin America, especially with Secretary of State Marco Rubio being so much in charge of what — of U.S. policy in that region?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: Yes, well, without a doubt, there’s the — the new administration and Secretary Rubio has identified Latin America as a key area for what they call the “America First” policy. And it has been seen in several ways. First of all, the issue of immigration and how they are dealing with the flows of, the presence of what are called illegal immigrants in the United States, it is now seen with this new emphasis on the use of the military in the “war on drugs.” We’re also seeing it not only with Latin America and Colombia, but with the world, with the threats of the tariffs on the trade issue. So, it’s been in many fronts in which the policies of this administration mark a great difference from previous administrations — in fact, even from the first Trump administration, where some of these things did appear, but not with the emphasis and not with the intensity that we’re seeing now.

AMY GOODMAN: I can see a lot of people are trying to reach you, but I’m glad we are able to speak to you. You have — I mean, in the last days, I’ve been listening to a lot of officers, former officers, with the CIA saying, if they are using CIA intelligence, this is not evidence. Trump has admitted to both the CIA covert actions in Venezuela, but also that the CIA is being used in tracking boats. I also — you also have people like the Republican Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, who is raising a red flag, saying these are straightforward extrajudicial killings.

And I wanted to ask you about Alejandro Carranza. He’s the fisherman whose “loved ones say he left home on Colombia’s Caribbean coast to fish in open waters. Days later” — and I’m reading from CBS — “he was dead — one of at least 32 alleged drug traffickers killed in U.S. military strikes. From Santa Marta, northern Colombia, Carranza’s family is questioning White House claims that he was carrying narcotics aboard a small vessel that was targeted last month.” Can you tell us about Carranza and what exactly this attack was, and then the next one, this submersible, that killed two people, and there are two survivors that were repatriated to Ecuador and to Colombia?

DANIEL GARCÍA-PEÑA: You know, that’s a great question, because it indicates how, when you blow the boats up with the evidence or to find out exactly what was on the boat or what they were doing, well, it disappears along with the boat in the middle of the ocean. So, what we have been demanding is information as to — and then, not only Colombia. Senator Rand Paul is right on the money to demand from the administration these kinds of explanations, because even if they were in fact carrying drugs, the procedure is to capture them, to seize them, to arrest them and to find information about who was behind them, and not blowing them up. So, what we are seeing here is something that is really going beyond what has been the normal procedure and what international law establishes.

But the case of the two, of the Colombian and the Ecuadorian that were repatriated, is very indicative of the fact that there’s a lot of great legal doubt about how these operations can actually be carried out. The Colombian and the Ecuadorian that were — that survived the attack were on a Navy ship, and they really were in a quandary. They had no — they didn’t know what to do with them, because even though the Trump administration claimed that this is an act of war and that they should be treated as enemy combatants, there’s absolutely no substance to that claim. And so, they were — had to be repatriated, because they were simply unable to find legal way of maintaining them, or as enemy combatants, as they originally said, or just as drug traffickers, if they were accused, but there was no legal basis for this.

So, that’s, I think, a clear indication of how there are questions, very severe questions, about what is happening. There’s a speculation — I don’t want to go into them, but there’s a speculation about the resignation of Admiral Holsey, the head of SOUTHCOM. And this was all in the U.S. media, that supposedly his withdrawal also has to do with how the U.S. military and the U.S. Navy also have questions about the legality of all of this. So, I think that the matter of it goes beyond simply a situation specific of these individuals that were — that you mentioned. It’s a broader question about how the use of force, the elimination of these boats, of these people, that are supposedly carrying drugs, is really walking a very fine line between what is legal by international standards, but also by U.S. standards.

AMY GOODMAN: We also want to ask you about what’s happened with Uribe, the appeals court overturning the conviction of the former Colombian president. But we’re going to go to break, and in addition to Ambassador Daniel García-Peña, who is now speaking to us from Bogotá because President Petro has recalled him to Colombia from the United States, because of President Trump bombing boats in the Caribbean, we are also going to be joined by Guillermo Long — Guillaume Long, who is a former minister of foreign affairs for Ecuador, and we’ll be joined, as well, by Dr. Manuel Rozental, Colombian physician and activist. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “If You’re Coming for Me” by MAKU Soundsystem, performing in our Democracy Now! studio.

Media Options