As President Trump threatens to use U.S. special forces against drug cartels abroad, a new book, The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces, reveals some of the most secretive and elite special forces in the Army are heavily involved in narcotrafficking themselves. “There’s at least 14 cases that I’m tracking of Fort Bragg-trained soldiers who have been either arrested, apprehended or killed in the course of trafficking drugs in the last five years or so,” says author Seth Harp. The book also looks at “how U.S. military intervention often stimulates drug production,” including in Afghanistan, which he says became the biggest narco-state in the world during the 20-year U.S. occupation. “Most of the drug trafficking and drug production was being carried out and done by warlords, police chiefs, militia commanders, who were on the U.S. payroll in a corrupt structure,” says Harp.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

As the National Guard expands its presence in Washington, D.C., President Trump says he’ll seek long-term federal takeover of the D.C. police force.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: We’re going to need a crime bill that we’re going to be putting in, and it’s going to pertain initially to D.C. It’s almost — we’re going to use it as a very positive example. And we’re going to be asking for extensions on that, long-term extensions, because you can’t have 30 days. Thirty days is — that’s — by the time you do it — we’re going to have this in good shape.

AMY GOODMAN: Earlier this week, Trump declared a crime emergency in D.C., even though violent crime in the city is at a 30-year low. Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser has denounced Trump’s takeover of the police force as an “authoritarian push.” At least 800 National Guard troops are being deployed in D.C., alongside 500 federal law enforcement agents.

The Washington Post revealed Tuesday the Trump administration is also planning a so-called Domestic Civil Disturbance Quick Reaction Force composed of hundreds of National Guard troops set to rapidly deploy to other U.S. cities targeted by Trump, including Democratic strongholds of Baltimore, New York, Chicago, Oakland. The force would be comprised of two groups of 300 soldiers permanently assigned to the force, stationed at military bases in Alabama and Arizona.

This comes after Trump earlier deployed the National Guard and U.S. Marines to Los Angeles during protests against immigration raids and arrests by masked, unidentified agents who also targeted U.S. citizens when they were making their arrests.

Rolling Stone reports, quote, “One of Trump’s biggest regrets from his first term in the Oval Office, according to former and current senior Trump advisers, is that he didn’t use military forces and other federal assets to crack down harder than he ultimately did in the summer of 2020” on racial justice protests. Trump’s secretary of defense at the time did not agree with the president’s idea to shoot Black Lives Matter protesters near the White House.

Meanwhile, earlier this week, Trump secretly signed a directive approving the Pentagon’s use of military force on foreign soil to target drug cartels, especially in countries like Mexico.

All of this comes as Trump is due to meet Friday with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska to discuss a ceasefire in Ukraine, where the U.S. has also sent troops.

Today, we take a rare look at U.S. special forces deployed around the world, whether we’re talking about Mexico, Ukraine, Iraq, Afghanistan or here at home. They’re stationed at the most populous military base in the country, which was renamed Fort Liberty in 2023, until Trump’s Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth directed the Army to change the name back to Fort Bragg, saying, “Bragg is back.” Fort Bragg is home to Delta Force, the most secretive black ops unit in the military, which carries out classified assassinations and other clandestine missions and is also heavily involved in drug trafficking, as our next guest reveals in his new book.

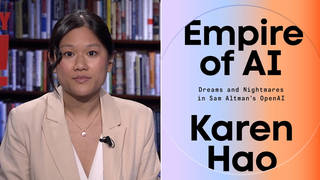

Rolling Stone investigative reporter Seth Harp is a foreign correspondent who’s reported from Iraq, Mexico, Syria and Ukraine, also an Iraq War veteran. His new book, out this week, is titled The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces.

I don’t think people usually expect to see, when talking about a cartel, the largest U.S. military base, Fort Bragg. So, if you can talk about drug trafficking and murder in the Special Forces? Begin with what Fort Bragg is, who the Special Forces are, especially Delta Forces, and who these dead bodies are that are turning up all over Fort Bragg and the surrounding area.

SETH HARP: Well, Trump says he wants to deploy military forces to countries like Mexico to crack down on drug cartels there, but I think he should look closer to home, because there’s at least 14 cases that I’m tracking of Fort Bragg-trained soldiers who have been either arrested, apprehended or killed in the course of trafficking drugs in the last five years or so, often in conjunction with those very same Mexican drug cartels.

This is especially concerning because of what Fort Bragg is. It’s not only the largest U.S. military base, but it’s central to U.S. operations and special operations. It’s the home of the 82nd Airborne Division, which is the United States’ main contingency force. It’s also the headquarters of the Green Berets, the Special Forces, as well as the Joint Special Operations Command, which includes Delta Force, which is the most —

AMY GOODMAN: That’s JSOC?

SETH HARP: That’s JSOC. That’s the most secretive and elite component of the U.S. military. And as you said, there have been some members of Delta Force who have been involved in trafficking drugs recently.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you begin this book with the discovery of two bodies. Tell us when they were discovered and who those men were.

SETH HARP: In December of 2020, two dead bodies were found in a remote training range of Fort Bragg. One of them was a member of Delta Force. They had both been shot to death. And the limited information from police at that time was that it was believed to be a double homicide from a drug deal gone wrong. The other person who was killed at that time was Timothy Dumas, who was a support officer, a logistics officer, for JSOC. The other one, the Delta Force operator, his name was Billy Lavigne. And my book mostly is, or at the core of it, it’s an investigation into who committed these murders.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Billy Lavigne, Delta Force. Talk about the Delta Force operations. And you just mentioned that people are being killed in Fort Bragg, and part of the killing responsibility is the Mexican drug cartels, but those cartels, you talk about being trained at Fort Bragg?

SETH HARP: Mm-hmm. Well, it’s unclear who committed the murders of Billy Lavigne and Timothy Dumas, I’ve got to say. Certainly, we might suspect that it could have been some of their associates in the drug trafficking industry. I did learn in the course of researching the book and reporting it that Lavigne and Dumas were buying cocaine through the Los Zetas cartel in Mexico, which, in fact, was trained in the United States. It began as a project, a joint project, between the U.S. Special Forces and the Mexican government to create an elite paratrooper unit of the Mexican Army, and later went rogue and became one of the most feared cartels in Mexico, Los Zetas.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you’re talking about a kind of Mexico Delta Force.

SETH HARP: You could say that. You could say that, or Mexican Green Berets.

AMY GOODMAN: The numbers that you’re talking about of soldiers who have died at Fort Bragg, in a couple years over 100?

SETH HARP: A hundred and nine from 2020 to 2021. And only four of those deaths took place in foreign combat zones, in Afghanistan and Syria. All the rest took place stateside, either on Fort Bragg itself or in Fayetteville, which is the town right by Fort Bragg.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you talk about, with this number of deaths, how does it compare, for example, to Fort Hood? And talk about what happens when you have this massive number of deaths. Who is held responsible? And how are they dying?

SETH HARP: Well, so far, nobody has been held responsible. Fort Bragg is the largest military base; however, the number of deaths there, on a per capita and absolute basis, outstrips any other that you might compare it to. For example, we’re well aware that in Fort Hood in 2020, 38 soldiers died. That led to extensive news coverage, as well as two congressional investigations, which ultimately concluded with the entire chain of command at Fort Hood being fired. Even though the situation at Fort Bragg is objectively worse, and has been for years, so far, to my knowledge, nothing has been done about it.

AMY GOODMAN: You say that “Fort Bragg has a lot of secrets. A lot of underground narcotics secrets. It’s its own little cartel.” That was Freddie Huff, who is the ex-DEA agent, talking about Fort Bragg. What exactly does that mean?

SETH HARP: So, Freddie Huff was a corrupt North Carolina state trooper and DEA task force agent who became a high-level drug trafficker in North Carolina. He was the connection between Los Zetas in Mexico and this group of Special Forces soldiers on Fort Bragg who were trafficking and distributing drugs in the area. And that quote was from Mr. Huff. And, you know, he was alleging that he sold, you know, hundreds of kilograms of cocaine to this group.

AMY GOODMAN: How many people die of suicide, and how is that dealt with, in the military at Fort Bragg?

SETH HARP: A shocking and depressing number. You know, the Army is well aware that it has a suicide problem. It has for a long time. But the numbers at Fort Bragg are really extreme, and it’s the number one cause of death at Fort Bragg by far. And many of those deaths are also drug-related, regrettably.

AMY GOODMAN: So, why isn’t there investigation going on? As President Trump tariffs Mexico and increases tariffs on Canada, talking about fentanyl, talk about what’s happening at Bragg.

SETH HARP: Well, on the contrary, there haven’t been. Not only has there not been any sort of reforms or any crackdown on this, but Trump and Hegseth, they make a big show of their support for Fort Bragg, changing the name back to Fort Bragg from Fort Liberty, giving speeches there, touting the Special Forces and the Airborne Corps, without really taking seriously some of these underlying and systemic issues, which are quite troubling.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the ways you use these murders to talk about U.S. presence in the military around the world is when you talk about Timothy Dumas — you say he was a quartermaster with the Special Forces — and how he used his position — was it in Afghanistan? — to bring drugs into the United States. Now, this is the guy who was murdered.

SETH HARP: Yes, that’s the allegation. Not only did — not only was he involved in that, actually, Timothy Dumas, before he died, wrote a letter, a blackmail letter. It was with the intention of blackmailing the Special Forces, because he had been kicked out of the Army for his misbehavior and his crimes and had been deprived of his pension as a result of that. In order to — in a stratagem to exert leverage on the Special Forces and get his pension reinstated, he composed this document, which purported to name the members of what Mr. Huff called the “Fort Bragg cartel.” But before he was ever able to release that letter, he himself was murdered.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s talk about Afghanistan for a moment. Talk about the U.S. presence there, the forever war, and talk about heroin, drugs and how they became so critical to the Afghan economy. And did the Taliban have anything to do with that?

SETH HARP: It’s really shocking, the degree to which the war in Afghanistan had to do with drugs and drug production. It’s an aspect of the war that was never covered to the degree that it ought to have been. Afghanistan under U.S. occupation became by far the biggest narco-state in the world, producing more heroin than the entire planet could absorb. Most of the drug trafficking and drug production was being carried out and done by warlords, police chiefs, militia commanders, who were on the U.S. payroll in a corrupt structure, which you could plausibly describe as a cartel, that went all the way up to the president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, and his brother, as well as Ashraf Ghani. During the entire time that the U.S. occupied the country, it was turning out staggering quantities of very high-potency heroin, which flooded the entire planet and caused terrible heroin crises all over the world, including in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: You write, “No person in any position of influence dared to suggest that the scourge of opiate addiction then afflicting the poor and working class across the United States might have resulted from the wartime narcotics bonanza.”

SETH HARP: Right. And part of that has to do with the DEA’s assertion that only 1% of heroin in the United States comes from Afghanistan. This is something that we were told by the DEA during the course of the war, and which was duly repeated by many media outlets. But I go into some detail in my book about why I believe that that number was fictitious. And in fact, just as in Canada, just as in Australia, Russia, wherever you look in the world, by far the majority of heroin in the United States, I believe, came from Afghanistan.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to move over to Ukraine. You have the summit that President Trump is holding with Vladimir Putin in Alaska tomorrow. You spent a good amount of time in Ukraine. Talk about where you were, when you were there, and what the U.S. Special Forces were doing there.

SETH HARP: I was in Ukraine at the start of the war. I was in Kyiv during the Battle of Kyiv. And at that time, we had been told that there were no U.S. military forces in Ukraine, that they had all been withdrawn on orders of President Biden before the Russian invasion. However, I was the first to report that, in fact, there were members of the Joint Special Operations Command active in Ukraine from day one, including members of the Delta Force, as well SEAL Team Six. And that reporting was subsequently confirmed by other media outlets. They may not have specified what units they came from, but certainly the presence of U.S. special operators in Ukraine has been confirmed.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk more about the significance of this, where they came from in the United States, what they were doing.

SETH HARP: Well, they all come from Fort Bragg. And the conventional troops that were there in Poland to back up the Ukrainian army also came from Fort Bragg, the 82nd Airborne Division. That’s an illustration of the centrality of Fort Bragg to all U.S. military operations. Now, where are they in the country of Ukraine right now? That’s not — I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know that anybody knows that. But certainly, it is concerning that we have our U.S. military personnel there in a conflict with another nuclear-armed power.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to President Trump’s relationship with the military. There’s the op-ed in The New York Times today talking about how it was thought it would ultimately, interestingly, be the military that would stop Trump from using it on the ground in the United States. The headline is “We Used to Think the Military Would Stand Up to Trump. We Were Wrong.”

And I wanted to go back to — well, we’ve talked about The New York Times revealing a trove of confidential military interviews with the Navy SEALs who accused Chief Edward Gallagher of war crimes. He met with President Trump at Trump’s private resort in Mar-a-Lago weeks after Trump overruled his own military leaders and blocked them from disciplining Gallagher, despite him being — despite him being convicted of posing with a teenage corpse in a high-profile war crimes case. He was also accused of fatally stabbing the captive teenager in the neck and shooting two Iraqi civilians, but he was acquitted of premeditated murder. In the never-before-released videos, the soldiers tell Navy investigators Gallagher was “toxic” and “freaking evil.” So, he was a Navy SEAL. You served in Iraq. You also report on Iraq. Talk about the significance of this pardoning, ultimately, that Trump did of Gallagher, and who exactly he was, and where he was found guilty of committing these crimes in Iraq.

SETH HARP: Trump’s cozying up to war criminals like Eddie Gallagher is the one — one of the most deplorable features of his administration and is an illustration of the incredibly deleterious effect that Trump’s malignant command influence has had on the entire special operations community, because Eddie Gallagher is somebody who was turned in by his own teammates, who were far from bleeding-heart liberals. These are active-duty Navy SEALs fighting in Mosul, in Iraq, who see their chief murdering people right and left, men, women, children, unarmed people. He was caught on video about to stab that teenage ISIS fighter in the neck. His teammates wanted him gone. The Navy SEAL command wanted him gone.

But Trump saw an opportunity to make guys like Eddie Gallagher part of his personal political brand. And that is — he also pardoned people like Mathew Golsteyn, who was the Green Beret officer who admitted to committing murder on live television. Other people that Trump has made part of his retinue, some of the craziest people in the special operations community.

All of this has had the effect of — you know, there are people in this community who do go by a sense of ethics and who are not so criminally inclined, and the more Trump is in office and doing things like this, the fewer you have of those people, and the more you have of the sort of piratical types like Eddie Gallagher staying in and rising higher in the ranks. And you see that in the kind of fallout of the domestic crime that I describe in my book.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Seth Harp. He is the author of The Fort Bragg Cartel. It’s out this week. The subtitle, Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces. What did you discover, Seth, about the intelligence role of Delta Force and its covert actions in countries where the U.S. is not at war?

SETH HARP: It’s really incredible how little we know about the Delta Force. I believe my book is the only sort of serious investigative look at the unit, despite the fact that it is the most elite unit in the U.S. military and has been at the forefront of all U.S. wars since at least 2001. So, Delta Force, I’d be happy to tell you anything about the unit. What was your — what should I say?

AMY GOODMAN: You tell us. You did the — you wrote the book.

SETH HARP: The intelligence gathering, you said.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

SETH HARP: So, it’s interesting, because a lot of people are not aware the extent to which these type of units, Delta and JSOC, which Delta is a part of JSOC, are — besides their paramilitary capacities, besides their operations doing assassinations and abductions in war zones, they also have strong intelligence-gathering capabilities and are — they have troops that are overseas, that are active-duty U.S. military members who are not wearing uniforms, who are not carrying IDs, who are operating under cover identities, sometimes pretending to be American businessmen, other times pretending to be State Department employees, but, in fact, are carrying out military operations in countries with which the United States is not at war, including things like bugging missions, other things that we don’t know about.

And I think what’s most crucial to emphasize in this context is that, unlike the CIA, unlike other civilian intelligence agencies that are subject to congressional oversight and must report their covert actions to Congress, the military is largely exempt from that type of oversight. And so, I think that’s one reason why you have seen a lot of the authority over covert action shift from civilian agencies to JSOC over the last 20 years.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we wrap up, I wanted to go to these latest moves by Trump, I mean, that special secret directive. We’re using it today to talk about what’s happening at home when it comes to drug cartels. But what about — and you’ve reported from Mexico. What about what Trump is saying, that the Pentagon can deploy in countries like Mexico? The Mexican president said — you know, had a very fierce reaction against this, going after drug cartels there. You started talking about Fort Bragg being a place where some of the most dangerous of these cartels were actually trained.

SETH HARP: Mm-hmm, that’s right. Los Zetas were trained at Fort Bragg, at Fort Benning, and they also received training from Israeli instructors, before they went rogue — another indication or another illustration of how U.S. military intervention often stimulates drug production. What was the second part of your question? Or what was the —

AMY GOODMAN: Well, talking about Mexico, and the U.S. deploying troops there.

SETH HARP: I mean, it’s complete — to the extent — in these days, with the genocide in Gaza and so many other things going on, we almost have lost sight, and it seems like nobody cares about international law. But I just want to point out kind of the obvious, that using military force against drug traffickers, however bad you think drug traffickers are, that’s a total violation of the laws of war. They’re not combatants in war; they’re criminals. So, that’s one thing.

Another aspect of it is, you know, the sort of typical Trump showmanship. It’s not clear to me, having worked in Mexico as a reporter for years, that the sort of cartels that the DEA creates organization charts to illustrate and tout and purport — I don’t know that those really are such coherent organizations as they might imagine, and I question whether they have the intelligence on these purported organizations where they could actually carry out military strikes on them. I don’t know that they actually have the targeting intelligence for that to become a reality. But in any event, they ought to look more closely at the drug crime that’s taking place in the United States and even on our own military bases.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about the long U.S. history, military and clandestine operations and drug trafficking in Southeast Asia, for people who are not aware of what happened, as well as in Latin America, for example, the illegal funding and support of the Contras in Nicaragua, and the thousands of Nicaraguans who were killed?

SETH HARP: Sure. There is a long pedigree of this kind of thing, covert alliances between U.S. Special Forces and paramilitaries and intelligence agencies and foreign forces that are implicated in the international drug trade. As you indicate, one of the first examples of that was in Laos and in Cambodia and Vietnam during that era, as well as in Central America, the case of the Nicaraguan Contras.

However, I must say, all of it pales in comparison with the complicity of the — practically the whole of the U.S. government with heroin cartels in Afghanistan during the war there. The amount of drugs that were produced, the openness of the alliance between the United States and known drug traffickers in that country surpass anything that we had previously seen in American history.

AMY GOODMAN: What most surprised you, Seth, in your research for this book? You, as a member of the military, but then stepping outside, you became a lawyer. You were an assistant attorney general in Texas, but a longtime investigative journalist around the world.

SETH HARP: The stuff about Afghanistan, I think, was the most shocking to me, because it was one country where I had not worked, and I really wasn’t aware of the degree to which the U.S. client state was the entity responsible for producing most of the drugs in Afghanistan. I have been kind of snowed, like everybody else, with this narrative that it was the Taliban that was doing it. But in the course of writing the book, the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan, and the Taliban in 2023 had completely eradicated all drug production from Afghanistan. So, seeing the Taliban come into power and totally eliminate that massive drug-producing industry that the U.S. had not only tolerated, but supported for 20 years, really showed — I guess, really belied the claim, until then, that it was either the Taliban or it was both sides, when, in fact, it was really our guys that were doing it the entire time.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think with this special directive, a secret directive that Trump has signed, that special forces operations in Latin America will increase under the guise of fighting cartels?

SETH HARP: It’s possible. I find that to be a very complicated prospect. So many of the drug traffickers in Latin America are military or police forces that are allied with the United States. Things are changing in Mexico and in Colombia, but, historically, the biggest drug traffickers in the Americas have been, let’s say, the Colombian Army and right-wing paramilitaries affiliated with the Colombian military, as well as, you know, you see the same type of phenomenon in Honduras and El Salvador and also in Mexico. So, when they talk about targeting these people, who exactly are they talking about?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you’ve set us up well for our next segment. I want to thank you so much, Seth, for joining us. Seth Harp, Rolling Stone investigative reporter, his new book is just out. It’s called The Fort Bragg Cartel: Drug Trafficking and Murder in the Special Forces.

Up next, we go to Colombia to speak with Senator Iván Cepeda about the sentencing of the former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe to 12 years. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Yemayá” by the New York-based MAKU Soundsystem, performing in our Democracy Now! studio.

Media Options