Guests

- Miguel Tinker Salasemeritus professor of history at Pomona College.

- Alejandro Velascoassociate professor at New York University, historian of modern Latin America.

Democracy Now! discusses the attack on Venezuela with two Venezuelan American scholars: Alejandro Velasco, an associate history professor at New York University, and Miguel Tinker Salas, emeritus professor of history at Pomona College. The professors react to President Trump’s comments on the presence of oil in the region and claims that Venezuela had “stolen” oil from U.S. companies. “There was no taking of 'American property or American oil' — it was Venezuelan oil,” says Tinker Salas. “It belonged to Venezuela.”

Velasco also comments on Marco Rubio, a central figure in the U.S. campaign against Venezuela, who may have another country as his ultimate target. “Rubio’s primary interest in the region is not Venezuela, it’s not Colombia, it’s not Mexico — it’s Cuba,” says Velasco.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

As we talk more about the U.S. attack on Venezuela and the abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, they are now, as we broadcast, being brought into the federal courthouse in New York, brought by helicopter from Brooklyn, where they have been placed in the Metropolitan Detention Center. We want to go back to President Trump speaking about Venezuela’s oil on Saturday, hours after the U.S. attack.

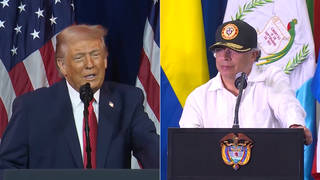

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: In addition, Venezuela unilaterally seized and sold American oil, American assets and American platforms, costing us billions and billions of dollars. They did this a while ago, but we never had a president that did anything about it. They took all of our property. It was our property. We built it. And we never had a president that decided to do anything about it. Instead, they fought wars that were 10,000 miles away. We built Venezuela oil industry with American talent, drive and skill, and the socialist regime stole it from us during those previous administrations, and they stole it through force. This constituted one of the largest thefts of American property in the history of our country, considered the largest theft of property in the history of our country. Massive oil infrastructure was taken like we were babies, and we didn’t do anything about it. I would have done something about it.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s President Trump talking about the theft of Venezuelan oil, talking about it as our oil.

We’re joined by two guests. In our New York studio, Alejandro Velasco, associate professor at New York University, where he’s historian of modern Latin America, former executive editor of NACLA Report on the Americas, author of the book Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. He was born and raised in Venezuela. And Miguel Tinker Salas is with us, emeritus professor of history at Pomona College in Claremont, California, author of The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture, and Society in Venezuela and the book Venezuela: What Everyone Needs to Know.

Welcome back, both of you, to Democracy Now! Professor Miguel Tinker Salas, oil is what you’ve been covering in Venezuela for decades. Talk about Trump’s comments that it’s Venezuela’s oil that will fund the U.S. running Venezuela.

MIGUEL TINKER SALAS: Well, we heard this with Bush in the Iraq invasion, that the oil from Iraq was going to finance the intervention and the long-term rebuilding. The reality is that that failed in Iraq, and it will fail in Venezuela. Venezuela’s oil industry has taken a hit in the last 15 years. It is a semblance of what it used to be. And the reality is, I cannot imagine any American oil company going into Venezuela, spending billions of dollars to build up an infrastructure without American boots on the ground or without very clear guarantees, and even if they did, the process would take close to a decade. So, Trump is talking the same way he always does. It is an exaggeration. It is an outright lie. And I believe it to be simply another pretext, another excuse, to try to convince the American public that what he did had any value.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Miguel Tinker Salas, I wanted to ask you again something that we discussed on Saturday in our special report on the Venezuela invasion, this whole notion of Trump, the lie that he keeps foisting on the American public that it was the socialist government of Venezuela that took this oil, when, in reality, the nationalization of Venezuela’s oil industry occurred long before anyone had heard of Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution. Could you talk about that history, as well?

MIGUEL TINKER SALAS: Sure. Venezuela was — Venezuelans were always keen on gaining control over its own oil industry. Without a doubt, American and Europeans were present at the beginning of the oil industry, but the actual work was done by Venezuelans. The actual establishment of the industry was done by Venezuelans. And there was always an aspiration that that oil industry would belong to the country, and the country could benefit from that more than simply providing concessions to foreign oil companies.

So, the nationalization happened in 1975. It was a fully compensated nationalization, taking effect on January 1st, 1976. And it was done under the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez, a social democratic government, not Hugo Chávez. Chávez did do — close the door to openings that were there for American foreign companies in Article 5 of the reform. And in 2007, there was a clash with ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips over oil deposits in the Orinoco Basin, and Chevron — I’m sorry, Exxon demanded $16 billion. A court decided that they only owed $1.6 billion. So, you can see from the very beginning that the process of nationalization had been compensated and negotiated, so there was no taking of, quote-unquote, “American property or American oil” — it was Venezuelan oil. It belonged to Venezuela, and it was the purview of the Venezuelan government to decide who or what operated those oil fields.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Miguel, I also wanted to ask you about other resources that have not been mentioned, but that, clearly, American capitalists are salivating over the prospects of getting access to. One is coltan, a rare metal that is in most laptop computers and phones, and has uses for the military, as well as diamonds and gold. Could you talk about the the immense resources that Venezuela has in these other areas?

MIGUEL TINKER SALAS: Oil is only on the surface. The reality is, as you point out, Venezuela is rich in gold. It’s rich in rare earths, rare minerals. It is rich in gas, one of the largest deposits of gas in the world. It is rich in lithium. It has potential for tremendous lithium. It has coal. It has other minerals, as well. So that the positioning of the U.S. as a investor in Venezuela or as a corporate interest in Venezuela is massive. It involves not only the country’s strategic position in its interface between the Caribbean and South America, but it involves the possession of tremendous mineral deposits and oil deposits. It reminds me of what the American general in charge of the Caribbean during World War II said: “Of all the countries of Latin America, I only want one ally, and that is Venezuela, because they’re beautifully rich in oil and minerals.”

That has been the position of the U.S. government since 1940 until the present.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d also like to bring in a professor, NYU professor Alejandro Velasco, into the conversation. Professor Velasco, on Saturday evening, you posted on social media that it seemed as if, quote, “Maduro was given up by the remaining government apparatus in a back-channel deal.” Do you still think that? And what would that mean? And is it your — do you believe that Delcy Rodríguez, who is now the — will be now sworn in as interim president, was herself complicit in this operation?

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: Obviously, it’s somewhat speculative, but clues point in some kind of direction that suggests that that might be the case. One of the things that we do know is that months leading up to, of course, the abduction of Nicolás Maduro, Maduro and people like Delcy Rodríguez, Jorge Rodríguez and others —

AMY GOODMAN: Explain Jorge Rodríguez. Her brother?

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: Yeah, Jorge Rodríguez is Delcy’s brother. Both of them have a —

AMY GOODMAN: He’s head of the National Assembly.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: He is head of the National Assembly but has held many posts under Chávez’s government and then under Maduro’s government for years. Both of them have a long, storied tradition of leftist politics in Latin America, in Venezuela in particular. Their father was a Marxist guerrilla who was assassinated under the government in the 1970s and were closely allied with the United States. And they’ve really cemented a position in government as being right-hand people to Maduro, for sure, but Chávez before him.

But what we have seen in the months leading up to the abduction was that Maduro and these inner circle members had been negotiating with the Trump administration, things like oil deals, things like other kinds of investment from the United States. But the missing piece there seemed to be whether Maduro would remain in power. And given how quickly the operation unfolded on Saturday and how quickly it seems that Delcy Rodríguez has been able to consolidate power over the intervening 48 hours, you have to assume that there was some kind of collusion, or at least some kind of conversation happening between the parties beforehand — Maduro in exchange for remaining in power, Maduro in exchange for stability, Maduro in exchange for some kind of, you know, open dealing with the United States.

Now, of course, the challenge for Delcy and others is: Can they straddle this line between doing, in some ways, Trump’s bidding, and then, at the same time, maintaining, as Andreína Chávez was saying earlier, a position of sovereignty and mutual respect of bilateral relations between Venezuela and the United States? I don’t know if they’ll be able to do it.

AMY GOODMAN: And where —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Alejandro —

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead, Juan.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Alejandro, I wanted to ask you also, in terms of the ability of Venezuela to maneuver through this situation right now. You have also raised the issue that Cuba is also in the focus of the United States in terms of what it’s doing in Venezuela. Could you talk about that, as well?

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: I have long maintained — and this isn’t secret to anyone — that Marco Rubio’s primary interest in the region is not Venezuela, it’s not Colombia, it’s not Mexico — it’s Cuba. As a Cuban American and long, stridently an opponent of the Castro government, and, of course, now the current government in Cuba, he’s made no secret of his desire to oust the government in Cuba.

The problem, of course, for him is that Cuba has no resources that Trump would be interested in, and so he would have to sell Trump only on the basis of ideology: We have to, you know, kill a leftist government. And he now sees an opening with Venezuela. He’s now able to say, “Look, if we can deliver resources from Venezuela through a low-level — deadly, of course, but low-level engagement, we can do something similar in Cuba and at the same time deliver not just Cuba and Venezuela, but the rest of the hemisphere to a Trumpist vision of the world.” That is my sense of what is largely at stake here.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you have Marco Rubio, hours after the bombing of Venezuela and the abduction of President Maduro and his wife, speaking in the news conference with Trump, saying, basically, Cuba better watch out. And then, on Sunday, you have President Trump speaking on Air Force One.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Cuba is ready to fall, you know.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: Yes!

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Cuba looks like it’s ready to fall. I don’t know how they — if they’re going to hold out. But Cuba now has no income. They got all of their income from Venezuela, from the Venezuelan oil. They’re not getting any of it. And Cuba, literally, is ready to fall. And you have a lot of great Cuban Americans —

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: Yes.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: — that are going to be very happy about this.

AMY GOODMAN: And then you have President Trump also threatening the Colombian president, Gustavo Petro.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Colombia is very sick, too, run by a sick man who likes making cocaine and selling it to the United States. And he’s not going to be doing it very long, let me tell you.

REPORTER: What does that mean? He’s not going to be doing it very long?

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: He’s not doing it very long. He has cocaine mills and cocaine factories. He’s not going to be doing it very long.

REPORTER: So, there will be an operation by the U.S. in Colombia?

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: It sounds good to me.

AMY GOODMAN: So, in a lengthy series of lengthy posts on X — I think it was like 700 words — Colombian President Petro blasted Trump, saying, quote, “Stop slandering me, Mr. Trump.” Petro called on Latin America to unite against the U.S., saying the region risks being, quote, “treated as a servant and slave.” So, go from Cuba to Colombia and what this means.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: Well, certainly, in the case of Cuba, what President Trump said is accurate insofar as most of the revenue that Cuba had been getting over the past five, 10, 15 years was coming through the subvention of Venezuelan oil. And, of course, if they close that small spigot that had been a lifeline of Cuba, then Cuba’s position is incrementally worse. And you might end up seeing protests, as we’ve seen in prior years, and, as a result, then, a kind of pretext for intervention.

But then, if you link that — and what Cuba represents to Latin America, which is a kind of paragon of a different alternative for Latin America as a region, a leftist alternative, with all of its faults, that we can, of course, talk about at length. Losing that for the region would then open up the door for other countries and other right-wing countries in Latin America — or, right-wing movements in Latin America to say, “Now we have a White House in power, and no Cuba present in the region, or leftist government in the region, to be able to do what we want.” And so, to me, this is far, far larger an ideological project and battle that’s being waged, with Venezuela as a kind of instrumental piece.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, I’d like to bring Miguel Tinker Salas back into the conversation, and this whole issue of Trump focusing not just on Venezuela, but also on Cuba, Colombia, and how Latin America, you expect, will respond. Because, clearly, this is not the same Latin America, as I said repeatedly, that existed 50 years ago or 60 years ago. There’s many more popular movements, stronger progressive leaders in several countries. What’s your sense of how the region is going to respond in the coming weeks and months?

MIGUEL TINKER SALAS: I think there’s a difference between how political leaders may respond, because, obviously, someone like Milei or Noboa or Bukele will respond in support of Trump. It’s another thing how the population of Latin America will respond. And I think that’s the big difference here, because, as you point out, there has been a tremendous level of mobilization, of social consciousness, that has occurred. But there’s also been the weight of the crisis that has affected many countries of Latin America and left mistakes that have been made, in many cases, in many countries in their inability to deliver.

But I think we’re also overestimating U.S. empire, because what we saw in Venezuela on Saturday, the 3rd, was the spectacle of empire. It was the promotion of empire, while not actually landing troops on the ground. They were unable to do that because they know that that would bog them down in a long-term war, and taking on Cuba at the same time and taking on Iran at the same time and taking on bombings in Nigeria at the same time, and potentially conflicts in Ukraine, in Asia, in Taiwan, etc. I think we should not overestimate the role of U.S. empire. I think the military in the U.S. would push back to any kind of operation in other countries, because that will be a long-term commitment, because taking Cuba means employing the same old Colin Powell doctrine, the Pottery Barn doctrine, that was, “If you break it, you own it.” So, if the U.S. expects to have — run Venezuela, they’re also going to have to run Cuba, and they’re also going to have to run Colombia, and they’re also going to — I doubt that the U.S. military is prepared for that kind of long-term engagement.

That doesn’t mean that I don’t believe that the U.S. wants to remake Latin America, the same way that the neocons wanted to remake the Middle East. The current administration, under Marco Rubio, really wants to remake Latin America. They want it to be the American pond. They want it to be the Caribbean that they control. They want to go back to Teddy Roosevelt and gunboat diplomacy and big stick diplomacy and control the region. But again, we shouldn’t overestimate the role of U.S. empire. I think we saw on Saturday was the spectacle of empire.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: I mean, completely agree with Miguel, and that last point that he made is so central. I think what we’re seeing here is a return to this gunboat diplomacy that had been the hallmark of the Teddy Roosevelt period in the early 20th century.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to ask you, Alejandro, very quickly, about President Trump responding to a reporter about the Venezuelan opposition leader, Nobel Prize laureate María Corina Machado.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Oh, I think it would be very tough for her to be the leader. She doesn’t have the support within or the respect within the country. She’s a very nice woman, but she doesn’t have the respect.

AMY GOODMAN: I think many people were shocked that President Trump threw María Corina Machado under the bus, the woman who basically dedicated her peace prize and said that Trump should have gotten that peace prize. Where does this leave her? And also, talk about the wife of — exactly who President Maduro’s wife, Cilia Flores, is. She is a key political figure herself.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: For sure. I mean, let’s start with María Corina Machado. No one —

AMY GOODMAN: And we have 30 seconds.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: No one could have been more surprised that she was sidelined, not just at the press conference, but then doubled down yesterday, Marco Rubio also saying that she is not ready, you know, to stand in. Yeah, I think what they — what Machado overestimated was the degree to which Trump wanted democracy. He doesn’t want democracy. He just wants oil, right? And so, in that sense, you know, it was unsurprising that she would be sidelined, to anyone but her.

AMY GOODMAN: Cilia Flores? Ten seconds.

ALEJANDRO VELASCO: Cilia Flores, you know, long, storied career under Chávez, was the head of the National Assembly, significant degree of political power. We’ll see what emerges from this trial. just

AMY GOODMAN: And we’re going to talk more about this in these coming days. And also remember that President Trump just pardoned the convicted narcotrafficker, Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options