Topics

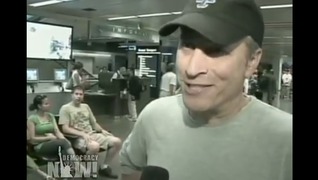

After two of her producers were arrested while covering protests in St. Paul, program anchor Goodman (pictured) sought their release and was taken into custody, too. (Image: Democracy Now!, posted on YouTube.)

Journos arrested in St. Paul aren’t ‘willing to let this go’

Originally published in Current, Sept. 15, 2008

By Karen Everhart

Videos of the Sept. 1 arrests of Democracy Now! producers in St. Paul, Minn., spread chilling evidence that police were making no distinction between the protestors outside the Republican National Convention and working journalists covering their activities.

Among approximately 40 reporters and other media-makers caught up in police sweeps during the convention were Nicole Salazar, a multimedia producer for the daily progressive news program, and her colleague Sharif Abdel Kouddous. Salazar was filming a protest when riot police rushed up and knocked her down as she called out, “Press! Press!” She screamed as the police roughed her up.

Amy Goodman, host and e.p of Democracy Now!, was arrested shortly after when she rushed up to a line of riot police to demand that they release her producers.

Videos of both arrests, quickly posted on YouTube, stirred objections to the police tactic of rounding up credentialed journalists as they worked to clear the streets of rowdy protestors.

Salazar and Kouddous face felony charges of probable cause riot — meaning that police had a reasonable suspicion that they had participated in rioting — and Goodman, a misdemeanor of obstructing a legal process. Attorneys for the city of St. Paul and Ramsey County are weighing requests to have the charges dropped, according to John Lundquist of the Minneapolis law firm of Fredrikson & Byron, who represents the Democracy Now! trio.

“There have been a number of journalists swept up and charged with unlawful assembly, but the charge is not applicable to journalists,” Lundquist said. “It’s not as if they were parading without a permit. They were trying to gather the news of those who were.”

Journalists arrested during the RNC included Associated Press reporters Amy Forliti and Jon Krawczynski, AP photographer Matt Rourke, Variety Managing Editor Ted Johnson, photographers for two Twin Cities TV stations and the St. Paul Pioneer Press, and representatives of several indie media organizations, according to the Minnesota Independent. Its list of 42 journalists arrested included college journalism students and documentarians with I-Witness Video, a group that videotaped police misconduct during the 2004 RNC in New York.

By the time the convention closed Sept. 4, some 60,000 people had signed online petitions calling on St. Paul officials to drop charges against the arrested journalists. Local media advocates delivered the petitions to City Hall Sept. 5.

St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman appointed two former federal prosecutors Sept. 9 to lead an independent investigation of public-safety planning and law enforcement tactics for the convention. The first tasks of former U.S. attorney Thomas Heffelfinger and former assistant U.S. attorney Andy Luger are to “complete the review team and set the scope of their work,” Coleman announced Sept. 8.

The Minnesota chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, which objected to the arrests during the RNC, is continuing to press the issue. SPJ scheduled a Sept. 22 panel discussion among law enforcement officials, city leaders and journalists. Al Tompkins of the Poynter Institute will moderate the forum at the University of Minnesota.

“We’re going to talk about what happened and how journalists can do their job without fear,” said Nicole Garrison-Sprenger, Minnesota SPJ president and a reporter with the Pioneer Press. “We don’t want this to happen again.”

“Journalists aren’t willing to let this go and let police think they can treat working journalists the way they did,” said Art Hughes, a former Minnesota Public Radio reporter and board member for the Minnesota SPJ chapter. Hughes was among the journalists arrested Sept. 4, the closing night of the Republican convention.

Hughes was recording sound and photographing protestors who were marching and disrupting traffic after their permit had expired, but he moved to a nearby parking lot to observe the police action from a distance. He was caught in a police line that pushed him and other peaceful observers toward the protestors.

“I had my RNC credentials on me the whole time,” Hughes said. “It made no more difference to them than a driver’s license.” Hughes received a citation for unlawful assembly.

His foot on her back

Salazar’s video provides some particulars of her arrest. As officers approached, she can be heard asking, “Where do I go? Press! Press!” She continues filming even as the police knock her over. Salazar starts screaming, and the video ends.

In an appearance on Democracy Now! after her release, Salazar said one officer stomped on her back while another pulled her by the leg. All the while, she was being ordered to keep her face to the ground. Kouddous, whose arrest occurred off-camera, told Current that he was kicked in the chest, and his arm was scraped.

“The arrest itself was chaotic,” Kouddous said. “I was screaming ‘Press!’ the whole time and ‘Look at my credentials!’”

Goodman and Kouddous said their credentials were confiscated by a plainclothes officer. They said police told them he was from the Secret Service.

The video of Goodman’s arrest shows her approaching the police line as an officer points to direct her to step back. As someone shouts “Release the accredited journalists!” the officer grabs Goodman, pulls her behind the police line and takes her into custody as she objects, “Don’t arrest me!”

During the 2004 RNC in New York, Goodman had been able to talk to police and get her producers out of a similar situation, she told Current. That was her objective in St. Paul. She had been interviewing Republican delegates inside the convention site when she heard about the arrests and raced to the scene.

“If there was some confusion, I came to vouch for them and to say, ‘They are accredited journalists,’” Goodman said. “I was making sure that they were okay.”

The whole episode was frightening, she recalled, because she and other journalists were prevented from doing their jobs. “Our job is to be there to chronicle and monitor what is happening and to present that,” Goodman said. “We have to be able to put things on the record without getting a record.”

Hughes, now a freelance journalist, said the St. Paul convention arrests have put reporters on notice that police have changed their treatment of reporters covering street protests.

“There was a time when journalists would get into the thick of things, and there was recognition that they weren’t there to do harm and weren’t a threat to anything,” Hughes said. The ground began to shift after the 1999 street protests of the World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle and the 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C., he said. In recent years it’s become increasingly difficult to distinguish professional reporters from citizen journalists or media activists who bring cameras and political agendas to protests.