As efforts grow to target activists who expose animal abuse, we speak to Andrew Stepanian, who was sentenced to three years in prison in 2006 for violating a controversial law known as the Animal Enterprise Protection Act. Stepanian and several others were jailed for their role in a campaign to stop animal testing by the British scientific firm Huntingdon Life Sciences. They were convicted of using a website to “incite attacks” on those who did business with Huntingdon Life Sciences. Together, the group became known as the SHAC 7. He was held for part of his sentence at a secretive prison called a Communication Management Unit in Marion, Illinois. The highly restrictive prison holds mostly Arab and Muslim men. The environmental activist Daniel McGowan was also held at a CMU. In December, McGowan was released to a New York City halfway house after spending five-and-a-half years in prison for his role in two acts of arson as a member of the Earth Liberation Front. Last week, McGowan was briefly detained again just days after he published an article for The Huffington Post about the CMUs.

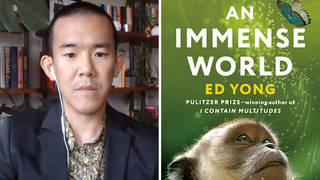

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. Our next guest was sentenced to three years in prison in 2006 for violating a controversial law known as the Animal Enterprise Protection Act. Andrew Stepanian and six others were jailed for their role in a campaign to stop animal testing by the British scientific firm Huntingdon Life Sciences. They were convicted of using a website to, quote, “incite attacks” on those who did business with Huntingdon Life Sciences. Together, the group became known as the SHAC 7. Andy Stepanian was held for part of his sentence at a secretive prison called a Communication Management Unit in Marion, Illinois.

Animal rights activism is back in the news this week. A front-page article in The New York Times called “Taping of Farm Cruelty Is Becoming the Crime” notes that a dozen or so legislatures have introduced bills that target people who go undercover to expose farm animal abuse. These so-called “ag-gag” bills would make it illegal to covertly videotape livestock farms or apply for a job at one without disclosing affiliations with animal rights groups. And Andrew Stepanian joins us right here in our New York studio.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Thanks for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good to have you with us. Can you talk about what is happening, the trend across the country and efforts to stop animal cruelty?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, well, I’ll let Will Potter expand upon this, but generally what’s happening is that we’re seeing groups, middle agencies, like the American Legislative Exchange Council, penning model legislation that behooves animal enterprises. So, if it’s a factory farm or laboratory or someone that profits off the use of animals, then there is designer statutes, designer legislation, that’s being written, introduced and passed, you know, fast track through Congress or through states, individual states—in this case, the ag-gag bills are mainly state bills right now—that are targeting animal rights activism and targeting undercover investigators.

Over the past 10 years, there’s been a bit of a shift in animal rights activism from some of the more radical tactics to relying on more legal approaches like using videography to expose cruelty inside factory farms and laboratories. And this is integral to some of the largest animal rights organizations in this country, like Mercy for Animals, Compassion Over Killing and PETA. They rely heavily on this tactic to showcase that animal abuse is not only rare and not a marginal thing happening in these institutions, but it’s systemic. It’s systemic problems that need to be documented and need to be treated accordingly. This is causing these businesses a great deal of profit, and so they’re lobbying, in result, to create laws that will then cull the ability of either journalists or activists to document this cruelty and get it out to the public.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the things that people are concerned about is that if you do an undercover video, you have to show it in like—within 48 hours.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, some—

AMY GOODMAN: What is the problem with this?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Some of the most recent legislation is saying that you have to release this within the first 24 hours. And this is problematic for the investigators because, you know, this is not—what they need to do is they need to be able to show the cruelty and then do a larger investigation that shows that the problem is systemic. That’s the only way that we’re going to be able to get widespread animal welfare and animal rights legislation that benefits animals in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Meaning someone could say, “Oh, that was a rogue worker—

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —”who did that for one day.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: And that’s generally—

AMY GOODMAN: “And we stopped that.”

ANDREW STEPANIAN: That’s generally the answers that we’re hearing, is that, “Oh, it was one mistake,” or “It was one rogue worker, and this is not indicative of a systemic problem.” The truth is, is that in—and this is in part because of capitalism, but capitalism is rewarding bad practice, whether it be in capital markets or it be in the way that animals are treated. And so, as a farmer—and you’re seeing this is—mom-and-pop farms are becoming more and more marginal and making way now for these larger factory farms, making up over 90 percent of the farms here in the United States are these factory farms, where they’re condensing the amount of animals per acreage, piling animals on top of each other. In the case of battery chickens, there are multiple animals that are in cages the size of television sets on top of one another, maybe seven tiers high, all with latticeworks of chicken wire between them. Some of the animals—and I’ve witnessed some of this myself—some of the animals on the lower levels are devoid of any feathers or fur or anything else, because the ammonia from the feces that drips down from the top levels actually just strips them of their plumage. And this is something that’s not rare; this is something that’s systemic. And it’s because they’re trying to crunch to make profit margins and also, you know, yield to whatever demand there is out there for these products. And so, what we need to do is we need to be able to show this is not a rare thing, it’s not a one-off thing. This is all the time. And we need to address these problems. Whether you’re vegan or vegetarian or you’re a carnivore, I think most people can agree that cruelty to animals is wrong.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you talk about your own case for a moment? What happened to you? What were you convicted of?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well, I was convicted of using a facility in interstate or foreign commerce for the purposes of causing more than $10,000 worth of damage to Huntingdon Life Sciences, which was a biotech firm that was doing testing on animals. They had a facility in New Jersey, three in the U.K. and a satellite office in Tokyo. What they alleged my personal involvement was, was that I organized demonstrations against the Bank of New York and Deloitte & Touche, both of which had financial involvement with Huntingdon Life Sciences. Both companies severed their financial relationships with Huntingdon Life Sciences. And I was unapologetic about being involved with those campaigns. In one instance, I was stopped by local police. They took my ID. And I was completely transparent about being involved with this demonstration. The local police didn’t find a reason to cite me with an infraction, and they let me go. But 18 months pass. The FBI finds a reason to say that I was guilty of conspiracy.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, talk about why you were protesting Huntingdon.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: We were protesting Huntingdon Life Sciences initially because there were five undercover investigations, the first by a woman by the name of Michelle Rokke, who was wearing a hidden camera, that worked inside Huntingdon Life Sciences, depicting some of the worst cruelty to animals that was shown to date at that time. And—

AMY GOODMAN: What was that cruelty?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: It included things like punching beagle puppies in the face. It included—

AMY GOODMAN: For what purpose?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Nobody really knows. Apparently in the video, the beagle puppy is being punched in the face by one of these vivisector. The vivisector was frustrated because he couldn’t find a vein to inject the animal with, and the animal kept flailing. And so, in order to, you know, subdue the animal, he started punching the animal. All this was repeatedly shown in video footage that we then leaked to the press.

As a result of that, we had widespread support and this kind of groundswell of interest in getting involved with campaigning against Huntingdon Life Sciences. And so, for a lot of the animal rights activists at the time, they kind of saw a watershed moment where we could reach out to other people that weren’t necessarily vegan or vegetarian or identified as animal rights activists, because these are domesticated animals that people could identify with. And so, we said, “OK, here are dogs and cats. You know, people can start to get this, and they can start to understand why we think the way we think.” And so, this was kind of a springboard for other campaigns. So, it started with an undercover investigation. It led into a campaign that was now in 18 different countries at the time of our indictment. And—

AMY GOODMAN: And what was the grounds for the FBI? Police said no. Yeah, they got you at the protest. You had admitted you were involved with the protest. And since when does the FBI—

ANDREW STEPANIAN: All the FBI had to do, in the case of the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, was prove that it was my intention, or at least it appeared to be my intention, to cause more than $10,000 worth of damage to Huntingdon Life Sciences.

AMY GOODMAN: And that damage was?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: And that damage was via, specifically in my case, the group Deloitte & Touche severing their auditing relationship with Huntingdon Life Sciences and a temporary delisting of the stock from the New York Stock Exchange, or at that time the Over-the-Counter Bulletin Board. That cost them a certain amount of revenue in the time they were delisted.

AMY GOODMAN: And you went to prison.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I went to prison for 36 months, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about where you were held.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: So, initially, I self-surrendered to Cadman Plaza U.S. Marshals office. I served the beginning of my sentence at MDC Brooklyn, where the first 21 days of that sentence I spent in solitary confinement in the hole. They cited a media appearance—

AMY GOODMAN: In MDC Brooklyn.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: In MDC Brooklyn, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Metropolitan Detention Center.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: They actually cited my appearance—or, not appearance, but phone conversation with you as the reason for why they were holding me in the hole.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m sorry.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: That’s OK. It’s not your fault. They had—they had said that inmates that engage in media are subject to investigation because it might risk their safety in the prison populace. And it was kind of like this legalese boilerplate that they read off to me. But I interpreted it as they were doing this to me to penalize me for doing media in regards to my case.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, then talk about where you were moved to.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I was moved to North Carolina, where I served two-and-a-half years in North Carolina at the medium-high-security prison at Butner. From there, in May of 2008, I was then transferred to a high-security unit at the Marion United States Penitentiary called a Communications Management Unit.

AMY GOODMAN: High-security unit?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well—

AMY GOODMAN: Were you even convicted of a violent crime?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: No. Actually, at that point, because I was engaged in programming and didn’t have any ticketable offenses within the Bureau of Prisons that could lower my—or cost me good time, they had actually said to me that I was qualified now to go to a low-security prison instead of a medium-security prison. So I thought if I was going to get a transfer, I had hoped—what I had hoped, and the judge had agreed to, was for me to be designated to Fort Dixon, New Jersey, which was close to my family. And my goal was to get closer to home. I was actually 600 miles from home. It was very hard on my family to try and visit me in North Carolina. So my goal was to get to New Jersey. That’s what I thought was happening when they came to transfer me initially.

But once I saw the restraints and such that they put on me, I realized that I can’t be going to a low-security prison with these types of restraints. And when I got loaded onto an airplane, I was in the back of the airplane with a gentleman by the name of Ali Chandia. He was from the—what the prosecutors called the Virginia jihad network, a case involving paintballs sent to Lashkar-e-Taiba. I started to realize that us that were in the back of the plane were the inmates that were designated as terrorists and that we were going to a specialized unit.

AMY GOODMAN: And what were the grounds? What did the U.S. government say, why in fact you were not going to a low-security unit but a high-security unit?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well, here’s the interesting part about the Communications Management Unit, is that just prior to them building the Communications Management Unit, Marion USP was considered a maximum or the former supermax prison that was in the federal system. Currently that’s replaced by what’s called ADX at Florence, Colorado.

AMY GOODMAN: ADX stands for?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: ADX stands for Administrative Maximum. I don’t know why the X stands for “maximum,” but that’s their abbreviation. And what they did, in order to designate inmates like myself that had low-security points, others that had medium, and others like some of these Muslim men that were held there—over 76 percent of the people that were held at the CMU are Muslim or Arab nationals. The men that were there, most of them had minimum-security points.

And in order to create this administrative unit that didn’t follow the guidelines of the larger Federal Bureau of Prisons, they had to downgrade this maximum security facility to what’s called a FCI, or a Federal Correctional Institution. What they did, however, on letterhead is keep the name USP. USP gives them a certain budget. This was under the guidance of Harley Lappin, who was the director of the Bureau of Prisons at the time. They kept the name USP, which give them a certain budget; however, they got rid of some of the staff in order to bring the staff down to the levels that would be otherwise an FCI. And in this like kind of financial play area, they took the money left over to build this specialized unit. This is how they were able to bypass the Administrative Procedures Act in building this unit, because initially Congress had said no to a specialized unit called the Counterterrorism Unit, or CTU. What’s ironic now is that, through some of these FOIA documents released through the Aref v. Holder case and some of the discovery in the Aref v. Holder case, they’re still holding onto letterhead that says ”CTU.” So they haven’t really scrubbed their own documents to say that this unit—they’re just building the unit that Congress said no to. And that’s where I was designated.

Most of the inmates there are considered either inmates of inspirational significance, whatever that means, or inmates that are terrorists. But to my observation, not everyone was of inspirational significance. More often—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, “inspirational significance”?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: That’s their terminology, not my own. I don’t know if I agree with it. But that’s the Bureau of Prisons’ terminology for designation to the Communications Management Unit.

AMY GOODMAN: And you?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Myself? My interpretation was that it was a unit designed after 9/11 to house Muslims within the Federal Bureau of Prisons that they thought could possibly recruit or that they didn’t fully understand, and they wanted to vet their communications.

AMY GOODMAN: And you? Who were you in that spectrum?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: At that—at one point during my stay there, a guard referred to me as a “balancer.” And he had actually—the way the conversation was phrased was he kind of said something to me along the lines of: “Keep your head up, kid. Don’t worry. You’re not like the rest of these Muslims.” And I don’t mean this in a disparaging way; I’m just quoting the man. “You’re not like the rest of these Muslims. You’re going to go home soon enough. You’re only here for balance.” And—

AMY GOODMAN: I don’t understand.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: It was my understanding that the law—the unit was a lawsuit waiting to happen—of which it is. It’s being sued right now for discrimination because of the overwhelming demographic of Muslims that are there. And it was my understanding that the first CMU—that was at Terre Haute, Indiana—that was built was almost 90 percent or 95 percent Muslim. They realized that this became problematic, so when they built the second CMU at Marion, Illinois, that they wanted to offset part of their population with individuals that could be designated to this terrorist unit, that fit a certain criterion, like myself, that could then create this balance to say, “We don’t only have Muslims here; we have other folks.”

AMY GOODMAN: So, oddly enough, if you had converted to Islam, they might have moved you out.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I’m not sure. They had asked me—they had pulled me aside for interviews. I mean, I wouldn’t say it’s interrogation, but the investigative forces within the Bureau of Prisons pulled me aside a few times to ask me about me growing a beard while I was there, asking me if I was converting to Islam. I didn’t—

AMY GOODMAN: Because you had grown a beard.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I had grown a beard while I was at the CMU.

AMY GOODMAN: But you would no longer be balancing them, so there would be no reason for you to be there.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: They actually went as far as to try and get me to sign an affidavit saying that I was a—give me a second—Protestant. They wanted me to identify as Protestant, because in the Bureau of Prisons designation for me, under religious affiliation, they just had “other.” That was actually under the advice of my attorney, to say that I was Buddhist, that it might be able to help me get a vegan diet while I was in there. That was his theory. So we listed it as “other,” and then we included this information from the judge to try and get me vegan food.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you succeed?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, I was able to eat while I was in there, generally. I got enough calories. It wasn’t good, but I got enough calories. But I believe in God. I am, I guess, a practicing Christian. I go to church with my family. But I knew, when they were trying to get me to sign that document, that was because they were hoping to have more men listed there as not Muslim, and they needed one more on record that wasn’t a, quote-unquote, “other,” like myself.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you sign?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: No, I did not. I’m in the process right now of actually FOIAing for those documents to see if they actually signed for me.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Andy Stepanian, animal rights activist, imprisoned at a high-security CMU, Communications Management Unit, in Marion, Illinois. He’s co-founder of The Sparrow Project. Do you think you would have been treated this way if you hadn’t released undercover video of animal abuse?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well, to clarify, that that undercover footage that was released is what inspired me to get involved myself, so I wasn’t the one that released it. I saw it, and it motivated me to get involved with the SHAC campaign. So, I don’t think they attributed that footage to me. I think they understood who released that footage. So I don’t think—

AMY GOODMAN: And was that person charged?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: That person had some legal consequences, but most of it was taken care of, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: So now you’re out. What effect has your imprisonment had on you?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Mostly psychological. I mean, I have—I repeatedly have nightmares. I sleep not well. But it’s not nightmares of violence. It’s more just repeating situations that I was in, whether it be solitary confinement or, you know, this kind of urge to go home, that kind of thing, just revisiting moments in prison. So I don’t know if that would qualify as what people would normally consider post-traumatic stress disorder, because I’m not remembering, say, a stabbing or something that happened in prison. I’m remembering moments that I think were more emotionally upsetting for me.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what happened in Southern California at a slaughterhouse that McDonald’s used as a supplier and how animal rights activism led to them severing ties with this company?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: There was a group called Compassion Over Killing that sent an undercover investigator into, I believe it was called Central Valley Meats. It was a meat supplier for major fast food chains. And when that undercover investigator was there over the course of a few months, it showed systemic problems of egregious animal abuse. And while this egregious animal abuse was happening, there was actually members of the USDA or other auditing, you know, agents there, witnessing it happening but not reporting it.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m looking at an Associated Press piece, and it says, “The suspensions occurred after an animal welfare group’s covert video showed cows that appeared to be sick or lame being beaten, kicked, shot and shocked in an attempt to get them to walk to slaughter. … The video appears to show workers bungling the slaughter of cows struggling to walk and even stand. Clips show workers kicking and shocking cows to get them to stand and walk to slaughter.”

ANDREW STEPANIAN: These are all examples of systemic problems that are happening not just at Central Valley Meats, but are happening all across the country. And I think factory farm industries and the lobbyists that represent them understand that. And these things happen in order to maximize their profits. So, as these lobbyists are defending their profits, and they hire middle agencies like the American Legislative Exchange Council, they start petting bills like these ag-gag bills, that Will will be able to describe in great detail, that will target undercover investigators. They’ll target photographers, videographers, that expose cruelty like this, and try to prevent it from seeing the light of day. In some cases, one of the laws—I believe it’s in Florida—will actually go as far as saying that a journalist that redistributes or syndicates this footage is subject to criminal charges, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: And the fact that if you work at one of these companies, you have to reveal that you’re with an animal rights group, on penalty of being imprisoned, of being convicted, being indicted?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, they are trying to go one step further to try and stop these people from even getting in there to obtain this footage, by trying to have all employees disclose. And in some cases, some of the employees that have been caught doing this, there have been—even predating these ag-gag laws, there have been instances where they’ve tried to get them on false ID or breaches of terms and agreements with the company itself.

AMY GOODMAN: What does “ag-gag” mean?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I mean, ag-gag is a term that came up—it’s kind of like a trending tag right now—referring to agricultural gag laws. And what they’re trying to do is they’re trying to silence activists. They’re trying to gag them. And these laws clearly exist for the purpose of silencing and gagging what is First Amendment-protected speech and journalism that is showing systemic cruelty in order to try and make the world a better place for animals.

AMY GOODMAN: Andy, you are co-founder of The Sparrow Project. What is this?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well, Sparrow Project was kind conceived from my jail cell when I was in prison. I didn’t always have people on the phone to talk to or, you know, people to commingle with. But I often had pretty wonderful experiences with the birds that would kind of dance between the razor wire outside my cell. And they were symbols of freedom for me. And so, when I got out, through, you know, building relationships with penpals, I decided that I was going to create a kind of DIY or boutique PR agency that would represent activists and journalists, hopefully around the world. And I’ve kind of gotten off to a slow start, but I’m kind of happy with where I am now in life, because I’m trying to bring that inspiration that I saw in those sparrows and find the small things that inspire others and make the world a better place.

AMY GOODMAN: Now I want to ask you about Daniel McGowan, who was another environmentalist who was imprisoned for years but now is free—and then was just arrested on Friday. He was arrested—he was released Friday afternoon after federal authorities were notified they had arrested him under a regulation declared unconstitutional. McGowan had been taken into custody Thursday just months after his release to a halfway house following over five years in prison for his role in two acts of arson as a member of the Earth Liberation Front. In his case, the judge ruled that he had committed an act of terrorism, even though no one was hurt in either of the actions. McGowan was told he had violated a Bureau of Prisons rule for publishing an article decrying his treatment, an article that he published in The Huffington Post. McGowan’s attorneys say they won his release after pointing out the regulation in question had been declared illegal in 2007 and eliminated in 2010. Do you know Daniel McGowan?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, I actually knew Daniel McGowan before I went to prison. He was a friend of mine. And coincidentally, I actually ran into him at the CMU at Marion, Illinois. So, about for three months, we spent time together a couple cells away from each other while at the CMU Marion. He then was in the CMU Marion for about another year, was matriculated into general population at the Marion USP, and was quickly sent back to the CMU, but this time at Terre Haute, where he served out the rest of his sentence before qualifying for a halfway house. So he was in a halfway house for about three months, when—

AMY GOODMAN: Here in New York.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Here in New York, in East New York, when this happened. He was working for a law firm, was getting back, you know, on track with his life, had no disciplinary reports, was always on time, was always doing the right thing, according to his probation officers and his case manager. But Huffington Post, even while he was at the CMU, gave him a space on their blog column. And he utilized that to talk about the lawsuit he’s filing against the Bureau of Prisons. The lawsuit is called Aref v. Holder, where he and Yassin Aref are co-plaintiffs in a case brought against Eric Holder and the Bureau of Prisons for their designation to the Communications Management Unit.

AMY GOODMAN: Aref is?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Aref is a man that was entrapped in upstate New York and charged with alleged involvement with material support to terrorists. He witnessed a bank loan happening between an FBI informant and a man who owned a pizzeria in upstate New York, wherein at the offices that he witnessed the loan happening, they said there was a weapon against the wall, and he didn’t report it.

AMY GOODMAN: And why would he have had to report it?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: I’m not exactly sure. I’m not a federal prosecutor. I don’t know the nuance that actually resulted in him being charged with material support. I do know, however, that he’s no longer designated to the CMU Marion as a result of this lawsuit. They actually let him go to a medium-security prison as a result.

AMY GOODMAN: And again, then continue to explain the lawsuit that McGowan is a part of.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: So, McGowan, along with Yassin Aref and Daniel McGowan’s wife, are plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the BOP and Eric Holder.

AMY GOODMAN: Bureau of Prisons.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Bureau of Prisons, I’m sorry, and Eric Holder for their designation to the Communications Management Unit. There’s a great deal of research being done by law schools and investigators and investigative journalists right now into what exactly gets someone designated to these units. At surface glance, it looks like it’s arbitrary. But if you take a step back away from it, and you see that 76 percent of the men designated there are Muslim, you could start developing other narratives from that.

Their lawsuit is in hopes to get clarity as to why they were designated, or that perhaps allege that they were misdesignated to this unit, and to challenge the legality of the units themselves, for discriminatory purposes and also for clamping down on people’s speech. For example, at the Communications Management Unit, you’re not allowed access to telephones and contact visits like normal prisons—like normal prisoners are allowed access. You are allowed a phone call by appointment once a week or perhaps twice a week by your case manager, but it has to be done through a live monitor being present, as well as run through a hub in Washington, D.C., or West [inaudible], Virginia. And they have to be done in English. They have to be done during certain business hours in accordance to Washington, D.C. So it really—it stands in the way of people trying to call home at certain hours when their family members might be at work. So, now you have that form of communication vetted and also kind of clamped down upon. Mail, general snail mail, is vetted heavily there, barely ever making it to the inmates.

And then contact visitation is entirely barred. So, for example, even at the maximum security prisons in the federal prison system, you’re allowed to have contact visitation with your family. And, in fact, psychologists that work with the Bureau of Prisons say that this is integral to the enrichment of prisoners and part of their rehabilitative process, is contact with family. So they’re denying this completely for these men, saying that they have ties to alleged terrorist groups, etc., and they can’t have contact visitation with their family. I can’t see how that is possibly useful to the BOP for any other purpose besides being punitive. And this is part of the argument that’s in that lawsuit.

Daniel McGowan wrote an article for The Huffington Post detailing his transfer and his notice of transfer to the Communications Management Unit and some of the elements of this lawsuit, also detailing why maybe he was designated to this unit. But inside the article itself is nothing new to the BOP and nothing new to the public, because everything that’s in that lawsuit is now public record. He also included his opinions, which is protected speech. And yet the Bureau of Prisons decided to penalize him—or attempt to penalize him for publishing this article.

AMY GOODMAN: By arresting him.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Well—

AMY GOODMAN: Or taking him back into custody.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, taking him back into custody into MDC Brooklyn. What’s tough about the halfway house system is that, for anyone who’s in a halfway house, you’re not fully free yet. Anyone who’s in—

AMY GOODMAN: Were you?

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah. I actually refrained from doing any media appearances while at the halfway house, or writing while I was at the halfway house, because I knew the amount of scrutiny that I was under. I don’t know if Daniel had that same type of scrutiny that I had. Also, I can’t judge him for writing about it. I applaud him for writing about it. That said, however, the bureau likes to say—the Bureau of Prisons likes to say that as long as you’re in custody, whether it be a halfway house or the Bureau of Prisons, you’re considered a ward of the state, and you’re not awarded the rights of normal citizens. So, things like freedom of speech kind of go out the window when you’re in the Bureau of Prisons. And that’s evident by the way that people are treated at the Communications Management Unit, and that’s evident by the way that Daniel McGowan was treated while in the halfway house.

AMY GOODMAN: But ultimately, he was freed within a day.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Yeah, and that was because what they used in what they call the shot, or the ticket, that was filed against him, the incident report, was a law or an infraction number that involved publishing under a byline, which a judge struck down as unconstitutional in 2007. And so, they quickly expunged the ticket against him, and they released him or furloughed him back to the halfway house, where he’ll serve time there between there and his job, and periodically getting visitation home to see his wife and his family, until June, when he’s finally done with his sentence, and he can go about his life.

AMY GOODMAN: Andy Stepanian, I want to thank you very much for being with us.

ANDREW STEPANIAN: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Animal rights activist, co-founder of The Sparrow Project. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options