Topics

Guests

- Noam Chomskyworld-renowned political dissident, linguist and author. He is institute professor emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has taught for more than 50 years. His latest book is titled Who Rules the World?

In Part 2 of our wide-ranging conversation with the world-renowned dissident Noam Chomsky, we talk about the conflict in Syria, the rise of ISIS, Saudi Arabia, the political crisis in Brazil, the passing of the pioneering lawyer Michael Ratner, the U.S. relationship with Cuba, Obama’s visit to Hiroshima and today’s Republican Party. “If we were honest, we would say something that sounds utterly shocking and no doubt will be taken out of context and lead to hysteria on the part of the usual suspects,” Chomsky says, “but the fact of the matter is that today’s Republican Party qualify as candidates for the most dangerous organization in human history. Literally.”

To watch Part 1 of the interview, click here.

Transcript

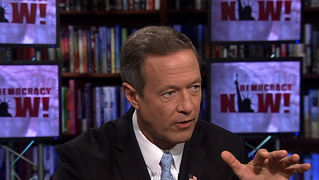

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. Our guest for the hour is Noam Chomsky, the world-renowned political dissident, linguist and author, institute professor emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he taught for more than half a century, his latest book titled Who Rules the World? Noam Chomsky, can you talk about what you think needs to happen in Syria right now?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Syria is spiraling into real disaster, a virtual suicide. And the only sensible approach, the only slim hope, for Syria is efforts to reduce the violence and destruction, to establish small regional ceasefire zones and to move toward some kind of diplomatic settlement. There are steps in that direction. Also, it’s necessary to cut off the flow of arms, as much as possible, to everyone. That means to the vicious and brutal Assad regime, primarily Russia and Iran, to the monstrous ISIS, which has been getting support tacitly through Turkey, through—to the al-Nusra Front, which is hardly different, has just the—the al-Qaeda affiliate, technically broke from it, but actually the al-Qaeda affiliate, which is now planning its own—some sort of emirate, getting arms from our allies, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Our own—the CIA is arming them. We don’t know at what level; it’s clandestine. As much as possible, cut back the flow of arms, the level of violence, try to save people from destruction. There should be far more support going simply for humanitarian aid. Those who are building some sort of a society in Syria—notably, the Kurds—should be supported in that effort.

These efforts should be made to cut off the flow of jihadis from the places where they’re coming from. And that means understanding why it’s happening. It’s not enough just to say, “OK, let’s bomb them to oblivion.” This is happening for reasons. Some of the reasons, unfortunately, are—we can’t reverse. The U.S. invasion of Iraq was a major reason in the development, a primary reason in the incitement of sectarian conflicts, which have now exploded into these monstrosities. That’s water under the bridge, unfortunately, though we can make sure not to do that—not to continue with that. But we may like it or not, but ISIS, the ISIL, whatever you want to call it, does have popular support even among people who hate it. The Sunni—much of the Sunni population of Iraq and Syria evidently regards it as better than the alternative, something which at least defends them from the alternative. From the Western countries, the flow of jihadis is primarily from young people who are—who live in conditions of humiliation, degradation, repression, and want something decent—want some dignity in their lives, want something idealistic. They’re picking the wrong horse, by a large margin, but you can understand what they’re aiming for. And there’s plenty of research and studies—Scott Atran and others have worked on this and have plenty of evidence about it. And those—alleviating and dealing with those real problems can be a way to reduce the level of violence and destruction.

It’s much more dramatic to say, “Let’s carpet bomb them,” or “Let’s bomb them to oblivion,” or “Let’s send in troops.” But that simply makes the situation far worse. Actually, we’ve seen it for 15 years. Just take a look at the so-called war on terror, which George W. Bush declared—actually, redeclared; Reagan had declared it—but redeclared in 2001. At that point, jihadi terrorism was located in a tiny tribal area near the Afghan-Pakistan border. Where is—and since then, we’ve been hitting one or another center of what we call terrorism with a sledgehammer. What’s happened? Each time, it spreads. By now, it’s all over the world. It’s all over Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, everywhere you look. Take the bombing of Libya, which Hillary Clinton was strongly in favor of, one of the leaders of, smashed up Libya, destroyed a functioning society. The bombing sharply escalated the level of atrocities by a large factor, devastated the country, left it in the hands of warring militias, opened the door for ISIS to establish a base, spread jihadis and heavy weapons all through Africa, in fact, into the Middle East. Last year, the—according to U.N. statistics, the worst terror in the world was in West Africa, Boko Haram and others, to a considerable extent an offshoot of the bombing of Libya. That’s what happens when you hit vulnerable systems with a sledgehammer, not knowing what you’re doing and not looking at the roots of where these movements are developing from. So you have to understand the—understand where it’s coming from, where the appeal lies, what the roots are—there are often quite genuine grievances—at the same time try to cut back the level of violence.

And, you know, we’ve had experience where things like this worked. Take, say, IRA terrorism. It was pretty severe. Now, they practically murdered the whole British Cabinet at one point. As long as Britain responded to IRA terrorism with more terror and violence, it simply escalated. As soon as Britain finally began—incidentally, with some helpful U.S. assistance at this point—in paying some attention to the actual grievances of Northern Irish Catholics, as soon as they started with that, violence subsided, reduced. People who had been called leading terrorists showed up on negotiating teams, even, finally, in the government. I happened to be in Belfast in 1993. It was a war zone, literally. I was there again a couple of years ago. It looks like any other city. You can see ethnic antagonisms, but nothing terribly out of the ordinary. That’s the way to deal with these issues.

Incidentally, what’s happening in Syria right now is horrendous, but we shouldn’t—useful to remember that it’s not the first time. If you go back a century, almost exactly a century, the end of the First World War, there were hundreds of thousands of people starving to death in Syria. Proportionally, proportional to the population, it’s likely that more Syrians died in the First World War than any other belligerent. Syria did revive, and it can revive again.

AMY GOODMAN: What about Saudi Arabia, both in the context of Syria, the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia, and how much control Saudi Arabia has over this situation, not to mention what’s happening right now in Yemen, the U.S.-supported Saudi strikes in Yemen? But start with Syria.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, there’s a long history. The basic—we don’t have a lot of time, but the basic story is that the United States, like Britain before it, has tended to support radical Islamism against secular nationalism. That’s been a consistent theme of imperial strategy for a long time. Saudi Arabia is the center of radical Islamic extremism. Patrick Cockburn, one of the best commentators and most knowledgeable commentators, has correctly pointed out that what he calls the Wahhibisation of Sunni Islam, the spread of Saudi extremist Wahhabi doctrine over Sunni Islam, the Sunni world, is one of the real disasters of modern—of the modern era. It’s a source of not only funding for extremist radical Islam and the jihadi outgrowths of it, but also, doctrinally, mosques, clerics and so on, schools, you know, madrassas, where you study just Qur’an, is spreading all over the huge Sunni areas from Saudi influence. And it continues.

Saudi Arabia itself has one of the most grotesque human rights records in the world. The ISIS beheadings, which shock everyone—I think Saudi Arabia is the only country where you have regular beheadings. That’s the least of it. Women have no—can’t drive, so on and so forth. And it is strongly backed by the United States and its allies, Britain and France. Reason? It’s got a lot of oil. It’s got a lot of money. You can sell them a lot of arms, I think tens of billions of dollars of arms. And the actions that it’s carrying out, for example, in Yemen, which you mentioned, are causing an immense humanitarian catastrophe in a pretty poor country, also stimulating jihadi terrorism, naturally, with U.S. and also British arms. French are trying to get into it, as well. This is a very ugly story.

Saudi Arabia—Saudi Arabia itself, its economy—its economy is based not only on a wasting resource, but a resource which is destroying the world. There’s reports now that it’s trying to take some steps to—much belated steps; should have been 50 years ago—to try to diversify the economy. It does have resources that are not destructive, like sunlight, for example, which could be used, and is, to an extent, being used for solar power. But it’s way too late and probably can’t be done. But it’s a—it has been a serious source of major global problems—a horrible society in itself, in many ways—and the U.S. and its allies, and Britain before it, have stimulated these radical Islamist developments throughout the—throughout the Islamic world for a long time.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think Obama has dealt with Saudi Arabia any differently than President Bush before him?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Not in any way that I can see, no. Maybe in nuances.

AMY GOODMAN: What about what’s happening right now in Brazil, where protests are continuing over the Legislature’s vote to suspend President Dilma Rousseff and put her on trial? Now El Salvador has refused to recognize the new Brazilian government. The Brazilian—the Salvadoran president, Cerén, said Rousseff’s ouster had, quote, “the appearance of a coup d’état.” What’s happening there? And what about the difference between—it looked like perhaps Bush saved Latin America simply by not focusing on it, totally wrapped up in Iraq and Afghanistan. It looks like the Obama administration is paying a bit more attention.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, I don’t think it’s just a matter of not paying attention. Latin America has, to a significant extent, liberated itself from foreign—meaning mostly U.S.—domination in the past 10 or 15 years. That’s a dramatic development in world affairs. It’s the first time in 500 years. It’s a big change. So the so-called lack of attention is partly the fact that the U.S. is kind of being driven out of the hemisphere, less that it can do. It used to be able to overthrow governments, carry out coups at will and so on. It tries. There have been three—maybe it depends how you count them—coups, coup attempts this century. One in Venezuela in 2002 succeeded for a couple of days, backed by the U.S., overthrown by popular reaction. A second in Haiti, 2004, succeeded. The U.S. and France—Canada helped—kidnapped the president, sent him off to Central Africa, won’t permit his party to run in elections. That was a successful coup. Honduras, under Obama, there was a military coup, overthrew a reformist president. The United States was almost alone in pretty much legitimizing the coup, you know, claiming that the elections under the coup regime were legitimate. Honduras, always a very poor, repressed society, became a total horror chamber. Huge flow of refugees, we throw them back in the border, back to the violence, which we helped create. Paraguay, there was a kind of a semi-coup. What’s happening—also to get rid of a progressive priest who was running the country briefly.

What’s happening in Brazil now is extremely unfortunate in many ways. First of all, there has been a massive level of corruption. Regrettably, the Workers’ Party, Lula’s party, which had a real opportunity to achieve something extremely significant, and did make some considerable positive changes, nevertheless joined the rest—the traditional elite in just wholesale robbery. And that should—that should be punished. On the other hand, what’s happening now, what you quoted from El Salvador, I think, is pretty accurate. It’s a kind of a soft coup. The elite detested the Workers’ Party and is using this opportunity to get rid of the party that won the elections. They’re not waiting for the elections, which they’d probably lose, but they want to get rid of it, exploiting an economic recession, which is serious, and the massive corruption that’s been exposed. But as even The New York Times pointed out, Dilma Rousseff is maybe the one politician who hasn’t—leading politician who hasn’t stolen in order to benefit herself. She’s being charged with manipulations in the budget, which are pretty standard in many countries, taking from one pocket and putting it into another. Maybe it’s a misdeed of some kind, but certainly doesn’t justify impeachment. In fact, she’s—we have the one leading politician who hasn’t stolen to enrich herself, who’s being impeached by a gang of thieves, who have done so. That does count as a kind of soft coup. I think that’s correct.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to move back to the United States, to the issue of the Republican Party and what you see happening there, the Republican establishment fiercely opposed to the presumptive nominee. I don’t know if we’ve ever seen anything like this, although that could be changing. Can you talk about the significance—I mean, you have Sheldon Adelson, who is now saying he will pour, what, tens of millions of dollars into Donald Trump. You have the Koch brothers—I think it was Charles Koch saying he could possibly see supporting Hillary Clinton, if that were the choice, with Donald Trump. What is happening?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, first of all, the phenomenon that we’ve just seen is an extreme version of something that’s been going on just for years in the Republican primaries. Take a look back at the preceding ones. Every time a candidate came up from the base—Bachmann, McCain, Santorum, Huckabee, one crazier than the other—every time one rose from the base, the Republican establishment sought to beat them down and get their own—get their own man—you know, Romney. And they succeeded, until this year. This year the same thing happened, and they didn’t succeed. The pressure from the base was too great for them to beat it back. Now, that’s the disaster that the Republican establishment sees. But the phenomenon goes way back. And it has roots. It’s kind of like jihadis: You have to ask about the roots.

What are the roots? The Republican—both political parties have shifted to the right during the neoliberal period—the period, you know, since Reagan, goes back to late Carter, escalated under Reagan—during this period, which has been a period of stagnation and decline for much of the population in many ways—wages, benefits, security and so on—along with enormous wealth concentrated in a tiny fraction of the population, mostly financial institutions, which are—have a dubious, if not harmful, role on the economy. This has been going on for a generation. And while this has been happening, there’s a kind of a vicious cycle. You have more concentration of wealth, concentration of political power, legislation to increase concentration of wealth and power, and so on, that while that’s been going on, much of the population has simply been cast aside. The white working class is bitter and angry, for lots of reasons, including these. The minority populations were hit very hard by the Clinton destruction of the welfare system and the incarceration rules. They still tend to support the Democrats, but tepidly, because the alternative is worse, and they’re taking a kind of pragmatic stand.

But while the parties have shifted to—but the parties have shifted so far to the right that the—today’s mainstream Democrats are pretty much what used to be called moderate Republicans. Now, the Republicans are just off the spectrum. They have been correctly described by leading conservative commentators, like Norman Ornstein and Thomas Mann, as just what they call a radical insurgency, which has abandoned parliamentary politics. And they don’t even try to conceal it. Like as soon as Obama was elected, Mitch McConnell said, pretty much straight out, “We have only one policy: make the country ungovernable, and then maybe we can somehow get power again.” That’s just off the spectrum.

Now, the actual policies of the Republicans, whether it’s Paul Ryan or Donald Trump, to the extent that he’s coherent, Ted Cruz, you pick him, or the establishment, is basically enrich and empower the very rich and the very powerful and the corporate sector. You cannot get votes that way. So therefore the Republicans have been compelled to turn to sectors of the population that can be mobilized and organized on other grounds, kind of trying to put to the side the actual policies, hoping, the establishment hopes, that the white working class will be mobilized to vote for their bitter class enemies, who want to shaft them in every way, by appealing to something else, like so-called social conservatism—you know, abortion rights, racism, nationalism and so on. And to some extent, that’s happened. That’s the kind of thing that Fritz Stern was referring to in the article that I mentioned about Germany’s collapse, this descent into barbarism. So what you have is a voting base consisting of evangelical Christians, ultranationalists, racists, disaffected, angry, white working-class sectors that have been hit very hard, that are—you know, not by Third World standards, but by First World standards, we even have the remarkable phenomenon of an increase in mortality among these sectors, that just doesn’t happen in developed societies. All of that is a voting base. It does produce candidates who terrify the corporate, wealthy, elite establishment. In the past, they’ve been able to beat them down. This time they aren’t doing it. And that’s what’s happening to the so-called Republican Party.

We should recognize—if we were honest, we would say something that sounds utterly shocking and no doubt will be taken out of context and lead to hysteria on the part of the usual suspects, but the fact of the matter is that today’s Republican Party qualify as candidates for the most dangerous organization in human history. Literally. Just take their position on the two major issues that face us: climate change, nuclear war. On climate change, it’s not even debatable. They’re saying, “Let’s race to the precipice. Let’s make sure that our grandchildren have the worst possible life.” On nuclear war, they’re calling for increased militarization. It’s already way too high, more than half the discretionary budget. “Let’s shoot it up.” They cut back other resources by cutting back taxes on the rich, so there’s nothing left. There’s been nothing this—literally, this dangerous, if you think about it, to the species, really, ever. We should face that.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think that President Obama has intensified this threat, I mean, now with the trillion-dollar plan to, quote, “modernize” the nuclear arsenal?

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s a very bad step. And it’s not just modernizing the arsenal, which ought to be reduced. Worth remembering we have even a legal obligation to cut back and, ultimately, eliminate nuclear weapons. But it’s also something you mentioned earlier: developing these small nuclear weapons. Sounds kind of nice. They’re small, not big. It’s the opposite. Small nuclear weapons provide a temptation to use them, figuring, “Well, it’s only a small weapon, so it won’t destroy, you know, a whole city.” But as soon as you use a small nuclear weapon, chances of retaliation escalate pretty sharply. And that means you could pretty soon be in a situation where you’re having a real nuclear exchange, pretty well known now that that would lead to a nuclear winter, which would make life essentially impossible.

AMY GOODMAN: As President Obama heads to Hiroshima, do you think he should be apologizing for the only nuclear bombs, atomic bombs, dropped in the world, the U.S. dropping them, launching the nuclear age, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in ’45?

NOAM CHOMSKY: I thought—I mean, I’m old enough to remember it. And that day was just the—maybe the grimmest day I can remember. Then came something even worse: the bombing of Nagasaki, mainly to try to test a new weapon design. These are real horror stories. The carpet—the bombing, firebombing of Japanese cities a couple months earlier was not that much better, Tokyo especially. We might even recall that there was what was called a grand finale in the Air Force history. After the two atom bombs, after Russia had entered the war, which ended any Japanese hope for any kind of—any hope that they had for any sort of negotiated settlement, after that—it was all over—after Japan had officially surrendered, though before it had been made public, after that, the U.S. organized a thousand-plane raid, which was a big logistic feat, to bomb Japanese cities to kind of show the “Japs” who was on top, and survivors, so like Makoto Oda, a well-known Japanese writer who recently died, reported that as a child in Osaka, he remembers bombs falling along with leaflets saying, “Japan has surrendered.” Now, that was not a lethal bombing, but it was a brutal one, a brutal sign of brutality. All of these events call for serious rethinking—yes, apology, but mainly serious rethinking of just what we’re up to in the world.

And remember that this goes on. Those were small bombs by today’s standard. If you look at the record since, since 1945, it’s an absolute miracle that we’ve survived. New examples are discovered all the time. Just a couple of months ago, it was revealed that in 1979, last Carter year, the U.S. automated detection systems sent a—determined that there was a major Russian missile attack against the United States. Protocol is, this goes to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, they evaluate it, goes to the national security adviser—Zbigniew Brzezinski at the time—and he notifies the president. Brzezinski was actually on the phone, ready to call Carter to launch a nuclear attack, which means the Doomsday Clock goes to midnight, on the phone when they received information saying that it was a false alarm, another of the hundreds, if not thousands, of false alarms. On the Russian side, there are probably many more, because their equipment is much worse. These things happen constantly. And to play games with escalating the nuclear arsenal, when it should be reduced, sharply reduced—I mean, even people like Henry Kissinger, George Shultz and so on, are calling for elimination of nuclear weapons. To escalate and modernize at this point is just really criminal, in my opinion.

AMY GOODMAN: What is your overall assessment of the Obama administration?

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s about what I thought before he—before the 2008 primaries, when I wrote about him just based on the information in his web page. I didn’t expect anything. I expected mostly rhetoric and—you know, nice rhetoric, good speaker and so on, but nothing much in the way of action. I don’t usually agree with Sarah Palin, but when she was ridiculing this—what she called this “hopey-changey stuff,” she had a point. There were a few good things. You know, there were a few good things in the W. Bush administration. But opportunities that were available, especially in the first two years when he had Congress with him, just were not used. And some—it’s—by the standards of U.S. presidential politics, it’s kind of nothing special either way, nothing to rave about, certainly.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about the passing of Michael Ratner, Michael Ratner, the former head of the—or the late head of the Center for Constitutional Rights, the trailblazing human rights attorney, who died last week at the age of 72. I had interviewed Michael last year in Washington, D.C., at the reopening of the Cuban Embassy, after it was closed for more than five decades. And I asked Michael to talk about the significance of this historic day. This is an excerpt of what he said.

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, Amy, let’s just say, other than the birth of my children, this is perhaps one of the most exciting days of my life. I mean, I’ve been working on Cuba since the early ’70s, if not before. I worked on the Venceremos Brigade. I went on brigades. I did construction. And to see that this can actually happen in a country that decided early on that, unlike most countries in the world, it was going to level the playing field for everyone—no more rich, no more poor, everyone the same, education for everyone, schooling for everyone, housing if they could—and to see the relentless United States go against it, from the Bay of Pigs to utter subversion on and on, and to see Cuba emerge victorious—and when I say that, this is not a defeated country. This is a country—if you heard the foreign minister today, what he spoke of was the history of U.S. imperialism against Cuba, from the intervention in the Spanish-American War to the Platt Amendment, which made U.S. a permanent part of the Cuban government, to the taking of Guantánamo, to the failure to recognize it in 1959, to the cutting off of relations in 1961. This is a major, major victory for the Cuban people, and that should be understood. We are standing at a moment that I never expected to see in our history.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Michael Ratner. It was July [20th]. It was that historic day in Washington, D.C., when the Cuban Embassy was opened after almost half a century. If you could talk both about the significance of Michael Ratner, from his work around Guantánamo, ultimately challenging the habeas corpus rights of Guantánamo prisoners, that they should have their day in court, and winning this case in the Supreme Court, to all of his work, also talk about Cuba, Noam, something that you certainly take on in your new book, Who Rules the World?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, Michael Ratner has an absolutely fabulous record. His achievements have been enormous. A tremendous courage, intelligence, dedication. A lot of achievement against huge odds. The center, which he largely—it was a major—he ran and was a major actor in, has done wonderful work all over the place—Cuba and lots of other things. So I can’t be excessive in my praise for what he achieved in his life and the inspiration that it should leave us with.

With regard to Cuba-U.S. relations, I think what he just said is essentially accurate. In fact, it’s even worse than that. We tend to forget that after the Bay of Pigs, the Kennedy administration was practically in a state of hysteria and seeking to somehow avenge themselves against this upstart who was carrying out what the government called successful defiance of U.S. policies going back to the Monroe Doctrine. How can we tolerate that? Kennedy authorized a major terrorist war against Cuba. The goal was to bring “the terrors of the earth” to Cuba. That’s the phrase of his associate Arthur Schlesinger, historian Arthur Schlesinger, in his biography of Robert Kennedy. Robert Kennedy was given the responsibility to bring “the terrors of the earth” to Cuba. And it was—he in fact described it as one of the prime goals of government, is to ensure that we terrorize Cuba. And it was pretty serious. Thousands of people were killed, petrochemical plants, other industrial installations blown up. Russian ships in the Havana Harbor were attacked. You can imagine what would happen if American ships were attacked. It was probably connected with poisoning of crops and livestock, can’t be certain. It went on into the 1990s, though not at that—not at the extreme level of the Kennedy years, but pretty bad. The late ’70s, there was an upsurge, blowing up of a Cubana airliner, 73 people killed. The culprits are living happily in Miami. One of them died. The other, Luis Posada, major terrorist, is cheerfully living there.

The taking over of southeastern Cuba back—at the time of the Platt Amendment, the U.S. had absolutely no claim to this territory, none whatsoever. We’re holding onto it just in order—it’s a major U.S. military base—it was. But we’re holding onto it simply to impede the development of Cuba, a major port, and to have a dumping place where we can send—illegally send Haitian refugees, claiming that they’re economic refugees, when they’re fleeing from the terror of the Haitian junta that we supported—Clinton, incidentally, in this case—or just as a torture chamber. Now, there’s a lot of talk about human rights violations in Cuba. Yeah, there are human rights violations in Cuba. By far the worst of them, overwhelmingly, are in the part of Cuba that we illegally hold—you know, technically, legally. We took it at the force of a gun, so it’s—point of a gun, so it’s legal. I mean, in comparison with this, whatever you think of Putin’s annexation of Crimea is minor in comparison with this.

All of this is correct, but we have to ask: Why did the U.S. decide to normalize relations with Cuba? The way it’s presented here, it was a historic act of magnanimity by the Obama administration. As he, himself, put it, and commentators echoed, “We have tried for 50 years to bring democracy and freedom to Cuba. The methods we used didn’t work, so we’ll try another method.” Reality? No, we tried for 50 years to bring terror, violence and destruction to Cuba, not just the terrorist war, but the crushing embargo. When the Russians disappeared from the scene, instead of—you know, the pretense was, “Well, it’s because of the Russians.” When they disappeared from the scene, how did we react, under Clinton? By making the embargo harsher. Clinton outflanked George H.W. Bush from the right, in harsh—during the electoral campaign, in harshness against Cuba. It was Torricelli, New Jersey Democrat, who initiated the legislation. Later became worse with Helms-Burton. All of this has been—that’s how we tried to bring democracy and freedom to Cuba.

Why the change? Because the United States was being driven out of the hemisphere. You take a look at the hemispheric meetings, which are symbol of it. Latin America used to be just the backyard. They do what you tell them. If they don’t do it, we throw them out and put in someone else. No more. Not in the last 10, 20 years. There was a hemispheric meeting in Cartagena, in Colombia. I think it was—must have been 2012, when the U.S. was isolated. U.S. and Canada were completely isolated from the rest of the hemisphere on two issues. One was admission of Cuba into hemispheric systems. The second was the drug war, which Latin America are essentially the victims of the drug war. The demand is here. Actually, even the supply of weapons into Mexico is largely here. But they’re the ones who suffer from it. They want to change it. They want to move in various ways towards decriminalization, other measures. U.S. opposed. Canada opposed. It was pretty clear at that time that at the next hemispheric meeting, which was going to be in Panama, if the U.S. still maintained its position on these two issues, the hemisphere would just go along without the United States. Now, there already are hemispheric institutions, like CELAC, UNASUR for South America, which exclude the United States, and it would just move in that direction. So, Obama bowed to the pressure of reality and agreed to make—to accept the demand to—the overwhelming demand to move slowly towards normalization of relations with Cuba. Not a magnanimous gesture of courage to bring Cuba—to protect Cuba from its isolation, to save them from their isolation; quite the opposite, to save the United States from its isolation. Of course, with the rest of the world, there’s not even any question. Take a look at the annual votes on—the U.N. has annual votes on the U.S. embargo, and just overwhelming. I think the last one was something like 180 to two—United States and Israel. It’s been increasing like that for years. So, that’s the background.

As for Michael, Michael Ratner, his achievements are just really spectacular.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Noam, you’ve just written this book, Who Rules the World? You’ve written more than a hundred other books. And, I mean, you have been a deep, profound thinker and activist on world issues, for what? I mean, more than 70 years. You were writing when you were 14 years old, giving your analysis of what’s been happening. And I’m wondering where you think we stand today, if you agree with—well, with Dr. Martin Luther King, that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Actually, it was 10 years old, but not—nothing to rave about. If you look over the past, say, the roughly 75 years of my, more or less, consciousness, it’s—in general, I think the arc of history has been bending towards justice. There have been many improvements, some of them pretty dramatic—women’s rights, for example, to an extent, civil rights. It should be remembered that there were literally lynchings in the South until the early 1950s. It’s not beautiful now, but that’s not happening. There have been steps forward. Opposition to aggression is much higher than it was in the past. There’s finally concern for environmental issues, which are really of desperate necessity. All of this is slow, halting, significant steps bending the arc of history in the right way.

There’s been regression, a lot of regression. Things don’t move smoothly. But there have been bad periods before, and we’ve pulled out of them. I think there are opportunities—they’re not huge, but they’re real—to overcome the—and I stress again—to overcome problems that the human species has never faced in its roughly 200,000 years of existence, problems of, literally, survival. We’ve already answered these questions for a huge number of species: We’ve killed them off.

AMY GOODMAN: Noam Chomsky, world-renowned political dissident, linguist and author, institute professor emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he’s taught for more than 50 years. His latest book is Who Rules the World? This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options