Guests

- Seth Freed Wesslerfilmmaker and investigative reporter for ProPublica.

- Nilson Barahona-Marriagaimmigration rights activist with The ICE Breakers.

We go inside a notorious ICE jail at the height of the pandemic to see how people held there spoke out against dangerous conditions and faced retaliation, before they were ultimately released with no notice. Their story is captured in a new documentary called “The Facility.” It investigates the inhumane conditions at Irwin County Detention Center using footage from video calls, where cameras installed in cell blocks to enable pay-per-minute video calls “functioned almost like a portal for a moment in and out of a place meant not to be seen in this way,” says director Seth Freed Wessler. “How can your own government be doing this to you?” asks Nilson Barahona-Marriaga, one of the people featured in interviews with Wessler in the eye-opening footage from inside the jail.

Transcript

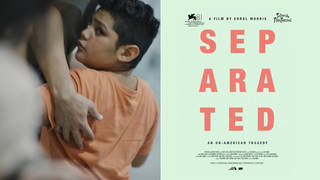

AMY GOODMAN: As we continue on the issue of how the U.S. deals with immigration, this is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. The network of ICE jails across the United States is vast, as we turn from New Mexico to Georgia, where immigrants held at the Irwin County Detention Center were held in solitary confinement after they protested their conditions during the first months of the coronavirus pandemic, their fight the focus of a new documentary called The Facility. This is the trailer.

NILSON’S ATTORNEY: We’re asking for these petitioners to be released.

JUDGE CLAY D. LAND: I’ve already — I’ve already ruled on that. And I haven’t heard anything to change my mind.

SETH FREED WESSLER: How’s everybody doing? What’s happening here?

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Somebody here tested positive for coronavirus.

DETAINEE: I’m really scared I’m going to die.

REYDEL: [translated] This is what we came up with to try to protect ourselves.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: The women, they’re going to go on strike.

NEWS ANCHOR: [translated] Detained immigrant women are in utter despair.

DETAINEE: [translated] We are recording this video in fear.

ANDREA MANRIQUE: [translated] I have to speak out.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: [translated] They’re saying, “Abolish ICE.”

REP. JOAQUIN CASTRO: She described the experience here as torture.

ANDREA MANRIQUE: [translated] They hit me. Can you see?

SETH FREED WESSLER: Can you — can you just keep it running?

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: You think we all fit in the hole? They can’t put us all in the hole.

SETH FREED WESSLER: [translated] What have you heard?

ANDREA’S PARTNER: They isolated them all.

GUARD: The facility is going to continue addressing issues as they arise. What that entails, I have no idea.

AMY GOODMAN: The Facility is directed by journalist Seth Freed Wessler, who began investigating the story last year. This was six months before a whistleblower, a nurse working at the Irwin ICE jail, said women held there were being subjected to forced sterilization. At the start of the pandemic, Seth connected with people inside the jail by talking to them through video calls that he recorded. This is a clip.

SETH FREED WESSLER: How’s everybody doing? How are you thinking about what’s happening out here, this coronavirus thing?

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Everybody is here under a lot of stress. We see what’s happening outside and how fast it’s been moving. Once it gets in here, we’re all at great risk.

ANDREA MANRIQUE: [translated] Our safety here is not up to us. It’s up to third parties, and these third parties lie to us.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: The guards, they only wear their face mask on Monday and allow them — they don’t even have it on, at all. As we see, there’s one up there. There’s one up there checking through the rooms.

JUBRIL: They are not practicing it, which is the social distance, the six feet. With 32 people in here, there’s no way we are going to practice that.

YANET: [translated] I made this myself with a sock to cover my face, because I refuse to run the risk.

AMY GOODMAN: In that clip, you hear Seth Freed Wessler talking to Andrea Manrique and Nilson Barahona. In a minute, Seth and Nilson will join us. But first, this is one more clip from The Facility, where Seth is talking to Nilson just as a guard comes in, and Nilson confronts him. Listen carefully.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Can you call me after the break?

SETH FREED WESSLER: Can you — can you just keep it running?

GUARD: There is nobody infected in this facility.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: OK, let me tell you something. My name is Nilson Barahona. I put a lawsuit, OK, to this facility. Both of the wardens were in a federal court on Thursday, and they declared that they have tested three people, and one came positive.

GUARD: The people responsible are nowhere to be found. They are all sitting at home somewhere barking orders, telling people like me what to say to you. It’s a [bleep]-up situation. It really is. The facility is going to continue addressing issues as they arise. What that entails, I have no idea.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, for more, we’re joined by Nilson Barahona, one of the two people featured in The Facility. Originally from Honduras, he has lived in the United States since 1999, since been released from Irwin, helped found the group called ICE Breakers. Also with us, Seth Freed Wessler, who was a longtime reporting fellow with Type Investigations when he directed this new documentary, produced by Field of Vision, based in part on his reporting for The New York Times Magazine and HuffPost, now a reporter with ProPublica.

Seth, this film is about to come out on MSNBC, I believe. Can you talk about how you did these remarkable videos? And then we’ll talk with Nilson about being at the other end.

SETH FREED WESSLER: Yeah. You know, when the pandemic really began to sort of turn the world upside down, I, as a reporter, decided I wanted to try to connect with people inside of the detention centers, the ICE detention centers, that I had already been reporting on. I had reported on ICE for many years. And so I began to make calls using this pay-per-minute video visitation app that’s installed in cell blocks in many detention centers around the country. I knew about the app already because I had used it to talk to people before the pandemic as I was reporting on ICE. And so I began to make calls to people detained inside of the Irwin County Detention Center to try to figure out what was happening as the pandemic was spreading in this very tightly packed place, and did report a series of stories for the web and for The New York Times Magazine about conditions of confinement, about the failure of ICE and private detention operators to protect people from the spreading virus.

But it struck me very early that what I was seeing through these cameras, that are attached to tablets inside of the cell blocks, really, I couldn’t communicate what I was seeing through print reporting, that this needed to be a story that people could experience visually. And so I embarked on this film project to pull together what ultimately was hundreds of hours of footage that included conversations, interviews with Nilson and Andrea Manrique and many other people held in Irwin, but also at times just footage of life happening inside. I would sometimes spend many hours a day calling and calling, and then people on the inside, including Nilson, would pick up my calls. And at times, I’d ask him — we just saw a clip of this — if we could just keep the camera running, and I would keep recording the footage.

And over time, that practice of just being sort of digitally present made it possible to be present for real things happening inside, events like the one you just saw, and also just sort of to get a sense of the routine daily life inside of this detention center. So, The Facility, which will come out on MSNBC on Sunday night at 10 p.m. but is also now available at Field of Vision’s website, tells the story of a group of people inside of the Irwin County Detention Center trying to raise their voices to hold the Irwin County Detention Center accountable, but also, I hope, can bring people who see it, in a sense, inside.

And in a sense, for me, and, I think, for Nilson and others I talked to, this camera, not so unlike what we’re doing right now, between the detention center streaming onto my computer screen and then streaming back into these tablets inside of the facility, functioned almost like a portal for a moment in and out of a place meant not to be seen in this way.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it is just an astounding documentary with this firsthand video footage. Even when you’re not talking directly to someone, as you point out, you say, “Leave the camera on,” and you hear the guards talking, who admit they have no idea what’s going on. Nilson Barahona, you were there at the other end, and we feel you in this documentary, the fear and trying to get an honest answer about if people have COVID at the height of the pandemic and how you can protect yourself. Can you talk about that fear and what they did at Irwin? Now you’re out, probably because of, among other things, your resistance and the nurse who came forward and talked about the abominable conditions and the fact that women were being sterilized against their will there.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Yeah, it was definitely a very frightening time. You know, in order for me to fight this fight — and I have said this many times — I had to block my emotions, because what we was living in at the time, it was overwhelming, you know? And it was easy to freeze and not to do anything. But I’m a man of faith, and I give thanks to God that I was able to connect with Seth and Diego Sánchez and Lorilei, you know, my lawyers at that time. They were a great help. They were shining the lamp every step I take, you know? And I’m grateful that this documentary came out, because there is no words that can explain what we went through at that time.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what it meant to demand answers about how you could be protected during COVID. I mean, you see Andrea, the other woman in detention, who gets punished for resisting and going on hunger strike, and the agony she goes through in this facility for almost two years. You were on hunger strike, as well, Nilson.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Yeah, it was a decision that it wasn’t really easy to make, you know? And also the fact that we were all able to do this together as a family, I would say. There is no other way to say it, because we knew that all we had was next to us, you know? Everything that we have that we can use to fight, it was next to us, and it was each other. That was basically it. So we’ve got to come together, and we’ve got to raise our voice in order to get the attention that we needed to get to solve that problem.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, when you describe, as you’re talking to Seth on this video call, about your son and what he said to you as you spoke to him in Spanish — you’re inside, he’s out. You’re married. He’s an American citizen. He’s a tiny boy. But the little bond that you had and what you felt was being disrupted?

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: It’s still hard to this point to think about it. Thanks God, you know, I’m able to say right now that that bond is stronger than ever. My boy, he’s 7 years old at this time, but his courage and his character is so strong, and I’m proud of him, you know? But the truth is that it should have never happened, you know. I should have never been taken away from him. He was 5 years old at the time when I got detained. And, you know, during the time, as the months went by and I tried to keep that relationship going, but we were limited, you know, in the kind of communication that we could have. And since he was born, I only speak Spanish to him, so this is our thing, you know? My wife is a United States citizen. She’s from Connecticut. And so, she speaks a little Spanish, but not much. So I’ve tried to make sure that he knows his background, you know, where he’s coming from, and our culture and all that. And I felt like I was losing that with him. And he was — I felt so impotent, you know? There was nothing I could do at that time.

But what hurt me is the fact that: How come your own government can be doing this to you? Like, my wife went through so much. Like, she was — when I came out, she was financially, emotionally, physically drained because all the things that we were supposed to do and take care as a couple, she will have to do it on her own. And not only that, but now she had an extra care of having her husband in detention.

AMY GOODMAN: And as you ask, and as Andrea asks, when you’re just released, after — how long were you in Irwin?

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: Thirteen months. In Irwin —

AMY GOODMAN: Thirteen months. And she, two years.

NILSON BARAHONA-MARRIAGA: In Irwin — I was in Irwin for like seven months, and then, after the hunger strike, I was moved to Stewart Detention Center, which was not better at all.

AMY GOODMAN: You were moved to Stewart. And saying, why couldn’t you be at home as you went through the process? Andrea, they’re breaking her. And in these last few seconds, Seth, the agony we watch Andrea, who had been put in the hole, who had gone on hunger strike, saying, after they released her, why couldn’t she have been waiting for her court date all this time from home?

SETH FREED WESSLER: You know, ICE detention is, in many ways, unique in the complex of ways that we lock people up in the United States, in that it is routinely the case that people don’t know how long they will be held. They don’t know when they will be released. People can be held for many months, and sometimes multiple —

AMY GOODMAN: We have 10 seconds.

SETH FREED WESSLER: — multiple years. And this is a detention system that is at the discretion of ICE. ICE can decide to hold people or not. Everybody who’s in ICE detention could be released and allowed to be home with their families, and that’s a decision that the government makes every day about thousands of people.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there, but you can see the documentary The Facility at MSNBC and Field of Vision. Seth Freed Wessler and Nilson Barahona, thank you. I’m Amy Goodman. Stay safe.

Media Options